IV. Extrajudicial Executions

Since President Arroyo came to power in 2001, extrajudicial executions have been on the rise.

A number of local and international actors have attempted to qualify the number of victims of politically motivated killings in the Philippines since the beginning of the Arroyo administration in 2001. The conclusions of these different efforts vary, as does the methodology of data collection for each effort, and the ideology of the groups doing the collecting.

In a December 2006 update, the Philippines National Police’s investigation into political killings, Task Force Usig, concluded that there were 115 cases of “slain party list /militant members” since 2001, and 26 cases of “mediamen.”42 The human rights group Karapatan, which is closely aligned with the far-left political parties and groups, asserts that 206 people were victims of extrajudicial executions just in 2006, of whom 99 were political activists, and the remainder civilians suspected of sympathizing with leftist groups.Karapatan’s list of extrajudicial executions since Arroyo came to power in 2001 tops 800 people. Other human rights groups, such as the Philippine Alliance of Human Rights Advocates (PAHRA) and Amnesty International have also come up with different statistics for different time periods. Amnesty has estimated 50 killings between January and June in its report of August 15, 2006,43 and PAHRA gave the same number for the same period.44 The Philippine Daily Inquirer reports 299 killings between October 2001 and April 2007.45

Human Rights Watch does not have the capacity to verify any one particular set of numbers or list of victims. However, our research, based on accounts from eyewitnesses and victims’ families, found that members of the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) were responsible for many of the recent unlawful killings. The motive for the killings often appears to be the political activities, or the perceived political activities, of the victim.

The unlawful killing of individuals because of their political affiliation, or the perceived political nature of their activities, is not a new phenomenon in the Philippines. However, opposition politicians claim that killings are increasingly frequent. Congressman Teodoro Casiño, a member of the leftist Bayan Muna political party, which claims to have lost more than 100 members to illegal killings since President Arroyo came to power in 2001, explained:

We’ve had them since [President Ferdinand] Marcos’ era, and it hasn’t stopped. But we’ve noticed that since 2001 the numbers have escalated at an alarming pace. Previously, a significant number of victims were with armed underground groups. But we have noticed that since 2001 nearly all of these victims are not members of armed groups, but are members of legal groups who are very critical of the Government.46

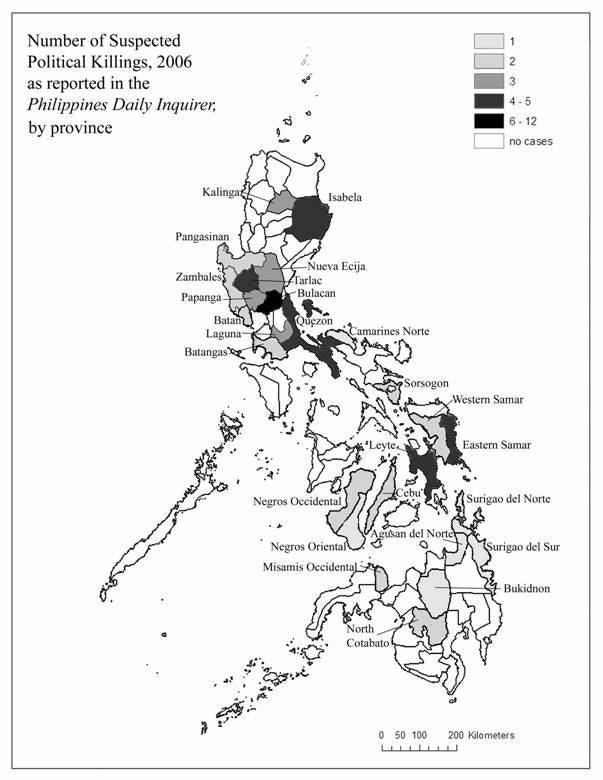

In the Philippines such killings by the security forces or by the NPA are colloquially referred to as “political killings,” and they are occurring throughout the archipelago (see Figure 1). These include instances, including “disappearances,” 47 in which individuals are abducted and never heard from again, never released, and a body is never located, leading to people being considered “disappeared.”

Figure 1: Suspected Political Killings as Reported in the Philippines Daily Inquirer during 2006, by location. © 2006 Elena Semenova

Victims of political killings or “disappearances” come from a number of professions and backgrounds, including members of the left-wing “party list” political parties Bayan Muna, Anakpawis, and Gabriela. Others includestudent activists, anti-mining activists, political journalists, clergy, and agricultural reformers.

The large number of killings does not tell the whole story. Some of the victims of this spate of extrajudicial executions had national political reputations. For example, Sotero Llamas, who was shot in his car on the morning of May 29, 2006, as he and his driver passed through his home town of Tabaco City, in Albay province, had been the former Bicol region NPA commander (see case below). The death of an individual who severed ties with the CPP-NPA many years earlier suggests that the targeted killings may not be time-bound to current activities, which can create even more fear and uncertainty in a community, particularly for those who put down their weapons years ago. The majority of victims of the political killings, however, were involved in political activism at a low-level, with at most local notoriety. The cases of two student members of the left-wing League of Filipino Students who were gunned down in the Bicol region in 2006 exemplifies this (see below).

In a few other cases involving military personnel, non-political reasons may be behind the crime. Murder has long been a common method to settle scores in the Philippines, including local political rivalries, disputes over land, corruption, and personal disputes.

Extrajudicial executions

This is how it always happens since time immemorial with these insurgency campaigns. They get out of hand.

- Governor Josie dela Cruz, Manila, September, 2006

In a number of cases of unlawful killings Human Rights Watch investigated, there was strong evidence implicating military personnel. These cases come from around the country, including five incidents in Central Luzon, two in Bicol, and two in Mindanao.

Pastor Isias de Leon Santa Rosa

The killing of Pastor Isias de Leon Santa Rosa in Bicol on August 3, 2006, provides clear physical evidence of involvement by military personnel. Just before 8 in the evening that day, there was a knock on the door. The victim’s wife Sonia Santa Rosa recounted what happened:

Immediately when I opened the door, about 10 armed men entered the house. [One of them] was shouting, commanding the others “Enter!” and to us “Lie down!” All of us lay down and they pointed guns at our heads… A short firearm. After 5 minutes they brought my husband to the room of my younger daughter… They asked him if he is Elmer. My husband did not answer. Then he answered, “I am not Elmer. You can even verify, look at my ID.” We don’t know who Elmer is. We’ve never heard the name before… All the time I was just comforting our [four] children, because the children were really crying. One of the men said “Just follow our orders and you will not be harmed.” They searched the living room and the other rooms. They took with them the laptop, the printer, and a bag of personal belongings of my husband, including some cash and cell phones, and a samurai knife that was being displayed [on the wall]… My husband was dragged out and all the men left. Knowing that the group had fled, I went outside to get the help of neighbors. I shouted “Help! Help!” Many neighbors came here, gathered here, and then we heard nine gunshots. [That was] 5 minutes after my husband was dragged out of the house… [We heard the] gunshots at about 8 p.m.48

The shots appeared to be coming from a nearby stream. Local police arriving at the ditch leading down to the stream found not one, but two, bodies. Santa Rosa’s body lay face down, and about five meters away lay another body, face up.49

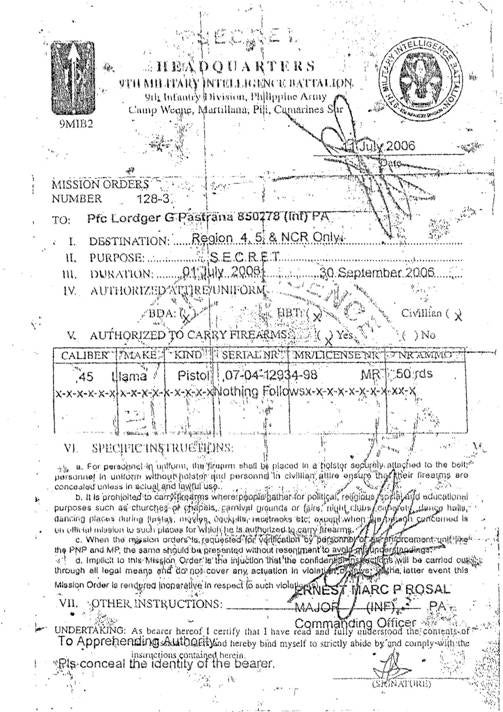

According to the police report, the second body was of a male, wearing a balaclava over his face. A .45 caliber Llama pistol and one magazine loaded with six bullets were found by the body.50 Local police also discovered a brown wallet on the body containing an AFP identification card in the name of Corporal Lordger Pastrana, serial number 850278 (see Figure 2). Also found on Pastrana’s body was a mission order marked “SECRET” from the 9th Military Intelligence Battalion for Pfc. Lordger Pastrana, serial number 850278, authorizing him to carry a .45 caliber Llama pistol from July 1, 2006, until September 30, 2006 (see

Figure 3).51 Pastor Santa Rosa’s brother confirmed to Human Rights Watch that the body belonged to one of the men who entered their house, identifying him by his clothing, and said that the dead man was the one that the rest of the men called “Sir.”52

Figure 2: A military identification card in the name of Lordger Pastrana, found on the body of one of the assailants who dragged Father Isias de Leon Santa Rosa from his home. From the police file of investigation of the killing of Isias de Leon Santa Rosa, Daraga Municipal Police. © 2006 Bede Sheppard

Figure 3: A mission order marked "SECRET" from the 9th Military Intelligence Battalion © 2006 Bede Sheppard

Forensic testing by the police of the firearm confirmed that one of the cartridge cases found at the scene of the shooting matched the pistol authorized by the AFP to Pastrana and found in his possession. However, another two slugs submitted for examination, including one found in Santa Rosa’s body, did not match the firearm.53 The official autopsy indicates that Pastrana was shot from the side, with the bullet passing from his left armpit and out through his right shoulder.54 Together, this evidence suggests—but is not conclusive—that Pastrana may have been shot by accident by another member of his team while either he or another team member attempted to execute Pastor Santa Rosa.

Sonia was uncertain why her husband was killed. According to Sonia, “My husband was a writer. He wasn’t outspoken. He wrote anti-mining brochures, against the Lafayette mining at Rapu-Rapu… [and] on [agrarian reform] issues.”55

Ricardo Ramos

Ricardo “Ric” Ramos was the president of the Central Azucarrera de Tarlac Labor Union and also a local village official. In September 2005 he received a funeral wreath that said: “RIP Ricardo Ramos.” According to Ramos’ brother, there had been a list of communist sympathizers circulated with Ramos’ name on it, along with a local village official and labor leader named Abel Ladera, who was shot and killed in March 2005.56

On the morning of October 25, 2005, the Department of Labor and Employment visited the hacienda where Ramos worked. They came to oversee the distribution of wages to the 700 or so union workers covered by an agreement that had just been struck during a strike in which Ramos had been involved. One eyewitness told us: “I noticed during the distribution of the money that the army was around. Ric [Ramos] told the soldiers to go away.”57

Two soldiers, whom the witnesses saw among these military personnel, went to see Ramos later in the afternoon. He was resting in a traditional thatch hut used as a meeting hall by the union and village leaders. Told that Ramos was sleeping, the two soldiers returned between 7 and 8 p.m. when Ramos was talking to other people, and they were again turned away and told to come back later. Around 9 o’clock that evening, a group of around 20 men were seated at a table in the hut, drinking and talking. Ramos was seated facing a wall and looking down sending a text message on his cell phone. Witnesses told Human Rights Watch that they heard two shots and saw Ramos shot in the head: “His brains splattered against the roof… with a wet sound.”58

Two eyewitnesses took Human Rights Watch to the site of the killing, then walked us away from the hut to a spot just inside a small fence by a neighboring house, from where there is a clear line of fire about 10 meters to where Ramos had been sitting. It is possible to see through the slats of the hut to the inside. The victim’s brother told us that it was here that police found two shells from an M14 rifle. The M14 is a Philippine army issued weapon, often used as a sniper rifle.

At the time of the killing, the army had a small detachment about 50 meters from where the shooting occurred. Yet it was security guards from the hacienda who were the first to respond. According to witnesses, the detachment was then removed: “That night after the killing, an [armored personnel carrier] arrived, with a large truck and a helicopter to take the soldiers away.”59

The eyewitnesses told Human Rights Watch that an arrest order had apparently been issued for the two soldiers accused of killing Ramos. However, charges against one of the accused, a private, were later dropped, and according to the victim’s brother, the remaining suspect, a sergeant with the 7th Infantry Battalion, remains free and apparently still on active service.60 “I appeal to General Esperon to execute the warrant of arrest,” Ricardo Ramos’ brother told us.61

Attempted Killing of “Nestor Gonzalez”

When Human Rights Watch met “Nestor Gonzalez,”he had been hiding in a church sanctuary with members of his family since being released from the hospital having survived being shot four times. He took one bullet to his neck, damaging the bundle of nerves running from his neck to his right arm, leaving his arm in constant pain. Nestor Gonzalez’sfamily was reliant on charity from prominent individuals in town to cover the cost of necessary painkillers and medication, and to fund an upcoming operation to improve the condition of his arm. Fighting the pain in his body, Nestor Gonzalezrecounted what he remembers of the evening in late 2006 he was shot:

That night, I was in my house taking care of my wife who just gave birth to my youngest son. Then suddenly I hear someone calling me from outside: “Big Brother! Big Brother!” When I tried to see [through the window] who was calling for me I saw a gun pointed at me, so I tried to duck, and I was shot in the neck. The police told me that the shells are from a .45 caliber pistol. I saw a small gun. I only saw one man. That was the one who shot me. He was wearing a uniform. Because it was dark, I could not know what kind of uniform, but I saw a jacket, pants, hat. Also I was not able to see his face because when I was shot the blood ran into my eyes. He said nothing… My house is made of bamboo, so I was shot at the window. It was dark outside and we had lights inside so the men could see me. This was between 7 and 8 p.m. I was shot first in the neck. After I was hit in the neck I tried to roll away to avoid the three following shots.62

Gonzalez suspected that he was shot as a result of his unwillingness to publicly support local military efforts to stamp out the NPA:

I do not know who would have wanted to kill me, because I have no enemies around the village. I have no idea. There’s no reason for me to be targeted by the military. No reason for me to be targeted by the NPA… The military conducted a village meeting, and presented a paper saying that anyone who wants to kill an NPA should sign up the paper. When it was my time to sign, I told them “I will not accept the offer because I want a peaceful life for my two children.”63

Although Nestor Gonzalezclaims that he never had any political affiliations with the left, his brother was a former member of the NPA, who had given up his arms in 1992, and local soldiers had been accusing the family of being NPA sympathizers.

Gonzalez’s brother explained that Nestor and his family had been harassed by members of the military prior to the shooting. The brother explained:

Since May, when the military came to our village, the military were inviting and interrogating [members of the community]. Some of them were beaten by the military. These people invited for interrogation and beaten by the military, they reported to our family that we should take care because we were one of the targets of the military as suspected NPA. When I learned about this from my neighbors I fled from my [home] for Manila… According to the neighbor interrogated by the military, [the military say that] our family are members of the NPA and that they would kill all of us. During the 1980s, I was a member of the NPA and I surrendered in 1992. The military knows that I was a “returnee”. [But my brother] was never in the NPA, because he is a church person, involved in church work.64

Gonzalez’shome was about 100 meters from the nearest AFP outpost. It therefore seems unlikely that any other armed, uniformed individuals would have been able to be present in the area, discharge their weapon four times, and escape without being apprehended.

According to Gonzalez’s brother, the local police unofficially conceded that the involvement of the military in the attempted murder was likely: “Based on police investigation, the suspects are the military based near [town names omitted]. Yes, the police told [our family] this based on their investigation. So the police advised us to file complaints against the military.”65

Pastor Jemias Tinambacan

Pastor Malou Tinambacan described the attack that left her husband, Pastor Jemias Tinambacan, dead. Both were members of the United Church of Christ in the Philippines (UCCP), a church involved in human rights and social justice projects that has led critics to charge that it is associated with left-wing causes and the NPA. Just past 5 o’clock on the afternoon of May 9, 2006, Malou and Jemias were driving out of the town of Lopez Jaena, Misamis Occidental, in Mindanao in a van, en route to Oroquieta to buy some printer ink. They were driving along an uphill road near the village of Mobod when they heard a bang. Jemias asked Malou: “Is that a blown tire?”66

As Malou was trying to look out a window to see what happened, two motorcycles approached the car. Two men were riding a red motorcycle, one man rode a blue motorcycle. At that moment, the van started weaving, went off the road, and struck a tree. She heard a series of shots and saw that Jemias was hit. Malou tried to duck from other shots and Jemias was leaning against her, wounded. As she lay in the well of the passenger side she heard one of the men say, “The woman is still alive.”

“It all happened very fast. I touched my hair and found an empty shell there,” Malou told Human Rights Watch.67 Her scalp was lacerated by the shell and bleeding. Terrified, she tried to lay still. “I played as if I was dead. I laid down close to the door.” She heard more shooting but then heard the sound of a bus approaching, slowing, and then the men speeding away on their motorcycles. People from the bus tried to help but, “I could see that Jemias was already dead.” He died from four .45 caliber bullet wounds.

Malou recognized the three assailants. Two are brothers who lived on land owned and rented out by Jemias’s family. One is a corporal in the Philippines army, according to Malou. She identified the third assailant as a former NPA rebel who now is known as a “military asset” – a government informant.68 She told Human Rights Watch she recognized him from “his voice.”69 Malou says that this man always called her “woman” at the church and called Jemias “man” as it was his way of telling the two apart instead of calling them each pastor.70

Malou believes the attack was motivated at least in part for political reasons. Reverend Jemias was active in local leftist politics as the provincial chairman of Bayan Muna and the executive director of an NGO called the Mission for Indigenous and Self Reliance People’s Assistance (MIPSA), which organizes local people and conducts livelihood programs.71 Several MIPSA members previously had been threatened by the military. In December 2005 a former MIPSA employee, a driver named Junico Halem, who also worked as a coordinator for Bayan Muna, was killed by two men riding on a motorcycle. That case has gone nowhere and his wife and daughters fled into hiding. The Tinambacan case is complicated by the couple’s relationship to the suspects. According to Malou, one of the brothers had come recently to Jemias and asked for 30 thousand pesos (US$620) to pay debts related to the land. Jemias refused. One possible scenario is that given the ties of the assailants to the military, they perhaps were paid to do the killing.72

Pastor Andy Pawikan

Three eyewitnesses currently in hiding told Human Rights Watch of the involvement of soldiers in the death of Pastor Andy Pawikan, a member of the UCCP. After Pastor Pawikan led church services in Pantabangan, Nueva Ecija, on May 21, 2006, at about noon, Pawikan, his wife and 7-month-old daughter, along with three women from the church headed to the Pawikan home. They were stopped by a group of about 20 soldiers. The women, including Pawikan’s wife, were allowed to proceed but the soldiers detained Pawikan, who was carrying the baby.73

After about 30 minutes, those who had just been with Pawikan heard “many” shots. They were too afraid to investigate. After some time a group of soldiers came and returned the child to Pawikan’s mother-in-law. The baby was covered in blood but otherwise uninjured.

The next day people from the village went to the area where Pawikan had been detained and found his body. They had been afraid to go there earlier because of the military presence. When they arrived there were about 10 soldiers still in the area. These soldiers, who were from the locally based 48th Infantry Battalion, told the villagers Pawikan had fought the soldiers and they had no choice but to shoot him. The soldiers insisted they had no choice. Even if one accepts that the pastor could have posed any risk to the soldiers, the villagers question how the pastor could have fought the soldiers while holding his baby daughter.74

“Gloria Fabicon”

In 2006 “Gloria Fabicon” was found dead with multiple bullet wounds. Her sister said she had been under surveillance from the AFP at least three months prior to her killing:

Before the incident, my sister… told me there was an invitation coming from the military men, and that she’s included in a list of seven names written on a piece of white paper that these soldiers told the village captain that they are looking for… They called a special meeting to confront the seven people on the [list]. My sister… was number six… Soldiers conducted a personal interview with each of them, in a home located in our town… Allegedly [according to the military], the seven persons gave support to the NPA or are a member of the NPA. My sister denied this. [The military] were from outside. Outside combat control… My sister asked my advice, and I advised my sister to consult the village captain in order to clear her name. But the village captain gave no response until now… My sister was nervous when investigated by the military men.75

A local police officer working on this case confirmed that the victim’s name had appeared on some sort of list by the military. According to this police officer, the police asked the local military to confirm whether the victim’s name appeared on any list, and the military confirmed that it had, but claimed opaquely that it was a list used “only to verify her identity.”76 However, the victim had worked for a local rights organization that critics viewed as being affiliated with the insurgency, and her family and the organization were confident that her death was a result of the victim’s work.

“Disappearance” of two women

Human Rights Watch met with a teenage boy in Central Luzon who witnessed the abduction of two women, Karen Empeno and Sherlyn Cadapan, who were conducting research sympathetic to farmers, and who are now considered to be victims of a forced disappearance. The boy described their abductors as “military men” because they were wearing camouflage fatigues, and because “They called each other ‘Sir!’ [and] it is only the military that have guns.” 77 He told us:

Around 2 a.m… I was asleep and I was awakened with [one of the women] screaming “Mother help me!” The military told us to go outside and I was tied up… Six of the military men were wearing camouflage [fatigues], the rest [of the 15 men were wearing] civilian clothes, just like anyone else. T-shirts, shorts… All of them had guns. The guns were carried in front, holding them. They were long guns. Black… Everyone was quiet. Someone said “Sir, we already have the two [women].” The military tied me up like this [with hands behind my back], and picked me up by my collar [and carried me] outside of the house. The military carried me by the back of the neck. They used plastic straw to tie my hands… They pushed me to lie down… Outside were [the two women], carried outside of the house. The six men who were wearing uniforms came out. My father was also outside. My father was also tied up… The military men asked us about our names. They asked [one of the women] and then [the other]. [The first woman] gave her name, and then [the second woman] gave her name… After that they boarded the jeep. It was a stainless [steel colored] jeep. The jeep is very long… no paint… The jeep looks like a passenger jeepney… A guy in civilian clothes was driving.78

Members of the women’s families succeeded in getting the courts to issue a writ of habeas corpus against the military for the pair, but the military has denied having them in custody.

“Manuel Balani”

Military personnel may have been involved in the killing of “Manuel Balani,” a local agrarian and anti-mining activist in late 2006. Remembering the morning before her husband was killed, Balani’s widow told us:

Before [Manuel] went to his work, at 5 or 5:30 a.m., he received a text message [on his cell phone] that he has to watch out because there is a roaming military foot patrol [nearby]—armed people in uniforms… I don’t know who sent [the text], a friend of [Manuel’s]. So I tried to convince [Manuel] not to report to work, but he received another text that the foot patrol was in an area higher up, further away from here, two kilometers from here. So [my husband] decided to report to work.79

The wife said that witnesses told her that her husband was stopped later that morning on his way to work by seven armed men in fatigues. They reportedly told her husband “You are the one who doesn’t want the [mine] to open” and then shot him dead.80 Human Rights Watch visited the location of the execution where an impromptu shrine for the victim had been built on the side of the road. Meters away, we found a tree containing a hole consistent with having been shot.

Danilo Hagosojos

Sixty-one-year old Danilo Hagosojos was riding home on his motorbike with his 7-year-old daughter who he had just picked up from school, when he was shot multiple times in the chest and head by two unidentified assailants, on July 19, 2006, in Sorsogon, in the Bicol region. Hagosojos had been a leftist activist during the rule of President Marcos and was a retired public school teacher who worked principally as a farmer during his retirement, but had also recently worked as a coordinator for a small NGO teaching literacy to rural adults.81 Hagosojos was also an uncle to then-House Minority leader Francis Escudero and a cousin of then-Vice Governor Kruni Escudero, vocal critics of the Arroyo administration.82

According to the son of Danilo Hagosojos, the local police told him that they suspected the involvement of the military in the shooting of his father: “The police told me that the suspects are military, but that it is hard for them to go there because it is dangerous to investigate about the case.”83 Although Human Rights Watch was unable to get a comment from the local police on this case, the police investigation report notes that the shooting was perpetrated “by two men of skilled, clever, disciplined, patient and determined person and very careful in exposing their identity [sic]…The commission of the crime shows that it is a well planned operation and the suspects are well versed in the [use] of firearms and very careful in exposing their identity [sic].”84 The report also recommends that the case be “temporarily closed and be reopened upon the acquisition of material evidence.”85 As described in detail in the next chapter, police appear highly reluctant to follow leads that require investigation of the military.

Armando Javier

Armando Javier was a peasant rights activist and local coordinator for the party list group Anakpawis in near Cuyapo, Nueva Ecija, Central Luzon. On the evening of October 2, 2005, Armando and his wife Jocelyn were at home watching television. They lived in a simple home with a thatch roof and split bamboo walls. Around 8:45 p.m. a hail of bullets filled the room. The police report says the assailant used an M16 assault rifle. Nine bullets hit Armando, and one grazed Jocelyn’s shoulder.86 When Human Rights Watch visited the Javier home a year after the shooting, the bullet holes were still visible in the wall.

Armando was a “rebel returnee”—having left the NPA in 1994 in order to marry Jocelyn. His name was on a list of supposed NPA sympathizers that was read off by soldiers who called villagers to meetings to inform them that their area was to be cleansed of communist influence. According to Armando’s family, a detachment of soldiers camped nearby frequently called Armando for questioning, asking him to identify members of the NPA. Because of this attention, the family is certain that the military are responsible. Javier’s mother told us: “He had no information and so he was killed.”87

Attempted Killing of Roderick Abalde

Roderick Abalde, a coordinator for the Anakpawis political party in Kidapawan City, Mindanao, survived an apparently politically motivated murder attempt on May 7, 2006. He told Human Rights Watch:

I was inside the [Anakpawis] office with the Secretary General of Bayan… We finished our talks around 9 p.m., and we were about to go to the office of Bayan to drop-off the Secretary-General of Bayan… We were still in the compound of the Anakpawis office on our motorbikes, ready to start the engines, when we discovered that there was a white DT motorcycle going from the highway… to the school, 100 to 200 meters from the office. Just a few meters in front of the school, they U-turned very quickly. We were about to start the engines and suddenly in front of my motorcycle, the persons on the white DT threw a grenade at us as he was going back to the highway… Two people were on the motorbike. There was a driver wearing a helmet, but the rider behind had no helmet… The motorcycle was about seven to 10 meters away, so I could not clearly see the [rider on the back of the bike’s] face because he was moving very fast. The back rider threw the grenade. Both men wore a white shirt and jeans. The back driver wore a sleeveless shirt. The grenade landed behind my motorcycle. Three meters behind. I never saw the grenade when it was thrown. I only found out when it exploded. I thought it was just a stone. At first I didn’t feel I was wounded. I tried to help my companion because I saw he had blood on his body. My companion was wounded in his stomach and his thigh. I didn’t discover that I was wounded until I lost my energy when I saw someone coming to try and help me… Shrapnel had entered my back and gone into my lungs. Our neighbor helped take us to the hospital… I was awake, but had blurry sight. I was in a critical condition because of the shrapnel that penetrated my lung. The shrapnel had exactly struck [my right] lung, and the lung was starting to collapse… Very painful. I was in the hospital for two weeks.88

Sotero Llamas

Three motorcycle-riding gunmen shot and killed Sotero Llamas, the former Bicol region commander of the NPA, while he was was riding in his car on the morning of May 29, 2006, through his home town of Tabaco City, in Albay province. His bodyguard was wounded in the attack.

As detailed later in this report, responsibility for the killing is unclear, but Llamas’ history raises concerns of political motivations. Llamas joined the NPA in 1971, briefly surfaced from his underground life during the ceasefire of the Aquino administration, and then was captured and imprisoned in 1995 by government forces in Sorsogon province. Released in 1996 as part of resumed peace talks, Llamas spent six months as a political consultant for the peace process, before becoming a founding member and the director of internal affairs for the political party Bayan Muna.

In 2003 Llamas left Bayan Muna for health reasons and to spend more time with his family. Llamas made a run for governor in 2004 without the backing of the leftist parties. After the election in 2004, he was in the scrap metal business. His widow says that he was completely out of the NPA and retained no more connections with the underground movement, and had not since 2003. Even the local governor, who had run against Llamas in 2004, confirmed that Llamas was no longer associated with the underground movement.89 In February 2006 Llamas was one of the 51 people whom the police accused of rebellion and insurrection and being involved in the conspiracy to overthrow the Arroyo administration.90 A judge dismissed the charges, but state prosecutors subsequently re-filed the case, which was still pending at the time of his death.

League of Filipino Students (LFS) in Bicol

Two members of the left-wing League of Filipino Students (LFS) were gunned down in Bicol in March and July 2006 respectively, and a third was shot in February 2007. The LFS is a national student organization with international affiliated chapters. Although the motives behind the killings are uncertain, LFS members have long been targeted by the security forces for alleged links to the NPA.91

Cris Hugo, the regional coordinator for LFS and a fourth-year journalism student at Bicol University, was shot and killed by an unidentified gunman on the evening of March 19, 2006, while walking along the streets of Legazpi City with one of his professors. Hugo’s professor told police he could not identify the perpetrator, and the police say that they cannot solve the crime. Provincial Governor Fernando Gonzalez questioned: “The problem here is the motives are obscure. It’s intimated that this is related to his position with the student council, and that it’s said to be a militant group—they fight for causes. But there was no indication that he was a very influential person. There was no reason [for this killing] based on his activities.”92

A friend of Hugo’s told Human Rights Watch that, prior to being gunned down, Cris had received death threats. This led Cris to attempt to change his behavior and appearance, perhaps either trying not to be identified, or because he was trying to look less radical. The friend said: “He changed his image because of these threats on his life. He got his hair cut, changed how he dressed. Before, he was not fond of wearing polo [shirts], but after the threats he looked like a seminarian. Also, he started wearing eyeglasses. From an activist to a seminarian!”93

Rei Mon “Ambo” Guran, was the LFS provincial spokesperson and a student at Aquinas University in Legazpi City in the Bicol region. Guran was shot and killed on July 31, around 6 a.m. on a crowded bus in his hometown of Bulan, in Sorsogon province. His father described him as a “jolly person [who] wanted to make people laugh in their saddest of moments. He committed no crime in his entire life… That’s why I feel so sad that my son was so brutally killed the day after his 21st birthday.”94

A third killing in the Bicol region possibly linked to membership in LFS is that of Farly Alcantara II, a 22-year-old graduating business administration student at Camarines Norte State College in the town of Daet, Camarines Norte. While riding home on a motorcycle with one of his professors in the late evening of February 16, 2007, Alcantara, a former spokesperson for LFS in the province, was shot five times in the head by unidentified men. The police found four empty shells and two slugs at the scene, and identified that Alcantara had been shot. Colonel Henry Ranola, police director of Camarines Norte, identified the weapon as a .45 caliber pistol. The professor was unhurt. 95 The gunman remains unidentified.

Ongoing impunity for military personnel

Human Rights Watch is unaware of any apparent politically motivated killing in recent years where military or police personnel were successfully prosecuted. The PNP’s Task Force Usig identified six cases implicating soldiers or militia members in political killings. However, of these six cases, four were dismissed or dropped because of a lack of evidence; in the fifth case, the soldier was discharged; and the sixth is pending before the prosecutor’s office in Naga City.96

Human Rights Watch has likewise failed to find any cases where prosecutions of commanding officers have been pursued based upon the principle of command responsibility—legal liability derived from the responsibility of commanders to control the actions of their subordinates. Instead, there is a perception that military officers who at the least condone killings of suspected NPA members, however unlawful, are rewarded. General Jovito Palparan, who was the commander of the AFP forces in Central Luzon until September 2006, told the media that the killings were “necessary incidents in a conflict. Because they [the rebels] are violent. They have killed a number of people already so we cannot just take a back seat."97 Yet General Palparan has publicly received only praise and promotion from the Arroyo administration. As Senator Biazon, the chair of the Senate’s Committee on National Defense and Security, explained to Human Rights Watch:

[There are] continuous statements, even from the President, like when she said, “I give the military two years to solve the insurgency problem in the country,”… and then she proceeds to laud the performance of General Palparan… [who], wherever he has been assigned… seems to have been a magnet to the occurrences of alleged political killings. That developed a perception that this guy is responsible for the extrajudicial killings. It may or may not be true. It may be half true. Now, when the President lauded his performance, [and made him] the poster boy of the President on counter-insurgency policies, the question of the public is, ”Is this now the policy of the Commander in Chief?” If this is not the policy, the projections to the units in the field is that it is, and that they will be protected. A perception helped along by a pronouncement to the public of an adoption of a total war against the insurgency.98

The Philippines government strenuously denies any involvement in or policy in favor of the killings. In a letter to Human Rights Watch, the Permanent Representative of the Philippine Mission to the United Nations in Geneva stated:

The administration is absolutely not involved in, nor condones, the torture and/or murder of journalists, party-list members, and military [sic] or leftist activists

The Philippine Mission also reported to Human Rights Watch that according to the Philippine National Police Chief Oscar C. Calderon, 110 members of party-list political parties have been killed during the period 2001 to October 2006, of which “military personnel are suspects in a mere 10 of the above incidents while a police member is a suspect in 1 incident.”100 Human Rights Watch notes that according to the government’s own assessment its security forces are already suspects in 10 percent of cases of killings.

42 Philippines National Police, “Update on Tasforce ‘Usig’,” December 11, 2006.

43 Amnesty International, “Philippines: Political Killings, Human Rights and the Peace Process,” August 15, 2006, section 1.

44 Human Rights Watch interview with Max De Mesa, PAHRA Chairperson, September 12, 2006.

45 See e.g. Alcuin Papa, “3 US solons to PNP: Respect human rights,” Philippine Daily Inquirer, April 18, 2007.

46 Human Rights Watch interview with Representative Teodoro A. Casiño, Party-List Representative for Bayan Muna, National House of Representatives, September 12,2006.

47 According to the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons From Enforced Disappearance, “enforced disappearance is considered to be the arrest, detention, abduction or any other form of deprivation of liberty committed by agents of the State or by persons or groups of persons acting with the authorization, support or acquiescence of the State, followed by a refusal to acknowledge the deprivation of liberty or by concealment of the fate or whereabouts of the disappeared person, which place such a person outside the protection of the law” (Article 2), E/CN.4/2005/WG.22/WP.1/REV.4, 23 September 2005, (not yet in force).

48 Human Rights Watch interview with Sonia Santa Rosa, September 20, 2006.

49 Crime Scene Sketch from Daraga Municipal Police, copy on file with Human Rights Watch; Human Rights Watch interview with Ray Sun Santa Rosa, September 20, 2006.

50 Memorandum, Daraga Municipal Police Station, August 21, 2006.

51 Photocopy of AFP ID and mission order on file with Human Rights Watch.

52 Human Rights Watch interview with Ray Sun Santa Rosa, September 20, 2006.

53 Firearms Identification Report No. FAIB-67-2006, Regional Crime Laboratory Office 5, Camp General Simeon A Ola, Legazpi City; Firearms Identification Report No. FAIB-76-2006, Regional Crime Laboratory Office 5, Camp General Simeon A Ola, Legazpi City.

54 Autopsy Result, Lordeger Pastrana, August 8, 2006. Copy on record with Human Rights Watch. The autopsy indicates gunshot point of entry at left axilla, and point of exit at right deltoid area.

55 Human Rights Watch interview with Sonia Santa Rosa, September 20, 2006.

56 Human Rights Watch interview with Romero Ramos, October 28, 2006.

57 Human Rights Watch interview with George Gans, October 28, 2006.

58 Human Rights Watch interview with George Gans, October 28, 2006.

59 Human Rights Watch interview with Romero Ramos, October 28, 2006.

60 Human Rights Watch interview with Romero Ramos, October 28, 2006.

61 Human Rights Watch interview with Romero Ramos, October 28, 2006.

62 Human Rights Watch interview with Nestor Gonzalez (not his real name), date omitted, 2006.

63 Human Rights Watch interview with Nestor Gonzalez (not his real name), date omitted, 2006.

64 Human Rights Watch interview with Joseph Gonzalez (not his real name), date omitted, 2006.

65 Human Rights Watch interview with Joseph Gonzalez (not his real name), date omitted, 2006.

66 Human Rights Watch interview with Reverend Marielou “Malou” Lumayad Tinambacan, November 2006.

67 Human Rights Watch interview with Reverend Marielou “Malou” Lumayad Tinambacan, November 2006.

68 Human Rights Watch interview with Reverend Marielou “Malou” Lumayad Tinambacan, November 2006.

69 Human Rights Watch interview with Reverend Marielou “Malou” Lumayad Tinambacan,November 2006.

70 Human Rights Watch interview with Reverend Marielou “Malou” Lumayad Tinambacan, November 2006.

71 Human Rights Watch interview with Reverend Marielou “Malou” Lumayad Tinambacan, November 2006.

72 Human Rights Watch interview with Reverend Marielou “Malou” Lumayad Tinambacan, November2006.

73 Human Rights Watch interview with Conrado Alarilla, Jose Gomez, and Joey Castillo (not their real names), October 14, 2006.

74 Human Rights Watch interview with Conrado Alarilla, Jose Gomez, and Joey Castillo (not their real names), October 14, 2006.

75 Human Rights Watch interview with Maria Fabicon (not her real name), date withheld, 2006.

76 Human Rights Watch interview with Chief of Police working on case (name and date withheld).

77 Human Rights Watch interview with Antonio Pestana, (not his real name), date withheld, 2006.

78 Human Rights Watch interview with Antonio Pestana, (not his real name), date withheld, 2006.

79 Human Rights interview with Maria Balani (not her real name), date withheld, 2006.

80 Human Rights interview with Maria Balani (not her real name), date withheld, 2006; a local human rights NGO also confirmed to Human Rights Watch that witnesses they had spoken to confirmed this series of events.

81 Human Rights Watch interview with Ian Hagosojos, September 21, 2006; Human Rights interview with Belen Santos, September 21, 2006.

82 “Rights Group Leader Shot Dead in Sorsogon,” Philippines Daily Inquirer, July 21, 2006.

83 Human Rights Watch interview with Ian Hagosojos, September 21, 2006.

84 Investigation Report, July 20, 2006, Casiguran Municipal Police Station.

85 Investigation Report, July 20, 2006, Casiguran Municipal Police Station.

86 Human Rights Watch interview with Jocelyn Javier, October 27, 2006.

87 Human Rights Watch interview, October 27, 2006.

88 Human Rights Watch interview with Roderick Abalde, September 15, 2006.

89 Human Rights Watch interview with Fernando Gonzalez, Governor of Albay, September 20, 2006.

90 “Four party-list representatives among 51 persons linked to conspiracy to oust PGMA,” Official website of the Republic of the Philippines, February 27, 2006, http://www.gov. ph/news/default.asp?i=14522.

91 See, for example, Lawyers Committee for Human Rights, Vigilantes in the Philippines, pp. 32-33.

92 Human Rights Watch interview with Fernando Gonzalez, Governor of Albay, September 20, 2006.

93 Human Rights Watch interview with Lessa Lopez, September 19, 2006.

94 Human Rights Watch interview with Arnel Guran, September 21, 2006.

95 Randy David, “Now, they’re killing students,” Philippine Daily Inquirer, February 18, 2007; Ephraim Aguilar, “Student activist slain in Camarines,” Philippine Daily Inquirer, February 17, 2007.

96 Christine Avendaño and Dona Pazzibugan, “Arroyo to seek Europe help in probing slays. Melo panel told: Why stop with Palparan?,” Philippine Daily Inquirer, January 31, 2007.

97 General Jovito Palparan, as quoted in “General Palparan: Leftist rebellion can be solved in 2 years,” Agence France Presses, February 2, 2006; and quoted in Fe B. Zamora, “In his all-out war against the reds, this General dubbed the butcher claims conscience is the least of his concerns,” Sunday Inquirer Magazine, July 2, 2006.

98 Human Rights Watch interview with Senator Rodolgo Biazon, Senate Office, September 13, 2006.

100 Letter to Human Rights Watch from Enrique A. Manalo, Permanent Representative, Philippine Mission to the United Nations and Other International Organizations, October 12, 2006.