(New York) - Pursuing justice against abusive leaders is too often undervalued as negotiators and officials weigh competing objectives in resolving armed conflicts, Human Rights Watch said in a report released today.

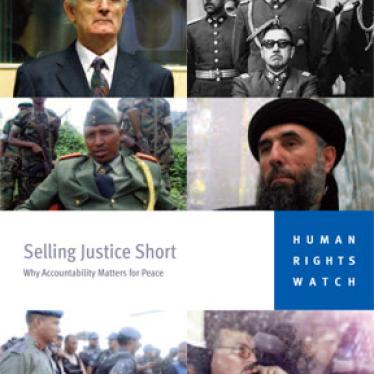

The 128-page report, "Selling Justice Short: Why Accountability Matters for Peace," draws upon Human Rights Watch's work over the past 20 years in nearly 20 countries. The report documents how ignoring atrocities reinforces a culture of impunity that encourages future abuses. Rather than impede negotiations or a transition to peace, remaining firm on justice can yield short- and long-term benefits. Anticipated negative consequences of pressing for accountability often do not come to pass. Justice is also important as a matter of principle. Fair trials may assist in restoring dignity to victims by acknowledging their suffering.

"The conventional wisdom that pursuing justice in the midst of a conflict will undercut chances at peace has not proven true," said Sara Darehshori, senior counsel in Human Rights Watch's International Justice Program and author of the report. "The sky has not fallen. In fact, an indictment may move negotiations forward by marginalizing and stigmatizing an abusive leader."

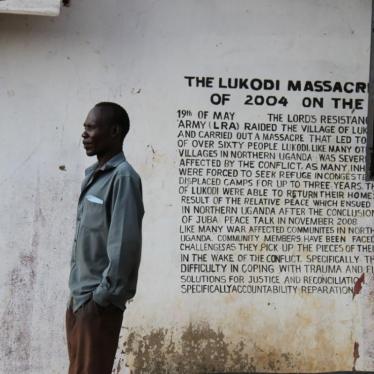

The report examines the prosecutions of Liberia's Charles Taylor, Serbia's Slobodan Milosevic, and Uganda's rebel Lord's Resistance Army. "Selling Justice Short" shows that their indictments did not have the predicted negative impact on peace talks. Nor did the anticipated damage to Chile's democratic transition occur after former leader Augusto Pinochet was arrested in the United Kingdom.

At the same time, Human Rights Watch research shows that the decision to overlook serious international crimes, and to include those implicated in human rights abuses in the government in an effort to consolidate peace, often has unwelcome repercussions.

"Turning a blind eye to crimes and offering abusive leaders official positions may cause unforeseen harm," said Darehshori. "Rather than creating stability, allowing criminal suspects into the government can result in further violations that erode people's faith in a new regime."

The report looks at the lessons of Afghanistan, where giving official positions to those with blood on their hands has resulted in more violence. This has delegitimized the government with many Afghans. In the Democratic Republic of Congo, the effort to end conflict by giving people with records of past abuse posts of responsibility in the army has resulted in the proliferation of rebel groups that see no downside to taking up arms. In Bosnia and Herzegovina, keeping those involved in "ethnic cleansing" in official positions following the 1995 Dayton agreement slowed early implementation of the peace accord.

The report also examines the effects of amnesties or a decision not to prosecute in Sierra Leone, Angola, and Sudan and finds that a decision to forgo accountability did not achieve the hoped-for benefit of peace.

"All too often, a peace that is premised on amnesty is not sustainable," said Darehshori. "Worse, it may set the stage for further abuses."

Decisions to forego accountability can also create an atmosphere of distrust and revenge that may later be manipulated by leaders seeking to foment violence for their own political ends.

The report examines long-term benefits of justice including promoting prosecutions in national courts, contributing to a record of the crimes, and providing some short-term deterrent effects. While many factors undoubtedly influence the resumption of armed conflict, and Human Rights Watch does not assert that the failure to bring abusers to justice is the sole factor, the potential impact of justice is frequently underestimated when weighing competing factors in resolving a conflict.

"When people are under pressure to negotiate a peace deal, justice may seem like a dispensable luxury," said Darehshori. "However, experience shows that any decision to forego accountability may prove costly in terms of lives and long-term stability."