Introduction

Mental health service provision can—and should—respect the human rights of individuals seeking or receiving care. The necessary components of mental health services that respect human rights include informed consent, as well as the availability, accessibility, acceptability, and quality of mental health services. For more than a decade, Human Rights Watch, a global human rights organization, has pushed for a rights-based approach to services and supports for people with a range of disabilities in different settings around the world.[1]

According to the World Health Organization, in 2019, an estimated one in eight people globally—970 million—was living with a mental health condition, and yet, on average only 2 per cent of health budgets were dedicated to mental health.[2] Human Rights Watch research in more than 60 countries has found that mental health services frequently fail to comply with international human rights standards due to stigma related to mental health, the use of coercion, and power imbalances between the service provider and the person seeking or receiving support.[3] In many jurisdictions, inadequate legal and policy protections reinforce discrimination and abusive treatment of people with mental health conditions. The situation is particularly dire for individuals experiencing mental health crises, including in circumstances related to substance use, suicidal thoughts, trauma, housing insecurity, and poverty. Instead of receiving rights-respecting community-based services for their mental health needs, many people face punitive measures by law enforcement and other approaches that may not be suitable, such as in many cases, “wellness checks” by the police.[4] Such crisis responses expose individuals to the risk of police violence, criminalization, involuntary hospitalization, forced treatment, and displacement of unhoused individuals, and this risk is higher for Indigenous and racialized groups.[5]

As part of its growing efforts to promote solutions-oriented approaches, Human Rights Watch is documenting a series on good practices that may serve as useful models for governments and service providers to comply with the principles in the UN’s Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. As the first part of this series, Human Rights Watch documented the innovative approach of TANDEMplus, a mobile team in Brussels providing mental health services to people with psychosocial disabilities in their homes or a place of their choice, where they work hand-in-hand to find solutions and help the person regain control over their everyday life.[6]

One Canadian initiative, Gerstein Crisis Centre, stood out as a case study for mental health crisis support rooted in community and human rights. For more than 30 years, this community-based service provider has offered communities in Toronto safe, humane, equity-based crisis services. Gerstein Crisis Centre provides free and confidential 24/7 tailored support services to individuals experiencing a mental health and/or substance use crisis, including thoughts of suicide, all of which may be exacerbated by or emanate from trauma, housing insecurity, and poverty, among other things.

In 2021, Human Rights Watch and Gerstein Crisis Centre collaborated to present a snapshot of what a rights-based support service may look like, in contrast to the prevailing forms of mental health crisis responses that predominantly focus on police and/or forced hospitalization.[7] This case study provides a more detailed description of the Centre’s approaches and unpacks lessons learned and good practices emerging from decades of rights-respecting community-based mental health support. These good practices stem from the Centre’s experiences in Canada and are presented as a case study for service providers to consider given each unique context, rather than as a prescriptive guide. Every country and community has different needs that may require a different approach.

Section I outlines how disability justice and human rights frameworks should inform mental health services. It discusses the importance of rights-based mental health support, built on concepts such as recovery and agency. Section II provides insights into Canada’s mental health care system and the emergence of the Gerstein Crisis Centre more than 30 years ago, against the backdrop of Canada’s wider deinstitutionalization processes. Section III shares key pillars that shape the Centre, formulating the core lessons learned and good practices from the Canadian context. It stresses the importance of centering support around lived experiences and, as such, describes (1) how the Centre addresses power dynamics, including when working with or co-located alongside other actors, and (2) the core services the Centre provides. All sections highlight lessons learned and good practices for service providers to consider in order to promote crisis responses that are community-based and rights-respecting. Each section concludes with the lived experiences of Kaola, a woman who received support at Gerstein Crisis Centre and has continued to work with the organization as a peer to support others experiencing mental health crises.

Human Rights Watch is currently expanding its research on disability rights and mental health service provision, and the issues and good practices discussed here will inform its global research and advocacy on this subject, taking into account the unique specificities of culture, society, and politics.

Human Rights Watch and Gerstein Crisis Centre hope this document inspires action among and across mental health service providers, service users, policymakers, and human rights and mental health advocates on providing community-based and rights-respecting support to people experiencing mental health crises. This document provides examples of how this is being done in Canada, and we invite you to consider their applicability to your current and future work.

I. A Rights-Centered, Holistic Approach

Recent trends in standards and policies on mental health services, such as the Quality Rights guidance developed by the World Health Organization,[8] recommend placing people in mental health crises at the center of decision-making, prioritizing their choices.[9] This person-centered approach highlights agency, choice, and informed consent as the bedrock for the right to health and other human rights.

A human rights-based approach to mental health support also centers on a holistic response to the person’s needs—one that addresses the combined impact of social, physical, emotional, and environmental factors, including discrimination, structural racism, and other forms of exclusion and repression. Such a system should account for the person’s housing, food, and employment situation, among other needs. This also involves crisis responses that go beyond immediate de-escalation and stabilization, to enable people to recover their sense of belonging, inclusion, and connection with others.[10]

Such approaches conform to international human rights law, which has moved away from considering people with psychosocial disabilities as objects of care and instead engaging with them as rightsholders.[11] A one-size-fits-all response is not the solution but, at a minimum, recovery should focus on respect for the person’s own experiences, wishes, coping mechanisms, and choices, including the possibility of not receiving support.[12] Recovery is not about curing people or making them function in a specific way prescribed by society; instead, it should foster a sense of wellbeing that focuses on finding meaning in one’s life and an individual defining for themselves what is desired and hoped for to reduce the harmful effects of their pain and symptoms as much as possible.[13]

Flaws of the Current Approach

There is increasing consensus that people with mental health conditions are crucial contributors to the delivery and transformation of mental health services because they possess relevant knowledge and lived experience. Historically, however, services in many parts of the world rarely center on the person in crisis, meaning they often fail to prioritize the needs, perspectives, expertise, and experiences of individuals seeking mental health support.[14]

Many mental health services continue to have an overreliance on a “medical model,” which often decenters a person’s agency, over-pathologizes the individual, and reduces support to the urgency-driven provision of medication. Many times, the medical model does not focus enough on recovery-oriented approaches that more fully embrace human rights and fails to consider social determinants contributing to mental health crises.[15]

People with mental health conditions (or psychosocial disabilities) around the world often face stigma and prejudice.[16] False perceptions—such as the commonly held belief that people with mental health conditions are incapable of deciding what is best for themselves—pose major barriers to the enjoyment of their human rights. For centuries, professional knowledge regarding the diagnosis and treatment of mental health conditions has been valued over the knowledge and insight of people who live with those conditions.[17] Even today, treatment of mental health conditions can be coercive; for example, forced medication, forced hospitalization, removal from the community, and physical or chemical restraints continue to be used in many countries.[18] Such involuntary treatments can cause or worsen trauma.[19]

Despite significant evidence of its harms, coercion is often justified by classifying the person as a danger to themselves or others.[20] This classification is often vague and open to arbitrary interpretation and application by police officers. Coercion is also often framed as a “last resort” even though it can be—and has been—used as a first or emergency response.[21]

In Canada, as in many countries, police are typically the first responders to mental health crises.[22] When someone is experiencing distress, their emotional state may deteriorate when confronted by police due to power imbalances, fear of violence, and fear of being apprehended. This reaction can be particularly acute for Black, Indigenous, and racialized people who experience higher rates of police violence.[23] In Canada, such incidents too often happen when a concerned person calls the emergency services number (911) seeking help for someone experiencing a mental health crisis.[24] In 2021, four people in Canada were killed during police responses in the course of “wellness checks.”[25] Two-Spirit, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer+ (2SLGBTQ+) communities have also been historically mistreated by police in Canada, putting them at increased risk when seeking help during a mental health crisis.[26] Any use of force that discriminates against people with disabilities, Indigenous people, racialized groups, and 2SLGBTQ+ communities violates various international treaties and standards.[27]

Governments and other funders have not sufficiently invested in community mental health services. Consequently, the capacity of existing community- and rights-based services is still stretched, often resulting in a mental health crisis response that prioritizes reliance on law enforcement and hospitals.[28]

Barriers to Rights-Respecting Mental Health Crisis Support Services

The establishment of a rights-respecting community-based crisis intervention service can be daunting, especially in environments where medical and psychiatric responses to mental health crises—which can include involuntary detention and treatment, violence, and coercion—continue to dominate and where the government or local authorities tacitly accept human rights violations and abuses. While police involvement in mental health crises has been challenged by communities across North America following incidents of police violence and deaths of individuals in crisis, police remain the first responders to mental health crises in many places. Every person, including anyone who may be struggling with their mental health, deserves to have their rights respected.

Community-based crisis services can improve immediate responses and access to follow-up support. However, long waitlists for housing, lack of culturally relevant counseling and mental health services, as well as insufficient financial assistance, often leave people isolated and unable to access health and social resources in a timely way, which can contribute to escalating and repeated crises.

An overly narrow focus on crisis response without adequate investments in a broader range of community resources to address social determinants of health (such as housing, employment, and income support, and equitable access to rights-based treatment and services) also undermines the government’s obligation to uphold the right to the highest attainable standard of health. In particular, such a narrow focus can undermine the perceived effectiveness of a broader range of community resources, while continuing to obscure under-investment in health services and the social determinants of health.[29]

Mental health support should be available through a low-barrier health support system rather than law enforcement. In particular, the goal of such a low-barrier system is to provide easy, timely, and equitable access to quality health services and support for everyone within the community—with minimal requirements for connection and entry. Marginalized communities, such as 2SLGBTQ+, Black, Indigenous, and racialized people have specific generational and lifelong experiences of discrimination and exclusion in health and social systems that too often resulted in over-policing and over-incarceration. Services should reflect the experiences of the communities served, including those who are often subject to coercive medically-focused responses, racism and other human rights violations such as inequitable access to housing, employment, and education (commonly understood as the social determinants of mental health).

Kaola’s Lived Experience: “I have lived my entire life in absolute fear”Kaola Baird, a resident of Toronto, received support at Gerstein Crisis Centre and continues to work as a peer to support others experiencing mental health crises.[30] I don't really see my story as being something so fantastical because I've met a lot of people who have really lived with a lot more challenges than I do. … But I have lived my entire life in absolute fear. I experienced a loss when I was very young—my mother. She was quite ill after she had me and proceeded to just go downhill. She died a couple of days after my second birthday, and apparently, we were just starting to bond. She had a really horrible, painful death. And I did not even really process her death until I was 18. My aunt raised me well; she's my mum. And I knew the story of my mother's death, but it didn't really register. It was just—it was a story. But I had been struggling with depression and it got progressively worse. By the time I turned 16, I was self-medicating, as in reaching into the medicine cabinet, just wanting to go to sleep and hoping that I wouldn't wake up. And I was never sure why I just always felt different and alone. Like I didn't really belong anywhere. And I was not connected to anyone. I realize now that I was lucky enough, when I was at my lowest point, to have a place to reach out to get help and the support I needed. Because even though I feel suicidal, I'm also really, really scared. |

II. The Emergence of Community-Based Mental Health Care in Canada

From the mid-1900s to the early 2000s, psychiatric hospitals gradually closed across Canada. This deinstitutionalization was fueled, among other factors, by provincial governments’ belief that community care would cost less and by the growing awareness of institutionalization’s long-term harms.[31] By 1981, the Province of Ontario saw a 75 percent decrease in bed capacity at psychiatric facilities, and similar changes took place across the country. Nova Scotia Hospital in Dartmouth, for example, reduced its beds from more than 1,000 in the 1960s to fewer than 200 by 2003.[32] The overall reduction of space discharged people from psychiatric hospitals into the community, rendering them reliant on community mental health services that were poorly funded, if they existed at all; in many jurisdictions, they were altogether absent.[33]

Following this process of deinstitutionalization, people in some communities were left unhoused and without access to basic services. In response, in 1983, the mayor of Toronto established a task force to investigate the situation for people who had been discharged from psychiatric hospitals and who were living in the city.[34] The task force’s report and recommendations laid the groundwork for a coordinated community response to address the key issues facing people who were living with mental health conditions, which would bring together the municipal, provincial, and federal governments. One key recommendation was the formation of an independent, community-based, standalone crisis center.[35] This made way for an effort to shift away from the medical model to a community-based approach that puts people with lived experience at its heart, like that of Gerstein Crisis Centre.

Establishment of Gerstein Crisis Centre

In 1989, the chair of the Toronto task force, Dr. Reva Gerstein, in collaboration with community members, including people with lived experience of mental health systems, founded Gerstein Crisis Centre. With funding from Ontario’s Ministry of Health, the Centre started by offering telephone and mobile services. In 1990, the Centre established 10 crisis beds and offered three-day crisis stays.[36]

At that time, the main source of support for people with mental health conditions in the city was a strict medical model centered around hospitals and rife with coercive practices.[37] Many people with mental health conditions, as well as progressive mental health professionals, advocated for a rights-respecting and recovery-based crisis response—one that understood that crises were not inevitable consequences of mental health conditions. They promoted an approach that recognized that crises often resulted from the combined impact of social, physical, emotional, and environmental factors, including a lack of access to essential services and supports, poverty, unstable housing, coexisting substance use, other health conditions, traumatic experience, racism, sexism, and gender discrimination.

More than 30 years later, Gerstein Crisis Centre continues to provide an alternative to hospitals and police stations to support individuals in a mental health crisis. The Centre uses a philosophy of care that centers the lived experiences and safeguards the autonomy of people experiencing mental health distress, enabling them to choose the support they consider is best and connecting them to resources, as needed and desired, to assist in their recovery. To do this well, Gerstein Crisis Centre recognizes the importance of building and strengthening pathways and partnerships that improve access to health and social services for individuals in crisis. Service provision, and its related approaches, should evolve over time to meet current needs and address gaps across systems.

The impact of Gerstein Crisis Centre illustrates the importance of scaling up and expanding such programs, including co-designing such programs in collaboration with local community members and people with lived experience, particularly as law enforcement and involuntary treatment continue to be the primary responses to mental health crises in many jurisdictions around the world, including in Canada.

Kaola’s Lived Experience: “There is still a person underneath”I was in the process of rebuilding my life and doing a fairly good job at it, but I’d been battling chronic depression ever since I can remember. I was forced to realize what had been haunting me, holding me back. It just triggered a tsunami, and I was very suicidal. It's not the first time in my life that I experienced that, but it was the first time in many years. And my world was collapsing. I was about to lose everything—I had been working and going to school, but I was in the process of losing my apartment. The things that I needed to do or had wanted to do, I couldn't do because of this desperate fear of—I'm not sure what. But everything came to a head. And I finally did call Gerstein, and so they came out to see me in the community. I was desperate, scared. I knew my life was about to change immensely and I felt I was very alone. I'm not one to talk to people about what's going on in my private life. You know, I have my close friends and they know my general situation, but I never want to be a burden on people. My first stay at the center allowed me to have a good night's sleep. I was still able to work at the time and I could come back, come home, and relax. I think sometimes being out of your regular space, you're forced to just let go. The people were warm and amazing and supportive. And the physical environment for me—that was important. I remember stepping into the house and there was soft jazz in the background and lots of artwork and the lighting … It was very inviting. It was very soothing. And I started to let go and I guess have better perspective on things. It didn't make the immediate crisis go away, but then you can see clearly, so you can make decisions, you can make better decisions. And that was an important first step. When you normalize what a person is feeling, when you can remove that sense of panic and then move to step one and just focus on that step one, and then you deal with step two after—it felt the way I imagined turning to your family for help would feel. … You also have access to resources and it's not crossing any boundaries. So, you still have your independence and your sense of privacy, but there's a warmth and a trust and a normalization of what you're going through. You don't feel like a client or a number or that you're being processed. I shudder to think … Had the police been called for me, I would assume that I would have been taken to a hospital. This is where I feel rather fortunate because I have had experience with self-admittance to hospitals, but I can imagine being scared and being in a different frame of mind that can send you deeper into whatever break you're having. And that wall of fears is a different, difficult one to climb over. So, I would shudder to think what would happen if I were in those shoes. I think when you're going through a crisis, depending on the person and the situation, I think sometimes you lose a sense of who you are. Because everything becomes about this thing that's happening. And as much as you can maybe have a window and see that there are those other things happening in life. And there's more to it than just this cloud. That's going to be different for each and every person, but I think there's always a window somewhere. And I think there's a lot to be said for not wanting to be seen as your crisis because there's still a person underneath. I'm not my illness. I'm not my diagnosis. I'm not whatever crisis I've lived through. |

III. How Can a Rights-Centered Approach Work?

This section provides a case study on lessons learned and good practices, based on Gerstein Crisis Centre’s rights-respecting and community-based approach in Canada. The aim is to assist communities and service providers who are considering how best to establish rights-based, people-centered services for individuals experiencing mental health crises, taking each community’s unique context into account.

Gerstein Crisis Centre provides 24/7 community-based mental health services geared toward diverting individuals aged 16 years and older in mental health crises away from unnecessary interactions with police and hospital emergency rooms. The crisis intervention services include:

- The telephone crisis line team is linked directly to the Centre (at 416 929 5200) and also accessible through a municipal helpline (211) that connects people to social services, programs and community supports;

- A crisis worker is co-located in the 911 Call Centre responding directly to mental health calls that have been diverted away from police dispatch;

- A mobile crisis team that follows up on calls in the community upon request, serving two high-needs neighborhoods;

- Crisis beds in private rooms in two large houses that provide a safe, homey, and supportive environment, staffed around the clock, designed for short-term stays of up to 30 days;

- Short-term follow-up support, including referrals to other beneficial health and social services; and

- Recovery programs, led by individuals with lived experience of mental health, substance use, and the criminal justice system.

The Centre employs about 100 people, the majority of whom have lived or living experience with mental health conditions or substance use. In the fiscal year 2022-2023, 56% of the Centre’s staff, as well as 40% of the Centre’s leadership team and 43% of the Board, had such lived experiences. The phone and mobile crisis workers are experienced intervention specialists, many of whom have lived experience and who reflect the diversity and voices of the communities served. Starting with the initial phone call to the crisis line, the individual in crisis guides what services they would like to receive and tells their story to a crisis worker, whose first step is to listen.

People who seek support from Gerstein Crisis Centre present various concerns that intersect with a mental health crisis. In the fiscal year 2022-2023, according to Centre intake data, 66 per cent of people who engaged with the Centre identified increasing concerns with mental health or substance use as among the reasons for seeking support; in addition, 60 per cent reported issues of isolation, 24 per cent relayed concerns regarding insecure housing, and 20 per cent reported suicidal thoughts. Others reported concerns regarding physical health (25 per cent), family or relationship issues (18 per cent), legal issues (6 per cent), physical or sexual abuse (5 per cent), and employment related issues (3 per cent). The variety of concerns identified by people seeking support at the Centre illustrates the critical importance of person-centered services embedded in a holistic approach that begins with a crisis worker listening.

There are four key components of Gerstein’s person-centered, holistic approach:

- Address power imbalances;

- Build trust;

- Listen to people with lived experience and include those voices in governance and leadership; and

- Engage partners across diverse sectors.

Gerstein Crisis Centre Today: What does success mean?Elaine Amsterdam has worked at Gerstein Crisis Centre since 1989 and was part of the first mobile crisis team. Though the organization has grown and evolved, its foundation and the meaning of success has remained consistently rooted in health and social justice:

|

Addressing Power Imbalances

Stigma, marginalization, poverty, and explicit or implicit bias predicated on race, disability, sex, gender identity or expression, language, and/or immigration status, among other things, can influence power dynamics, diagnoses, treatment, and endanger human dignity and even lives.

To reduce power imbalances between the service provider, the service recipient, and the systems and institutions that support them, Gerstein Crisis Centre proactively engages the individual in crisis in the spirit of collaborative interventions rather than coercive ones, and in a safe, unintrusive manner.

For example, the Centre’s Mobile Crisis Intervention Team wears regular clothes rather than uniforms or logoed apparel and uses vehicles with minimal if any markings. The aim of this practice is not only to minimize the experience of power differences that a uniform may promote but also to respect the dignity and privacy of the person in their community by not publicly advertising that the workers or the vehicles are associated with crisis intervention services. Crisis workers carry Gerstein Crisis Centre identification and service materials, as this low-key approach helps create a sense of safety for people they meet in the community. Mobile crisis intervention teams engage in conversation with the person in crisis to learn about the presenting crisis. They listen to the person to learn what is happening with them at the moment and then help identify the immediate needs or concerns, including physical needs and safety risks (e.g., current thoughts of suicide or self-harm).

WHO Guideline: Understanding Power RelationsWithin the mental health or social service context, people using the services depend on staff for their well-being and to receive services. They require the expertise of staff for their treatment and care over which they often have no control. This dependence on staff and lack of control can put them at particularly high risk of coercion and violent and/or abusive treatment.[38] A number of factors can influence and exacerbate the power dynamics in mental health and social services:

Given the potential power dynamics in a service, the behaviour of staff towards people using the service has a huge impact on their rights as well as on their well-being and recovery. Identifying and preventing violence, coercion and abuse can happen only when people acknowledge the unequal power dynamics in a service and change their behavior accordingly. A respectful and supportive contact decreases chances of escalation and reduces the risk of violence, abuse and coercion. All people deserve to be treated on an equal basis with others, with dignity and respect. |

Building Trust with Service Users

Trust is at the core of relationships and can lead to quicker de-escalation of crises. To foster trust, the Centre works together with the person in crisis to understand and find the best way forward for them as an individual. The team does this by listening intently to the person, inviting them to share their story from their perspective, acknowledging their feelings, identifying their strengths, providing support networks, and demonstrating a thorough understanding of their situation. The team also reassures the person that their immediate basic needs, such as food, drink, and shelter, will be met, which can greatly promote trust and indicate a genuine recognition of the whole person. As such, crisis intervention is understood as a collaborative process that begins with connecting and rapport building to better understand the individual’s experience and context before co-creating a crisis and safety plan.

Gerstein’s crisis response includes supporting people with complex needs, including suicidal thoughts, substance use, mental health conditions, trauma (including inter-generational trauma associated with discrimination), housing insecurity, and poverty. This requires staff to be nimble and flexible. Responses and service plans are specifically shaped to respect the communication and service needs of each individual and to meet them where they are comfortable engaging: within the context of their unique history, perspective, and quality of life and health goals. Simultaneously, the crisis team assesses the individual’s immediate safety, explores any concerns in this regard, and works with the individual to develop a safety and crisis plan to help mitigate the identified concerns. Sometimes building rapport and connection is immediate; often it builds over multiple interactions across time, where greater trust needs to be established. In some cases, the person prefers to be referred to other alternatives, and the crisis team facilitates this process as well.

A Typical Pathway to Support at Gerstein Crisis CentreThe telephone crisis line is typically how people access support services at Gerstein. An individual experiencing a crisis—or someone else concerned about an individual, such as a friend, family member, service provider, medical professional, doctor, police officer, or a stranger or—can call the crisis line and speak directly to a member of the crisis team. Regardless of the caller, any engagement requires the consent of the person experiencing a crisis. Most often, the crisis worker and the individual concerned address the crisis over the phone by creating and agreeing upon a crisis and safety plan. If more support is needed, and only if the caller consents, that same crisis worker will take a teammate with them to visit the caller in the community on a mobile crisis team visit. No medical professionals or police officers are involved in Mobile Team visits; only trained mental health crisis workers, many of whom have lived experience, respond, and the information they gather remains strictly confidential. Mobile crisis team visits happen anywhere it is safe to meet; for example, someone’s home, a coffee shop, or a park. The Mobile Team can offer the individual concerned a stay at the Centre, one-to-one conversation, crisis counselling, referrals to external resources and follow-up. |

Crisis responses seek to identify and reinforce the personal strengths of the individual in crisis to help them recover from the crisis and protect themselves against further occurrences. This entails inviting the individual to start determining their future based on their strengths; that is, what is “right” in their lives rather than what is “wrong.” This aims to build confidence and comfort, which is especially important in circumstances where there are many uncertainties about basic necessities and ways forward. In this way, the crisis worker helps the individual value themselves and collaborate on developing a crisis plan to address their needs.

Key Features of a Crisis Plan at Gerstein Crisis CentreGerstein Crisis Centre and the person in crisis collaboratively develop an individualized plan that typically includes:

|

Service is provided to anyone who calls Gerstein Centre and anyone who is part of the person’s immediate support network, such as a friend, neighbor, or family member. It is important to recognize that, in some circumstances, a person calling about someone they are worried about may also benefit from crisis intervention, support, resources, and referrals.

Gerstein Crisis Centre endeavors to be responsive to the culture, race, age, disability, sexual orientation, gender identity and expression, health literacy, and language needs of the people it serves. The Centre intentionally hires crisis responders who have lived experiences of mental health conditions and substance use, and who reflect the diversity of the communities they serve. Having a team with varied backgrounds and experiences allows people in crisis to see themselves reflected in crisis responders, creating greater opportunities for engagement and connection. It also brings a greater depth of experience and expertise to the Centre’s crisis teams.

Gerstein Crisis Centre values equity and thus its service providers are required to participate in continuous learning and specific trainings, including on anti-racism and anti-oppressive practices. The Centre also encourages its service providers to critically analyze approaches, teachings, research findings, and understandings in the field of crisis intervention that were developed inside and outside Canada. The Centre can refer the individual in crisis to culturally appropriate services, if desired by the individual. In addition, Gerstein Crisis Centre has 24/7 access to interpretation services in more than 180 languages.

Centering Lived Experience in Leadership

The voices of people with lived experience of mental health conditions and substance use should be at the core of rights-based services and support at all levels.

Gerstein Crisis Centre engages people with lived experience in every aspect of its work, including as members of the crisis intervention team and leaders in the organization. The Centre’s governance structure and by-laws require that at least 30 per cent of the Board of Directors are people with lived and living experiences of mental health conditions or substance use.

Key Elements of Services Sensitive to People with Diverse Backgrounds

|

Engaging with Partners Across Sectors

A key aspect of improving access to health, social, and other support services is engaging in collaborations with individual, community, and governmental partners within and across sectors.

Gerstein Crisis Centre has many partnerships that leverage expertise to better serve client populations, including supports and services for older people, transitional-age youth, Black and Indigenous people, people with disabilities, 2SLGBTQ+ communities, and survivors of trauma. Services are also available to address substance use and harm reduction, food insecurity, and income support, as well as issues related to the justice system, housing insecurity, shelter assistance, and primary care. To that end, the Centre has created pathways and connections to support services that address some of the underlying issues that can contribute to a mental health crisis. This work is ongoing, and new pathways and partnerships are always being formed to address emerging gaps in services.

Avoid Unnecessary Emergency Medical and Police Interactions

Mental health needs are best met with a consent-based health response and quality services that are timely and equitably accessible. Free and informed consent is a human right. Key elements of free and informed consent include prioritizing the autonomy of the individual in crisis in determining next steps. The individual’s wishes are paramount: if they do not want to engage, they can be invited to seek services again if they change their mind. There should be no pressure on the individual to change their mind.

WHO Guideline: Informed Consent and Person-led Treatment and Recovery PlansIt is important to be aware of the risk of undue influence due to the power imbalance in relationships that exists within mental health and social services. There is sometimes a fine line between supporting people in making their decision and unduly influencing them.[39] Informed consent means:

The right to informed consent also includes the right to refuse treatment. This means that if a person, after being offered information about treatment options, decides they do not want any kind of treatment, this is their right and must be respected. |

In the vast majority of situations, the Centre responds first with trained mental health crisis workers—without engaging emergency medical services or the police—to maximize the participation and choice of the individual in formulating their own crisis plan. Information gathered in the course of providing crisis services remains strictly confidential. This approach addresses crisis situations without the risks of coercion or criminalization. It also ensures that the rights and decisions of service users remain paramount.

In its advocacy to shift mental health crisis responses toward rights-based community support, Gerstein crisis workers participate in various initiatives to divert people away from a criminal justice response. These include weekly “Situation Tables,” co-organized by the City of Toronto, Toronto Police Service and United Way Toronto, where community-based service providers come together to divert people in crisis (that is, people who are at elevated risk of criminality or vulnerable to criminalization) away from law enforcement and refer them to community-based supports through “a targeted, wrap around approach.”[40] These Situation Tables bring together representatives from Gerstein Crisis Centre, as well as representatives of community agencies providing housing support, case management, income, and other beneficial service supports.

Gerstein Crisis Centre also offers short-term residential crisis beds and support in Toronto for individuals who are referred by police or other criminal justice sources. All individuals referred have current involvement with the criminal justice system, are unhoused, and are experiencing mental health conditions and/or substance use. All stays in the crisis beds are consent-based, and Gerstein Crisis Centre does not report to the police any infractions with bail orders. Instead, the Centre works with people on setting goals that are meaningful to them and supports them in pursuing those goals.

In 2021, the Centre expanded its services, piloting a project that places crisis workers at 911 communication centers to provide immediate crisis intervention to callers rather than sending a police response. Crisis workers sit alongside 911 operators to receive calls diverted to their confidential line, and they provide immediate crisis response and intervention, follow-up, and connection to beneficial services as much as possible.

In 2022, Gerstein Crisis Centre expanded again to launch the Toronto Community Crisis Service Team, a non-police response that can be accessed by calling 911 or 211 (a municipal helpline that connects people to social services, programs and community supports). This team of crisis intervention workers is co-located in the call centre where 911 calls are received prior to dispatch to fire, police, or ambulance. The goal is to provide immediate crisis intervention and to help avoid unnecessary interactions with police. Instead of the 911 call taker sending a police officer, the community crisis workers engage with individuals experiencing mental health crises, providing crisis and suicide interventions, de-escalation, connection to health and social services, harm reduction supplies, and other resources, including things like warm coats, water, food, and up to 90 days of follow-up. Once a caller is diverted to a Gerstein crisis worker, the call is forwarded to an independent private Gerstein phone line that is not monitored by police. All services are voluntary and consent-based and divert individuals away from unnecessary police and hospital interactions. In fiscal year 2022-23, almost 2,000 calls were actioned by the Gerstein co-located crisis team, all with the goal of diverting the caller to a mental health, trauma-informed, hard-reduction response and avoiding a police response.

The Centre’s non-medical low-barrier approach, as well as its multiple access points, allow individuals to seek tailored support in the community when and where they need it. Many people who use the Centre’s services value having the choice to get crisis support without going to the hospital or involving law enforcement. They feel they can reach out as soon as they are struggling, not just when it becomes an emergency. Reaching out earlier allows the Centre to provide support, develop strategies, and facilitate community linkages to the resources needed to help prevent crises from escalating or taking place at all. Gerstein Crisis Centre also receives referrals from emergency rooms after the person in crisis has been seen if the hospital believes further crisis support in the community would be beneficial.

How Can a Service Provider Uphold Its Values While Working with Other Actors?Different actors involved in mental health crisis response, such as the police, emergency medical services, hospitals and abstinence-based services, may use different approaches. In such interactions, it is important for community-based and rights-respecting service providers to uphold fundamental values and maintain integrity while improving coordination and collaboration to better serve individuals and the community. The following are some questions to consider asking when collaborating with actors that have a different focus or approach to mental health crisis response:

|

What Are Some Core Elements of a Rights-Based Approach to Crisis Service?

Services such as a 24/7 telephone crisis line, mobile crisis intervention teams, and a house with crisis beds can reflect a rights-centered, non-carceral, holistic approach. Gerstein Crisis Centre’s work offers insights into how this can be done in compliance with international human rights standards.

Involvement with the Centre is completely voluntary and based on free and informed consent. Clients retain autonomy and the ability to continue, end, or reengage with the Centre at any time without fear of recrimination. Other follow-up services and referrals to other community supports can be provided at any juncture.

In the fiscal year 2022-2023, the Centre responded to 38,892 crisis calls, provided 10,828 mobile visits in the community, and hosted 805 house stays in the Centre’s short-term residential accommodation.[41]

Telephone Crisis Line

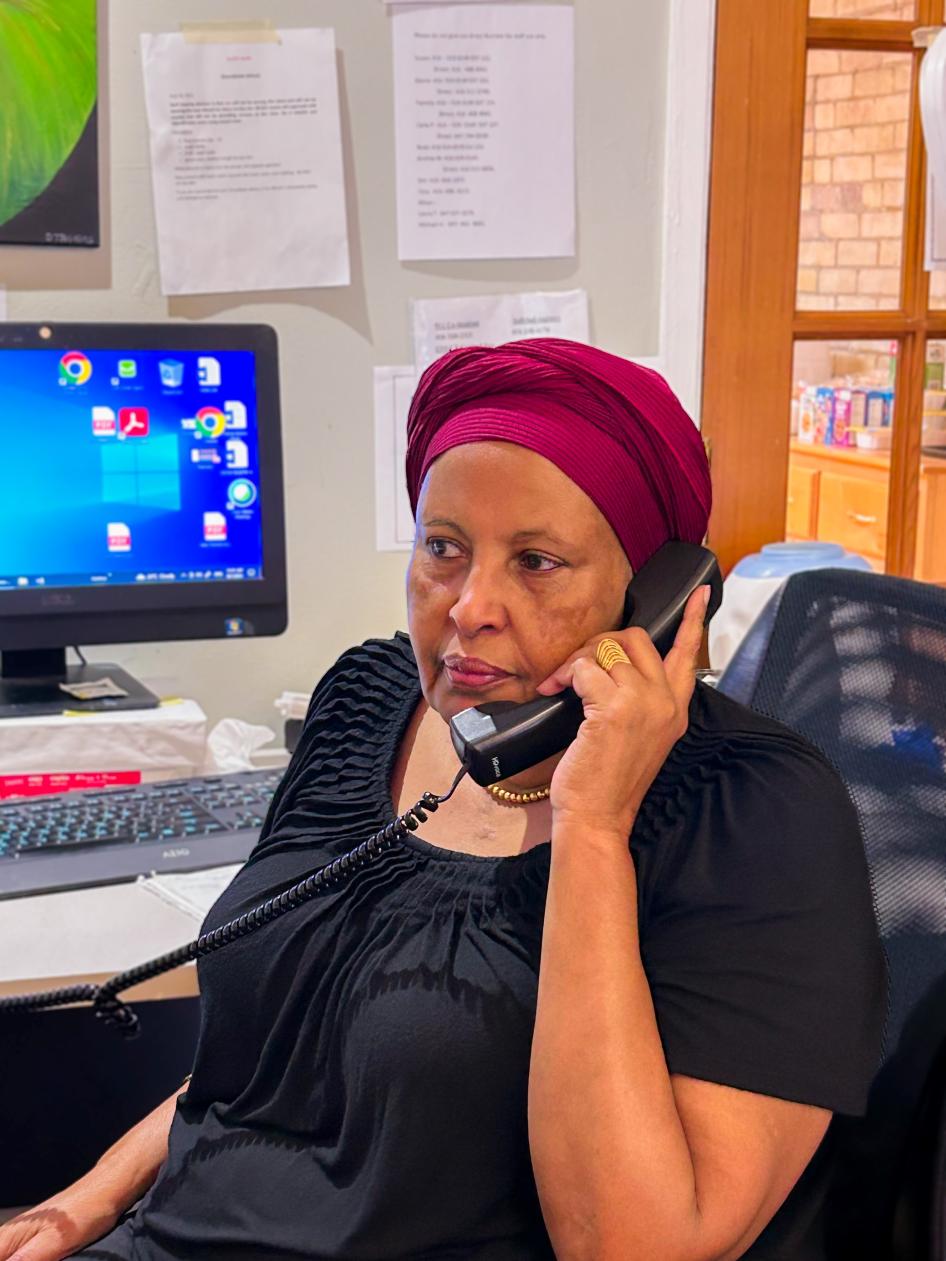

Individuals experiencing a crisis can call the Centre’s 24/7 telephone crisis line and receive support from skilled and experienced crisis workers, including people with lived experience. Service is provided immediately over the phone, in English, French, and more than 180 other languages using interpretation services.

When someone calls Gerstein Crisis Centre’s telephone line, conversations usually start on a first-name-only basis for both the service user and crisis worker. The Centre respects the choice of anonymity, which may facilitate greater openness and freedom for some callers. First, the crisis worker endeavors to establish connection and build rapport quickly. The crisis worker helps the person share their story and current situation. The crisis worker takes an active, supportive stance, integrated with empathy, active listening, and understanding in order to help define the caller’s concerns, acknowledge their feelings, ensure safety and support for them, clarify choices and alternatives, and collaborate to make a crisis plan that suits the caller.

WHO Guideline: Key Strategies to Avoid and Defuse Conflictual SituationsMany people using mental health services have experienced trauma in their lives. When violence, coercion and abuses occur in mental health services, not only do the service fail to help people but they compound the original difficulties, by retraumatizing people using the service.[42] When working with a person in distress, a good start may be to ask first what could bring relief (e.g. if there is a preferred person who could be contacted, or if there is a specific need). Since most tension starts from discomfort and powerlessness, listening carefully and reducing powerlessness are key. In addition, responding early reduces the chances that the situation escalates into a conflict. An appropriate and effective response to a tense situation involves:

When dealing with tense situations, it may be necessary to think about the safety of all the persons around (e.g. asking people whose presence is not necessary to leave the room or to stay at a safe distance). |

Mobile Crisis Intervention Team

After a call on the Centre’s telephone crisis line, Mobile Crisis Intervention Teams conduct a follow-up in the community upon their caller’s request. This decision is usually made within 10 to 30 minutes over the telephone. Depending on distance, urgency and availability, the team will estimate 40 minutes to 4 hours for arrival. Additional telephone support can be provided in the meantime.

The team focuses on the person in crisis and their expressed immediate needs, taking a collaborative approach that prioritizes informed consent. Situations are addressed in a low-stigma, non-intrusive, and non-threatening manner that uses engagement, listening, and collaborative problem-solving to de-escalate the situation and achieve greater safety for the person and their community. While the focus of engagement is assisting someone to cope more effectively with their immediate stresses, the mobile crisis intervention team understands that the individual exists within a wider context beyond their crisis.

De-escalation and Suicide InterventionDarna Savariau-Daley has been a crisis worker at Gerstein Centre for over 30 years, handling the crisis helpline and working as a member of the mobile crisis intervention team. A large portion of the calls the Centre receives come from individuals with suicidal thoughts. Darna described the Centre’s approach to de-escalation and suicide interventions: “We do a lot of listening: we hold your hand and help you through whatever you’re going through. What’s the best course of action we can take with you? Part of my job is to give people as much information as possible, give them the choices, and then together we make a decision. Sometimes, it’s a matter of just listening with compassion and saying, ‘hey, it’s okay, we all go through bad times; let’s talk about it and see where we can go with it.’ It’s very low-key and informal.” Where a caller expresses suicidal thoughts, crisis workers begin with assessing safety to find out whether the person has already hurt themselves, and whether they have a plan and the means to harm themselves or others. “It’s not a one size-fits-all,” according to Darna. “We talk about how they are feeling and what’s behind those thoughts. We focus on their strength base: ‘What has kept you going?’” The Centre only calls 911 in cases involving immediate life-endangering situations. If, for example, a person in crisis has already swallowed a bottle of pills, then the situation turns into a medical emergency and medical intervention is needed. In almost all such cases, the crisis worker informs the person in crisis that paramedics are on the way. The crisis worker helps determine with the person in crisis if there are choices that can be addressed and advocated for with emergency responders. The crisis worker continues to support the person before paramedics arrive and afterwards, once the person has been medically cleared. The only very rare exception to letting the person in crisis know that paramedics are on the way, is if there is indication by the person that disclosing the call to 911 would further endanger their life and/or that of someone else. Every effort is made to preserve a person’s life in a manner that supports their dignity and choice. All crisis workers are trained in suicide intervention and will ensure that each call about suicide begins with exploring why someone feels the way they do that day and ends with a safety plan in which both the caller and crisis worker feel confident. |

Houses with Crisis Beds

Gerstein Crisis Centre operates two houses with crisis beds, providing a safe, supportive environment that is staffed around the clock. One-on-one crisis counselling, referrals, and support are provided. The houses also serve as headquarters for both the telephone crisis line and the Mobile Crisis Intervention Team. In the houses, people can access what they want to take care of their own needs as much as possible. The kitchen is always open, and residents can help themselves to food in the fridge when they would like a snack or a meal. While staff and/or volunteers prepare dinner for the whole house, people are encouraged to make their breakfast and lunch; assistance is available if requested.

WHO Guideline: Recovery Focus on StrengthsToo frequently services focus on people’s problems and deficits. An essential part of recovery is for people to identify and build on their assets and strengths. This does not mean denying the pain and distress that a person may experience. These feelings should be acknowledged, and the person should be supported to explore them and find ways to overcome them, using their strengths and assets.[43] |

|

|

Deficit-based approach |

Strength-based approach |

|

Starts with deficiencies and responds to problems. |

Starts with assets and identifies opportunities and strengths. |

|

Provides support that is limited by the service’s specific mandate or policy rather than focusing on the needs of the individual. |

Sees people as experts in their own recovery and acknowledges that people are capable of making decisions. |

|

Requires practitioners or other supporters to move from “fixing people” to supporting recovery. |

|

|

Treats people as passive recipients of care. |

Emphasizes collaboration and co-production between the person concerned and practitioners and other supporters in the recovery process and journey. |

|

Sees problems or deficits as existing within the person themselves and tries to “fix” or “stabilize” the person. |

Views and treats the wider community as assets. |

|

Empowers people to better take control of their lives and supports them to develop their potential, with an understanding that they themselves hold the answers and solutions. |

|

Spaces within the houses are designed to provide a home-like, healing environment that is respectful and dignified. Space is a major concern for many service users as they often live in congregate environments, such as shelters or supportive housing, where they lack the personal space or privacy they need during a crisis. All crisis beds are in individual private rooms so people can have their own space and the ability to lock their doors to strengthen their feelings of safety and security.

The Centre also pays attention to furnishings and wall colors, intentionally selecting items that appear “non-institutional” and striving to financially support people with lived experience in the process. Social enterprises that employ people with lived experience of mental health crises made a lot of the furniture, people with lived experiences gifted or sold all the art on the walls, and social enterprises provide all cleaning and catering.

F.R.E.S.H. (Finding Recovery through Exercise Skills and Hope)F.R.E.S.H. is a Gerstein Crisis Centre initiative that uses a peer-led model to help people get active, strengthen their community and social connections, develop new skills and knowledge, and have fun. Group activities include yoga, gym groups, bocce ball, boxing, ball hockey, trail hikes, walking groups, and more. For participants who would like to take their fitness to a higher level, individualized one-to-one sessions with a F.R.E.S.H. worker or fitness partner are available. All F.R.E.S.H workers have lived experience of mental health conditions and/or substance use and have navigated many of the issues participants are facing. They all have a passion for physical activity, education, and social/community involvement. |

Kaola’s Lived Experience: “It's a rejuvenation, and that has a ripple effect”Some of the best advice and information I received were from other peers—experiences that they had, things that they did. This definitely allows me to share with other people who are going through things that I went through. I think when you've been through journeys in life, whether it was mental health connected or not, I think when you're able to come out the other side, you really do appreciate things. Whereas before I didn't really feel a purpose in life … it's the little things that I do now that that give me purpose. When I meet people now who live with very, very challenging diagnoses, I don't necessarily always know their story. I may never know their story. And that's a good thing because when you meet that person, you just start there, and you don't assume anything of them. And then they will let you in. And they know that their problems haven't been resolved fully. But it's a rejuvenation, and that has a ripple effect. And I've seen it. … I've lived it. Whatever the person's medical health condition is, whatever stage of recovery they're at, that's part of their story. It's not who they are. And I think it's good to remind them and to remind ourselves that we're more than what goes wrong in our life. My gratitude to those that helped me at Gerstein as the years go by—I can look back and think about those times and actually be so thankful and grateful for the opportunities that I've had because of it. Those are things that helped me appreciate what other people are going through. I learn from the people that I work with, but then I can also listen, and we can exchange stories about how an experience feels or what it means. And by going through it myself, I think it just gives you that deeper understanding. … I have a lot of empathy. … I try to give back what I received and still do receive. You just go full circle, but for me, I always think the circle gets larger. Because then you get more tools in your toolbox and hopefully you learn, and you grow. |

IV. Key Recommended Practices for Communities and Service Providers

The following are key recommendations for communities and service providers developing and delivering mental health crisis support services:

Power Dynamics

- Center human dignity and autonomy, a collaborative approach to service provision, and the perspectives of people with lived experience, particularly the individual in crisis.

- Intentionally strive to mitigate power imbalances between service users and service providers.

- Prioritize the autonomy and expressed needs and desires of individuals in crisis to build trust, and tailor strategies to a particular individual in crisis.

Collaborations and Partnerships

- Establish and build strong relationships with individual, community, and governmental actors across diverse sectors while upholding a rights-based approach to crisis support.

- Closely consult and collaborate with individuals and organizations led by people with lived experience.

- Collaborate and partner across sectors to create multiple, intentional access to needed health and social services that direct people to community crisis responses.

- Engage in advocacy on a broader range of community resources to address social determinants of health, including housing, employment, and income support, and equitable access to treatment and services.

- Establish low-barrier, client-driven early access to mental health and crisis support.

- Collaborate with hospitals to create pathways to community-based support.

Crisis Service Provision

- Offer crisis services 24/7 to ensure services are always available when needed.

- Include different methods of immediate crisis responses, such as phone and in-person services.

- Make immediate crisis responses available in the language the person in crisis prefers.

- Be able and willing to meet the individual in crisis where that person is comfortable.

- Prioritize the autonomy of the individual in crisis in determining the next steps, such as whether they want to stay at the Centre. If they do not want to engage, invite them to seek services again if they change their mind, but do not pressure them into doing so.

- Houses with crisis beds should feel home-like and “non-institutional.”

Governance

- Establish an independent organization with a governance structure driven by lived experiences, firmly rooted in the mission, vision, and values of the organization.

- Meaningfully include people with lived experience at all levels of the organization, from service provision to leadership roles.

- Ensure that a critical mass of people with lived experiences serve on the board and in other decision-making roles.

- Seek adequate, appropriate, sustainable levels of financial support to ensure stability of operations.

- Urge government entities to support community-based service providers with adequate funding, preferably core funding.

Evaluations and Accountability

- Engage external evaluators to maximize unbiased gathering and analysis of data.

- Involve people with lived experience in leading and facilitating the evaluation to create environments where service participants are comfortable sharing honest information about their experiences.

- Ensure evaluations identify service gaps and make recommendations on improving service provision to better respond to the needs of the communities served.

- Develop a strong accountability framework that combines appropriate and recommended standards of practice with a commitment to inclusivity and social justice practice.

- Solicit the experiences and observations of service users and implement their recommendations for change.

Afterword

Mental health is receiving unprecedented global political attention, yet in most regions, there continues to be little to no recognition of the social context in which mental distress occurs or what the activism of people with lived experience can offer to promote humane and rights-based approaches. Indeed, too often mental health recovery models and their basic tenets of choice and autonomy are constrained by biomedicalism, over-policing, and deeply engrained stigmatizing and discriminatory attitudes toward people experiencing mental distress.[44] These enforcement models risk overriding people’s rights and perpetuating responses that may be discriminatory, coercive, violent, and traumatic.

Despite these challenges, service users and people with lived experiences around the world have played a key role in resisting marginalization and oppression. This has included questioning the past and present harms of involuntary psychiatric care. It is vital to recognize and elevate the work of organizations like Gerstein Crisis Centre that are grounded in this history and offer an approach to care that is non-medical, trauma-informed, and focused on harm reduction, information, choice, and consent.

For policy writers and legal advocates, this Gerstein Crisis Centre / Human Rights Watch case study offers a viable roadmap to provide safe and humane community-based care through rights-respecting services for individuals experiencing a mental health crisis. In many jurisdictions where under-investment and de-prioritization of rights-based community services are commonplace, this case study offers hope and guidance on transforming theory into practice. The work of Gerstein Crisis Centre foregrounds lived experiences throughout its approach and governance model. The Centre pushes beyond the all-too-familiar rhetorical deployment of “nothing about us without us” by continuously asking what it means to engage with people experiencing mental health crises and to transform the systems that purport to care for them.

This case study strives to do just that. It contains the frameworks, principles, and values needed to mobilize people and bring about fundamental change to mental health crisis care. Above all, it offers concrete guidance for how care practices can respect people’s autonomy and human dignity, as well as follow expertise that is based on lived experiences of mental health crises.

Marina Morrow is a Professor in the School of Health Policy and Management at York University. For over 20 years, she has worked collaboratively with psychiatric survivors, community-based organizations, and policymakers to surface the harms of biomedicalism and how neoliberal regimes reinforce individualist understandings of mental health over social and collective understandings of well-being.

Lucy Costa is the Deputy Executive Director of a rights-based service user-led organization in Toronto, Canada. Her work has involved educating and advocating a wide range of stakeholders, including police services, psychiatry residents, lawyers, and the public. She is the co-editor of Madness, Violence and Power: A Critical Collection.