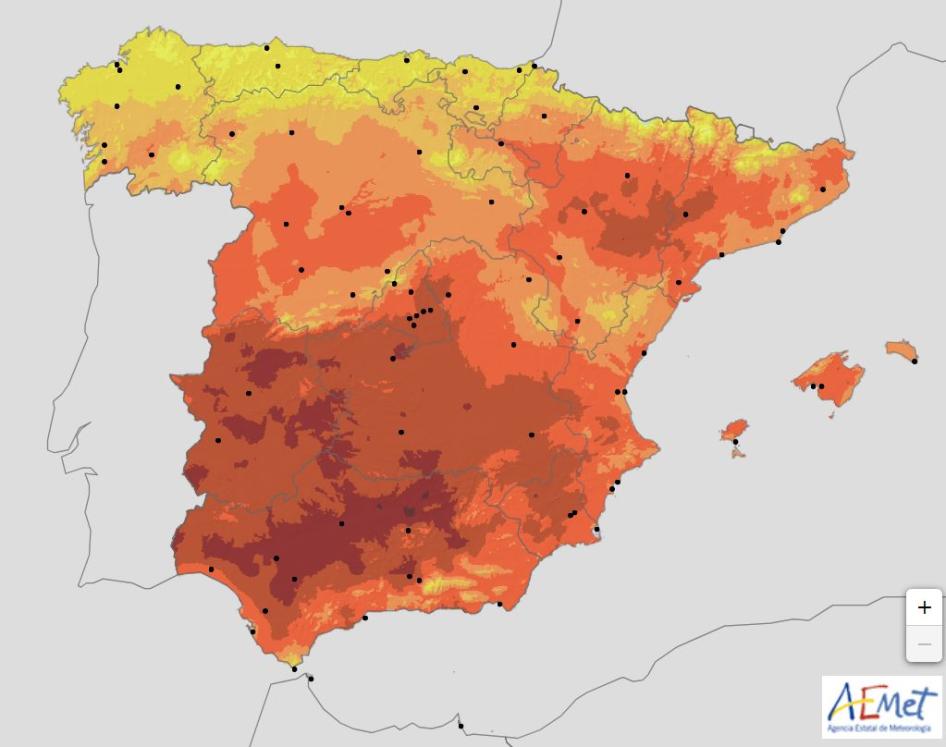

- Extreme heat fueled by climate change and inadequate government response caused great hardship for people with disabilities during the 2022 heatwaves in Spain, a study focusing on Andalusia shows.

- People with disabilities are often among those most adversely affected in an emergency, including a heatwave, yet least able to access support.

- With more intense and frequent heatwaves looming, authorities should learn from last year’s shortcomings and involve people with disabilities in developing a climate action plan.

(Brussels) – Extreme heat fueled by climate change and inadequate government response cause severe hardship and distress for people with disabilities, Human Rights Watch said today based on a study of the response in the summer of 2022 in Andalusia, Spain.

More people face the risk of heat stress and even death as average temperatures increase across the world, with more heatwaves predicted for Southern Europe, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). People with disabilities are often among those most adversely affected in an emergency, including a heatwave, yet least able to access support. Such disproportionate impacts are a result of a host of factors, including lack of inclusion in emergency and adaptation planning, inadequate emergency communication, accessibility issues, isolation, and economic marginalization.

“People with disabilities are at high risk of harm from exposure to extreme heat, including risk of death and physical, social, and mental health distress, especially when they are left to cope with dangerous temperatures on their own,” said Jonas Bull, assistant disability rights researcher at Human Rights Watch. “With more intense and frequent heatwaves looming, authorities in Andalusia should learn from last year’s shortcomings and involve people with disabilities in developing an inclusive climate action and heatwave response plan.”

Between June and August 2022, many European countries, including Spain, experienced record-breaking heatwaves. No data exists on how many people with disabilities died because of extreme temperatures. According to the Carlos III Health Institute, the primary Spanish governmental agency for health statistics, mortality data related to extreme temperatures is not collected on the basis of disability. Government data is, however, disaggregated by age and indicates that more than 98 percent of around 4,600 heat-related mortalities in Spain in that period were people aged 65 and older. This would have included many people with disabilities since more than half of the people with disabilities registered in Spain are 65 and older.

Human Rights Watch interviewed 33 people with disabilities in the cities of Seville and Córdoba, and nearby areas in Andalusia. Seville and Córdoba, like several of Andalusia’s big cities, are prone to and have experienced “urban heat island effects” that increase temperatures in urban environments.

Most people with disabilities interviewed said that the 2022 heatwaves had a serious negative impact on their physical health. They described brain fog, difficulties breathing, low blood pressure, dizziness, weakness, sleep deprivation, water retention, infections, and losing consciousness. Most said the heatwaves affected their mental health too. They also described loneliness and the social isolation they feel is amplified during extreme heat when they are compelled to stay at home for long periods. Several studies found that people with disabilities experience loneliness and social isolation at higher rates than people without disabilities. Social isolation is associated with higher heat risks, including for mortality.

The 2022 Andalusian Heatwave Action Plan (Plan Andaluz para la Prevención de los Efectos de las Temperaturas Excesivas sobre la Salud) does not explicitly recognize people with disabilities as a group more susceptible to the negative effects of extreme heat or define specific actions except for those living in institutions. Similarly, while the 2022 Spanish National Heatwave Action Plan (Plan Nacional de Actuaciones Preventivas de los Efectos del Exceso de Temperaturas sobre la Salud) mentions disability as a “risk factor,” it does not formulate specific actions required to address those risks.

As far as Human Rights Watch has been able to determine, people with disabilities or organizations representing them were not involved in developing the Andalusian heatwave action plan. Consulting people with disabilities would have helped ensure that their rights are realized during a heatwave and reduced avoidable suffering, Human Rights Watch said.

All people with disabilities interviewed said they felt neglected by the local authorities. “I feel abandoned by the government,” said Laura Sanchez, a 41-year-old woman with a physical disability from Seville.

In August 2022, Andalusian authorities said they contacted 12,000 people by phone and conducted some home visits to ensure the safety and protection of people most at risk, including older people and people with mental health conditions. However, none of those interviewed said they had been contacted by any government agencies about how they were coping. They said they felt excluded because the general information on heatwaves and extreme heat provided online and in the media did not address their specific rights and needs. The Andalusian Ministry of Health told Human Rights Watch that it does not have data on how many of the 12,000 people contacted have disabilities.

City authorities in Seville and Córdoba piloted the daytime use of cooling centers in 2022 to support those most at risk, but city officials said the centers were underutilized. Studies suggested that cooling centers’ effectiveness relies on multiple factors, including accessible information and infrastructure. Cities should develop all initiatives to reduce urban heat in consultation with those most at risk to the negative effects of extreme heat and climate change, Human Rights Watch said.

Important heatwave-related information was generally inaccessible. The Andalusian Ministry of Health, city officials in both Seville and Córdoba, as well as a member of the proMeteo Seville Project, a coalition that raises awareness of heatwaves’ health impacts, all acknowledged that, in 2022, heatwave-related information, including general recommendations on protection, was not provided in formats accessible to people with disabilities, such as sign language or Easy-to-Read formats.

Poverty is another risk factor, exacerbating heat and related impacts for many residents of Andalusia, one of the poorest autonomous communities in Spain. According to research and environmental activists in Andalusia, many residents experiencing poverty live in buildings with poor insulation and a lack of green space, both of which contribute to heat-related health risks. Power cuts in Andalusia’s poorer neighborhoods may further and severely affect people with disabilities because they may not be able to use elevators, charge disability-related devices, or stay cool with electric fans or air-conditioning.

Maria C. (a pseudonym), 66, has a disability, lives in a poorer neighborhood of Seville, and has trouble paying her electricity bill. In July 2022, the hottest month ever recorded in Spain, her electricity was shut off. “In that week, it was really bad,” she said. “I didn’t open the fridge because I did not want the fruit to go bad, I could not use ice to stay cool, and I could not use the bedroom fan.” The power cut occurred even though Spain’s National Strategy against Energy Poverty 2019-2024 (Estrategia Nacional contra la Pobreza Energética) prohibits the interruption of energy supply for any reason during extreme temperatures.

Under international human rights law, including the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), Spain and its autonomous communities must ensure the protection and safety of people with disabilities during natural disasters and protect them from reasonably foreseeable threats to life, including from climate change. Furthermore, governments have an obligation to protect and promote the human rights of people with disabilities in all policies and programs, including government responses to extreme weather events.

The authorities should thoroughly investigate and monitor the impacts of extreme weather events exacerbated by climate change, such as heatwaves, and disaggregate data by age, disability, and other factors, Human Rights Watch said.

“Andalusian authorities should recognize extreme heat as a core threat to its population and people with disabilities as a group more at risk to extreme heat,” Bull said. “If inadequately handled, as happened during the 2022 heatwaves, without developing specific actions to protect people with disabilities, they will continue to disproportionately bear the brunt of the climate crisis.”

Methodology

Between March and April 2023, Human Rights Watch interviewed 33 people with disabilities, including 3 older people and 2 children; 23 representatives of disability rights organizations, environmental groups, climate activists, and other civil society groups; 3 university researchers; and 1 psychiatrist. Human Rights Watch also met with government officials at national, regional, and local level.

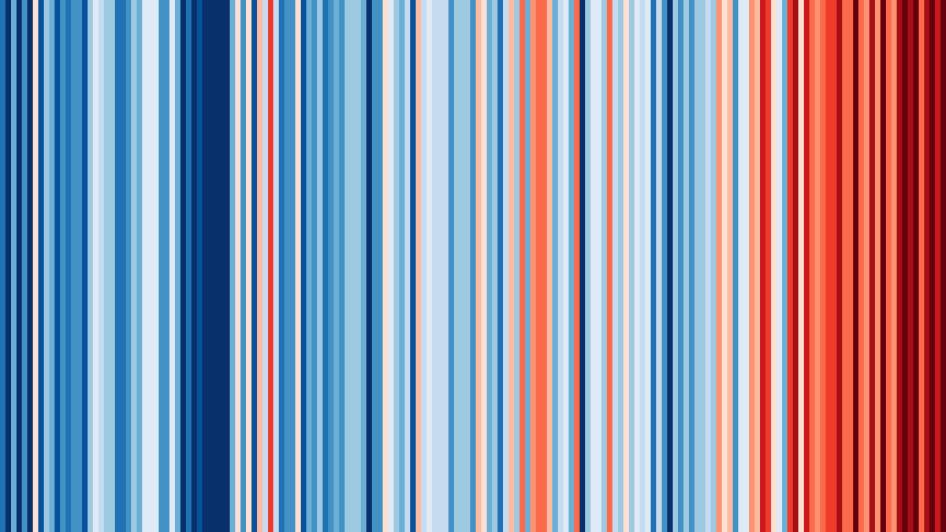

Climate Adaptation Plans and Actions Responding to the Extreme Heat

Extreme events, including heatwaves, have already intensified and will continue to increase in frequency and intensity because of climate change. Climate scientists have confirmed a rise in mean temperature and extreme heat in Southern Europe, including Spain. Even if greenhouse gas emissions were reduced quickly, Andalusia is expected to face progressive temperature increases. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change predicts that, based on governments’ current commitments to reduce emissions, global warming will exceed 1.5 degrees Celsius relative to 1850-1900 in the first half of the 2030s, and possibly as early as the 2020s, if global emissions remain very high.

In these scenarios, some of Europe’s strongest hot weather extremes are projected to occur in Southern Europe, including Spain. In 2021, Spain was the fifth largest emitter in the European Union (EU) and emissions had increased compared to 2020. The EU aims to be climate neutral by 2050 and reduce emissions by 55 percent by 2030 from 1990 levels.

Spain and Andalusia have adopted plans to address the general impacts of climate change, but they do not sufficiently address the rights and needs of people with disabilities. The National Climate Change Adaptation Plan 2021-2030 (Plan Nacional de Adaptación al Cambio Climatico), Spain’s primary policy to “promote coordinated and coherent action to tackle the effects of climate change in Spain,” only addresses the rights of people with disabilities when citing the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change and its encouragement to make use of stakeholder input, including from people with disabilities.

While the plan lists actions to protect “vulnerable” populations, it does not propose any specific measures to ensure the protection and safety of people with disabilities. Similarly, the Andalusian Climate Action Plan 2021-2030 (Plan Andaluz de Acción por el Clima) does not mention the rights of people with disabilities, although it does make a general reference to “vulnerable groups.”

In 2022, Spain and its autonomous communities, which have major public health competencies, created plans to adapt to heatwaves. The Andalusian Heatwave Action Plan, activated every summer from June to September, aims to protect groups it considers to be at particular risk, such as people over 65, people with medical conditions, and people living in residential institutions, including shelters for unhoused people.

People with disabilities more generally are not covered, though, except those living in institutions. The Andalusian Health Ministry told Human Rights Watch that while people with disabilities are not specifically mentioned in the plan, they would be included in the response along with other people considered to belong to vulnerable groups.

The plan lays out preventive measures, such as sharing information through social media on how people can protect themselves, and concrete activities for three heat alert levels depending on the severity of the heat. It also aims to proactively identify people considered at particular risk. And if a heatwave is projected to last five days or longer, local public bodies are required to contact people considered at particular risk and offer them the option of spending the day at a cooling center.

The National Adaptation Plan recognizes the mental health impacts of extreme weather events. However, this plan and Andalusia’s heatwave action plan have no mention of concrete activities to support people’s mental health during heatwaves, such as offering psychosocial support or initiatives to specifically protect people with existing mental health conditions. Furthermore, the National Mental Health Strategy 2022-2026 does not mention the mental health impact of heatwaves specifically or climate change more generally.

Physical Health Impact

Studies show that people with disabilities are at particular risk of heat-related illness and death. Some are more likely to have health conditions that can affect the body's ability to respond to heat while others may face social isolation which is associated with higher heat risks. Not being included in the government heatwave response and facing barriers in accessing support increases these risks. Human Rights Watch interviewed people with various disabilities, including intellectual, physical, and psychosocial disabilities, to capture a range of perspectives. Most said heatwaves significantly affected their physical health and expressed fear of higher health risks with increasing temperatures.

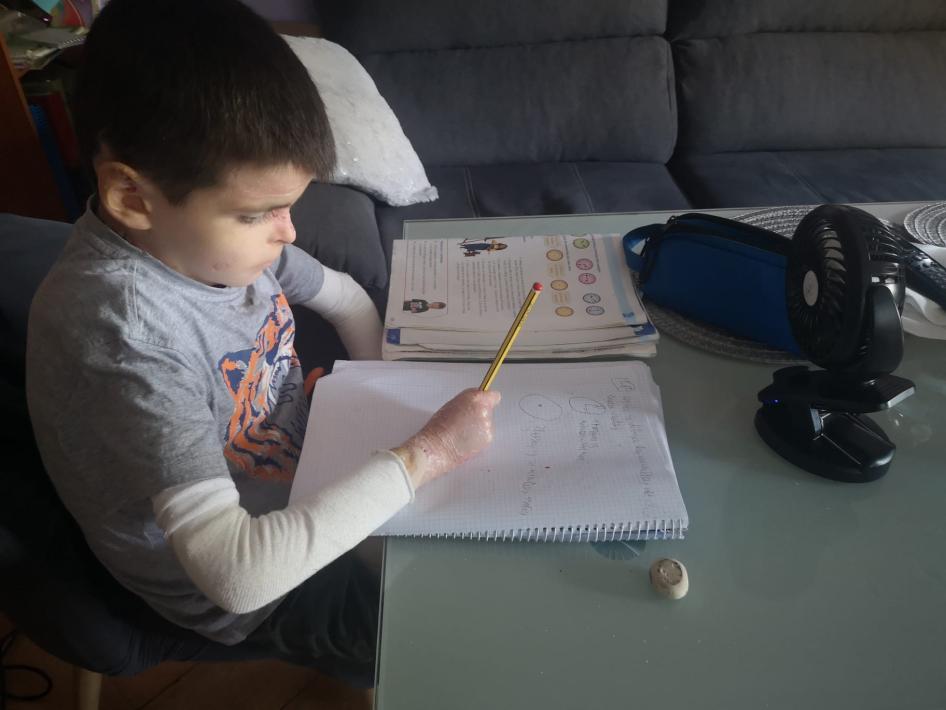

Leo Osorio, 9, lives on the outskirts of Seville with his parents and brother, Abraham, 13, who has autism. Leo has epidermolysis bullosa (EB), or butterfly skin condition, a rare genetic condition that increases the fragility of the skin, which can blister at the slightest touch. In 2022, he stayed at home in July and August. He said: “I always had to have the air conditioning on because I get affected by heat, and all my injuries get worse.”

His mother, Lidia Osorio, said she had to spray Leo with mineral water to keep his skin moist. She believes the government had forgotten about them since they did not receive specific information on how to protect themselves during heatwaves and no heat-related services reached them. She fears this year’s heatwave will be worse than the last.

Juan Manuel Ramírez Montesinos, 47, has a physical disability and lives in an apartment in Seville. He wants more adequate health support for generally coping with extreme heat, not only for emergencies. He described an experience when the temperature rose above 40 degrees Celsius:

My body changes a lot every 2 to 3 degrees, and high temperatures really affect me. Extreme heat makes me have low blood pressure. My main issue with heat is fluid retention, and my feet and legs swell, so I cannot go outside.

Esther la Forge, 34, who has a physical disability and lives outside Seville, said:

Last summer, I suffered a lot in the heat…. I need to cool down my body, it’s like having a strong fever all the time. It’s like [my] body asks for more energy that I don’t have until I collapse.

Human Rights Watch interviewed six people with psychosocial disabilities who take psychotropic medication and struggled to cope. People with psychosocial disabilities are at higher risk of death during heatwaves, including due to difficulties regulating their body temperature as well as stigmatization and social exclusion, which may limit their access to support networks.

Marta H. (a pseudonym), who has a psychosocial disability, has low blood pressure, and lives in Seville, said:

I remind myself that I have to minimize medication [intake] because of heatwaves. I know my symptoms, and when I feel bad, I know how to treat myself. But there are [other] people with mental health conditions who do not recognize the symptoms and may overmedicate.

None of the people with disabilities interviewed had received medical advice on how to cope with heatwaves. Human Rights Watch spoke with a psychiatrist from Seville who believes medical professionals are insufficiently informed about the risks faced by people with psychosocial disabilities during extreme heat. He, and all people with disabilities interviewed, said that general recommendations on protections broadcasted through traditional or social media did not contain any specific advice either.

Mental Health Impact

Almost all people with disabilities interviewed said they felt emotionally overwhelmed during the heatwaves, describing the negative mental health impact of protection measures and the absence of targeted initiatives. They mentioned feeling depressed, resigned, anxious, and agitated; one person said she struggled with suicidal thoughts. This aligns with studies suggesting an increase in suicide risk and mental health-related hospital admissions during high temperatures.

Carla S. (a pseudonym), 74, who has a psychosocial disability and lives in Córdoba, said: “When it gets hot, I have anxiety and feel irritable. In those stages, you feel like you want to kill yourself.”

One common recommendation made by local, regional, and national authorities is to remain cool, including by avoiding going outside during daytime. While these measures may save lives, people with disabilities expressed feelings of isolation and loneliness when sheltering alone at home for a prolonged period. This is a particularly concerning finding given rising temperatures, the growing likelihood of heatwaves due to climate change, and the exclusion of mental health support from heatwave action plans. The authorities should intensify efforts to support people with disabilities who are sheltering at home, such as with more targeted outreach services.

“If it’s too hot, I don’t see friends,” said Blanca, 25, who has an intellectual disability and lives in an apartment in Córdoba. “I feel overwhelmed during heatwaves. I really feel locked up.”

Marta H. also described the “vicious circle” created by heatwaves: “Apathy makes you stay all day at home, lying on the sofa and then feeling tired, depressed, not wanting to get out, and [it’s a] never-ending issue.”

Raúl Rodríguez Camacho, 53, has a psychosocial disability and lives with his parents, who are 81 and 91, in an apartment in Seville. To avoid the summer heat, his parents stay in a house near the sea while Raúl stays in Seville for his job. He said:

I am depressed when my parents go to the coast. I feel extremely nervous with life and work, and my stress is worse during heatwaves…. All my life problems are more difficult for me to cope with during heatwaves.

Experiences of Poverty

Access to energy is critical for people with disabilities during extreme heat, not only to stay cool but also, for example, to run assistive devices. Studies suggested that over one-third of people with disabilities in Spain are at risk of poverty and exclusion, which could dramatically increase their risks during extreme heat. This is particularly concerning in Andalusia, which has one of the highest poverty rates among the autonomous communities, households with energy bills higher than the national average due to poor insulation and extreme climate conditions in summer and winter, and about 1 million people facing energy poverty.

Spain defines energy poverty as a situation in which a household cannot meet the basic needs for energy supplies as a result of an insufficient income level and, where appropriate, energy-inefficient housing. Research found that energy poverty can increase health risks during heatwaves.

People who cannot afford to pay their electricity bill can apply for extra state support. Spain’s social tariff for electricity, bono social de electricidad, covers a certain percentage of the electricity bill based on the household’s degree of “vulnerability.” However, this amount may be insufficient. Facing the extreme heat, Lidia Osorio said her family can only afford to use the air-conditioning in Leo’s room at night, despite receiving the social bonus to pay for electricity bills.

Representatives of nongovernmental groups and university researchers said that people in Spain experiencing poverty often live in neighborhoods with poorly insulated buildings and a lack of trees and parks, all of which contribute to the risks of extreme heat. A coordinator of a religious charity supporting people in an economically marginalized neighborhood of Seville said its residents have small apartments with thin walls and small windows that are not energy efficient, and many cannot pay their electricity bill.

Economic marginalization and income insecurity can also affect people’s ability to cope with the heatwaves. Maria (a pseudonym) lives in a poorer part of Seville previously affected by power cuts. She received an air conditioning unit from a religious charity at the end of the 2022 summer but worries she cannot afford to use it: “We’re killing the Earth,” she said. “I am desperate, I don’t know what to do.”

During the 2022 heatwaves, several low-income neighborhoods experienced power outages, including due to overloaded power grids and insufficient infrastructure. The Andalusian Human Rights Association denounced the government’s failure to resolve power cuts, which reportedly occurred only in poor neighborhoods. In August 2022, the Ombudsman of Andalusia warned that power outages during a heatwave are a “serious public health problem and a violation of the right of people to access and enjoy an essential service such as the supply of energy” (non-official translation).

Recommendations

To the Andalusian Government:

- Evaluate and revise the Andalusian Heatwave Action Plan with the meaningful participation of the most adversely affected, including people with disabilities and groups representing them, particularly those with lived experience of dealing with extreme heat, to ensure future planning protects the rights of people with disabilities.

- Put in place a mechanism to monitor the implementation of the Andalusian Heatwave Action Plan, in particular with an aim to assess people with disabilities’ access to heatwave-related actions.

- Ensure protection of people with disabilities in case of all extreme weather events, in line with the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.

- Ensure inclusive design, planning, and implementation of all policies and plans on extreme weather events and climate change.

- Establish targeted outreach and other support services for people with disabilities, including those facing social isolation or economic marginalization, including during heatwaves.

- Ensure an uninterrupted energy supply during extreme temperatures.

- Provide emergency messaging methods and emergency preparedness and response programs that are inclusive of and accessible to everyone.

- Develop methods and programs to reduce the negative impact of heatwaves in consultation with people with disabilities and groups representing them.

- Increase renovations of residential buildings to make housing more energy efficient, targeting neighborhoods at highest risk of adverse impacts of heatwaves, and ensure people with disabilities have access to these programs.

- Take concrete steps to ensure meaningful participation of people with disabilities in regional forums dedicated to climate change or disability rights, such as the regional advisory group (Consejo Andaluz de Atención a las Personas con Discapacidad).

- Collect and regularly publish data on the impact of heatwaves, including data on heat-related mortality, and disaggregate this data by age, disability, and other relevant categories.

To the Municipal Governments:

- Mandate urban planning that improves heatwave resilience, including by promoting green spaces in residential neighborhoods.

- Ensure that urban sustainability planning abides by standards of universal design, understood as the development of an environment to the greatest extent accessible by everyone, regardless of disability.

- Meaningfully and equally involve people with disabilities in climate change negotiations and discussions, including in developing heat-related information in multiple formats that are accessible to all.

To the Carlos III Health Institute:

- Collect and regularly publish data on the impact of heatwaves, including data on heat-related mortality, and disaggregate this data by age, disability, and other relevant categories.

- Conduct a study on the impact of extreme heat and other extreme weather events on people with disabilities in consultation and with the meaningful involvement of people with disabilities.

- When submitting reports and recommendations to the Spanish government on extreme weather events, including heatwaves, include the perspectives, rights, and needs of people with disabilities with an aim to ensure their protection.