Summary

The garment and footwear industry stretches around the world.[1] Clothes and shoes sold in stores in the US, Canada, Europe, and other parts of the world typically travel across the globe. They are cut and stitched in factories in Asia, Eastern Europe, Latin America, or other regions. Factory workers in Bangladesh or Romania could have made clothes only weeks ago that consumers elsewhere are eagerly picking up.

When global supply chains are opaque, consumers often lack meaningful information about where their apparel was made. A T-shirt label might say “Made in China,” but in which of the country’s thousands of factories was this garment made? And under what conditions for workers?

There is a growing trend of global apparel companies adopting supply chain transparency[2]—starting with publishing the names, addresses, and other important information about factories manufacturing their branded products. Such transparency is a powerful tool for promoting corporate accountability for garment workers’ rights in global supply chains.

Transparency can ensure identification of global apparel companies whose branded products are made in factories where bosses abuse workers’ rights. Garment workers, unions, and nongovernmental organizations can call on these apparel companies to take steps to ensure that abuses stop and workers get remedies.

Publishing supply chain information builds the trust of workers, consumers, labor advocates, and investors, and sends a strong message that the apparel company does not fear being held accountable when labor rights abuses are found in its supply chain. It makes a company’s assertion that it is concerned about labor practices in its supplier factories more credible.[3]

The need for information about factories involved in production for global brands has become painfully clear in recent years through deadly incidents that have plagued the garment industry.

The Rana Plaza building collapse in Bangladesh on April 24, 2013 killed over 1,100 garment workers and injured more than 2,000. In the year before the collapse, two factory fires—one in Pakistan’s Ali Enterprises factory and another in Bangladesh’s Tazreen Fashions factory—killed more than 350 workers and left many others with serious disabilities. These were the deadliest garment factory fires in nearly a century.

Until these tragedies occurred, virtually no public information was available concerning apparel companies that were sourcing from the factories involved. The only way to identify these apparel companies and advocate for accountability was to interview survivors and rummage through the rubble afterward to find brand labels.

A system of corporate accountability that requires people to scramble on the ground for brand labels is the antithesis of “transparency.”

Over the past decade, a growing number of global apparel companies have published information on their websites about factories that manufacture their branded products. For more than a decade, adidas, Levi Strauss, Nike, Patagonia, and Puma have been publishing information on their supplier factories. Over time, more apparel companies and retailers with own-brand products joined them,[4] posting some information about supplier factories on their websites.

As more companies adopt supply chain transparency, it is becoming a cornerstone of responsible business conduct in the garment sector. Increasingly, brands and retail chains are beginning to understand that being an ethical business requires them to publish where their own-brand clothes or footwear are being made.

|

Tracing Supply Chain Transparency in the Garment Industry Until less than two decades ago, no major apparel company published its global supplier factories network. The companies viewed the identity of supplier factories as sensitive business information, and thought disclosure would put them at a competitive disadvantage. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, major apparel brands Nike and adidas began disclosing the names and addresses of factories that produced US collegiate apparel.[5] This was a result of a campaign led by a campus network, United Students Against Sweatshops (USAS), in dozens of universities. Universities included supply chain disclosure as part of their licensing agreements with top athletic apparel companies that produced their college logo apparel. Subsequently, in 2005, Nike and adidas went further by publishing information about all of their supplier factories for all products—not just collegiate licensed apparel. Over the past decade, a growing number of other global apparel companies, including North American companies with no connection to the US collegiate apparel sector like Levi Strauss and Patagonia, as well as some European apparel companies, began publishing supplier factory information. |

***

|

Apparel Companies Publishing Supplier Factory Information in 2016 As of December 2016, the following apparel companies were among those that published some supply chain information about their branded products: adidas, C&A, Columbia Sportswear, Cotton On Group, Disney, Esprit, Forever New, Fruit of the Loom, Gap Inc., G-Star RAW, Hanesbrands, H&M Group, Hudson’s Bay Company, Jeanswest, Levi Strauss, Lindex, Marks and Spencer, Mountain Equipment Co-op, New Balance, Nike, Pacific Brands, PAS Group, Patagonia, Puma, Specialty Fashion Group, Target USA, VF Corporation, Wesfarmers Group (Kmart and Target Australia, and Coles), and Woolworths. This is not a comprehensive list.[6] |

This report takes stock of supply chain transparency in the garment industry four years after the industry disasters in Bangladesh and Pakistan that shook the global garment industry. To build momentum toward supply chain transparency and develop industry minimum standards, a coalition of labor and human rights groups asked 72 companies to agree to implement a simple Transparency Pledge. It also asked that companies declining to commit to the Pledge provide reasons for choosing not to do so.[7] Where companies engaged with the coalition, the coalition also sought additional information about their existing transparency practices. This report explains the logic and the urgency behind the Pledge and describes the responses we received from the companies contacted.[8] Further information about the apparel companies contacted, the reasons for choosing them, and the coalition’s engagement process is outlined in Appendix I.

Supply chain transparency practices vary immensely among companies. Among those apparel companies that embrace transparency, the details they publish are inconsistent.[9] Many other companies refuse to publish supplier factory information at all, or divulge only scant information. Some companies attempt to justify non-disclosure on commercial grounds. But their explanations are belied by the experiences of other similarly situated companies that do publish and have shown that the benefits of disclosure outweigh perceived risks.[10]

Ultimately apparel companies can do far more than implement the Pledge to ensure respect for human rights in their supply chains. Nonetheless, this is one important step in a holistic effort to improve corporate accountability in the garment industry.

|

Civil Society Coalition on Garment Industry Transparency In 2016, nine labor and human rights organizations formed a coalition to advocate for transparency in apparel supply chains. Coalition members are:

|

I. The Case for Supply Chain Transparency

Supply chain transparency—starting with publishing names, addresses, and other important information about factories producing for global apparel companies—is a powerful tool to assert workers’ human rights, advance ethical business practices, and build stakeholder trust. Consumers should know where the products they purchase are made. Workers should also know which apparel company’s branded products they are making.

Companies have a responsibility to take steps to prevent human rights risks throughout their supply chains, and to identify and address any abuses that arise despite those preventative efforts. In order to live up to that responsibility, they should adopt industry good practices.

By publishing factory names, street addresses, and other important information, global apparel companies allow workers and labor and human rights advocates to alert apparel companies to labor rights or other abuses in their supplier factories.

An apparel company that does not publish its supplier factory information contributes to possible delays in workers or other stakeholders being able to access the company’s complaint mechanisms or other remedies. Workers and labor rights advocates often expend substantial time and effort trying to collect brand labels or using other methods to determine which companies are sourcing from factories where human rights abuses are occurring. Meanwhile, they lose valuable time and put workers at risk of retaliation and continued exposure to dangerous or abusive working conditions. Such delays reduce the overall effectiveness of grievance redress mechanisms that apparel companies and other parties put in place.

Disclosing names, addresses, and other relevant information about supplier factories helps make it possible to determine whether a brand has sufficient leverage or influence in a particular factory or country to achieve remediation of worker rights abuses.

Supply chain transparency can also help check unauthorized subcontracting, in which factories that contract with apparel companies meet production demands by farming out some of the work, often to smaller, less regulated factories where labor rights abuses are common. This is a persistent challenge in the garment industry. If apparel companies published the names and addresses of all authorized supplier factories and their subcontract facilities, workers and other interested parties would know which factories are authorized to produce for the company and which are not.

Publishing supplier factory information can also help apparel companies avoid reputational harm. For example, workers may not know that a given apparel company has terminated business with a factory well before labor rights problems arose, and could seek a remedy from the wrong company. Many factories publish information on their websites about their business relationships with major brands that may be outdated and misleading. By publishing supplier factory information themselves, and updating it regularly, apparel companies would reduce the risk that they could be wrongly associated with abusive conditions in factories with which they long before cut business ties.

Moreover, it is difficult for companies to continually identify persistent labor rights problems in specific supplier factories, to detect unauthorized subcontracting, and to regularly verify progress toward corrective action if they limit their sources of information to purely business-led human rights due diligence procedures. These include inspections and labor compliance audits by apparel companies’ own social compliance staff and third-party monitors engaged by them.

Brand inspectors and third-party monitors—even those that are diligent and professional—are at best able to visit factories periodically and for short periods. The quality and accuracy of third-party monitoring reports depend largely on the methodology used in the assessments, the independence of the assessors from the factory and the apparel company, and the weight given to testimonies from workers and other interested parties. These tools are not sufficient in and of themselves to detect all instances of abuse, unauthorized subcontracting, and other problems. Factory disclosure makes it possible for apparel companies to receive credible information from workers and worker rights advocates between periodic factory audits.

An easily achievable standard of disclosure is for apparel companies to publish on their company websites factory names and addresses (including country, city, and street address). Many leading apparel companies have already done this. In Section III, we describe additional steps apparel companies can and should take to make their supply chains more transparent.

Publishing supply chain information is consistent with a company’s responsibilities under the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UN Guiding Principles), a set of guidelines that lay out steps companies should take to prevent, address, and remedy human rights abuses linked to business operations. The principles state that companies have a responsibility to “identify, prevent, mitigate and account for” adverse human rights impacts of their business operations, and to regularly report on progress made.[11]

The UN Guiding Principles also say that businesses should externally communicate how they address their human rights impacts in “a form and frequency that … are accessible to its intended audiences.”[12] The commentary on the Guiding Principles states that the “responsibility to respect human rights requires that business enterprises have in place policies and processes through which they can both know and show [emphasis added] that they respect human rights in practice.” Further, “[s]howing involves communication, providing a measure of transparency and accountability to individuals or groups who may be impacted and to other relevant stakeholders, including investors.”[13]

In some jurisdictions, companies that publish supplier factory information can also help facilitate compliance with legal obligations under laws like the California Transparency in Supply Chains Act of 2010; “sweat-free” procurement laws adopted in dozens of US cities and a few states; the UK Modern Slavery Act 2015; and the French law on the corporate duty of vigilance, 2017.[14]

The transparency of global supply chains is also increasingly recognized by investors as a metric for evaluating the robustness of business human rights practices. The Corporate Human Rights Benchmark (CHRB), a collaborative effort by business and human rights organizations and investors, developed a public scorecard for the human rights practices of apparel, agricultural, and extractive companies. The benchmark has been endorsed by 85 investors representing US$5.3 trillion in assets.[15] CHRB’s indicators include whether the company publishes supply chain information.

Specifically, the CHRB scorecard assesses whether “[t]he Company maps its suppliers and discloses its mapping publicly [emphasis added].” Apparel companies are given two specific scores depending on whether “[t]he company indicates that it maps its suppliers beyond tier one, including direct and indirect suppliers, and describes how it goes about this” and whether “[t]he Company also discloses the mapping for the most significant parts of its supply chain and explains how it has defined what are the most significant parts of its supply chain.”[16] In order to assess the latter, companies were required to publish at least the names of its supplier factories for the 2016 pilot benchmark.[17]

|

Kevin Thomas, director of shareholder engagement of SHARE Canada, a nonprofit organization that represents institutional investors in Canadian and other international companies in apparel and other sectors, said that in 2016 at least 20 shareholder resolutions related to supply chains and human rights practices were filed in the US. He said: [I]nvestors are looking for evidence that demonstrates that the company is effectively identifying human rights risks in its own operations and in the supply chain, and has an effective system to address those risks when they are identified. It’s important that the company not only report on its policies and systems, but also the outcomes of its work – what is it finding, and how is it fixing it. Factory disclosure is a part of that process. [T]he company’s willingness to disclose demonstrates to shareholders that it is confident in its due diligence process. [I]t also assists the company in catching unauthorized subcontracting, as well as developing useful relationships with stakeholders that can assist the company in identifying problem areas and solutions.[18] |

II. The Transparency Pledge

The objective of the Transparency Pledge is to help the garment industry reach a common minimum standard for supply chain disclosures by getting companies to publish standardized, meaningful information on all factories in the manufacturing phase of their supply chains. The civil society coalition that developed the Pledge based it on published factory lists of leading apparel companies and developed a set of minimum supply chain disclosure standards. These build on good practices in the industry.

|

The Apparel and Footwear Supply Chain Transparency Pledge (“The Transparency Pledge”) This Transparency Pledge helps demonstrate apparel and footwear companies’ commitment towards greater transparency in their manufacturing supply chain. Transparency of a company’s manufacturing supply chain better enables a company to collaborate with civil society in identifying, assessing, and avoiding actual or potential adverse human rights impacts. This is a critical step that strengthens a company’s human rights due diligence. Each company participating in this Transparency Pledge commits to taking at least the following steps within three months† of committing to it: Publish Manufacturing Sites The company will publish on its website on a regular basis (such as twice a year) a list naming all sites that manufacture its products. The list should provide the following information in English:

Companies will publish the above information in a spreadsheet or other searchable format. † The three-month time frame was extended to December 2017 based on the coalition’s engagement with apparel companies. See Appendix I for details. * Processing factories include printing, embroidery, laundry, and so on. ** Please indicate the broad category—apparel, footwear, home textile, accessories. *** Please indicate whether the site falls under the following categories by number of workers: Less than 1,000 workers; 1,001 to 5,000 workers; 5,001 to 10,000 workers; More than 10,000 workers. |

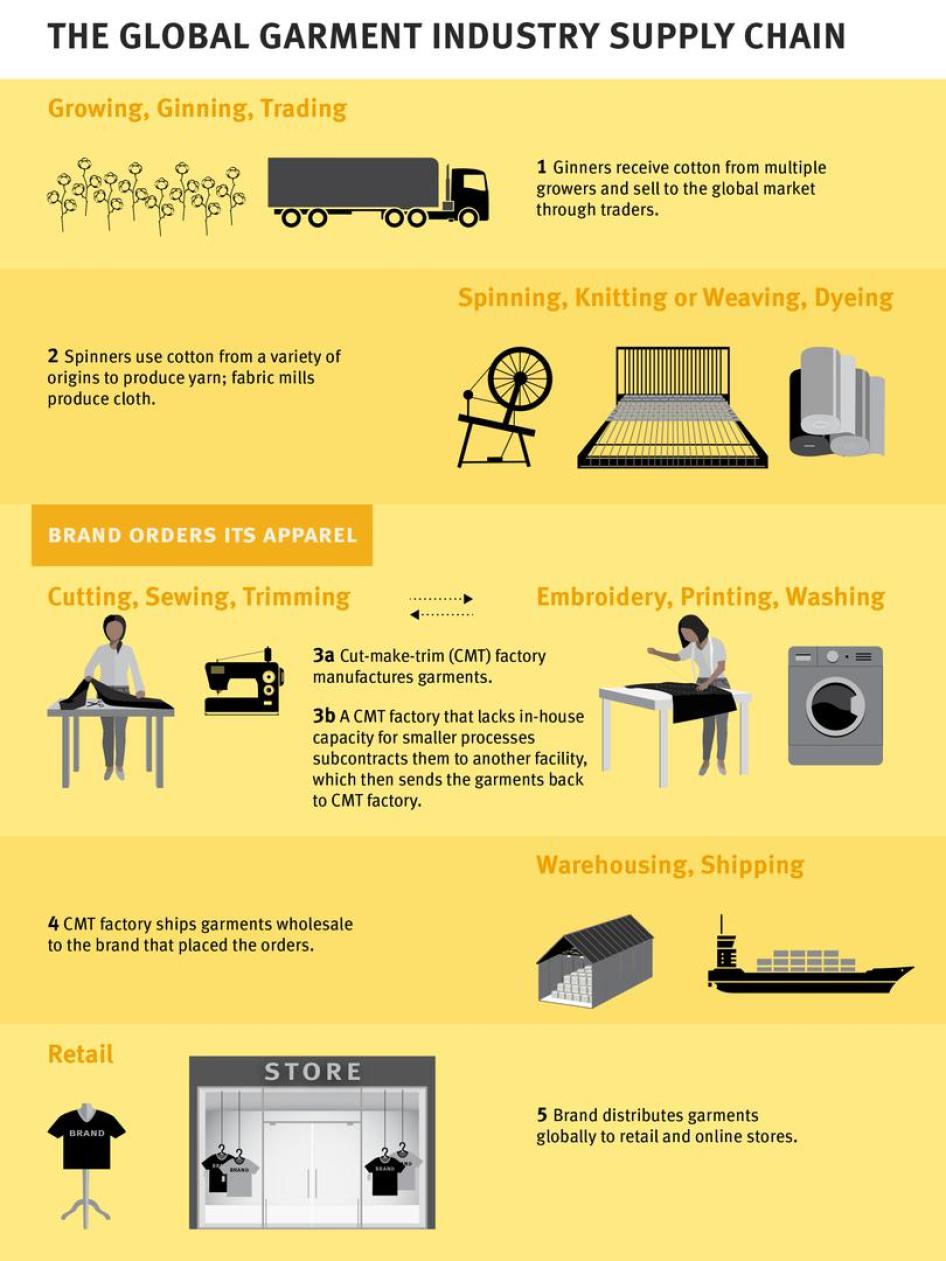

The Pledge focuses on the “manufacturing phase” of an apparel company’s supply chain, which comprises all factories authorized by the company to produce (that is, cut-make-trim, or CMT) along with others subcontracted by these CMT factories to perform “finishing” processes.[19]

The Pledge aims for consistency in disclosures, which is sorely needed, as shown by an analysis carried out by coalition members of supply chain information published by September 2016 by 23 global apparel companies. In the absence of standards, companies adopt different approaches to transparency, sometimes excluding important information that makes it effective. This analysis informed the content of the Transparency Pledge, as explained in Appendix II.

|

Why Minimum Standards for Disclosure Based on an analysis of apparel companies’ disclosure practices, it became clear that without minimum standards, companies’ efforts toward supply chain disclosures suffered from a range of deficiencies:

Key Pointers for Publishing Supplier Factory Information When publishing supplier factory information, global apparel companies should pay close attention to the manner in which they provide it. The following guiding points are important to make disclosure effective: Easy Access

Clarity

Regular Updates

What the Transparency Pledge Does Not Do The Pledge does not attempt to define the full extent of transparency in the garment industry. It deals with a narrow yet critical part of transparency in apparel supply chains. The full range of transparency practices in the garment industry should be broader and more holistic. Several aspects—ranging from grievance redress procedures and brand efforts to mitigate or remediate human rights problems, including the effectiveness of brands’ compliance programs with respect to worker wages, hours of work, and their freedom of association—stand to benefit from greater transparency.

Some brands have already taken steps that prove more is possible. They have published more details beyond just a factory name and address, indicating the precise number of workers in the factory, the gender breakdown of the workforce, and other details for every factory disclosed.[20] A very small number of apparel companies have published the textile factories where fabric used in their garments is made and more information beyond the “manufacturing phase” of the supply chain.[21] |

III. Apparel Company Responses

The civil society coalition that developed the Transparency Pledge contacted 72 apparel and footwear companies asking them to sign on to and implement the Pledge. This section captures responses received as of April 7, 2017.[22]

There were a wide range of responses, which the coalition has grouped into three categories:

- First, some companies already embrace supply chain transparency and either agreed to add more factory details to meet the Pledge standards or to align their practices more closely with those standards.

- Second, some companies already publish supplier factory information but declined to add more details to align their disclosure practices with the Pledge standards, or failed to respond to the coalition letter. In the same category are other companies that reported that they intend to begin disclosing more supplier factory information but whose commitments fell far short of the Pledge standards.

- Third, some companies either did not commit to publishing any supplier factory information or did not respond at all.

These categories are based on commitments made by apparel companies—many of which have promised to begin publishing information for the first time—that they have indicated will be implemented in 2017. An update to this report will be issued in 2018 providing more details about apparel company disclosures and additional responses. Where appropriate the list of companies in each category will be revised, based on the disclosures and commitments that these companies make in the interim period.

Full Pledge or Close to Full Alignment with Pledge

Seventeen apparel companies agreed to publish all supplier factory information requested, meeting all the Pledge standards.[23] Another five companies fell just short of the Pledge standards.

|

Full Alignment with the Pledge Apparel companies that previously published supply chain information and committed to publishing additional supplier factory information in full alignment with the Pledge standards are adidas, C&A, Cotton On, Esprit, G-Star RAW, Hanesbrands, H&M, Levis, Lindex, Nike, and Patagonia. Apparel companies that had previously not published any supplier factory information and have committed to publishing this in full alignment with the Pledge are ASICS, ASOS, Clarks, New Look, Next, and the Pentland Brands. The commitments of these global apparel companies help break new ground by promoting an industry-wide minimum standard for supply chain transparency. Just Missing the Pledge Standard Since its first disclosure in September 2016, Gap updated its information, which now incorporates almost all aspects of the Pledge.[24] Marks and Spencer[25] and Tesco[26] outlined their plans to add more information to their current factory disclosure, which would bring them closer to alignment with the Pledge standard. John Lewis committed to publishing supplier factory information in 2017 in accordance with almost the full Pledge.[27] None of these companies committed to publishing information about parent companies of factories as requested. Mountain Equipment Co-op added information in accordance with Pledge standards for cut-make-trim factories with a commitment to adding authorized subcontractors in the future.[28] |

Some Transparency, More Needed

Some apparel companies (identified in textboxes below) already publish the names and addresses of their supplier factories, but do not disclose other information in line with the Pledge standards, and did not commit to doing more. Others have committed to taking steps to publish supplier factory information but with scant detail or without specifying what precisely they will disclose.

An apparel company should, at the very least, publish the minimum information needed to demonstrate that it “knows and shows” a key part of its supply chain: the names and addresses of all its cut-make-trim factories and authorized subcontractors that undertake processes needed to finish the product.

|

In the Right Direction Columbia Sportswear and Disney have been publishing the names and addresses of their cut-make-trim suppliers and authorized subcontractors.[29] But they did not explicitly commit to doing more.[30] New Balance, which was already publishing factory names and addresses, committed to adding product categories.[31] PUMA added street addresses, worker numbers, and product categories for all factories it currently publishes.[32] Coles publishes the names and addresses of its non-food suppliers (not only apparel) from India and China, which the company says includes all supplier factories, but it did not commit to doing more.[33] Under Armour committed to publishing information for all cut-make-trim factories in accordance with Pledge standards in 2017.[34] ALDI North and ALDI South published the names and street addresses of their tier-1 suppliers.[35] LIDL committed to beginning disclosure in 2017, which would list the names and street addresses for all tier-1 factories producing own-brand products.[36] Tchibo committed to publishing the names, addresses, and product types of cut-make-trim factories in 2017.[37] VF Corporation committed to adding factory street addresses to its existing publication of owned and operated and tier-1 supplier factory names,[38] but this excludes “licensee and sub-contractor factories.”[39] Debenhams committed to publishing in 2017 the names and addresses of its tier-1 factories along with worker numbers by gender breakdown.[40] Benetton published its tier-1 factories in 2017 listing the names, addresses, and product category.[41] Arcadia Group has committed to publish the names and addresses of all cut-make-trim factories in 2017.[42] Many Factories Still Missing from Disclosure Lists The apparel companies named below publish the names and addresses of some factories. But these companies still leave out many cut-make-trim factories and their authorized subcontractor facilities from their factory lists. Woolworths has suppliers across many countries and responded that it already publishes the names and addresses of all factories in Bangladesh and “overall more than 40 percent” of its apparel supply chain.[43] Their subcontractor facilities are currently only partially disclosed (i.e. for Bangladesh) and the company says it is improving visibility of subcontractors in other countries.[44] Based on the information given on their respective websites, Kmart Australia appears to publish all apparel factories in “high risk” countries that directly produce Kmart products[45] and Target Australia appears to publish the names and addresses of cut-make-trim factories.[46] But because these companies did not respond to the coalition’s letter, the coalition has no information about the percentage of supplier factories they disclose and whether authorized subcontractors are included.[47] The Hudson’s Bay Company did not commit to adding more disclosures to its existing factory list, which carries the names and addresses of some, but not all, of its cut-make-trim supplier factories.[48] Fast Retailing began disclosing the names and addresses of its “core factories list” producing for UNIQLO, the largest of its brands, for the first time in 2017.[49] |

Other companies named in the text box below already disclose or have indicated they support some degree of supply chain transparency. But they either disclose or have committed to disclosing only factory names without street addresses. Some have only stated that they plan to begin disclosing in 2017, without indicating what precisely they will disclose.

|

Beginning to Disclose Target USA was already disclosing factory names by country and city for manufacturing, textile, and wet-processing factories but did not respond in substance to the coalition’s letter asking for more information to be published about supplier factories.[50] Mizuno committed to publishing its “core factory list” in January 2017 with “names, location, and product category,” but published the information without including factory street addresses.[51] This list also appears to include only a minority of all Mizuno’s apparel supplier factories.[52] Abercrombie & Fitch and PVH Corporation communicated their decisions to publish all tier-1 factory names by country only.[53] Loblaw similarly committed to publish names of all factories where they “source apparel and footwear directly” and to include the country of manufacture but not the factory address.[54] Beginning Disclosure, But Details Unknown BESTSELLER and Decathlon committed to beginning publishing supplier factory information in 2017 but did not specify the details of their disclosure.[55] |

No Commitment to Publish

Some companies gave little or no response to letters requesting information about their disclosure practices or plans, or the Transparency Pledge.

Of the apparel companies and retailers with own-apparel brands who had previously not published any information for cut-make-trim factories, 10 did not send any response to the coalition’s letter.[56] Another 15 did not commit to publish supplier factory information.[57]

|

No Commitment to Make their Factory List Public Apparel companies that responded but did not indicate any impending commitment to publishing their supplier factories are American Eagle Outfitters, DICK’S Sporting Goods, Foot Locker,[58] The Children’s Place, Walmart, Canadian Tire, Desigual, MANGO, KiK, Hugo Boss, Carrefour, Morrison’s, Primark, and Sainsbury’s. Inditex declined to publish supplier factory information but makes this data available to IndustriALL and its affiliates as part of the reporting under its Global Framework Agreement.[59] Failed to Respond to Coalition’s Call for Transparency Armani, Carter’s, Forever 21, Urban Outfitters, Ralph Lauren Corporation, Matalan, River Island, Sports Direct, Shop Direct, and Rip Curl did not send any response to the coalition. |

Debunking the So-Called Barriers to Transparency

Competitive Disadvantage

A few brands—KiK, Inditex, DICK’s Sporting Goods, and The Children’s Place—that declined to publish their supplier factory information cited competitive advantage.[60] However, many other large apparel companies and retailers with own-brand apparel products have published supplier factory information for years.[61] Five companies have published this information for more than a decade.[62] Garment industry giants are increasingly choosing to publish their supplier information, proving that transparency can easily coexist with being competitive.

In some cases, supplier factories already openly advertise on their websites the names of brands they produce for, even where a brand does not.[63]

Many apparel companies are also part of initiatives like the Fair Factories Clearinghouse and Sedex, where they voluntarily disclose and share non-competitive information with other brands, including supplier names, audit reports, and so on, even where they do not do so publicly.[64]

Moreover, apparel companies that import products into US markets are subject to the US law, which requires that customs authorities collect information on each shipping container that enters a US port, including the shipper (typically in the case of garments the overseas supplier) and the consignee (typically the apparel company or its agent).[65] Online subscription databases purchase this trade data and market it in searchable formats, allowing users, including competitors, to gather information about suppliers to apparel companies that import goods into the US.[66] But the costs of accessing such subscription-based databases are prohibitive for workers and many civil society organizations. While apparel companies can easily purchase subscriptions, workers and many labor advocates around the world cannot afford them. Despite the availability of these records, some companies are known to use various means of shielding their own names and their suppliers’ names from appearing in this data.

Anti-Competition Law

KiK declined to publish information about their supplier factories, raising anti-competition concerns among others.[67] However, other brands selling products in Germany or other EU countries are governed by the same laws as KiK. They have been disclosing supplier information for many years; and more brands operating there have committed to begin public disclosure. These include companies that already disclose supplier factory information, such as adidas, C&A, Columbia Sportswear, Disney, Esprit, H&M, Levi’s, Nike, Patagonia, and Puma; and others that have committed to beginning disclosure in 2017, such as ALDI North and ALDI South, BESTSELLER, Fast Retailing, LIDL, and Tchibo.

Moving Beyond Private Disclosure

In response to the coalition’s recommendation that brands publicly disclose their supplier information, a few brands declined, citing their participation in other initiatives, like the Bangladesh Accord on Fire and Building Safety or global framework agreements (GFA) with IndustriALL and UNI Global Union.

When implemented effectively, such initiatives serve important human rights due diligence purposes. For example, the Bangladesh Accord requires brands to confidentially disclose their supplier factory information to the initiative’s Steering Committee and staff, which makes public the names of all factories covered by the Accord and their performance on building safety issues, but without disclosing the specific brands that are supplied by each factory. An apparel company’s global framework agreement with IndustriALL typically requires the company to disclose its factory lists to the global union. This creates a basis for the union to engage with the company on the behavior of particular supplier factories.

However, none of these agreements prevent brands from publishing their supplier factory information. A number of brands (named in the text box below) participate in the Bangladesh Accord and publish their supplier factory information. Apparel companies H&M, Tchibo, and Mizuno have shown that private, confidential reporting within the framework of legally binding agreements can and should complement publishing supplier factory information.

|

Brands that Do Both: Publish Supplier Information and Participate in Other Initiatives Bangladesh Accord members that have been publishing supplier factory information include adidas, C&A, Cotton On, Esprit, G-Star RAW, H&M, Kmart Australia, Lindex, Marks and Spencer, Puma, Target Australia, and Woolworths. Accord members that will begin some disclosure in 2017 are Abercrombie & Fitch, ALDI North and ALDI South, BESTSELLER, Debenhams, Fast Retailing, John Lewis, Next, New Look, Loblaw, LIDL, PVH, Tesco, and Tchibo. A number of brands that are a part of the German Partnership for Sustainable Textiles (the Textil Bündnis) publish their supplier information: adidas, C&A, Esprit, H&M, and Puma; others like ALDI North and ALDI South and LIDL began publishing supplier factory information in 2017; Tchibo will also publish its supplier factory information in 2017. A number of brands that are a part of the German Partnership for Sustainable Textiles (the Textil Bündnis) publish their supplier information: adidas, C&A, Esprit, H&M, and Puma; others like ALDI North and ALDI South and LIDL began publishing supplier factory information in 2017; Tchibo will also publish its supplier factory information in 2017. |

MANGO, in response to outreach about the Transparency Pledge, offered an alternative: disclosing only to members of the coalition that spearheaded the Pledge, or to parties that register with the company.[68] These proposals fall short of the level of supply chain transparency needed in the industry. Private disclosure of this type is not sustainable, and does little to improve human rights due diligence in global apparel supply chains.

IV. The Way Forward

Supply chain transparency is an important first step toward more meaningful corporate accountability. As Esprit, one of the global apparel companies that committed to improve its disclosure practices to align with the Pledge, said: “[R]eleasing this information is not comfortable for many companies, but the time has come to do it.”[69]

A number of companies have responded positively to the coalition’s letter committing to add more information in accordance with the Pledge standards. More companies should step out of their comfort zone and join the transparency trend. They should commit to the Transparency Pledge standards.

Multi-stakeholder initiatives should also endorse the Transparency Pledge as a minimum standard for apparel supply chain transparency for their member companies, and publicly scorecard members on transparency practices.

Investors should also endorse the Transparency Pledge as part of broader efforts to promote effective human rights due diligence tools that are industry good practice and in accordance with the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights.

The Transparency Pledge is an important first step, but is not the end of the story. Far more can and should be done to promote deeper and wider transparency and human rights in garment industry supply chains.

All global apparel companies, including those acknowledged in this report as committing to the Pledge or close, should periodically review and upgrade their transparency practices.

These efforts should include expanding traceability and transparency beyond the cut-make-trim manufacturing phase to other aspects of the supply chain, including manufacture of yarn, fabric, and other inputs, and the production of raw materials like cotton.

While supply chain transparency is widely recognized as an important pillar on which corporate accountability is built, transparency alone does not result in improved working conditions or accountability. Brands should adopt transparent practices and complement them with other steps to strengthen human rights due diligence in their supply chains.

Countries where global apparel companies do business should pass legislation that promotes mandatory human rights due diligence in the global supply chains of companies, including mandatory publication of supplier information. These should build on the California Transparency in Supply Chains Act, “sweat-free” procurement laws adopted by dozens of local governments in the US, the UK Modern Slavery Act and the 2017 French law on corporate duty of vigilance.[70] Such legislation will go a long way in creating a level playing field in the garment industry.

[The coalition invites additional endorsements from labor and human rights organizations, apparel companies, and investors interested in supporting the move for industry-wide minimum standards for transparency in garment supply chains, starting with the Transparency Pledge. Inquiries may be sent to: transparency@hrw.org or any coalition member.]

Acknowledgments

This report was authored and edited by the following people:

Human Rights Watch: Aruna Kashyap, senior counsel and Janet Walsh, acting director, Women’s Rights Division; Arvind Ganesan, director, Business and Human Rights Division; Chris Albin-Lackey, senior legal advisor; Tom Porteous, deputy program director; and Danielle Haas, senior editor, Program Office.

Maquila Solidarity Network: Lynda Yanz, executive director; and Robert Jeffcott, policy analyst.

Clean Clothes Campaign (International Office): Ben Vanpeperstraete, lobby and advocacy coordinator; and Christie Miedema, campaign and outreach coordinator.

International Corporate Accountability Roundtable: Nicole Vander Meulen, legal and policy associate.

Worker Rights Consortium: Scott Nova, executive director; and Ben Hensler, general counsel and deputy director.

International Labor Rights Forum: Judy Gearhart, executive director; and Liana Foxvog, director of organizing and communications.

International Trade Union Confederation: Alison Tate, director of economic and social policy.

IndustriALL Global Union

A number of people contributed to this collective advocacy effort by coordinating outreach with brand representatives. They include:

- Clean Clothes Campaign: Ben Vanpeperstraete, Dominique Muller, Laura Ceresna, Deborah Lucchetti, Ineke Zeldenrust, Frieda de Koninck, and Helle Løvstø Severinsen.

- Human Rights Watch: Aruna Kashyap.

- IndustriALL Global Union.

- International Trade Union Confederation.

- Maquila Solidarity Network: Lynda Yanz and Robert Jeffcott.

- UNI Global Union.

- Worker Rights Consortium: Ben Hensler and Scott Nova.

Human Rights Watch also acknowledges the contribution of Shubhangi Bhadada, a consultant who helped with desk research, and Kate Larsen, a former Human Rights Watch consultant.

Alexandra Kotowski and Annerieke Smaak, senior coordinators of the women’s rights division of Human Rights Watch, assisted with brand outreach along with Helen Griffiths, the coordinator of the Children’s Rights Division of Human Rights Watch. Kate Segal, part-time coordinator for the women’s rights division, assisted in the production of this report along with Grace Choi, the design and publications director at Human Rights Watch.

***

[1] The terms garment industry, apparel industry, and garment and footwear industry are used interchangeably in this report. All references to the garment or apparel industry also include the footwear industry.