V. Failures to Investigate and Prosecute

The killing is not just between the people, because it has an impact on the whole community, that you can just kill someone.

—Father Jovic Lobrigo, Albay, September 2006101

The Philippines government is consistently failing in its obligations under international human rights law to hold accountable perpetrators of politically motivated killings. Victims’ families are denied the justice they deserve as the killers literally get away with murder. With inconclusive investigations, implausible suspects, and no convictions, impunity prevails.

Lack of Successful Prosecutions

Although a handful of hitmen have been successfully prosecuted for murdering journalists, Human Rights Watch could not identify a single successful prosecution for any of the political killings in recent years cited by local civil society and human rights groups. Importantly, despite the evidence of the involvement of military personnel in many killings in recent years, data from the Armed Forces of the Philippines confirms that as of March 2007 no military individual has yet been convicted. The armed forces indicate that they believe that just 12 accusations have been made against specific individual officers and enlisted personnel of the AFP. Out of these 12 cases, three cases have charges pending, five have been settled, acquitted, or dismissed by the DOJ, and four cases still remain “under investigation.”102

Of the three cases filed in court:

- Corporal Alberto Rafon, went “Absent Without Leave” (AWOL) while being investigated and was thus discharged from the military. The military states he is therefore no longer under their jurisdiction.

- Corporal Estaban Vibar, is currently in custody.

- Master Sergeant Antonio Torilla, has been charged with three counts of murder, however, the military contends that the killings were the result of “legitimate encounter against DTs (dissident terrorists).”103

The United Nations Special Rapporteur on Extrajudicial Execution concluded after his investigation to the Philippines that “on paper,” accountability mechanisms in the country remain strong. However: “there is a passivity, bordering on an abdication of responsibility, which affects the way in which key institutions and actors approach their responsibilities in relation to such human rights concerns.”104 The Special Rapporteur went on to criticize prosecutors for refusing to take a role in gathering evidence, and instead being purely passive, waiting for the police to present them with a file, and if the file was insufficient, seeing their role as being simply to return it and hope that the police would do better next time. The Special Rapporteur further criticized the Ombudsman’s office for, despite the existence of a separate unit designed to investigate precisely the type of killings that have been alleged, having “done almost nothing in recent years in this regard,” failing to act in any of the 44 complaints alleging extrajudicial executions attributed to State agents submitted from 2002 to 2006.105

State responsibility and command responsibility

One apparent roadblock to prosecutions is the seeming unwillingness of senior military officials to even recognize that superior commanders may be legally responsible for acts of their subordinates as a matter of command resp0nsibility.106 AFP Chief of Staff, General Hermogenes Esperon, Jr. told the media: “Criminal acts only involve the individual.”107 In testimony before the Melo Commission—the Commission created by Arroyo in August 2006 to investigate the killings of media workers and left-wing activists—General Esperon similarly claimed that command responsibility does not include criminal liability for a superior officer when subordinates commit an illegal act that is criminal in nature.108

Philippine commanders have suggested that investigations of military personnel for alleged offenses are detrimental to the armed forces. In his same testimony to the Melo Commission, General Esperon claimed that carrying out an investigation into the actions of General Palparan while he was still an active member of the armed services and “neutralizing the NPA” would have been “unproductive.”109 He also added that investigations could “muddle, or obstruct any on-going operation.”110 This view by the head of the AFP is of serious concern, as it sends worrying signals to lower officers that they are free to act with impunity. General Esperon’s negative view of the impact of investigations is also mistaken: prosecuting soldiers for human rights violations serves to promote discipline within the forces, demonstrates respect for the rule of law, and reassures the public of the military's role in protecting the lives of civilians.

A state is responsible for violations of international human rights and humanitarian law committed by members of their armed forces or other state entities and their agents. This also includes persons empowered to exercise elements of governmental authority, such as militias. A state remains responsible for such acts even when the individuals involved exceed authority or contravene instructions.111

Under international principals of command responsibility (or superior responsibility), superior officers can be held criminally liable for the actions of their subordinates, when the superior knew or had reason to know, that their subordinate was about to commit or had committed a crime, and the superior failed to take necessary and reasonable measures to prevent the crime or to punish the perpetrator.

The duty to prevent a crime renders a military superior officer responsible for the resulting crime when the superior fails to consider elements that point to the likelihood that such crime would be committed. This would include if a commander is aware of a series of killings being committed by his or her subordinates and does nothing to prevent them. Superior officers only successfully discharge their duty to prevent crimes carried out by subordinate soldiers when they employ every means in their power to do so, including providing appropriate training and orders, and carrying out vigorous investigations and prosecutions in the case of violations. The failure of superior officers to carry out investigations or to take action against soldiers involved in the killings or “disappearance” of civilians also leads to military liability.112 Military commanders are also responsible for ensuring that their subordinates are aware of the laws of armed conflict.113

The Melo Commission’s official findings state that “there is certainly evidence pointing the finger of suspicion at some elements and personalities in the armed forces, in particular General Palparan, as responsible for an undetermined number of killings, by allowing, tolerating, and even encouraging the killings.”114 Noting that General Palparan had told the Commission that if his men kill civilians suspected of NPA connections, “it is their call [about whether to do so],” the Commission concluded that “under the doctrine of command responsibility, General Palparan admitted his guilt of the said crimes… Worse, he admittedly offers encouragement and ‘inspiration’ to those who may have been responsible for the killings.”115 Accordingly, the Commission concluded that General Palparan “may be held responsible for failing to prevent, punish, or condemn the killings under the principle of command responsibility.”116 Human Rights Watch welcomes any such investigation by prosecutorial agencies into whether it is appropriate to hold General Palparan accountable under the doctrine of command responsibility. However, the scope and depth of the current problem of extrajudicial executions by members of the military requires that any investigation not be limited to only one individual, but should extend to all who may be responsible for serious criminal offenses, including active duty officers and civilian officials.

“Solved” cases unsolved

Police in the Philippines appear all too willing to call a case “solved,” regardless of whether a perpetrator has been arrested, or even identified.

According to the police, a case is labeled “solved” when a suspect has been identified and charges have been filed before the prosecutor or the court.117 Such a definition is deceptive, as it includes cases where the persons accused and the evidence presented are so uncertain as to raise significant doubts that a viable case could ever be presented before a court. The alleged perpetrator is very rarely in custody or is not even capable of being apprehended, since those named are frequently long-wanted members of the NPA, or the alleged assailants are referred to only by the moniker “John Doe” –to indicate that the perpetrator’s identity is actually unknown.

For example, the case of George and Maricel Vigo has been deemed “solved” since June 23, 2006—a week after they were killed—when a criminal complaint was filed before the city prosecutor’s office against an alleged former member of the NPA and three “John Doe’s.” The Vigo couple worked in Kidapawan, North Cotabato, on Mindanao for a small NGO called the People’s Kauyahan Foundation, and George Vigo had a local radio show which dealt with agrarian reform issues. The Vigos were also political supporters of a local congresswoman and another woman who was running for mayor against an entrenched local politician. The pair were gunned down by four assailants on motorcycles while they rode together on a motorcycle on June 19, 2006.

The police considered the case solved despite failing to identify three of the suspects, or locate the fourth. The investigators apparently gave up their efforts to identify the perpetrators after just three days. As a relative of the Vigos explained:

During the wake for Maricel and George, [then Chief of the PNP] General [Arturo] Lomibao came, and before he left he assured us that the killing of George and Maricel would be given justice. He assured us that as soon as possible George and Maricel would be given justice. The next day, the PNP made a group—”Task Force Vigo”—and then they pinpointed a man after just three days.118

However, neither of the victims’ mothers (see Figure 4) is satisfied that the case is closed.119

Figure 4: The mothers of George and Maricel Vigo hold pictures of their children-in-law. © 2006 Lin Neumann/Human Rights Watch

Poor policing

In the provinces there is a real lack of faith in the police and the justice system.

—Glenda Gloria, Managing Editor, Newsbreak magazine, Manila, September 2006120

Public distrust in the government’s investigative effort is profound. Witnesses and victims’ families interviewed by Human Rights Watch said they expect no real results from government investigations, and they predict impunity for those involved in the killings.

The brother of slain labor activist Ricardo Ramos told Human Rights Watch that an arrest order had been issued on June 6, 2006, for the accused killer, Sergeant Roderick de la Cruz, a soldier with the 7th Infantry Battalion stationed at Fort Magsaysay in Central Luzon. Yet the police appear to have failed to execute the arrest order. According to the brother, he and others have seen the accused soldier wandering around the local hacienda and in Tarlac City: “He appears to be on active service. The government is just fooling

Families consistently told us that they received little or no information from the police about the state of the investigation, and that the police show almost no concern as to whether the victim’s family still has unanswered questions or concerns. One widow explained: “We’ve had no contact [with the police] since the killing until this letter [we just received]. That’s why we don’t trust them. Because it’s been almost two months, and the investigation doesn’t seem resolved.”123

Some of the poor policing practices indicate a lack of police interest in conducting a credible investigation. The sister of one victim shared this concern: “After the internment of my sister, the police investigators invited me to come talk to them… Okay, I went. They asked me for my statement, so I gave them the same statement I’m giving you now. But I noticed that the investigator did not write down my statement… They did nothing.”124

A similar lack of commitment to carry out serious investigations is evident in the case of the killing of Danilo Hagosojos. The police investigation report relates eyewitness testimony regarding the shooting, including the fact that the perpetrators stole the motorcycle of the victim, and the directions used by the perpetrators to escape. The report also notes that ballistic evidence was collected at the scene of the shooting. Despite all this preliminary evidence, and the fact that the investigation report was written just one day following the shooting, the report nonetheless goes on to say that it is, “Highly recommended that this case be temporarily closed and be reopened upon the acquisition of material evidence, either physical or testimonial.”125 Hagosojos’ son told Human Rights Watch: “When I got the police report saying that because of the sensitivity of the case [they were going] to close it temporarily until strong evidence will come out, my suggestion to them was ‘You should not wait for strong evidence to just come up. As police, you have to investigate.’”126 Hagosojos’ son was led to believe by the local police that the “sensitivity” involved in the case was the possible involvement of the military stationed nearby in the killing.127

One father expressed similar exasperation with the unwillingness of the police to actually investigate. He told us that the investigation into his son’s shooting was “still ongoing, but these agencies are very much dependent on us in soliciting witnesses and some news.”128

On July 6 the police filed murder charges against alleged NPA members Edgardo Sevilla, Edgar Calag, ex-military corporal Totoy Calag, and a “John Doe” for the killing of Sotero Llamas.129 Although the police did name suspects as current members of the NPA (a finding that the family disputes), records from the local city prosecutor’s office regarding the initial hearing against the accused, indicate that the police made little or no effort to locate, let alone arrest, the individuals. First, the police had not provided either accurate or complete addresses for the accused individuals, which is a procedural necessity in the eyes of the prosecutor in order to subpoena the individuals to appear at their hearing. However, it emerges from the prosecutor’s notes that the effort required to obtain the necessary information was minimal, but the police had simply failed to make the necessary effort prior to the scheduled hearing: “When queried further as the correct and complete family residences of the [the accused], [the] police officers [had] difficulty giving them for several minutes; but at last they were able to do so after conferring with each other and by supposedly contacting through cellular phone their colleagues while the hearing was going on.”130 Thus, the date set aside for consideration of the evidence and merits of the case was lost due to procedural deficiencies caused by a failure of the police to collect even the most basic information on the individuals that they accused of being involved in a murder.

The manner in which a suspect in the case of the killings of George and Maricel Vigo was identified contains worrying inconsistencies. In the June 9, 2006, police report on the killings the police note that:

Based on the account of the witnesses, the driver of Honda XL motorcycle [ridden by the perpetrators] was wearing a safety helmet and black jacket while his back rider who shot to death the couple was wearing white t-shirt with face towel covered on his head and face, wherein the witnesses could not identify them.131

Sworn statements collected by the police from two witnesses who saw the shooting and helped take the bodies to hospital, also confirm that one of the riders was wearing a helmet, while the other wore a handkerchief or a towel over the lower half of his face. However, by the time of the complaint filed by “Task force Vigo,” the police allege there were four perpetrators, and the complaint contained cartographic sketches showing the full faces of three of the suspects, and one with his face covered with a towel.

The basis by which the suspects in the case were identified is also of concern. The one named accused in the case was identified from a cartographic sketch produced by one individual who did not actually see the shooting take place, but who saw a “suspicious looking person” among the crowd of policemen and onlookers following the shooting. According to this witness: “this man who wore a dark jacket, had a helmet in his left arm, busy texting, more or less five feet tall, medium built… When I looked into his eyes, he also looked at me sharply and his eyes were seemingly at the state of anger.”132 The police suspect was also apparently identified by a man who claims to have seen the suspect in his billiards hall two days prior to the shooting with a gun tucked in the back waistband of his pants.133

Another composite sketch was taken from a shopkeeper who was inside his shop at the time of the shooting, but who later that day saw one man on a red Kawasaki motorcycle who stopped and asked about the route to a nearby place, but who was driving in the wrong direction. This store owner told the police “I suspected him to be involved in the shooting to death because of his actuation [sic] and he is very much uneasy when he asked me and then he immediately left the place.”134

The mother of Maricel Vigo, who does not speak English, told us how local police tricked her into filing a complaint against the suspect pinpointed by the police:

Two policemen came here and told me to go to the police station and asked me to sign an affidavit that allegedly said that Maricel and George were my children. It was in English. The police did not explain what the context was except that. I did not know that it said in the last paragraph that I was signing a complaint saying [this man] is the killer…. When I realized from my daughter what I had been made sign, I got so mad and angry, and I was crying.135

The suspects in the Vigos case remain at large.

The high level of suspicion about the police meant that Roderick Abalde, who survived a grenade attack on a local Bayan Muna party office, did not even report the attack to the local police. He told us:

I did not complain to the police because it was not clearly identified who did the throwing of the grenade. For me, it would be useless, because it already [appeared] that it was part of the plan of the regime to repress those who are critical and progressive. We have already had this scenario that if you complain to the police nothing will happen. Like in General Santos [City], where a grenade was thrown and nothing came from the investigations. So we felt that it would be useless. Even the past bombing in Kidapawan City had no report.136

In only one of the incidents investigated by Human Rights Watch had a suspect even been arrested by the police.

Harassment of families and acquaintances following killings

Following a killing, surviving family members or close acquaintances of victims reported to Human Rights Watch of harassment or intimidation from anonymous sources, some of which they perceived as death threats.

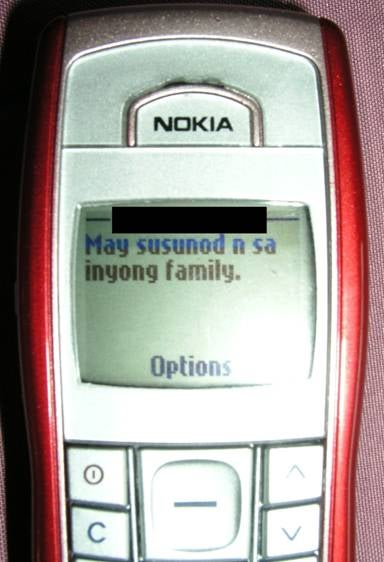

The oldest daughter of Sotero Llamas showed Human Rights Watch a text message received on her mobile phone reading “Another person in your family will be next” (see Figure 5). She explained:

At the moment I’m receiving texts saying someone will follow members of the family. I don’t know if it’s a threat or a warning. He says in some of the texts that he knows who killed my father and that I should go talk to him. I don’t know who he is. I just have his number… [I’ve received around] twenty. Saying things like “Don’t investigate or we’ll get your family.”137

The daughter has kept a log of the messages she has received, which she shared. Previous messages included “If I tell you who shot your Father will you meet me?,” “If you won’t, I will meet you anywhere, your husband and I are always in the same bus,” and “I will wait for you at the corner.”138

Figure 5: A threatening text message to Sotero Llamas' daughter warns "Another person in your family will be next." © 2006 Bede Sheppard

Malou Tinambacan, an ordained pastor of the United Church of Christ, has also received text messages that have frightened her since the death of her husband. One read “Be Careful.”139 After the shooting of her husband Malou is still afraid because she saw unfamiliar men hanging around the office of her husband’s organization, and she worried that she too might be killed. Malou left Mindanao out of such safety concerns.

The mother of Maricel Vigo told Human Rights Watch: “After the killings there were warnings. Information was being passed around that we would be next.”140 Her son also believes he is being watched and followed by men on motorcycles: “They haven’t talked to me, but I know that they are doing surveillance on me.”141

The younger brother of Pastor Santa Rosa shared similar concerns:

We want to go to the city because we fear for our safety, because I noticed that when I am out there are unidentified people following me, riding on a motorcycle. It’s already been three times. One time I saw they were carrying a gun. [This was] recently, [each incident] about three days apart. From here [at home] they followed me to outside the city. They were looking suspicious. They looked like a military person [in their physique and posture]. They were wearing a cap almost covering their face. And when I stopped, they looked at me.142

Villagers from the hometown of Pastor Andy Pawikan, who was believed killed on May 21, 2006, told Human Rights Watch that a week after Pawikan’s body was found a squad of seven soldiers came to the village and fired their guns in the air.143

Two families told Human Rights Watch that government security forces monitored the funerals held following killings in a manner that the families found harassing.144 On the day of the funeral for Danilo Hagosojos, family members reported that:

At 6 a.m. on the day of the funeral, three helicopters were hovering around town… While the priest was celebrating mass, [a] helicopter was going around the church. [It was flying] very low. The soldiers could have almost easily jumped [out to the ground. It was probably] because there were some human rights activists who had joined us during the funeral.145

Witnesses and victims’ families’ fears of retribution

Up until now there is no progress in the investigation, because, according to the investigators, no one wants to be a witness… There is no cooperation… They cannot convince the witnesses to tell the truth.

—Mother of victim, September 2006

As long as the military stays in our [village], the threat is still there and we won’t go back.

—A man attacked allegedly by military personnel who is currently living in hiding, September 2006

Witnesses and victims’ families are being scared silent. Numerous families told Human Rights Watch that they are afraid to cooperate with police because of a deep fear of becoming a target for reprisal by the perpetrators. After all, these families note, the perpetrators are armed and have so far proven their ability to act with impunity. A number of family members and witnesses have taken their protection into their own hands, and have fled their homes to live in hiding either in bigger cities or in the sanctuary of churches. Many witnesses were unwilling to be interviewed by Human Rights Watch, despite assurances we made about protecting their anonymity and offers to interview them outside of their home villages to avoid surveillance by local security forces.

At a hearing before the US Senate in March 2007, Bishop Eliezer Pascua, the General Secretary to the UCCP, which reports 15 members killed since 2001, said:

With such an appalling death toll of extrajudicial killings in our country at this time of the Arroyo administration, nobody could ever claim that she/he is not afraid… I admit that I have that fear… much more with those who have always been there who were close or in proximity with the victims within their household or even in their community when they were assassinated. You can all imagine the chilling effect among the people that these extralegal killings have been causing.146

A witness protection program is provided for under Philippine law, but it provides little real protection in practice. Under the Witness Protection Security and Benefit Act,147 the Department of Justice is tasked with providing secure housing and a means of livelihood to “any person who has witnessed or has knowledge or information on the commission of a crime and has testified or is testifying or about to testify before any judicial or quasi-judicial body, or before any investigating authority.”148 Yet police consistently fail to offer or arrange protection, and victims and witnesses are wary of having to rely on the government for protection while they are accusing government officials of serious abuses, including murder.

According to human rights lawyer Romy Capulong: “We have a very weak witness protection program… We have experienced instances of building cases and filing cases only to have them fall apart in court because witnesses refused to testify for some reason.”149

There are also serious structural concerns involved with a witness protection program run by the police, given that many witnesses and family members may perceive the police as being closely aligned with the military—the very group from whom they fear they need protection.

The ineffectiveness of current witness protection is illustrated in the case of the Santa Rosa family. The local Chief of Police investigating the killing of Pastor Santa Rosa told Human Rights Watch “I have asked my higher-ups to provide me money to provide security to the family,”150 but as of more than seven weeks after the shooting, the police had not provided any protection to the family, except for asking local officials to patrol the area more.

The only individual that Human Rights Watch has found to have received witness protection in a murder case actually was a soldier, Sergeant Rowie Barua, a member of a military intelligence company stationed in Cotabato City.151 Barua was originally arrested along with three accomplices in connection with the murder of Marlene Esperat, a journalist and whistleblower shot in the face in front of her children on March 24, 2005, in Tacurong City, Sultan Kudarat. As a former employee in the Department of Agriculture, Esperat had uncovered various cases of graft and corrupt practices by public officials. Following his arrest Sgt. Barua opted to become a prosecution witness, testifying that on the order of two officials in the Department of Agriculture—Osmeña Montañer and Estrella Sabay—he had arranged the hitmen who carried out the killing. A court in Cebu City convicted Barua’s three accomplices—former Sergeant Estanislao Bismanos, Gerry Cabayag, and Randy Grecia—while Barua himself was acquitted for insufficiency of evidence.152 The criminal case against the two alleged masterminds is still pending.

Government officials frequently cite the lack of willing witnesses as an excuse for failed investigations or even to impugn the credibility of the cases. But this misplaces the blame, as it is the government’s failure to provide credible assurances of protection and a poor track record of successful prosecutions.

The sister of Danilo Hagosogos explained to us why witnesses to the shooting of her brother are reluctant to testify to the police: “It’s life preservation. They are concerned for their lives, for themselves and their family. Because they know that [the perpetrators] were military, and they are always there. They don’t want to testify in court or sign any statement. Their lips are sealed.”153

A lawyer working on one case for a victim’s family told us: “The witnesses that I have talked to seem reluctant to testify because of fear for their lives if the [local political family] are still there.”154 The daughter of another victim explained: “There were witnesses, but they’re afraid. And they remain silent until this time. They’re afraid to also get killed. They are [scared of] the killers of my father.”155

When Human Rights Watch interviewed Maria Balani she was visibly nervous to be talking to us about what had happened to her husband, Manuel. She spoke in a hushed whisper, and her eyes darted constantly around, checking to see if any of her neighbors were watching or listening in, and quieting whenever a stranger approached. She informed us what has happened to the witnesses to her husband’s killing:

[One witness] has already disappeared. The other witnesses are afraid of the situation here. They are afraid that the perpetrators will begin to kill them also, because they were [warned] by the perpetrators that they will come back and kill them if they talk about the incident… I am afraid that their families will also be killed if they stand up regarding the incident…. If I push the case I’m afraid of what might happen to [me and my family]. So I’m not quite sure if I’ll pursue the case or not.156

Concerns about security also prevent victim’s families from pushing the local authorities to carry out a thorough investigation. One family member told us how she was petrified of having any contact with local security forces following the killing of her sister:

I am afraid to pursue the case. After the internment of my sister, [a representative of the] Civil Relations Service of the AFP nearby told me that he wants to talk to me. He wants me to come talk to him. But I refused. Sorry. I ignored the request… I’m also afraid when I go home at night. Please, pray for my protection. I’m in text communication [with my sister’s] children, because I’m too afraid to go to them.157

The governor of Bulacan, Josie dela Cruz, has been active and outspoken in trying to find justice for citizens in her province. Even though she is the senior political figure in her province, she shared with Human Rights Watch the difficulties even she has convincing witnesses and families of victims to provide evidence. Governor dela Cruz told us: “People are so afraid that they would rather leave Bulacan than file an affidavit of complaint.”158

According to the governor, in one “disappearance” case, “the wife appealed [to us] to be silent about it, because she was told if she keeps quiet then [her husband] will be returned. But I have to conclude that those who have not come back are probably dead.”159 In another “disappearance” case, where a man was taken from his home, she said: “The family was the most aggressive in asking me to leave the case alone.… They did not report it right away.… The mother might still be hoping. And that’s the thing, I want to get to the bottom, but in most cases the family would rather not [risk the consequences of the attention].”160

Jocelyn Javier abandoned her home and some of her most precious possessions when she fled following the killing of her husband, afraid that the soldiers she blames for her husband’s murder would return to kill her. It was not until a year later that Jocelyn returned to her home again for a visit with Human Rights Watch. Portions of the simple thatch roof have fallen in and the split bamboo walls were in disrepair. Most of the furnishings in the one-room dwelling were gone. The bullet holes are still visible in the bamboo walls. In addition to losing her husband, because of her fear of returning, Jocelyn had also lost her home. “My house is gone,” she cried.161

When the police have difficulty getting witnesses to come forward they may put pressure on the families to try and convince witnesses to testify. The cousin of Rei-Mon Guran told us:

The local police were at the home of [the victim’s parents], and asked us for help in finding witnesses because according to them they had a lot of difficulty finding witnesses because witnesses believed that the perpetrator was a member of the military, which is why they had mistrust about telling [what they saw]. This is why the agencies wanted us to get in touch with witnesses to establish trust.162

Families typically lack the necessary resources to protect witnesses. As the victim’s cousin said: “I asked [the police] what security measures can they give us, because it’s very difficult and risky for us to get witnesses. We don’t have any guns or any money to get witnesses.”163 Families in a criminal matter should not have to bear the burden of finding witnesses or protecting witnesses. Unlawful killings—especially those committed by government security forces—are a crime against the whole of society, and it is therefore the government’s duty to actively locate and prosecute those responsible.

Witnesses need protection so as to feel safe to come forward. This is particularly the case when the perpetrators are suspected of being local military forces or other strong political players. Police must earn cooperation from victims and witnesses, but bad community relations, general mistrust by victims families of the government security forces, and poor policing are impediments to building such trust.

Impediments to investigating military involvement in political killings

Philippines law provide the national police jurisdiction over all criminal offenses, including those committed by members of the armed forces. Yet intransigence by military personnel in response to investigations by civilian authorities presents a clear impediment to effective investigations and prosecutions. The Philippines military is an obstacle, rather than a facilitator of criminal investigations by the police. As a result, the police frequently and routinely fail to pursue credible leads when they indicate the involvement of military personnel in serious crimes.

For instance, in the case of Nestor Gonzalez, police were utterly unwilling to pursue investigations that may point to military involvement. According to Gonzalez’ brother:

Based on the police investigation, the suspects are the military based near [town names omitted]. Yes, the police told [our family that it was the military] based on their investigation. So the police advised us to file complaints against the military. The detachment is 100 meters from [my brother’s] home. The police told us that we should file but didn’t say that the police would file [any case] against the military.164

Gonzalez’ brother decided not to file a complaint, in part because the family was concerned that they were exposing themselves to risk with no certainty that the police would push the investigation forward.

Rather than pursuing investigations themselves against the suspected perpetrators, the police have given the Gonzalez family the invidious choice of receiving no justice or directly confronting the military themselves. It is not the victim’s burden to challenge those suspected of a criminal offense; it is the responsibility of the state.

The impotence of the police when it comes to investigating possible illegal activity by the military is illustrated by the observation of Jose Lipa Capinpin, the chief of police in Daraga, in eastern Luzon who told us: “The whole area of Daraga is supposed to be my area, but there are many parts of my area that I can’t conduct investigations because they’re [within the area of operations of] the Filipino Army.”165 But it is not the case that the police are legally unable to investigate the military; it is simply that they choose not to do so.

Chief Capinpin went on to explain the efforts that his office had undertaken in the investigation into the killing of Pastor Santa Rose, who was found dead alongside one of the suspected perpetrators, Colonel Lordger Pastrana: “I wrote a letter to the unit where Pastrana was at the time. And there’s no response yet.”166 When Human Rights Watch pressed Chief Capinpin further on how long the military had been delaying, he answered that he had only gotten around to following the lead of asking the local battalion about Pastrana “yesterday”—more than seven weeks after Pastor Santa Rosa was murdered. Instead, the police’s earlier approach was to rely on the family members to identify the suspects.

The local head of the governmental Commission for Human Rights was a little quicker to approach Colonel Pastrana’s unit to ask for an explanation. According to Director Pelagio Señar, he spoke with Pastrana’s commanding officer, as indicated on Pastrana’s mission order, who denied that Pastrana was still under his line of authority at the time of the murder. “So our work now is working out who Pastrana was under,” the Commissioner told us.167 Human Rights Watch is concerned that the army’s failure to identify the appropriate unit and commanding officer of a soldier implicated in a serious offense raises the possibility of criminal obstruction.

The reluctance to investigate the involvement of military personnel in killings appears to affect not only local police, but also goes straight to the top of the police. When questioned by the Melo Commission, the PNP Deputy Director General Razon, Jr., admitted that Task Force Usig had never summoned General Palparan, whose possible role in abuses had been frequently raised, for questioning or investigation. General Razon incorrectly claimed that General Palparan was not under the jurisdiction of the PNP.168 General Razon then went on to again incorrectly claim that the PNP was not legally empowered to investigate Major General Palparan in the “absence of evidence.”169 The general counsel of the Melo Commission noted in response that it was the purpose of an investigation to gather evidence. A third incorrect statement made by General Razon before the Melo Commission was that the PNP cannot investigate superior officers of suspected perpetrators if the suspect “remains silent or refuses or fails to point to the involvement of a superior officer.”170 It is the responsibility of the police to conduct appropriate investigations regardless of the intransigence of suspects. Because the legal principle of command responsibility includes liability for both actions and omissions by superior officers, failing to take a prosecution beyond the statements of suspected junior officers will almost certainly hinder efforts to prosecute all those responsible for a crime, regardless of rank.

The AFP has also failed to assist the national Commission on Human Rights in its investigations. Reflecting this, the Commission in August 2006 held Major General Palparan’s 7th Infantry Division in contempt for failing to give adequate answers to the Commission at a hearing on political killings in Central Luzon carried out by the Commission.171

Other civilian oversight bodies have also had difficulty getting co-operation and response from the military. Human Rights Watch spoke with Senator Rodolfo Biazon, the current chair of the Senate Committee on National Defense and Security, and himself a former Chief of Staff of the AFP in 1991. Senator Biazon shared with us letters that he had sent to the AFP in May 2006, requesting the AFP take action in response to allegations the senator had received about human rights violations allegedly perpetrated by elements of the AFP in the province of Bulacan. Almost four months after he sent the request, the senator told us: “[Up] until today, I have yet to receive any feedback from them.”172 Senator Biazon also shared similar concerns about the ability of Congress to provide oversight to those raised later by the Special Rapporteur for Extrajudicial Executions, who cited the executive branch for having “stymied the legislature’s efforts to oversee the execution of laws,” because of its policy that any official requested to appear before the Congress has to seek approval from the President about whether or not they may appear.173

Identification of NPA as perpetrators

The experience here [in Davao City] is every time there is a killing the police float a name and they say the case is closed… we expect the police find the real perpetrators. But it hasn’t happened yet… Usually they float names of members of the NPA.

—NGO representative in Davao City, September 2006

Is there any evidence for this theory [that the NPA are responsible for the spate of extrajudicial executions] that might shake one's certainty regarding the evidence for the military's responsibility? There is not. I repeatedly sought from the military evidence to support these contentions. But the evidence presented by the military is strikingly unconvincing.

—U.N. Special Rapporteur Philip Alston, statement to the U.N. Human Rights Council, Geneva, March 27, 2007

During its 10-week mandate Task Force Usig claimed that it solved 21 cases by filing cases in court against identified suspects, all of them members of the CPP or NPA. The Philippines military continue to assert that extrajudicial killings and “disappearances” are being carried out by the NPA and CPP as part of an internal purge ordered by the CPP founding chair Jose Maria Sison.174 In his testimony before the Melo Commission, PNP Deputy Director General Avelino I. Razon, Jr., claimed that police records indicate that the spate of killings is a result of CPP-NPA “own purging of financial opportunism.”175 However, when asked by Chairman Melo whether the police actually had any data on whom among those killed were financial officers, General Razon could point to only two victims who were allegedly involved in financial operations.176

In most of the cases examined by Human Rights Watch in which the police considered the matter “solved,” the alleged suspects were members of the NPA. In each of these cases, this finding seemed unlikely given the available facts on the ground and consistent rebuttals from the victim’s families. Moreover, experts on the NPA have found no evidence that large-scale intra-NPA killings have persisted beyond the early 1990s, and that the current killings do not reflect the typical pattern of killings by the NPA, thus calling the PNP’s explanation into question.

When Nestor Gonzalez was in the hospital recovering from being shot, local authorities initially told his mother that it was NPA rebels who were responsible. Gonzalez finds this impossible: “The military say it was the NPA who shot me, but I find it unusual because the [local AFP] detachment of the military is just 100 meters away from my house, but they were unable to respond and catch the perpetrators.”177

The police concluded that it was also the NPA who were responsible for killing Sotero Llamas, a former senior NPA commander. Apparently one of the supposed NPA suspects was identified using a police composite artist and, according to the local police superintendent in charge of the case, Nestor Tiempo, “very reliable information, very reliable because the informant was also an NPA, but we only got that information very confidentially.”178 Llamas’ family members dismiss such an idea. When presented with the police’s two alleged suspects, Llamas’ daughter responded: “In our point of view, these are not the killers of my father… The spokesman of the NPA appeared on national TV and said they could not do that to my father after 33 years of dedicated service.”179 The Melo Commission noted that the supposed suspect in the Llamas case was “at best dubious.”180

When asked why the NPA would have issued a denial about its involvement in the killing of Llamas, the police superintendent replied: “That is their opinion of course, they should not claim it. But as far as the result of our investigation, the perpetrators are members of their organization.”181

Llamas’ daughter believes the police have ulterior motives for alleging NPA responsibility: “Because when you conduct an investigation on personnel of the NPA…you can’t do anything because the people aren’t around. You can’t issue them a subpoena, because they won’t show up.”182

The fact that the NPA issued a statement denying involvement in the Llamas killing deserves some credence, as the NPA is typically vocal when it does in fact kill someone. The website of the CCP/NPA, for example, includes press statements in which there are admissions of punishing former cadre, including their murders.183 As Congressman Casiño explained: “Our experience with the NPA is that when they kill—what they call ‘revolutionary justice’—it comes with an explanation and an admission. But in all these cases when the government says [a political killing occurred because of] an internal struggle, there is none of this.”184

When the police identified a person named Dionisio Madanguit as an NPA member responsible for the killings of George and Maricel Vigo, the spokesperson for the NPA’s Magtanggol Roque Command in Southern Mindanao, Ricardo Fermiza, also issued a statement denying that the NPA was responsible for the killings, and that, “There is no Dionisio Madanguit listed in the roster of membership in the NPA.”185

Human Rights Watch spoke with Joel Rocamora, author of “Breaking Through: The Struggle within the Communist Party of the Philippines,” which details in-fighting within the CPP during the 1980s. Rocamora’s book was entered in evidence before the Melo Commission by Armed Forces chief of staff General Esperonto demonstrate that the CPP and NPA kill their own members.186 When asked to compare the anti-infiltration purges of the 1980s with the situation today, Rocamora told Human Rights Watch:

To be sure, the CPP continues to kill people. Not just combatants, but also Party collectors of so-called revolutionary taxes who get suspected of not turning in the money… They continue to kill what they call ‘barrio devils,’ what they call despotic landlords, unrepentant [cattle] rustlers, unrepentant rapists. The NPA runs a system of rough justice in the areas they control… And undoubtedly they still kill a number of their own people who they suspect of being “deep penetration agents” [military informants known as DPAs]. But the anti-infiltration killings were a very specific phenomenon, where… the Party launched mass campaigns against agents, DPAs, and general paranoia. It’s something that has been documented… We know what happened and we know when the last of these campaigns happened. For all intents and purposes, there weren’t any since 1989. The Party is a very large organization, and we would hear about it if there was anything like a major anti-DPA campaign going on.187

Author Bobby Garcia, whose works were also presented as evidence by General Esperon to the Melo Commission, is a former NPA guerrilla who has written on his experiences of interrogation and torture during the anti-infiltration purges of the 1980s. He wrote to us:

While I am not particularly surprised that the military would use the bloody “anti-infiltration operations” done by the CPP-NPA in the 1980s as a powerful propaganda ammunition in their counter-insurgency work, I was nevertheless taken aback when my book was offered as “evidence” against the Communist Party in the recent spate of political killings. My immediate strong reaction is that these issues should never be confused…. [My book] supposedly “supported the military contention that it was the CPP-NPA that were behind the (political) killings” over the past five years. My book was published in 2001, and it chronicled the CPP’s internal violence in the 1980s, under which I myself suffered. It cannot possibly cover events after it was launched, unless I am gifted with prescience. But obviously the logic has to do with establishing a pattern, i.e. the CPP-NPA demonstrated the capacity for brutality before, it is not impossible to imagine that they can still do it now. Perhaps…. [The] problem with all this is that we have a case where the pot and the pan are both calling each other black and greasy. The AFP and the CPP-NPA hold dismal human rights records, thus when one squeaks about violations, the other can easily squawk: “Look who’s talking!” There is a credibility problem here.188

Police identification of unlikely perpetrators

On a scale of one to 10, I think there is a minus one chance of [the police] getting the right person.

—Cousin of victim, Sorsogon, September 2006189

The police have also explained killings by quickly and without evidence attaching blame to organizations besides the NPA with which the victim was involved. Often, these intra-organizational conflicts seem concocted by the police. For example, the attempts by the police to identify a perpetrator in the shooting of Cris Hugo demonstrate how police sometimes appear to be more interested in “solving” a case by quickly identifying someone as their suspect, rather than conducting a serious investigation.

Twenty-year-old Cris Hugo was shot while walking on the streets of downtown Legazpi City, in the province of Albay on March 19, 2006. First, the police suggested that the killing may have been the result of a “frat war” between different social fraternities on campus at Bicol University where Cris Hugo was a student and a member of the Alpha Phi Omega fraternity. Neither Hugo’s mother nor friends who know him find this even remotely plausible. Human Rights Watch spoke with a member of Cris Hugo’s fraternity who denied that any such feud existed. Instead, he noted, “All frats in this region are united. [The only competition we have is] traditional Filipino games competitions, like a band competition, or a literary writing competition. There’s no war.”190 Three days after the shooting, all of the three fraternities on Bicol University campus made statements confirming that there was no such “frat war.”

The local police then suggested that Cris had been shot due to rivalries within the left-wing League of Filipino Students (LFS), an organization of which Cris was regional coordinator. More than a month after the shooting, the police director for Bicol, Chief Superintendant Victor Barbo Boco told a national newspaper:

I was able to talk to the parents of Cris Hugo who confirmed the report that their son had written a formal letter of resignation as a member of the LFS to the organization’s head office in Manila in January this year… [But the LFS did not accept Hugo’s resignation] because he already knew too much.191

Human Rights Watch spoke with Cris Hugo’s mother, who contested this analysis: “[The police] are insisting that, but I do not agree. I know that until the very moment of his death he was still active.”192 She also told us:

[The investigators] are asking [my husband and I] to make some statements about Cris’ activities prior to this crime. I know that their questions will be leading me to make the perpetrators a member of LFS or NPA… Maybe the investigator wants to finish the investigation, so they are asking some affidavits of us. They will throw questions to me. According to them my statements will help the process of the investigation… They present so many angles and stories about Cris’ death. They insinuate stories about Cris’ killings. Even though they are insisting, I do not accept that Cris was killed by a member of LFS, but that is what they are trying to put in the investigation… I don’t believe it because what is the reason? His whole time was dedicated to this organization, he even disregarded his studies a little for the organization, so how could the organization kill Cris?193

A representative from LFS told Human Rights Watch:

We are students. How can we kill someone like Cris? It was a brutal murder. I don’t think a student could kill someone like that. We have no guns… There was no such rivalry in our organization. We, the members, elected Cris as leader of our organization. There was no such rivalries in our organization… Cris was a very kind man, a very loving man, and a kind friend.194

Eight months following the shooting, the police told Cris Hugo’s parents that there is still no new progress in their investigations.

Threats and Harassment of human rights lawyers

Human Rights Watch met with three human rights lawyers who have received death threats and other harassment because of their work with members of leftist civil society groups, which inhibits their ability to provide effective legal counsel to defendants and to press for prosecutions on behalf of victims’ families. Their harassment reflects their persecutors’ view that the work of these lawyers—either in defense of NGO members or in advocating for the rights of victims of abuse—as supportive of the CPP and NPA.

A lawyer working on the case of one activist who was killed, who asked not to be named in our report because of concerns of reprisal for speaking out, related a recent threat: “I received a [piece of] manila paper sent by commercial carrier to my office, addressed to me, saying ‘Death to Supporters of the Communist Party’… After that there were several [threatening] calls that I received to my landline. I consider it serious… My children are now fearing for me.”195

Romy Capulong, a human rights lawyer who was also appointed as a United Nations ad litem Judge for the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, believes that he escaped yet another assassination attempt on June 25, 2006.196 Another lawyer told us how she had become accustomed to being sued for libel when she became involved in human rights cases, or in cases against powerful local political interests, but that she had now started receiving death threats by text message as well.197

Harassment of international human rights workers

I could see on the screen the word “blacklisted” and my name. There was something flashing. I do remember seeing the word blacklisted flashing. It was a bit like in the movies.

—Brian Campbell, American lawyer for International Labor Rights Fund, Washington, D.C., December 2006198

Although President Arroyo has made numerous public announcements welcoming international assistance in investigating unsolved killings in the Philippines, her government’s treatment of international observers at times belie this public commitment.

In response to an Amnesty International report on political killings in the Philippines in August 2006, an association of retired generals—the Association of Generals and Flag Officers—called for the organization to be declared persona non grata and banned from the Philippines. According to the association, whose current ex-officio co-chairman is AFP Chief General Hermogenes Esperon Jr., Amnesty International’s investigators were “obnoxious and undesirable aliens that inflict harm and injury upon the reputation of the Filipino people.”199 In September 2006 President Arroyo visited Amnesty’s International Secretariat in London to publicly and personally invite the organization to assist in the investigation of the political killings. Then in early November 2006 a spokesperson for the AFP, Rear Admiral Amable Tolentino, chief of the Armed Forces Civil Relations Service (CRS), said the AFP agreed with the association of retired generals’ recommendation and also wanted Amnesty International members banned from the Philippines.200

In November 2006 three Canadians—a lawyer, a nurse, and a trade unionist—who had been invited by Karapatan to conduct a fact-finding mission in Quezon province, reported being harassed and detained by the military.201 Ning Alcuaz-Imperial , the lawyer in the group, said that Lieutenant Colonel Bustillos of the 74th Infantry Battalion threatened to charge the group with obstruction of justice if they tried to visit San Pablo, Laguna, south of Manila on November 16.202 According to the trade unionist, Jennifer Efting, the three were prevented by military officials from entering a town south of Manila on November 16, and then taken to a police station. Although they were not charged or put in cells, they were threatened with arrest and kept at the police station for a total of 13 hours on November 16 and 17.203

On December 7, 2006, Brian Campbell, an American lawyer working for the Washington, D.C.-based NGO, the International Labor Rights Fund, was barred from entering the Philippines at the international airport in Manila. Campbell had previously participated in fact-finding investigations on killings in the Philippines, and had helped organize international protests against them. Campbell was traveling again to the Philippines at the request of a number of local NGOs. While being detained in a side room by immigration officials prior to his deportation, Campbell was shown an official list. As he explained:

Then [the immigration official] came back with the blacklist. He said to me “So you were [previously in the Philippines] on an international solidarity mission?” And he asked if there were Taiwanese and Koreans on this mission. And I said “Yes, there were.” Obviously, he was looking through this list and he’s seeing names that were from various other counties… He then showed me the first page of the list. He said, “I’m just trying to understand why your name is on this list. Do you recognize any names on the list?” Then he shows me this list. Then on the top of this list, about seven names down is [an American lawyer, name withheld], then a few lines down [another American lawyer, name withheld]. Then a series of fathers, I presume priests from different churches. And I saw some Chinese and Korean names, but I don’t know if they were people who were on my mission. Immediately I said, “I recognize some of these names because they are also American human rights lawyers.” He put a check on the list next to [name withheld]’s name. But none of these people came to the Philippines with me, they didn’t come on the mission with me… By that point I was aware that the criteria for inclusion on this list: participation in a fact-finding mission of some sort, and investigations into these political killings.204

Human Rights Watch contacted the Philippines Embassy to the United States to request a copy of this blacklist. The embassy informed us that the blacklist had been developed to ensure security during the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) summit meeting being held in the Philippines in December 2006. In January 2007 the embassy assured Human Rights Watch that the blacklist had now been lifted, and had only been in effect for the summit. The embassy would not explain to us, however, why the identified human rights lawyers were considered a security threat, but suggested that the list had been developed in consultation with the Philippines domestic intelligence agencies and in cooperation with other similar agencies in ASEAN and other countries.205 The embassy could also not confirm how many names were on the blacklist. When shown the blacklist by the immigration officer, Campbell recalled:

It was an A4 sheet of paper, [maybe] 14 point font… The writing started about six inches down, one name per line, so I don’t know what that works out to be. That’s probably about 40 lines a page, and about three or four pages of names. I’m speculating that all pages had names, but I know for sure that two pages had names.206

101 Human Rights Watch interview with Father Jovic Lobrigo, September 19, 2006.

102 Lieutenant Colonel Bartolome V. O. Bacarrio, “Status of AFP Members Implicated in Unexplained Killings,” Armed Forces of the Philippines press release, March 17, 2007.

103 Lieutenant Colonel Bartolome V. O. Bacarrio, “Status of AFP Members Implicated in Unexplained Killings,” Armed Forces of the Philippines press release, March 17, 2007.

104 “Preliminary note on the visit of the Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions, Philip Alston,

to the Philippines (12-21 February 2007),” A/HRC/4/20/Add.3, March 22, 2007, p. 4.

105 “Preliminary note on the visit of the Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions, Philip Alston,

to the Philippines (12-21 February 2007),” A/HRC/4/20/Add.3, March 22, 2007, p. 5.

106 Command responsibility has been defined as when a commander or other superior knew or should have known that subordinates were committing or about to commit crimes and failed to take all necessary and reasonable measures to prevent them or to punish the persons responsible. See, for example, Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, 2187 U.N.T.S. 90, entered into force July 1, 2002, article 28.

107 General Hermogenes Esperon Jr., quoted in Christine Avendaño, Dona Pazzibugan, “Arroyo to seek Europe help in probing slays,” Philippine Daily Inquirer, January 31, 2007.

108 AFP Chief of Staff, General Hermogenes Esperon, Jr., paraphrased in Melo Commission Report, p. 17.

109 AFP Chief of Staff, General Hermogenes Esperon, Jr., paraphrased in Melo Commission Report, p. 17.

110 PNP Deputy Director General Avelino I. Razon, Jr., paraphrased in Melo Commission Report, p. 9.

111 See generally, Draft Articles on the Responsibility of States for Internationally Wrongful Acts, Report of the ILC on the Work of its Fifty-third Session, UN GAOR, 56th Sess, Supp No 10, p 43, UN Doc A/56/10 (2001).

112 See Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and relating to the Protection of Victims of International Armed Conflicts (Protocol I), Art. 86 (many provisions of Protocol I are recognized as reflective of customary international law).

113 Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and relating to the Protection of Victims of Non-International Armed Conflicts (Protocol II), Art. 19.

114 Melo Commission Report, p. 53.

115 Melo Commission Report, p. 59.

116 Melo Commission Report, p. 61.

117 Testimony by PNP Deputy Director General Avelino I. Razon, Jr. to the Melo Commission, noted in Melo Commission Report.

118 Human Rights Watch interview with MaribelAlave, September 15, 2006.

119 Human Rights Watch interview with Marianita Vigo, September 15, 2006; and Human Rights Watch interview with Norma Alave, September 15, 2006.

120 Human Rights Watch interview with Glenda M. Gloria, Managing Editor, Newsbreak, September 12, 2006.

123 Human Rights Watch interview with Sonia Santa Rosa, September 20, 2006.

124 Human Rights Watch interview with Maria Fabicon (not her real name), date withheld, 2006.

125 Investigation Report, July 20, 2006, Casiguran Municipal Police Station.

126 Human Rights Watch interview with Ian Hagosojos, September 21, 2006.

127 Human Rights Watch interview with Ian Hagosojos, September 21, 2006.

128 Human Rights Watch interview with Arnel Guran, September 21, 2006.

129 Mello Commission Report, pp 43-44; Manila Times, “’Breakthrough’ in Llamas’s murder a dud,” October 6, 2006.

130 P/Supt Nestor Y. Tiempo v. Edgardo Sevilla, et al, I.S. No. T-2006-104, Joint Resolution, City Prosecution Office, Tabaco City, September 4, 2006, pp. 17-18. The notes read: “The hearing was scheduled on August 8, 2006 but no clarificatory [sic] inquiry was had on that date regarding the merit of the case, the declarations of the witnesses and the evidence because the respondents [i.e. the two accused individuals] cannot and have not been subpoenaed since they cannot be found in the given addresses. This is aside from the fact that the addresses are incomplete, in the first place. That hearing day allotted for clarificatory inquiry has to be utilized instead by the investigating prosecutor to still seek confirmation from P/Supt Tiempo and his witness (P/CInsp Berdin) whether the given addresses were really that of the respondents, to which they replied with apparent and initial hesitance that [the village of] Jovellar is that of Edgar Calag while [the village of] Lion is Edgardo Sevilla’s but [the village of] Tiwi is a place where he was previously sighted and expected to visit. When queried further as the correct and complete family residences of the respondents, said police officers have difficulty giving them for several minutes; but at last they were able to do so after conferring with each other and by supposedly contacting thru cellular phone their colleagues while the hearing was going on… A new set of subpoenas including the complaints and appendages were again tried to be served to the respondents in their supposed complete addresses.”

131 Memorandum: Written Report on Shooting to Death of Spouses George and Maricel Vigo, Kidapawan City Police Station, June 06 [sic], 2006.

132 Sworn statement to police of Pampilo Alvendia Dela Cruz, Jr., June 24. Copy on file with Human Rights Watch.

133 Sworn statement to police of Iremeo Tiemsen Rabino, June 23, 2006. Copy on file with Human Rights Watch.

134 Sworn statement to police of Joseph Ferolino Tabano, June 22, 2006. Copy on file with Human Rights Watch.

135 Human Rights Watch interview with Norma Alave, September 15, 2006.

136 Human Rights Watch interview with Roderick Abalde, September 15, 2006.

137 Human Rights Watch interview with Marilyn Llamas, September 21, 2006.

138 Translations of text messages kept in log by Marilyn Llamas. According to her log, these texts were received respectively on August 26, 2006, at 7:21 a.m., August 23, 2006, at 4:02 p.m., and August 26, 2006, at 3:38 p.m.

139 Human Rights Watch interview with Reverend Marielou “Malou” Lumayad Tinambacan, November2006.

140 Human Rights Watch interview with Norma Alave, September 15, 2006.

141 Human Rights Watch interview with GregorioAlave, September 15, 2006.

142 Human Rights Watch interview with Ray-Sun Santa Rosa, September 20, 2006.

143 Human Rights Watch interview with Conrado Alarilla, Jose Gomez, and Joey Castillo (not their real names), October 14, 2006.

144 Human Rights Watch interview with Ian Joel Guran, September 21, 2006; Human Rights Watch interview with Ian Hagosojos, September 21, 2006.

145 Human Rights Watch interview with Ian Hagosojos, September 21, 2006.

146 Bishop Eliezer Pascua, General Secretary of the United Church of Christ in the Philippines, statement to the United States Senate Sub-Committee on East Asian and Pacific Affairs, March 14, 2007.

147 Witness Protection, Security and Benefit Act, Republic Act No. 6981, April 24, 1991.

148 Witness Protection, Security and Benefit Act, Republic Act No. 6981, April 24, 1991, section 3.

149 Human Rights Watch interview with Romy Capulong, attorney, September 23, 2006.

150 Human Rights Watch with Jose Lipa Capinpin, Chief of Police Daraga, September 22,2006.

151 Lieutenant Colonel Bartolome V. O. Bacarrio, “Status of AFP Members Implicated in Unexplained Killings,” Armed Forces of the Philippines press release, March 17, 2007.

152 People of the Philippines v. Bismanos, Cagayag, Barua, Grecia, Montañer, and Sabay, decision, 7th Judicial Region, Branch 21 Cebu City, Criminal Case No. CBU-75556, September 28, 2006.

153 Human Rights Watch interview with Belen Santos, September 21, 2006.

154 Human Rights Watch interview with Attorney Roberto Orlanda (not his real name), date withheld, 2006.

155 Human Rights Watch interview with Marilyn Llamas, September 21, 2006.

156 Human Rights Watch interview with Maria Balani (not her real name), date withheld, 2006.

157 Human Rights Watch interview with Maria Fabicon (not her real name), date withheld, 2006.

158 Human Rights Watch interview with Governor Josefina “Josie” Mendoza Dela Cruz, September 13, 2006.

159 Human Rights Watch interview with Governor Josefina “Josie” Mendoza Dela Cruz, September 13, 2006.

160 Human Rights Watch interview with Governor Josefina “Josie” Mendoza Dela Cruz, September 13, 2006.

161 Human Rights Watch interview with Jocelyn Javier, October 27, 2006.

162 Human Rights Watch interview with Ian Joel Guran,September 21, 2006.

163 Human Rights Watch interview with Ian Joel Guran,September 21, 2006.

164 Human Rights Watch interview with Joseph Gonzalez (not his real name), date omitted, 2006.

165 Human Rights Watch interview with Jose Lipa Capinpin, Chief of Police Daraga, September 22,2006.

166 Human Rights Watch interview with Jose Lipa Capinpin, Chief of Police, Daraga, September 22, 2006.

167 Human Rights Watch interview with Pelagio Señar, Regional Human Rights Director, Philippines Commission on Human Rights, Legazpi City, Regional Office V, September 20, 2006.

168 PNP Deputy Director General Avelino I. Razon, Jr., paraphrased in Melo Commission Report, p. 9. AFP Chief of Staff General Hermogenes Esperon later conceded before the Commission that the PNP is indeed entitled to proceed with criminal investigations against members of the military; paraphrased in Melo Commission Report, p. 15.

169 PNP Deputy Director General Avelino I. Razon, Jr., paraphrased in Melo Commission Report, p. 9.

170 PNP Deputy Director General Avelino I. Razon, Jr., paraphrased in Melo Commission Report, p. 9.

171 “CHR Holds Palparan Army Unit in Contempt for Snub of Probe,” Philippine Daily Inquirer, August 26, 2006.

172 Human Rights Watch interview with Senator Rodolgo Biazon, Senate Office, September 13, 2006.

173 “Preliminary note on the visit of the Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions, Philip Alston,

to the Philippines (12-21 February 2007),” A/HRC/4/20/Add.3, March 22, 2007, p. 5.

174 See, for example, statement by Captain Lowen Marquez, Civil Relations Service of the AFP in Western Visayas, in Nestor P. Burgos, Jr., “Ilonggo folk shocked over abduction,” Philippine Daily Inquirer, April 21, 2007.

175 Philippines National Police Deputy Director General Avelino I. Razon, Jr., quoted in the Melo Commission report.

176 Melo Commission Report, p. 9.

177 Human Rights Watch interview with Nestor Gonzalez (not his real name), date omitted, 2006.

178 Human Rights Watch interview with Nestor Tiempo, Police Superintendent, CDIG, Camp Simeon A Ola, Legazpi City, September 21, 2006.

179 Human Rights Watch interview with Marilyn Llamas, September 21, 2006.

180 Melo Commission report, p. 41.

181 Human Rights Watch interview with Nestor Tiempo, Police Superintendent, CDIG, Camp Simeon A Ola, Legazpi City, September 21, 2006.

182 Human Rights Watch interview with Marilyn Llamas, September 21, 2006.

183 For example: Rafael De La Cruz, Wilfredo Zapanta Command, Front 18 Operations Command, Southern Mindanao, “Enemy Intelligence Agent Punished,” February 14, 2006.

184 Human Rights Watch interview with Representative Teodoro A. Casiño, Party-List Representative for Bayan Muna, National House of Representatives, September 12, 2006.

185 Ricardo Fermiza, “Murder of Couple is the Handiwork of AFP Death Squads,” public statement, June 23, 2006, available at http://www.philippinerevolution.net.

186 James Mananghaya, “843 civilians, 384 soldiers and cops killed by NPAs — Esperon,” The Philippine Star, September 19, 2006; Fe Zamora, “Reds killed over 1,200, Esperon testifies,” Inquirer, September 19, 2006.

187 Human Rights Watch interview with Joel Rocamora, September 26, 2006.

188 Robert Francis Garcia, email to Human Rights Watch, October 16, 2006.

189 Human Rights Watch interview with Ian Joel Guran, September 21, 2006.

190 Human Rights Watch interview with Daven Tarog, September 19, 2006.

191 Chief Superintendant Victor Barbo Boco, quoted in Celso Amo, “Camarines Norte Head of Bayan Muna Slain,” The Star, April 28, 2006.

192 Human Rights Watch interview with Rowena Hugo, September 21, 2006.

193 Human Rights Watch interview with Rowena Hugo, September 21, 2006.

194 Human Rights Watch interview with Lessa Lopez, September 19, 2006.

195 Human Rights Watch interview with Attorney Roberto Orlanda (not his real name), date withheld, 2006.

196 Human Rights Watch interview with Romy Capulong, attorney, September 23, 2006; National Lawyers Guild, “Philippines: The NLG condemns the killings of members of the legal profession in the Philippines,” press release, August 7, 2006.

197 Human Rights Watch interview with Maria Fiel (not her real name), attorney, date withheld, 2006.

198 Human Rights Watch interview with Brian Campbell, December 12, 2006.

199 Aris R. Ilagan, “AFGO calls Amnesty Int’l report unfair,” The Manila Bulletin Online, August 19, 2006.

200 Joel Guinto, “AFP backs ex-generals’ ‘persona non grata’ tag on Amnesty,” Philippine Daily Inquirer, November 14, 2006.

201 Carlos H. Conde, “3 Canadian activists say Philippines military harassed them,” November 19, 2006.

202 http:www.pcij.org/blog/?p=1323, accessed May 30, 2007.

203 http://www.straight.com/article/soldiers-held-local-activists, accessed May 30, 2007.

204 Human Rights Watch interview with Brian Campbell, December 12, 2006.

205 Human Rights Watch interview with Gines Gallaga, January 29, 2007.

206 Human Rights Watch interview with Brian Campbell, December 12, 2006.