Update 9/8/2021: In a letter dated August 17, 2021, General Joseph Aoun, the Commander of the Lebanese Armed Forces, responded to Human Rights Watch stating that the Army Command is unable to answer questions on the events that led to the Beirut Blast, as they relate to an ongoing investigation.

Summary

Following decades of government mismanagement and corruption at Beirut’s port, on August 4, 2020, one of the largest non-nuclear explosions in history pulverized the port and damaged over half the city. The explosion resulted from the detonation of tonnes of ammonium nitrate, a combustible chemical compound commonly used in agriculture as a high nitrate fertilizer, but which can also be used to manufacture explosives. The cargo of ammonium nitrate had entered Beirut’s port on a Moldovan-flagged ship, the Rhosus, in November 2013, and had been offloaded into hangar 12 in Beirut’s port on October 23 and 24, 2014.

The Beirut port explosion killed 218 people, including nationals of Lebanon, Syria, Egypt, Ethiopia, Bangladesh, Philippines, Pakistan, Palestine, the Netherlands, Canada, Germany, France, Australia, and the United States. It wounded 7,000 people, of whom at least 150 acquired a physical disability; caused untold psychological harm; and damaged 77,000 apartments, displacing over 300,000 people. At least three children between the ages of 2 and 15 lost their lives. Thirty-one children required hospitalization, 1,000 children were injured, and 80,000 children were left without a home. The explosion affected 163 public and private schools and rendered half of Beirut’s healthcare centers nonfunctional, and it impacted 56 percent of the private businesses in Beirut. There was extensive damage to infrastructure, including transport, energy, water supply and sanitation, and municipal services totaling US$390-475 million in losses. According to the World Bank, the explosion caused an estimated $3.8-4.6 billion in material damage.

The explosion also resulted in ammonia gas and nitrogen oxides being released into the air, potentially with toxins from other materials that may have also ignited as a result of the explosion. Ammonia gas and nitrogen oxides are harmful to the environment as well as to the respiratory system. The destruction is estimated to have created up to 800,000 tonnes of construction and demolition waste that likely contains hazardous chemicals that can damage health through direct exposure, or soil and water contamination. The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) has estimated that the cost of cleaning up the environmental degradation from the explosion will be over $100 million.

The evidence, as currently known, raises questions regarding whether the ammonium nitrate was intended for Mozambique as the Rhosus’s shipping documents stated or whether Beirut was the intended destination for the material. The evidence currently available also indicates that multiple Lebanese authorities were, at a minimum, criminally negligent under Lebanese law in in their handling of the Rhosus’s cargo. The actions and omissions of Lebanese authorities created an unreasonable risk to life. Under international human rights law, a state’s failure to act to prevent foreseeable risks to life is a violation of the right to life.

In addition, evidence strongly suggests that some government officials foresaw the death that the ammonium nitrate’s presence in the port could result in and tacitly accepted the risk of the deaths occurring. Under domestic law, this could amount to the crime of homicide with probable intent, and/or unintentional homicide. It also amounts to a violation of the right to life under international human rights law.

A chronology of events related to the Rhosus and its cargo, starting in September 2013, can be found in Annex 1 of this report.

In this report, Human Rights Watch details the evidence of omissions and actions by officials that, in a context of longstanding corruption and mismanagement at the port, allowed for such a potentially explosive compound to be haphazardly stored there for nearly six years. The very design of the port’s management structure was developed to share power between political elites. It maximized opacity, and allowed corruption and mismanagement to flourish.

Drawing on official correspondence regarding the Rhosus and its cargo, some of which has not been published before, the report outlines what is currently known about how the ammonium nitrate arrived in Beirut and was stored in hangar 12 in the port. Through a review of dozens of official documents sent from and to officials working under the Ministry of Finance, including customs officials; the Ministry of Public Works and Transport, including port officials; members of the judiciary; the Case Authority (a body at the Ministry of Justice which acts as the legal representative of the Lebanese state in judicial proceedings); members of the Higher Defense Council, including the president and prime minister; the Ministry of Interior; General Security; and State Security, among others, the report provides insights into which government officials knew about the ammonium nitrate and what actions they took or failed to take to safeguard the population from its dangerous long-term presence there. Interviews with government, security, and judicial officials, defense lawyers for officials who have been charged, investigative journalists, and others, provided further insights into the actions government officials took or failed to take despite being informed of the risks.

Evidence indicates that many of Lebanon’s senior leaders, including President Michel Aoun, then-Prime Minister Hassan Diab, the Director General of State Security, Major General Tony Saliba, former Lebanese Army Commander, General Jean Kahwaji, former Minister of Finance, Ali Hassan Khalil, former Minister of Public Works and Transport, Ghazi Zeaitar, and former Minister of Public Works and Transport, Youssef Fenianos, among others, were informed of risks posed by the ammonium nitrate and failed to take the necessary actions to protect the public.

Official correspondence reflects that once the ship arrived in Beirut, Ministry of Finance and Ministry of Public Works and Transport officials failed to correctly communicate or adequately investigate the potentially explosive and combustible nature of the ship’s cargo, and the danger it posed. Ministry of Public Works and Transport officials inaccurately described the cargo’s risks in their requests to the judiciary to offload the merchandise and knowingly stored the ammonium nitrate in Beirut’s port alongside flammable or explosive materials for nearly six years in a poorly secured and ventilated hangar in the middle of a densely populated commercial and residential area. Their practices contravened international ammonium nitrate safe storage and handling guidance. Neither they, nor any security agency operating in the port, took adequate steps to secure the material or establish an adequate emergency response plan or precautionary measures, should a fire break out in the port. They also reportedly failed to adequately supervise the repair work undertaken on hangar 12 that may have triggered the explosion on August 4, 2020.

Official correspondence also indicates that port, customs, and army officials ignored steps they could have taken to secure or destroy the material.

Customs officials repeatedly took steps to sell or re-export the ammonium nitrate that were procedurally incorrect. But instead of correcting their procedural error, they persisted with these same incorrect interventions despite repeatedly being told of the procedural problems by the judiciary. Legal experts even state that customs officials could have acted unilaterally to remove the ammonium nitrate and that they could have sold it at public auction or disposed of it without a judicial order, which they never took steps to do.

The Lebanese Army Command brushed off knowledge of the ammonium nitrate in hangar 12, saying they had no need for the material, even after learning its nitrogen grade classified it under local law as material used to manufacture explosives and required army approval to be imported and inspection. Despite being responsible for all security issues related to munitions at the port, and being informed of the ammonium nitrate in hangar 12, Military Intelligence took no apparent steps to secure the material or establish an appropriate emergency response plan or precautionary measures.

All of this was done despite repeated warnings about the dangerous nature of ammonium nitrate and the devastating consequences that could follow from its presence in the port.

Even after security officials from the Lebanese General Directorate of State Security, the executive agency of the Higher Defense Council chaired by the president, completed an investigation into the ammonium nitrate at the port, there was an unconscionable delay in reporting the threat to senior government officials, and the information they provided about the threats posed by the material was incomplete.

Both the then-Minister of Interior and the Director General of General Security have acknowledged that they knew about the ammonium nitrate aboard the Rhosus, but have said that they did not take action after learning about it because it was not within their jurisdiction to do so.

Once they were informed by State Security, other senior officials on Lebanon’s Higher Defense Council, including the president and the prime minister, also failed to act in a timely way to remove the threat.

Relying on public sources and interviews with impacted individuals, the report recounts the devastating events of August 4 that led to violations of the right to life and other human rights abuses, such as violations of the rights to education and to an adequate standard of living, including the rights to food, housing, health, and property.

Finally, the report documents the failings of the Lebanese domestic investigation into the blast.

In the aftermath of the blast, Lebanese officials vowed that the cause of the explosion would be investigated vigorously and expeditiously. In August 2020, 30 UN experts publicly laid out benchmarks, based on international human rights standards, for a credible inquiry into the blast, noting that it should be “protected from undue influence,” “integrate a gender lens,” “grant victims and their relatives effective access to the investigative process,” and “be given a strong and broad mandate to effectively probe any systemic failures of the Lebanese authorities.”

In the year since the blast, however, a range of procedural and systemic flaws in the domestic investigation have rendered it incapable of credibly delivering justice. These flaws include a lack of judicial independence, immunity for high-level political officials, lack of respect for fair trial standards, and due process violations.

Lebanese authorities have ensured that the domestic investigation that they authorized would remain carefully circumscribed. On August 13, the justice minister named Fadi Sawan the judicial investigator responsible for the investigation. Judge Sawan brought charges against 37 people, but with the exception of the heads of the customs administration and port authority, those detained were mostly mid- to low-level customs, port, and security officials.

While only relatively lower-level officials were detained, senior officials knew of the ammonium nitrate being stored in the port, had a responsibility to act to secure and remove it, and failed to do so. However, investigations of their responsibility have been stymied due to various types of immunities applicable to ministers, parliamentarians, lawyers, and others.

In November 2020, Judge Sawan wrote to parliament asking them to investigate 12 current and former ministers for their role in the August 4 explosion and then refer them to a special body that Lebanese law empowers to try ministers. However, Nabih Berri, the speaker of the parliament, refused to act.

In December 2020, in the absence of parliamentary action, Judge Sawan charged the Caretaker Prime Minister Hassan Diab, and three former government ministers – Ghazi Zeaiter, former Minister of Public Works and Transport; Ali Hassan Khalil, former Minister of Finance; and Youssef Fenianos, former Minister of Public Works and Transport —with criminal negligence related to the blast. The judge was immediately challenged for not having accepted the immunity that politicians typically enjoy in Lebanon. Two of the former ministers, who are also members of Parliament, filed a complaint before the Court of Cassation, the country’s highest court, for Judge Sawan to be removed from the case and in February 2021, the court removed him. His replacement, investigative judge Tarek Bitar, is operating under the same prosecutorial limitations.

On July 2, 2021, Judge Bitar submitted a request to parliament to lift parliamentary immunity for former ministers Khalil, Zeaiter, and Nohad Machnouk, the former Minister of Interior. They are all currently parliamentarians. He also wrote to the Beirut and Tripoli Bar Associations, requesting permission as required by Lebanese law to prosecute former ministers Khalil, Zeaiter, and Fenianos, all of whom are lawyers. Both the Tripoli and Beirut Bar Association approved Bitar’s request to prosecute Khalil, Zeaiter, and Fenianos. As of July 29, 2021, parliament has still not lifted the immunity of these parliamentarians.

Bitar also requested permission to prosecute Major General Abbas Ibrahim, the Director General of General Security, from the Interior Minister, and he requested permission from Caretaker Prime Minister Hassan Diab to interrogate Major General Tony Saliba, the head of State Security, as a suspect. Judge Sawan had previously charged Saliba. On July 9, 2021, Caretaker Interior Minister Mohammad Fehmi refused Bitar’s request to prosecute Ibrahim, but Bitar appealed Fehmi’s decision and referred the case to the Cassation Public Prosecution. Cassation Attorney General Ghassan Khoury told Human Rights Watch that he denied Bitar’s request to prosecute Ibrahim. As of July 29, 2021, neither Prime Minister Diab nor President Aoun nor the Higher Defense Council had responded to Bitar’s request to interrogate Saliba as a suspect.

Bitar brought charges against former Lebanese Army Commander, General Jean Kahwaji, and three former senior officials in Military Intelligence.

The right to life is an inalienable right, enshrined in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) (article 6), which Lebanon ratified in 1972. The Human Rights Committee, which interprets the ICCPR, has stated that states must respect and ensure the right to life against deprivations caused by persons or entities, even if their conduct is not attributable to the state. The Committee further states that the deprivation of life involves an “intentional or otherwise foreseeable and preventable life-terminating harm or injury, caused by an act or omission.” States are required to enact a “protective legal framework which includes criminal prohibitions on all manifestations of violence…that are likely to result in a deprivation of life, such as intentional and negligent homicide.” They are also obligated to investigate and prosecute potential cases of unlawful deprivations of the right to life, and to provide an effective remedy for human rights violations.

Survivors of the explosion and the families of the victims have been vocal in calling for an international investigation, expressing their lack of faith in domestic mechanisms. They also argue that the steps taken by the Lebanese authorities so far are wholly inadequate to achieve accountability as they rely on flawed processes that are neither independent nor impartial.

As one year passes since the explosion, the case for such an international investigation has only strengthened. The Human Rights Council (HRC) has the opportunity to assist Lebanon to meet its human rights obligations by mandating an investigative mission into the August 4, 2020 explosion to identify the causes of, and responsibility for, the blast, and what steps need to be taken to ensure an effective remedy for victims.

The independent investigative mission should identify what triggered the explosion and whether there were failures in the obligation to protect the right to life that led to the explosion at Beirut’s port on August 4, 2020, including failures to ensure the safe storage or removal of a large quantity of combustible and potentially explosive material. It should also identify failures in the domestic investigation of the blast that would constitute a violation of the right to an effective remedy and the right to life. It should make recommendations on measures necessary to guarantee that the authors of these violations and abuses, regardless of their affiliation or seniority, are held accountable for their acts and to address the underlying systemic failures that led to the explosion and to the limited scope of the domestic investigation.

The independent investigative mission should report on the other human rights impaired or violated by the explosion and failures by the Lebanese authorities and make recommendations to Lebanon and the international community on steps that are needed both to remedy the violations and to ensure that similar violations do not occur in the future.

In addition, countries with Global Magnitsky and other human rights and corruption sanction regimes should sanction officials implicated in ongoing violations of human rights related to the August 4 blast and efforts to undermine accountability. Human rights and corruption sanctions would reaffirm states’ commitments to promoting accountability for perpetrators of serious human rights abuse and provide additional leverage to those pressing for accountability through domestic judicial proceedings.

Methodology

Human Rights Watch has compiled over 100 documents related to the Rhosus and its cargo, some of which have not been published before (See Annex 2 and English translations in Annex 3). These include documents sent to and from officials working under the Ministry of Finance, including customs officials; the Ministry of Public Works and Transport, including port officials; members of the judiciary; the Case Authority (a body at the Ministry of Justice that acts as the legal representative of the Lebanese state in judicial proceedings); members of the Higher Defense Council; General Security; State Security; and others. These documents were obtained via open-source research and from the investigative unit at Al-Jadeed television, the Samir Kassir Foundation, and six confidential sources.

Human Rights Watch wrote to 43 Lebanese government officials and six political parties regarding the role that they and their institutions played in the August 4, 2020 explosion and to eight companies and two law firms to request information pertaining to the Rhosus and its cargo and their work (see Annex 4). Six officials, one company, and one law firm responded to our correspondence on the record before publication and their responses have been incorporated into this report (see Annex 5).

For this report, Human Rights Watch also conducted ten interviews with Lebanese government, security, and judicial officials, including the caretaker prime minister, the director general of State Security, and the former head of the Case Authority. Human Rights Watch also interviewed three lawyers representing individuals who have been charged for the August 4 explosion at Beirut’s port, as well as seven of their relatives. In addition, we interviewed a lawyer representing a group of victims of the blast, a former shipping company employee, someone who saw the ammonium nitrate in hangar 12 in early 2020, an investigative journalist, a researcher with expertise in the structure of Beirut’s port, and seven people who were impacted by the August 4 explosion.

Most interviews were conducted in person, but some were conducted over the phone. Researchers informed all interviewees about the purpose and voluntary nature of the interviews and the ways in which Human Rights Watch would use the information and obtained consent from all interviewees. Human Rights Watch has withheld the names of some individuals featured in the report at their request. Interviews were conducted in Arabic or English without the assistance of a translator.

Human Rights Watch also reviewed local and international media and other reports related to the August 4 blast and Beirut’s port.

Port of Beirut: A Case Study in Lebanese Authorities’ Mismanagement and Corruption

The port of Beirut is Lebanon’s main commercial port and a hub for maritime trading on the Mediterranean Sea. In 2019, the port handled an estimated US$20 billion of trade, comprising 78 percent of Lebanon’s imports and 48 percent of its exports.[1] It has also played a significant role in transit traffic, especially to Syria and Iraq.[2]

However, Beirut’s port, sardonically referred to by some Lebanese as “the cave of Ali Baba and the 40 thieves,” has been rife with corruption, negligence, and mismanagement, and is emblematic of the failures of post-war state building and political sectarianism in Lebanon.[3]

From 1960 until 1990, Beirut’s port was managed by a private company, the ‘Compagnie d’Exploitation et de Gestion du Port de Beyrouth’ (CEGPB).[4] In 1990, after the end of the civil war, management of the port reverted to the state, as the company’s 30-year concession also ended in December 1990.[5] But, former warlords and political leaders who had a financial stake in how the port was managed could not agree on how to manage it, including whether the port should be a private or public institution.[6]

In 1993, the Council of Ministers established a provisional administrative body, the “Temporary Committee for Management and Investment of the Port of Beirut” (hereafter referred to as the Port Authority).[7] Its seven seats were divided among the country’s main political factions, thereby making the port’s management subject to power struggles between them, which in turn paralyzed decision-making.[8] The Port Authority, despite its intended temporary nature, has continued to operate to this day.

By default, the port became part of the state under the Port Authority, but it was operating without an institutional framework, which led to a scathing critique by the World Bank when it wrote:

[T]he Temporary Committee does not publish balance sheets or financial statements. It is not in itself a legal entity. The absence of a real port authority, coupled with mismanagement by the Temporary Committee have involved serious governance, transparency, and accountability issues. This has also resulted in a lack of focus on socioeconomic development, a lack of planning, poor safety and declining efficiency of operations.[9]

Dr. Reinoud Leenders, a researcher who has written a book about corruption and state building in post-war Lebanon, aptly explained how this structure is problematic:

The Ministry of Public Works and Transport came to ‘supervise’ the port, but it fell short of having the authority to effectively control it. The port’s dealings with the private sector suffered from legal problems as it lacked clear legal powers only a full-fledged state agency could exercise. As the port never appeared on any organizational chart stipulating political and administrative authority, its dealings with other state entities – such as the customs authority, security agencies and ministries – were left to the discretion and inclinations of politicians and officials involved. The port’s ambiguous legal status confused judges tasked to intervene in legal disputes involving it, more often than not prompting them to declare that they lacked jurisdiction or to endlessly pass on complex issues to other branches of the judiciary or state agencies. In a few cases where judges (mostly judges of ‘Urgent Matters’ responsible for immediate execution of court orders) did take a stand, politically backed port officials simply ignored or overruled them. Given its diffuse, contested and ambiguous institutional environment, the port was hit by corruption scandals as it provided ample opportunity for abuse and plenty of ambiguity to cover it up.[10]

Indeed, the port’s governance structure created the conditions for corruption and mismanagement to flourish.[11]

Lebanon’s main political parties, including Hezbollah, the Free Patriotic Movement, the Future Movement, the Lebanese Forces, the Amal Movement, and others, have benefited from the port’s ambiguous status and poor governance and accountability structures.[12] As described below, political parties have installed loyalists in prominent positions in the port, often positioning them to accrue wealth, siphon off state revenues, smuggle goods, and evade taxes in ways that benefit them or people connected to them.

A 2019 study by two Harvard academics found that 17 out of Lebanon’s 21 shipping line companies have links to politicians via their board members, managers, or shareholders.[13] In September 2020, AFP obtained a report, seen by Human Rights Watch, that named five customs officials who “cannot be replaced” and noted their political affiliations with the Free Patriotic Movement, the Future Movement, the Amal Movement, Hezbollah, and the Lebanese Forces, respectively.[14]

Bribery and petty crime have been rife at the port. A New York Times investigation enumerated the chain of kickbacks required to move cargo into and out of the port: “to the customs inspector for allowing importers to skirt taxes, to the military and other security officers for not inspecting cargo, and to Ministry of Social Affairs officials for allowing transparently fraudulent claims.”[15]

Riad Kobeissi, an investigative journalist who has been investigating corruption at the port for almost a decade, told Human Rights Watch that “the port was not intended as something that will bring in revenue to the state, but it acts to fill the pockets of the mafias running the country… therefore, in the port you appoint people whose job is not to collect money for state coffers, but to collect money for you.”[16]

Over the years, Kobeissi has filmed several customs officials alleging that they regularly receive bribes or actually receiving bribes, including in return for turning a blind eye to errors in declaration forms or circumventing the customs risk software, which determines the clearance track and levels of scrutiny over the goods.[17] In the majority of cases, those officials have not been held accountable.[18] Kobeissi has also uncovered multi-million dollar customs duty evasion schemes where politically-connected individuals, including the children of senior politicians, security officials, public servants, and judges, were able to purchase luxury items at significantly discounted prices without paying all the customs duties and registration taxes.[19]

Corruption at the port is so pervasive that in 2012, the Minister of Public Works and Transport estimated that the losses resulting from tax evasion at the port amounted to more than $1.5 billion per year.[20] Julien Courson, the head of the Lebanon Transparency Association, estimates that today Lebanon loses around $2 billion in customs revenue each year due to corruption.[21]

The mismanagement and corruption at the port has not only enriched party loyalists and others at the expense of the state, but it has also allowed illicit and dangerous goods to enter the country undetected. A former shipping company employee described to Human Rights Watch the security vacuum and web of bribery at the port that allows for dangerous goods to enter or leave the country without any monitoring. He said that companies or individuals who want to bring in any type of goods, including prohibited goods, can do so if they pay customs officials enough. He underscored that the state rarely, if ever, apprehends those goods.[22] “All of these busts that you hear about in the media are either the result of a targeted attack on someone, a betrayal, or an accident,” he said.[23]

In April 2019, the port’s main cargo scanner fell into disrepair, but it was never replaced, reportedly due to political considerations over who would get the contract, leaving all goods to be manually searched.[24]

Hezbollah in particular has been accused of using Beirut’s port for its own purposes. According to one former judicial official who spoke with AFP, Hezbollah has a “free pass” to transport goods at the port because of its ties to customs and port officials.[25] The United States government sanctioned Wafiq Safa, a Hezbollah security official, in 2019, asserting that he used “Lebanon’s ports and border crossings to smuggle contraband and facilitate travel on behalf of Hizballah, undermining the security and safety of the Lebanese people, while also draining valuable import duties and revenue away from the Lebanese government.”[26]

The Lebanese General Directorate of State Security, which is an arm of the Higher Defense Council chaired by the president, established an office at the port in April 2019 tasked with fighting corruption there.[27] The Director General of State Security, Major General Tony Saliba, told Human Rights Watch that “there was a battle to establish this office.”[28] He said all the other security agencies at the port, as well as customs and port officials, did not want State Security to be looking into corruption.[29] Saliba said that State Security wrote various reports on corruption at the port, including on the payment of bribes and the assigning of bids.[30]

Several major political parties in Lebanon have acknowledged the massive scale of corruption at the port, and particularly by customs, and blamed the state for failing to address it. For example, Hezbollah MP Hassan Fadlallah in May 2020 said:

The corruption and wastage at the customs, how many times did we speak about this? How many complaints and lawsuits have been filed? Until now, we haven’t seen anything substantive…the state is present, and its institutions are present. Let the state do its full duty at all its ports and border crossings, and if anyone obstructs it, it should do what it is legally necessary.[31]

Similarly, in late 2012, while President Michel Aoun was still heading the Free Patriotic Movement, he acknowledged the problems of smuggling and disorder at Beirut’s port, following an investigation aired by Al-Jadeed television. He said “I consider the state responsible for this smuggling, but not just in terms of negligence. Customs doesn’t have a director general.”[32] He blamed the state for failing to appoint a director general, and he said that this gap in leadership obstructed efforts at accountability.[33]

When Aoun became president in 2016, he vowed to “eradicate corruption.” [34] However, he has continued to support the director general of Lebanese Customs, Badri Daher, whom the Cabinet appointed on March 8, 2017, even though he has been accused of corruption.[35] In an interview on January 8, 2020, Gebran Bassil, Aoun’s son-in-law and the head of the Free Patriotic Movement, publicly acknowledged that the party backed Daher’s appointment.[36]

Daher has been charged for his role in the August 4, 2020 explosion and has been in detention since August 2020.[37] Although Daher promised to eradicate the practice of bribing customs officials when he took office, he has since been prosecuted multiple times for corruption.[38] Daher was prosecuted in November 2019 for “wastage of public funds” after investigative journalists uncovered transgressions within the Customs Administration and at the Beirut port, including with regard to public auctions he organized.[39] In 2020, he was also charged with unlawfully lifting a travel ban on Abdul Mohsen Bin Walid Bin Abdul Aziz al-Saud, a Saudi prince who had been detained in 2015 while attempting to smuggle 1.9 tonnes of Fenethylline, an amphetamine used in the prohibited drug Captagon, aboard his private jet.[40] Daher said President Aoun personally asked him to lift the ban.[41] The president’s office denied these claims in a tweet by the Lebanese Presidency Twitter account.[42] In October 2020, for the second time, Aoun refused to sign off on Daher’s dismissal from his post, following charges against the director in relation to the August 4, 2020 explosion, without a full Cabinet vote.[43]

In addition, despite promising to stamp out corruption at the port, the Minister of Finance between 2014 and 2020, Ali Hassan Khalil, a member of the Amal Movement, was sanctioned by the United States government for alleged material support to Hezbollah, including through corruption.[44] The Ministry of Finance oversees the Customs Administration, which controls the entry of goods into Lebanon including through the Beirut port.[45] The US sanctioned Khalil, in part, for allegedly using his position to exempt a Hezbollah affiliate from paying taxes on imports, noting that in 2019 he also allegedly refused to “sign checks payable to government suppliers in an effort to solicit kickbacks.”[46]

In September 2020, the US government also sanctioned Youssef Fenianos, a member of the Marada Movement, who was the Minister of Public Works and Transport between 2016 and 2020, for alleged material support to Hezbollah, including through corruption.[47] The Ministry of Public Works and Transport oversees the port. The US government statements on the sanctions asserted that Fenianos used his position as minister to funnel money from government budgets to Hezbollah-owned companies and diverted ministry funds to “offer perks to bolster his political allies.”[48]

The general inefficiency, mismanagement, corruption, and political malfeasance that has plagued the Beirut port for decades all contributed to the devastating blast there on August 4, 2020.

The Rhosus: Arrival in Beirut

The widely reported narrative regarding the arrival of the Rhosus, a Moldovan-flagged ship, in the port of Beirut in November 2013 carrying 2,750 tonnes of high-density ammonium nitrate is as follows: the ship’s cargo was ultimately bound for Mozambique; it entered Beirut’s port to load seismic equipment it was then meant to deliver to Jordan before traveling onward to Mozambique; the ship’s owner was a Russian national, Igor Grechushkin; and the owner of the ammonium nitrate on board, Savaro Limited, was a chemical trading company in the United Kingdom. [49] Upon examination, however, it is not clear that any of these assertions are true.

In fact, the Rhosus was rented to transport an estimated 160 tonnes of seismic equipment when it was already overloaded and not equipped to do so. While Savaro Limited is registered in the UK, reporting by investigative journalist Firas Hatoum indicates that it’s a shell company that shares a London address with other companies linked to two Syrian-Russian businessmen who have been sanctioned by the US government for acting on behalf of the Syrian government of President Bashar al-Assad. The identity of Savaro Limited’s beneficial owner is unknown. The identity of the actual owners of the ship has also been in question. At least until shortly after its arrival in Beirut’s port, the ship was owned by an individual who had links to a bank accused of having dealings with the Syrian government and Hezbollah.

Once the ship arrived in Beirut, evidence suggests officials failed to disclose the potentially explosive and combustible nature of the ship’s cargo, and the danger it posed, and inaccurately described its risks in their requests to the judiciary to offload the merchandise (see section on “Ministry of Public Works and Transport” below).

That evidence, combined with evidence suggesting the ammonium nitrate was being siphoned off from the port, the clear inability of the Rhosus to perform the task it was hired to do, the lack of clarity regarding the ownership of both the ship and its cargo, and the half-truths that contributed to the offloading of the ammonium nitrate into hangar 12, raises questions regarding whether the ammonium nitrate was intended for Mozambique as the Rhosus’s shipping documents stated or whether there were individuals with control of the cargo and ship who wanted the ammonium nitrate to remain in Beirut.

Beirut Port: An Ill Fated or Planned Destination?

The Rhosus arrived in Beirut carrying 2,750 tonnes of high-density ammonium nitrate.[50]

According to the ship’s captain, Boris Prokoshev, the Rhosus docked in Beirut after Igor Grechushkin, a Russian national described as the ship’s owner or operator, ordered him to make a last-minute stop in Beirut, to pick up additional cargo to be used to pay for passage through the Suez Canal.[51] The Rhosus was set to carry the additional cargo—seismic survey equipment, which included trucks and was estimated to weigh up to 160 tonnes—from Beirut’s port to Jordan.[52] Experts have noted, however, that the Rhosus was not a “roll-on/roll-off ship,” and would not have usually been used to transport vehicles.[53] Additionally, the ship was already at capacity.[54]

Indeed, while attempting to load the cargo, the ship’s hatches covering the ammonium nitrate began to buckle under the cargo’s weight because the ship’s maximum capacity had already been exceeded.[55] When the ship docked in Beirut’s port, the ship was also found to not be seaworthy.[56] Making matters worse, there were outstanding debts against the ship, causing it to be impounded by Lebanon’s Enforcement Department on December 20, 2013.[57]

The seismic survey equipment that the Rhosus was supposed to load in Beirut was in Lebanon as a result of a contract between Spectrum, a UK company, and then-Minister of Energy and Water Gebran Bassil.[58] Letters from Bassil to Lebanese customs officials reflect that Spectrum had subcontracted “GSC,” or Geophysical Services Center, a Jordanian company, to do the work, and that Spectrum’s agent in Lebanon was Cogic Consultants.[59]

Cogic Consultants wanted to move the equipment it had used during the oil and gas exploration missions for the minister back to Jordan, since the equipment was owned by GSC.[60]

The Spectrum employee who is reported to have signed the contract with Minister Bassil told the media that Spectrum subcontracted the movement of machinery.[61]

Human Rights Watch wrote to each of the companies involved to ask whether they selected the ship to transport the seismic equipment to Jordan, and if so, on what basis they made the selection but did not receive any on the record responses.

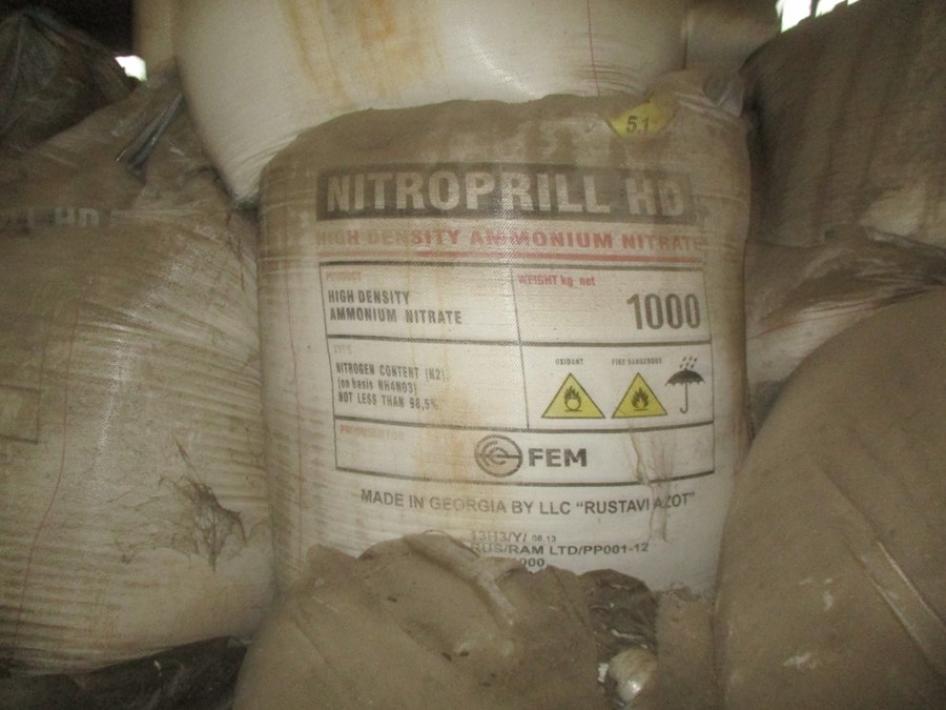

Another UK company, Savaro Limited, owned the ammonium nitrate, which it purchased from a Georgian chemicals factory, Rustavi Azot.[62]

While Savaro Limited is registered as a chemical trading company in the UK, in January 2021, investigative journalist Firas Hatoum revealed that it was a shell company, and that the company shared a London address with other companies linked to two Syrian-Russian businessmen who have been sanctioned by the US government for acting on behalf of the Syrian government of President Bashar al-Assad. [63] One of the men was sanctioned by the US government in 2015 for “materially assisting, sponsoring, or providing financial, material, or technological support for, or goods or services in support of his brother,” who was previously sanctioned by the US government for “an attempted procurement of ammonium nitrate in late 2013.”[64]

Two British lawmakers called for the company to be investigated in early 2021, after a media investigation revealed that the beneficial owner registered with the government was acting as an agent for the ultimate beneficial owner who had not been disclosed.[65]

Human Rights Watch wrote to Savaro Limited on July 8 and asked about its ownership, scope of business, relationship to the 2,750 tonnes of high-density ammonium nitrate on board the Rhosus, and what actions it took to retrieve its cargo. The company did not respond to the correspondence prior to publication.

Further, while it was widely reported that the Rhosus was owned by Grechushkin, the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCPR) reported that Cypriot documents listed the true owner as Charalambos Manoli. Manoli has publicly denied being the owner, saying that before the Rhosus’s last voyage, he transferred all the shares in Briarwood Corporation, which owned the Rhosus, to Grechushkin.[66] In a communication with Human Rights Watch, Manoli shared , on a confidential basis, contracts and other documents between Briarwood Corporation and Teto Shipping, that he said showed that possession and control of the Rhosus was transferred to Teto Shipping in 2012, before the Rhosus’s voyage, and that the shares of Briarwood were handed over to Grechushkin on November 28, 2013—while the ship was docked in Beirut’s port. Human Rights Watch was unable to verify the authenticity of the documents before this report went to publication.

OCCPR also reported that at the time of the ship’s last journey, Manoli reportedly owed nearly a million dollars to FBME, a Lebanese-owned bank sanctioned by the US government in 2014.[67] Manoli has publicly denied this, and denied it in his communication to Human Rights Watch, stating that the debt was paid by the time of the ship’s last voyage and that in 2018 a court dismissed proceedings that FBME had brought against him and companies he had an interest in.[68] Human Rights Watch was unable to verify these statements before publication.

FBME was sanctioned, in part, for allegedly facilitating the activities of international terrorist financiers, including for Hezbollah, and for having a customer that was a front company for a US-sanctioned Syrian entity, which was designated as a proliferator of weapons of mass destruction.[69]

Finally, some experts have called into question whether there were 2,750 tonnes of ammonium nitrate in hangar 12 when it exploded on August 4, 2020, estimating that the amount that remained in the hangar at the time of the explosion may have been 700-1,000 tons.[70] In an interview with Human Rights Watch on June 8, 2021, Caretaker Prime Minister Hassan Diab also said that according to the US Federal Bureau of Investigations (FBI) report, only 500 tons of ammonium nitrate exploded on August 4, 2020.[71] However, two experts who spoke to the New York Times said that based on their calculations most or all of the ammonium nitrate remained in the hangar and detonated.[72] Human Rights Watch also interviewed someone who saw the ammonium nitrate in hangar 12 in early 2020 and raised questions regarding whether there were still 2,750 bags of the material in the hangar, noting that the 5,000 square meter hangar should have been fuller if there were 2,750 bags, 1 square meter each, in the space.[73] However, he noted that some of the bags were stacked on top of each other, so it would have been hard for him to estimate the number of bags in the hangar.[74]

On October 1, 2020, Lebanon asked Interpol to issue arrest warrants for Igor Grechushkin and Boris Prokoshev, the Rhosus’ s captain.[75]

Excusing the Failure to Correctly Identify the Cargo

Ships carrying freight are issued a bill of lading, which is an official document between the shipper and the carrier that includes details of the shipment itself. The Rhosus’s Bill of Lading issued on September 23, 2013 in Batumi, Georgia identifies the goods on board the ship as 2,750.4 tonnes of high density ammonium nitrate IMO 5.1 in 2,750 “big bags.”[76] IMO 5.1 is a hazard classification under the International Maritime Organization shipping standards.[77] The Rhosus cargo manifest, dated September 27, 2013, lists the same description of the goods.[78]

While the maritime agent, the National Trading and Shipping Agency, a Lebanese company, identified the cargo on the transit manifest they prepared on November 16, 2013 as “2755.500 tons of High-Density Ammonium Nitrate,” they incorrectly identified it as IMO 5.0, not IMO 5.1.[79] However, they correctly identified the cargo on the “Notice and Recognition” form of the ship’s arrival, which they sent to the Customs Manifest Detachment.[80] A maritime, or shipping, agent is responsible for managing the transactions of a ship in port.[81]

After the ship docked in Beirut, however, officials in the Manifest Department at the General Directorate of Customs determined that the maritime agent incorrectly excluded a description of the ship’s cargo on the Unified List they prepared, which they said was a customs violation.[82] Riad Kobeissi, an investigative journalist who has been investigating corruption at the port, noted that the Unified List is akin to a ship’s “passport” and was used by security agencies to identify whether any cargo included prohibited or monopolized goods, thus warranting further scrutiny.[83] Yet, customs officials excused this violation without a proper investigation and despite having been alerted to the dangerous nature of the ammonium nitrate on board the ship by a customs official, on February 21, 2014.[84]

On February 22, 2014, having been alerted the day before about the dangerous nature of the ammonium nitrate on board the ship by a customs official, the Manifest Department at the General Directorate of Customs sent a letter to the National Trading and Shipping Agency requesting the agency appear before the department to explain why they did not describe the nature of the cargo on the ship’s Unified List.[85]

In its response to the Manifest Department on February 28, 2014, the agency claimed that as far as they knew, the Unified List only had to mention the quantity, weight, and destination country of the cargo and requested an exemption from the violation.[86] They added that they provided a copy of the ship’s transit manifest, which includes all the information about the ship’s cargo, to the Customs Manifest Detachment.[87]

The head of the Manifest Department then asked the head of the Beirut Brigades, which is a security entity under the General Directorate of Customs and supervises the Manifest Detachment, whether the ship’s transit manifest was shown to the Beirut Brigades and whether the manifest correctly identified the material on board, as the customs law requires.[88] The head of the Beirut Brigades reportedly refused to receive this request for information.[89] The Manifest Department then escalated the issue to the Customs Regional Directorate of Beirut, who once again “invited” the Beirut Brigades to submit the required information.[90]

The Manifest Detachment (under the Maritime Section, which is under the Beirut Brigades) then responded on March 31, 2014, saying that the Rhosus’s captain provided them with the Unified List, and then several days later provided them with the transit manifest, upon the request of the head of the Maritime Section. In his response, the head of the Manifest Detachment refers to a customs regulation (26036/2004; December 16, 2004) from the General Directorate according to which the manifest for cargo remaining on board a ship does not need to be shown unless there is information about the presence of prohibited or monopolized goods on the ship not declared on the Unified List, and after obtaining approval from the Director General of Customs.[91]

On April 1, 2014, the head of the Maritime Section, then-Captain Nidal Diab, who supervises the Manifest Detachment, sent this report to the head of the Beirut Brigades, adding that the type of merchandise on the Rhosus was not considered “prohibited or monopolized,” but it may be used “in certain proportions to produce prohibited substances, and it is considered a hazardous, restricted substance if used locally.”[92]

He cites a document that states that “ammonium nitrate with a nitrogen grade of 34.5% or less is no longer subject to the provisions of legislative decree no. 137/59 [Weapons and Ammunition Law], since it is not an ingredient in the manufacturing of explosives…”[93]

This report was sent to the Acting Head of the Beirut Brigades Colonel Ibrahim Shamseddine, who referred it on the same day to the Acting Head of the Regional Directorate of Beirut Moussa Hazimeh, who referred it to the Head of the Port of Beirut Service, who duly referred it to the Head of the Manifest Department on April 9, 2014.[94]

On April 22, 2014, based on the information above, the head of the Manifest Department at the time, Badri Daher, recommended excusing the violation of not identifying the type of cargo on the Unified List, saying it was correctly identified on the transit manifest.[95] On May 6, 2014, the head of the Customs Regional Directorate of Beirut approved Daher’s recommendation.[96]

However, it is not clear on what basis Diab identified the nitrogen content of the ammonium nitrate as being below 34.5 percent, as the samples were not analyzed until February 2016, when it was found that the nitrogen grade of the ammonium nitrate was in fact 34.7 percent.[97] The Weapons and Ammunition Law states that ammonium nitrate with a nitrogen grade of 33.5 percent or more is covered as another form of gunpowder and explosive material and, as such, its procurement, assembly, trade, and possession in Lebanon is restricted.[98]

Under the Customs Law, restricted merchandise is not allowed to be imported or exported without a license, permit, or special approval issued by a competent authority, which lifts the restriction on this merchandise, and any such merchandise without the relevant permits must be treated like prohibited goods and should be seized.[99] The law further states these restrictions could apply to goods in transit.[100]

The Lebanese army is responsible for giving prior approval for importing military equipment and ammunition, including ammonium nitrate with a nitrogen grade above 33.5 percent, and must inspect explosive substances that arrive to the country through its ports (see section on the “Lebanese Army” below), but there is no indication that they did so in this case, even after testing confirmed that the material fell under the scope of the Weapons and Ammunition Law.

State Negligence or Malfeasance? February 2014-August 2020

Official responsibility for the Beirut port is shared between the Ministry of Public Works and Transport, which oversees the Port Authority, and the Ministry of Finance, which oversees the Customs Administration. Within customs, two parallel institutions govern: the Higher Council for Customs and the General Directorate of Customs. Responsibilities between these and other government and security agencies operating in the port are overlapping (see “Port of Beirut: Mismanagement and Corruption” section above). In addition, a range of security services are also present at the port with overlapping mandates, including from the Lebanese Armed Forces (Military Intelligence), State Security, General Security, and customs.[101]

The legal and regulatory framework governing the port is outdated and inefficient, and the port’s ambiguous legal status has created confusion regarding which judges have jurisdiction to rule on matters related to the port.[102] The World Bank, in a December 2020 report on governance over Beirut’s port, concluded that the port “is a patchwork of ad-hoc institutions, structures, laws and regulations” that is inefficient, subject to political exploitation and corruption, opaque, and one which has resulted in serious governance and accountability issues.[103] The World Bank correctly identifies the mismanagement and lack of accountability in the Beirut port as having contributed to the August 4 explosion.[104]

This section reviews the decisions (and often, inaction) of government officials concerning the Rhosus and its cargo between February 2014 and the explosion on August 4, 2020, breaking down the actions of each government ministry or agency operating in the Beirut port. An analysis of government documents and interviews conducted by Human Rights Watch indicates that multiple Lebanese authorities were, at a minimum, criminally negligent under Lebanese law in their handling of the Rhosus’s cargo.[105] Their actions and omissions created an unreasonable risk to life. Under international human rights law, a state’s failure to act to prevent foreseeable risks to life is a violation of the right to life.[106]

In addition, evidence strongly suggests that some government officials foresaw the death that the ammonium nitrate’s presence in the port could result in and tacitly accepted the risk of the deaths occurring.[107] Under domestic law, this could amount to the crime of homicide with probable intent, and/or unintentional homicide.[108] It also amounts to a violation of the right to life under international human rights law.[109]

Official correspondence reflects that once the ship arrived in Beirut, Ministry of Finance (see section on “Excusing the Failure to Correctly Identify the Cargo” above) and Ministry of Public Works and Transport officials failed to correctly communicate or adequately investigate the potentially explosive and combustible nature of the ship’s cargo, and the danger it posed. Ministry of Public Works and Transport officials inaccurately described the cargo’s risks in their requests to the judiciary to offload the merchandise and knowingly stored the ammonium nitrate in Beirut’s port alongside flammable or explosive materials for nearly six years in a poorly secured and ventilated hangar in the middle of a densely populated commercial and residential area (see “Ministry of Public Works and Transport Section” below). Their practices contravened international ammonium nitrate safe storage and handling guidance. Neither they, or any security agency operating in the port, took adequate steps to secure the material or establish an adequate emergency response plan or precautionary measures, should a fire break out in the port. They also reportedly failed to adequately supervise the repair work undertaken on hangar 12 which may have triggered the explosion on August 4, 2020 (see section on “August 4, 2020” below).

Official correspondence also indicates that port, customs, and army officials ignored steps they could have taken to secure or destroy the material.

Customs officials repeatedly took steps to sell or re-export the ammonium nitrate that were procedurally incorrect. But instead of correcting their procedural error, they persisted with these same incorrect interventions despite repeatedly being told of the procedural problems by the judiciary. Legal experts even state that customs officials could have acted unilaterally to remove the ammonium nitrate and that they could have sold it at public auction or disposed of it without a judicial order, which they never took steps to do (See “Ministry of Finance” section below).

The Lebanese Army Command brushed off knowledge of the ammonium nitrate in hangar 12, saying they had no need for the material, even after learning its nitrogen grade classified it under local law as material used to manufacture explosives and required army approval to be imported and inspection. Despite being responsible for all security issues related to munitions at the port and being informed of the ammonium nitrate in hangar 12, Military Intelligence took no apparent steps to secure the material or establish an appropriate emergency response plan or precautionary measures (see section on the “Lebanese Army” below).

All of this was done despite repeated warnings about the dangerous nature of ammonium nitrate and the devastating consequences that could follow from its presence in the port.

Even after security officials from the Lebanese General Directorate of State Security, an arm of the Higher Defense Council chaired by the president, completed an investigation into the ammonium nitrate at the port, there was an unconscionable delay in reporting the threat to senior government officials, and the information they provided about the threats posed by the material was incomplete (see “State Security” section below).

Both the then-Minister of Interior and the Director General of General Security have acknowledged that they knew about the ammonium nitrate aboard the Rhosus, but have said that they did not take action after learning about it because it was not within their jurisdiction to do so.

Once they were informed by State Security, other senior officials on Lebanon’s Higher Defense Council, including the president and the prime minister, also failed to act to remove the threat (see “Higher Defense Council” section below).

Ministry of Public Works and Transport

Representatives of the Ministry of Public Works and Transport were warned about the serious danger presented by the ammonium nitrate, yet failed to investigate the threat the material posed and mischaracterized what they were told about the danger in their communications with the Case Authority.

The Case Authority falls under the Directorate General of the Ministry of Justice per Legislative Decree 151/1983 (later amended by Decree 23/1985). It acts as the legal representative of the Lebanese State in all judicial and administrative proceedings, with the Minister of Justice assigning judges and lawyers to assist the judge presiding over the Case Authority.[110]

Based on the incorrect information the ministry provided to the Case Authority, the judge of urgent matters subsequently ordered that the ministry offload the ship’s cargo. After the cargo was offloaded, the ministry continued to misrepresent the danger it posed.

Further, ministry officials failed to properly execute a June 27, 2014 judicial ruling to store the ammonium nitrate in a suitable place and to take the necessary precautions in doing so. Instead, they knowingly stored the ammonium nitrate in hangar 12 alongside flammable or explosive materials for nearly six years in a poorly secured and ventilated hangar in the middle of a densely populated commercial and residential area. Their practices contravened international ammonium nitrate safe storage and handling guidance. They also failed to take adequate steps to secure the material or establish an adequate emergency response plan or precautionary measures should a fire break out in the port.

All of the actions taken by ministry officials appear to have been limited to seeking court approval to sell or re-export the ammonium nitrate and appear to have excluded measures they could have taken to store the dangerous material in a secure manner. Even the attempts to sell or re-export the cargo were badly managed, resulting in unnecessary delays and the continued presence of the hazardous material in Beirut’s port.

Finally, they also reportedly failed to adequately supervise the repair work undertaken on hangar 12 that may have triggered the explosion on August 4, 2020 (see section on “August 4, 2020” below).

Failure to Investigate and Communicate the Danger

On April 7, 2014, Baroudi and Associates Law Firm, representing the captain of the Rhosus, Boris Prokoshev, addressed a letter to the “head of Beirut’s port,” and delivered and registered it at the Directorate of Land and Maritime Transport, which falls under the Ministry of Public Works and Transport, on April 9.[111] The firm, which was seeking the repatriation of the ship’s crew to Russia and Ukraine, urged that the ministry take all necessary measures to avoid “a maritime catastrophe,” and to sell the ship and its cargo to pay the debts owed to the crew and others.[112]

In this letter, the firm states that ammonium nitrate is “considered an extremely hazardous material due to its high flammability and because it is used in the manufacture of explosives” and that as a result it “requires taking due diligence and precaution while stocking or moving it.”[113] They further state that “the interaction of ammonium nitrate with water exposes the cargo to the risk of explosion.”[114] The lawyers attach a 16-page “Timeline of major disasters” caused by ammonium nitrate explosions.[115]

Some of the information provided by the firm incorrectly described the risks posed by the cargo. Ammonium nitrate is non flammable, but it can cause combustible materials to ignite, and under extreme conditions of heat and pressure in a confined space it will explode.[116] It can be used to make explosives but is principally used as a fertilizer.[117] While ammonium nitrate is hygroscopic, meaning it absorbs moisture, and water absorption does cause it to decompose, degrade and become more unstable, mixing it with water would not on its own have exposed the cargo to the risk of explosion.[118]

On July 8, 2021, Human Rights Watch wrote to Baroudi and Associates asking how they first became aware of the ammonium nitrate on board the Rhosus and the dangers that the cargo posed. Baroudi and Associates responded on July 12, 2021, saying that they are legally prohibited from answering the questions.

Further, the Beirut harbor master, Mohammad al-Mawla, sent two letters in 2014, one of which was addressed directly to Abdel Hafiz al-Kaissi, director general of Land and Maritime Transport, warning that the ammonium nitrate on board the Rhosus was hazardous and that the ship was at risk of sinking, and requesting further instructions on how to proceed.[119]

Correspondence between Baroudi and Associates, the Ministry of Public Works and Transport, the Case Authority, and a Beirut judge of urgent matters, suggests that the ministry did not undertake any investigation into the danger posed by the ammonium nitrate, and instead shared only a portion of the information they received with the Case Authority that implied that the risk the material posed would be neutralized if it were offloaded from the ship. Even after the cargo was offloaded, the ministry continued to incorrectly represent the dangers presented by the material.[120]

After receiving the April 7, 2014 letter from Baroudi and Associates Law Firm, al-Kaissi responded on April 17, fully reciting the risks identified by the firm.[121] In contrast with his letter to the firm, in his correspondence with the Case Authority he fails to note that ammonium nitrate is potentially explosive, that it can be used to make explosives, and that it must be secured, instead focusing only on the risk of the ship sinking with the cargo onboard. On April 8 and April 14, 2014, he requested that the Rhosus be sold at public auction to avoid it sinking with its dangerous cargo which, as he states in the April 8 letter, would pollute the seawater and obstruct maritime traffic, and, as he writes in the April 14 letter, “threatens the safety of the maritime navigation and ecosystem in the port.”[122]

On June 2, 2014, he writes that if the ship sinks, it could cause an explosion due to the hazardous material on board.[123] He does not relay other information contained in the April 7, 2014 letter from Baroudi and Associates law firm, including that ammonium nitrate is used to manufacture explosives; that it has caused devastating explosions, resulting in hundreds of deaths; and that precautions must be taken while storing or moving it.[124]

Al-Kaissi also sends the Case Authority a report prepared by the Ship Inspection Service.[125]

On April 2, 2014, the Ship Inspection Service staff under the Directorate General of Land and Maritime Transport, had inspected the Rhosus and concluded conditions on the ship had deteriorated and it was at risk of sinking. Captain Haitham Chaaban of the Inspection Services recommended the ship leave Lebanese waters, noting it was a hazard for the safety of maritime navigation and a water pollution risk. He noted the cargo was dangerous and could potentially cause a chemical reaction, could expire, or could leak into the sea.[126] The report did not reflect that the material is a combustible chemical compound or that it can be used for explosives.

After receiving al-Kaissi’s request, the Case Authority appointed Omar Tarabah to represent the Ministry of Public Works and Transport in the matter.[127] On April 30, 2014, Tarabah sent a letter to the judge of urgent matters regarding the Rhosus. In the correspondence, he reiterated the dangers outlined by al-Kaissi and by the Ship Inspection Service’s report, stating that the ship was leaking and in danger of sinking, that it is carrying ammonium nitrate, which is a hazardous substance, and that its cargo could trigger a chemical reaction that would lead to “environmental pollution.”[128] He requested that the judge give the Directorate General of Land and Maritime Transport the authorization to refloat the ship, transport the ammonium nitrate to a safe place and guarantee its security, and sell the ship and the cargo in order to settle the debts incurred by the ship’s owners.[129]

Following the April 30, 2014 petition, on May 7, a judge of urgent matters appointed the court’s clerk to investigate the matter and to take a statement from the ship’s owners, the maritime agent, and the captain.[130]

On June 2, al-Kaissi reiterated the urgency of the request to sell the ship to the Case Authority, noting the dangers of it sinking but once again failing to mention other risks posed by the material, including that it is potentially explosive and combustible and that it can be used to make explosives.[131] On June 5, the Case Authority wrote to the judge of urgent matters again, asking the latter to authorize the requested measures as soon as possible.[132]

On the basis of the inaccurate and incomplete information that the Ministry of Public Works and Transport provided, on June 27, 2014, a judge of urgent matters ordered that the Rhosus’s cargo be offloaded from the ship.

The judge’s June 27, 2014 ruling authorized the Ministry of Public Works and Transport to refloat the ship after “moving the material onboard and storing it in an appropriate place under its custody, after taking the necessary measures given the hazardous material onboard the ship.” The judge refused to authorize the sale of the ship for lack of jurisdiction. He appointed the court's clerk to enforce the ruling.[133]

The Case Authority was informed of the decision on July 11, 2014 through Tarabah, who requested that the Case Authority inform the Directorate General of Land and Maritime Transport.[134] The General Directorate of Customs and the Directorate General of Land and Maritime Transport were also informed on September 26, 2014 of the judge’s decision.[135]

The cargo was offloaded into hangar 12 in the port in October 2014. After the cargo was offloaded, correspondence between the Ministry of Public Works and Transport and the Case Authority continued to mischaracterize the threat posed by the ammonium nitrate.

Ghazi Zeaiter was the Minister of Public Works and Transport from February 2014 until December 2016.[136] He was replaced by Youssef Fenianos, who held the position until January 2020.[137]

Zeaiter was informed about the ammonium nitrate on at least two occasions. The Director General of General Security, Major General Abbas Ibrahim sent Zeaiter a letter on May 16, 2014 informing him of the presence of “several tonnes of a very dangerous substance,” high density ammonium nitrate, on board the Rhosus.[138] Zeaiter also received an August 20, 2014 letter from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Emigrants attaching the June 27, 2014 ruling by the judge of urgent matters authorizing the ministry to refloat the ship after “moving the material onboard and storing it in an appropriate place under its custody, after taking the necessary measures given the hazardous material onboard the ship.”[139]

As minister, Fenianos sent letters to the Case Authority regarding the ammonium nitrate at the port on December 18, 2017, March 5, 2018, and September 12, 2018, asking the Case Authority to ask the Enforcement Department to take the necessary steps to sell the ship and cargo or re-export the materials.[140]

The letters reference the danger posed by the sinking ship to maritime navigation (correspondence from the minister on March 5, 2018 reflects that the Rhosus did sink on February 18, 2018), public safety, and the environment, but are silent on the dangers posed by the ammonium nitrate stored in hangar 12.[141] Instead, Fenianos highlighted the costs that had been incurred from moving and storing the ammonium nitrate at the port and requested that the Enforcement Department take the necessary measures to sell the ship and the ammonium nitrate at public auction or re-export the cargo.[142]

After the August 4, 2020 explosion, Fenianos said he personally signed eight letters regarding the ammonium nitrate and the Directorate General of Land and Maritime Transport sent another eight.[143] Human Rights Watch has obtained three letters the Ministry of Public Works and Transport sent to the Case Authority before the cargo was unloaded and four from after, three of which were signed by the minister.[144] None of these letters accurately describe the risk posed by the ammonium nitrate at the port. Human Rights Watch also wrote to Fenianos to request copies of the letters he referenced but did not receive a response prior to publication.

Michel Najjar, the Minister of Public Works and Transport at the time of the blast, said in the days following the blast that he learned that since 2014, the ministry had sent at least 18 letters to the Beirut judge of urgent matters asking that the ammonium nitrate be disposed of.[145] None of these letters came from Najjar, who was alerted to the dangers posed by the ammonium nitrate on August 3, 2020, the day before the explosion, when he received a copy of a State Security report outlining the threat.[146] Upon receiving the letter, Najjar reportedly instructed his advisor to contact Hassan Koraytem, the port’s director general, and request all relevant documents from him.[147] In a letter to Najjar on July 7, 2021, Human Rights Watch asked the caretaker minister to provide information about the communication with Koraytem. He did not respond to the correspondence prior to publication.

Journalists from the local television station Al-Jadeed presented evidence that an advisor to Najjar removed documents from the Ministry of Public Works and Transport on August 9, 2020, the Sunday following the blast. Najjar and his advisor gave conflicting accounts of what those documents were on live television.[148] In its correspondence, Human Rights Watch asked Najjar about the nature of the documents but did not receive a response.

Failure to Store the Ammonium Nitrate in a Secure Manner

The judge’s June 27, 2014 ruling called on the Ministry of Public Works and Transport to store the ammonium nitrate in an “appropriate place under its custody, after taking the necessary measures given the hazardous material onboard the ship.”[149] In clear contravention of this, ministry officials stored the ammonium nitrate in a poorly secured hangar in Beirut’s port alongside flammable and other hazardous material in a congested and haphazard way, just a few hundred meters from a densely populated residential area.

The judge appointed the court's clerk to enforce the ruling in his June 27, 2014 decision.[150] But according to an Al-Jadeed television news report, when the clerk went to the port on June 27 to examine the cargo, authorities told him they wanted to delay the removal of the cargo from the ship until a future date.[151] When he returned on the agreed date, November 13, 2014, it had already been placed in hangar 12 at the port.[152]

Following the judicial decision, on September 3, 2014, in a letter addressed to the port authority, Al-Kaissi requests the assignment of a location for the cargo to be stored. Al-Kaissi wrote that the material was hazardous, but did not specify the dangers posed by the ammonium nitrate.[153]

Koraytem assigned part of the hangar “designated for the storage of hazardous substances” as the location for the ammonium nitrate to be stored, and on October 23 and 24, 2014, the Port Authority, along with two companies, transferred the ammonium nitrate from the Rhosus to hangar 12.[154]

On November 13, 2014, the court’s clerk appointed Mohammad al-Mawla, the Beirut harbor master, as the “judicial guard” of the cargo in hangar 12, as he was the representative of the General Directorate of Land and Maritime Transport in the port, which had petitioned the court to transfer the material.[155] The judicial guard would bear legal responsibility if the material were damaged or went missing. However, al-Mawla signed with reservations, stating that he has no authority over the warehouses, as they are under the authority of the customs administration and the port authority.[156]

On November 26, 2014, al-Kaissi once again asked the Case Authority to “take all the necessary measures” to sell the Rhosus and its cargo under auction “in a prompt and immediate manner” because the ship was at risk of sinking, which would pose a danger to the maritime environment.[157] In a response, Omar Tarabah, the lawyer acting on behalf of Case Authority, stated that the ministry had failed to properly and fully implement the June 27 decision of the judge of urgent matters, because they were supposed to refloat the ship and transport the hazardous goods to an appropriate place for storage, and therefore the danger should have ceased.[158] There is no apparent response to this letter from the ministry.

Hangar 12 is a warehouse designated for hazardous and flammable materials. At the time of the explosion, the ammonium nitrate was reportedly stored alongside kerosene, hydrochloric acid, 23 tons of fireworks, 50 tons of ammonium phosphate, and 5 rolls of slow burning detonating cord, among other items.[159] In September 2020, the New York Times reported, “Bags of ammonium nitrate were piled haphazardly near the fuel and fuses and on top of some of the fireworks.”[160] The facility was not adequately guarded (see “State Security” section below).[161]

The Ammunition Management Advisory Team (AMAT), which is an initiative of the Geneva International Center for Humanitarian Demining (GICHD) and the United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs (UNODA) and provides guidance on the implementation of the International Ammunition Technical Guidelines (IATG), warns that ammonium nitrate can “react violently with incompatible materials” and that it is therefore “very important to handle, store and monitor ammonium nitrate correctly.”[162] They recommend that ammonium nitrate be stored in well-ventilated spaces away from sources of heat, fire, and explosion, including fuels and fireworks, and other combustible materials such as wooden pallets.[163]

The national regulations of several countries, including the United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, and the United Sates, concerning ammonium nitrate storage and handling requirements, also prohibit the storing of explosive and combustible material in proximity to ammonium nitrate.[164]

The concentrated storage of the ammonium nitrate in Beirut’s port and the storage facility’s proximity to residential areas also contravened safe storage and handling standards. AMAT guidance states that ammonium nitrate stacks should be no more than two meters high and three meters wide, and there should be at least one-meter-wide aisles between the ammonium nitrate stacks and between the stack and the walls of the storage building. AMAT estimated that based on the amount of ammonium nitrate in Beirut’s port, the closest inhabited building should have been 2,292 meters away, instead of the 480 meters distance that they were.[165] According to UK standards, stacks of ammonium nitrate must be limited to 300 tonnes with at least one meter between stacks.[166] Australian standards state that stacks can be 500 tonnes but should be 890 meters away from the closest residential buildings.[167]

Al-Kaissi, while aware of Koraytem’s selection of hangar 12 to store the ammonium nitrate, took no action to remove the material to another facility.[168] This is despite the fact that al-Kaissi had been warned by Baroudi and Associates that the material was dangerous and had caused devastating explosions in other parts of the world.

International guidance on safe storage and handling of ammonium nitrate also calls for authorities to develop an appropriate emergency response plan and safety precautions, should a fire break out in the port. [169] However, Human Rights Watch has uncovered no evidence that port authorities developed such a plan or precautions at any point between October 23-24, 2014 and the August 4, 2020 explosion.

The danger of storing ammonium nitrate in hangar 12 at the port was immediately clear. In October 2014, while the cargo was being offloaded, Nehme Brax, the head of the Manifest Department at the port, sent a letter to his superior, Hanna Fares, the head of the Port of Beirut Service, recommending the ammonium nitrate be handed over to the Lebanese Army or re-exported “to avoid any potential disaster resulting from the ignition of the material, and given that their storage requires special facilities that are not available on the port premises.”[170] He adds that “it remains a duty to bring the dangerousness of the matter to the attention of the judge of urgent matters.”[171]

A July 20, 2020 State Security report on the ammonium nitrate in hangar 12 also concluded that port officials were negligent by not securing hangar 12 “which made it easy for individuals to go in and out and steal the dangerous material in it.”[172]

Profit not Protection: Ministry Interventions Unduly Limited

Under the Lebanese Harbors and Ports Regulations, Harbor Masters have a duty to monitor dangerous goods on ships and in docks and to take the measures necessary to preserve public safety.[173]

Nearly all of the actions taken by ministry officials appear to have been limited to trying to get a judicial decision to sell or re-export the ammonium nitrate and appear to have excluded measures they could have unilaterally taken to safely store or secure the material. Even the attempts to sell or re-export the cargo were badly managed, resulting in unnecessary delays and the ongoing presence of the hazardous material in Beirut’s port.

An internal Port Authority memo obtained by Human Rights Watch from January 2015 reflects that port officials could prepare lists of abandoned goods for consideration of removal and destruction by customs, including goods abandoned in port warehouses for longer than six months.[174] Human Rights Watch has uncovered no evidence, however, that this was done for the ammonium nitrate in hangar 12.