(Nairobi) – The Sudanese government’s persistent indiscriminate air attacks in the Nuba Mountains area of Southern Kordofan are killing and maiming children. An aid blockade is causing a health and education crisis in the conflict-affected region.

In April 2015, Human Rights Watch visited 13 villages and towns in rebel-held areas of Southern Kordofan’s Nuba Mountains that had been repeatedly hit by air-dropped bombs and ground shelling in the past year. The researchers focused on how abuses committed during the conflict are especially affecting children.

“Children are literally being blown to pieces by bombs and burned alive with their siblings,” said Daniel Bekele, Africa director at Human Rights Watch. “They are unable to get sufficient food, basic health care, or education, and the situation is only getting worse.”

The Sudanese government’s unlawful attacks on civilians and blocking of essential aid should be investigated as war crimes, Human Rights Watch said. The United Nations Security Council should verify the facts and establish an arms embargo over the conflict zone. The council should also impose travel bans and asset freezes against individuals from both parties to the conflict most responsible for failing to facilitate aid delivery.

Fighting between Sudanese government forces and the armed opposition, the Sudan People’s Liberation Army-North (SPLA-N), began in June 2011 following disputed elections in Southern Kordofan, and quickly spread to Blue Nile state. In both states, the conflict has been marked by Sudan’s use of explosive weapons in air attacks on towns and villages, and dire conditions aggravated by the government’s aid blockade.

Human Rights Watch documented more than 100 civilian casualties in 2014 and 2015 from aerial bombardment or after the initial attack by unexploded ordnance and other explosive remnants of war, including 26 deaths of children and 29 cases in which children were injured, some seriously. In one incident five children were burned to death after a bomb set their house on fire, including one girl with burns all over her body who died weeks later in excruciating pain.

“My neighbors were holding me back from where my children had been bombed – some of the body parts were in this tree,” a woman who lost six children in a bombing in 2014 told researchers as she sat next to her destroyed house in Heiban town, Heiban county.

A local organization of Sudanese human rights monitors has documented numerous additional instances of bombing, shelling, and civilian casualties during this period.

Human Rights Watch also found evidence that government aircraft deliberately bombed hospitals and other humanitarian facilities. In May and June 2014, several hospitals and other humanitarian facilities were bombed within a short time period, preceded in three cases by drones flying over the facilities, suggesting deliberate targeting.

The attacks on health facilities and the wider pattern of indiscriminate bombardment of towns and villages, often hitting homes, farms, and health and education facilities, constitute war crimes, Human Rights Watch said. The attacks have further eroded health services that were already devastated by four years of conflict and the government’s policy of blocking international aid agencies from working in rebel-held areas, put in place soon after the conflict began. The parties to the conflict have since failed to agree on how aid can be delivered, including food, medicine, and school supplies.

The deliberate denial of humanitarian aid is a violation of international law and could also amount to a war crime, Human Rights Watch said.

The majority of children born in the rebel-held Nuba Mountains region since 2011 have not been vaccinated against preventable diseases. After the parties failed to agree to a temporary ceasefire for an emergency polio vaccination campaign in 2013, a measles outbreak infected many hundreds and perhaps thousands of children.

Local health workers received almost 2,000 suspected measles cases between April and December 2014. While health workers have managed to vaccinate tens of thousands of children against this disease, many thousands are still at risk. New cases are still being reported. If an agreement is reached for the UN polio vaccination campaign, it could also include vaccinating against measles in outbreak areas, Human Rights Watch said.

“The two sides have an obligation under international law to minimize harm to civilians and not to block access to independent health care services,” Bekele said. “They should urgently facilitate vaccinations before the coming rains reduce access or risk further outbreaks.”

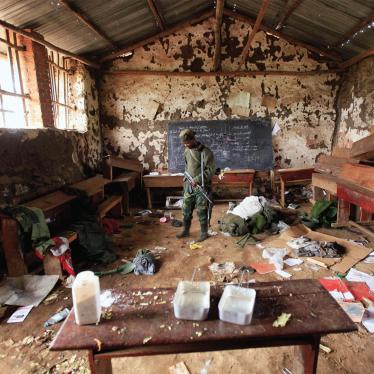

The conflict and aid blockade have also eviscerated the education system, Human Rights Watch found. Government bombing has damaged or destroyed more than 20 schools, and most of the remaining 250 schools are operating outdoors under trees or nestled in rocky hills to protect them. Most have no school supplies, in some places forcing children to learn, and even complete their exams, orally and by writing words in the sand.

“Four years on, the impact of these dire conditions in the Nuba Mountains is all too clear,” Bekele said. “International pressure on the parties to agree on aid access hasn’t worked. The Security Council should follow through on threats to impose sanctions on those responsible for blocking aid, and establish an arms embargo.”

For details of the bombing campaign, please see below.

The Bombing Campaign

Since 2011, the Sudanese government has persistently used air-dropped bombs on civilian areas of Southern Kordofan delivered by Antonov cargo planes flying at high altitudes or by lower-flying jets.

The types of bombs dropped are not well-documented, but Human Rights Watch researchers found a unitary explosive bomb with a parachute attached at the site of an air attack on the town of Kauda, in Heiban county, in May 2014. It is most likely Western-made, and from Sudan’s older stockpiles.

Human Rights Watch also found evidence that Sudan probably used cluster bombs in Southern Kordofan, and observed the remnants of the bombs in the villages of Tungoli and Rajeefi in April 2015. These weapons are banned by the Convention on Cluster Munitions, which Sudan has not joined.

Human Rights Watch opposes the use of air-dropped bombs and other explosive weapons with wide-area effect in populated areas as being inevitably indiscriminate – that is, unable to discriminate between civilians and military targets. When explosive weapons such as these detonate, they emit a destructive blast wave and metal fragments that have a long and lethal reach. The metal casing of the explosive weapon may also be designed to shatter into uniform, pre-formed fragments, which can penetrate the body and rip internal organs.

Children Killed by Explosive Weapons Used in Populated Areas

Human Rights Watch documented a series of incidents in 2014 and the first three months of 2015 in which aerial bombardment or shelling killed children. In some cases, children were killed while hiding in foxholes.

In mid-February 2015, five children ranging from about 4 to 17 burned to death after a bomb dropped by an Antonov aircraft landed on a house in Seraf Jamous, in Um Durein county, and set it on fire. The children were in school when they heard a plane and fled to the house to hide in an adjacent animal pen, where they were trapped after the bomb dropped, a teacher who saw the fire told Human Rights Watch.

A sixth child, a girl hiding with rest of the group, was completely burned except for a small area on her stomach and died several weeks later. A doctor who treated the girl said she had never seen a human being in so much pain. Two other children and an adult were injured.

In early February 2015, in Um Sirdiba, a young child and an 18-year-old woman were killed immediately when a shell landed on the compound where they were sleeping. Fire caused by the same shell killed four of seven children trapped in a foxhole where they had hidden for safety.

One child was burned so completely a local chief described her as “completely black and dry,” while six others were rescued just before another shell landed on the property, according to a local leader who helped put the fire out. Because of a lack of transport, it took almost two days to get the six children to a hospital, where three of them later died from their burns, witnesses and medical staff said.

In March 2015, a boy and two girls were killed as they sought shelter under a tree when a shell landed close to them in the Um Sirdiba area of Um Durein county. The shell was fired from the direction of Kadugli, the government-controlled state capital.

Because of the frequent shelling in Um Sirdiba, about 270 families have sought shelter in a stony valley in the Al Nugra area, but have experienced air attacks there, too. On January 22, a very small girl and her 14-year-old brother were killed when a bomb dropped by an aircraft landed next to their shelter.

In January, a 4-year-old boy died on his way to the hospital, wounded when aircraft dropped more than 20 bombs on the village of Abu Leila in Buram county.

In February 2014, a child was among 13 people killed when a jet aircraft dropped more than 20 bombs on a small market and surrounding areas next to a gold mining area in the Um Dullu area, also in Buram county. According to local human rights monitors, 16 other people were injured in the incident.

On October 16, 2014, six children were killed and one injured when a house was bombed by an Antonov airplane in Heiban town, Heiban county. The plane flew over the town in the morning dropping at least eight bombs on the settlement, also killing a man, witnesses said. The children’s mother described rushing back to the house after the attack and being held back by neighbors who had arrived before her, to prevent her from seeing her children’s body parts, some hanging in a tree.

Human Rights Watch also found that bombing causing death and injury has continued on settlements in and around Heiban county. In February 2015, an air-dropped bomb killed a woman, and an air attack on March 14 injured nine people, witnesses said.

In February, an 8-year-old child and his grandmother died when a bomb dropped by an Antonov aircraft landed on their house in the small town of Kalkada, in Heiban county, in what local chiefs described as one of many attacks during February and March.

On the evening of January 31, two aircraft dropped about 20 bombs on the village of Nyakama in Heiban county, killing a woman and a child and injuring three other children, according to local human rights monitors. Earlier that month, in the same village, another attack killed five adults.

In May 2014, a bomb killed three teenage girls who were sleeping, for safety, near caves in Tongoli village, Delami county. The blast tore one girl’s body in half, while shell fragments cut her sisters’ bodies “in many places,” relatives who were there said.

When Human Rights Watch visited Tongoli in April 2015, researchers found that shelling from Sudanese government forces shooting from a front line an estimated 30 kilometers away had injured four more children.

Also in Delami county, two small children were killed in the village of Kereli, near Tongoli village, when a bomb landed near the foxhole where they were hiding. The children’s elder brother, who survived, said his siblings had died from the heat and smoke.

Human Rights Watch found that four other children had since been injured in Kereli by air attacks during 2015 that also resulted in the burning of many huts.

Children Injured by Explosive Weapons Used in Populated Areas

Human Rights Watch also documented numerous other cases in which children were injured from the use of explosive weapons in civilian populated areas.

A 10-year-old girl, still recovering in a hospital, told researchers that in mid-February 2015 she and her friend were injured by a bomb dropped near a water collection point in Showri village, Heiban county. “I can’t remember it well but discovered that my left leg was cut off,” she said.

Around the same time, another girl, 12-years-old, lost her lower leg after she was hit by fragments from a bomb dropped by what witnesses said was an Antonov aircraft on Alabu village in Um Dorein county.

On February 1, 2015, two bombs dropped by an Antonov aircraft fell near their home in Rajeefi village, Um Dorein county, injuring five children, family members said. The father of two of the children said he had to carry two of his children, one of whom had 20 to 30 fragments of metal in his body, many kilometers to try and find a car to take them to hospital.

In early March 2015, three children were injured by a bomb dropped by what witnesses said was an Antonov aircraft on Dabi town, also in Um Dorein, where three adults were killed in April 2014 in a bombing. Explosive remnants of war have also harmed children, Human Rights Watch found. Two boys from Mendi, in Heiban county, ages 12 and 13, were badly injured by explosive objects they found on the ground in separate incidents at separate locations, both while searching for mangoes.

One was injured all over his body. His stepmother said that the boy had found a bell-shaped object with what looked like a blade inside: “He was trying to break open [the bomb] to use it to make a knife to eat mangoes.” The other boy’s face was seriously injured when he threw an object he found against a rock to try to crack it open. He was also searching for a knife to cut mangoes, his brother said.

Air Attacks on Health Facilities

Local health officials provided Human Rights Watch with a list of 22 health facilities damaged since 2011, mostly by the government’s air attacks. Researchers saw evidence corroborating several of these incidents including damaged buildings and infrastructure.

For example, researchers visited the Tongoli health center, in Delami county, which was damaged in a bombing and closed in 2013. Researchers also saw damage to Heiban Royal Hospital, in Heiban county, which witnesses said was hit by a bomb delivered by an Antonov aircraft in February 2015.

In many examples of health, education, or other facilities damaged from the air attacks, Human Rights Watch was not able to establish if particular sites were intentionally targeted or if they were hit because bombs were dropped indiscriminately on the settlements.

However, in a series of aerial attacks in April and June 2014 on eight separate locations of health facilities and humanitarian supply storages, the circumstances suggest deliberate targeting. In three cases, drones flew over the sites in the days preceding the attacks.

On April 5, 2014, an Antonov dropped several bombs on and around a hospital in the village of Tujur, Delami county, said witnesses working in the facility at the time. One bomb landed in the compound of the clinic, damaging a store.

On May 1, 2014, government jets attacked Gidel hospital, the largest hospital in the rebel-held area, with three bombs that landed around the hospital, and one that landed inside the compound. On May 2, an Antonov aircraft dropped eight bombs around the hospital. Staff saw a drone circling the hospital about a week before the attacks.

On May 5, an aircraft bombed the compound of another hospital in Loweri village, also Heiban county, in a similar attack that injured one person and damaged infrastructure. As at Gidel, hospital staff reported seeing a drone a few days before the attack. The area around the hospital was bombed again on May 29.

The Kauda Rural Hospital, Heiban county, was not functioning on May 28, 2014, when aircraft fired three rockets at its compound. One landed inside the compound and the others immediately outside it.

In Kauda, the compound of the largest local humanitarian organization operating in the Nuba Mountains was also bombed in a May 2014 attack by an Anontov aircraft, but it is unclear whether it was a targeted attack or part of a number of air attacks taking place in the town at the time.

On June 16, 2014, an Antonov aircraft bombed a hospital run by the medical humanitarian agency Medicins sans Frontières (MSF, Doctors Without Borders), in Farandalla, Buram county, killing one patient and a newborn baby, injuring other patients, and destroying the emergency room, pharmacy, dressing room, and hospital kitchen.

MSF had communicated the hospital’s location to authorities in Khartoum. The same facility was attacked again in January 2015. Witnesses told Human Rights Watch that two jet airplanes dropped two bombs on the compound, causing more significant damage to the hospital. A health worker there said he last saw a drone flying over the hospital in February, raising fears that the facility could be targeted again in the government’s air campaign.

In June 2014, a government jet dropped a bomb on a food storage area of a humanitarian group operating in the region, killing a laborer. A drone was seen flying over the site two days before the attack.

Also in June, government airplanes bombed another compound of a nongovernmental group in Um Sirdiba that had been used to store aid supplies. The attack killed two civilian men and injured three.

Measles Outbreak

A measles outbreak in rebel-held areas of Southern Kordofan began in April 2014, soon after an outbreak in the nearby Yida refugee camp in South Sudan. Health officials told Human Rights Watch that they had recorded almost 2,000 suspected cases. By the end of 2014, the main hospital had treated 1,300 cases, and two clinics in Um Dorein county saw almost another 500 suspected cases.

Because of the scarcity of health infrastructure and a lack of transport, health officials expect that many more cases were unreported, and that reported cases may be “the tip of the iceberg.” About 30 children died of the disease in the main hospital but the fatality rate among children who were not able to access health services is likely to be higher.

The majority of the patients were children under age 4, born after the war started in 2011 and not vaccinated. Large scale vaccination efforts by the UN and the Sudanese government, which have continued in other parts of Sudan including government areas of Southern Kordofan, were suspended in the rebel-held areas after the Sudanese government blocked aid groups from working there.

All parties to an internal armed conflict, government forces, government-backed militias, and rebel groups alike, must allow and facilitate rapid and unimpeded passage of impartial aid for civilians in need. The Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court lists the “deprivation of access to food and medicine, calculated to bring about the destruction of part of a population” as a crime against humanity when committed as part of a widespread or systematic attack against a civilian population.

Despite the restrictions, local health workers have vaccinated tens of thousands of children in the rebel-held areas since the outbreak, stemming its rapid spread, but health workers told Human Rights Watch in April that they fear many have not been reached. Difficult terrain, insecurity including the bombing, and a shortage of working refrigerators to store the vaccine hampered efforts in hard-to-reach areas. Health official said that many children were probably missed because vaccinators were concerned that aerial bombardment could hit gatherings of children – so villages were only notified a day in advance.

The UN, the African Union and the League of Arab States have pressed for access by aid groups to rebel-held Southern Kordofan. All such efforts have failed, most recently an attempt in late 2013 for a temporary ceasefire to allow for a UN mass polio vaccination. The two sides were unable to agree on how the vaccine would be transported.

Education Under Attack

International humanitarian law protects children’s right to education, even in times of conflict, and protects schools from attack unless they become a legitimate military target – for example if turned into military barracks. Sudan’s disregard for these laws has created an education crisis in Southern Kordofan.

Government bombardment of villages and small towns in the rebel-held areas since 2011 has damaged 22 schools, and has forced students and teachers to move away from permanent structures and conduct school in grass shelters next to rocky hills, or under trees, for safety. The bombing continues to terrify students and teachers in these locations. Human Rights Watch documented five cases in which schools, or areas immediately around them, had been bombed at least three times in 2014 and 2015.

Students told Human Rights Watch they struggle to concentrate, always listening for the sound of airplanes. Classes are often suspended during periods when bombing is more intense.

Sudan’s ban on aid into rebel areas has resulted in a dearth of school materials in most schools. Teachers, paid by community members and struggling to keep schools open, had copies of textbooks in the schools Human Rights Watch visited but students did not. Students whose parents could afford exercise books reported sharing pieces of paper with poorer students.

In Tongoli school, in Delami county, a total lack of school materials meant students learned and even did their exams orally, or by writing words in the sand.

Even if students manage to finish their primary education, there are few options to continue studying and only 400 students are in secondary education in the entire region, in two remaining secondary schools. Thousands of children have turned to refugee camps in South Sudan to try and get an education.

Human Rights Watch also visited schools in the refugee camps in South Sudan and found that they were overcrowded and lacked enough teachers. In both Yida and the new camp, Ajoung Thok, schools are overcrowded. Yida has over 16,000 pupils in six schools and only 73 teachers. There is only one secondary school.

The UN has not assisted schools in Yida because the camp is considered too close to the border and too militarized to become permanent. Instead, it has provided assistance to schools and other services in Ajuong Thok, a new camp, but schools there are already congested, with some 5,300 students in four primary schools.