Summary

Mejid Hedhli, 58, is serving a 122-year and 9 months sentence in Nadhour prison in Bizerte. This former contractor used to have a viable business and was even hired by the state to renovate a ministerial building in the historic Kasbah district of Tunis. His business provided a decent living for him and his family and employed dozens of construction workers.

Unforeseen events at the beginning of 2011 slowed down the project, resulting in financial losses that left him unable to pay his debts to several suppliers, to whom he had handed over checks, which he had pledged to pay on a timetable. But he could not fund those checks within that time, and so a public prosecutor initiated legal proceedings against him. He was arrested in 2015 and convicted in 2016 by a Tunisian court for dozens of unpaid checks that were due past the mutually agreed upon timing.

Acquiring goods from a supplier in exchange for a check to be cashed at a designated later date is a widespread practice in the Tunisian commercial sector. It enables both registered and unregistered entrepreneurs to carry out commercial transactions at a given time, even if they are unable to pay for the goods or services right away. [1] Under this practice, a supplier provides a merchant with an informal loan that is secured by a check intended to be cashed on a mutually agreed upon later date.

This practice allows merchants to carry out their transactions at any given time, even if they lack funds or the ability to obtain a bank loan or another form of credit. On the other hand, suppliers charge a disguised interest rate on the price of the goods or services because of the risks associated with accepting a check to be cashed later.

In some cases, the account holder may not have sufficient funds in their bank account to cover the check. In such cases, the bank may not honor the check and may return it to the payee unpaid. This is known as a bad check, a bounced check, or an NSF (not sufficient funds) check, and is considered as a criminal offence in Tunisia. The Tunisian Commercial Code punishes the writing of NSF checks with up to five years’ imprisonment. However, article 11 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), to which Tunisia is party, states that "no one shall be imprisoned merely on the ground of inability to fulfil a contractual obligation." Thus, it is a violation of international law to imprison a person solely for providing a check when they lack the means to fund it.

In Tunisia, the non-repayment of debts contracted via bank loans or a bill of exchange (lettre de change in French) would be litigated in civil courts, which are responsible for settling disputes between private individuals, rather than under criminal law. Debts contracted by check are an exception to this rule and are automatically open to criminal prosecution – and sometimes civil litigation on top of that. When three months elapse after a check is reported as NSF, a notification is sent to the public prosecutor, who is required to automatically take legal action against the issuer. Tunisian law punishes issuers of NSF checks as if they had committed fraud, that is obtaining financial or other benefit through deception.

According to the National Association of Small- and Medium-Sized Enterprises (ANPME), some 7,200 people are currently in detention due to NSF checks, nearly all of whom were entrepreneurs either in the formal or informal sector. While until recently there was no publicly available data on the number of people detained for NSF checks, the government said in a statement on May 22, 2024, that they were 496.[2] These people are incarcerated not because they refused to pay their debts contracted by check, but rather because they were unable to do so due to various circumstances (e.g: impact of Covid-19 on their business, significant delays in customer payments). According to the ANPME, genuine fraud does exist, but the cases are relatively few in number. Tunisian law makes no distinction between cases of fraud and insolvency.

The risk of imprisonment and the challenges faced by micro, small, and medium entrepreneurs in obtaining institutional loans led to the institutionalization of the “guarantee check” in the commercial sector. Very small enterprises (VSEs) and small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs), which account for 90 percent of Tunisian businesses, face major difficulties in accessing financing via the banking sector, especially when they lack collateral with which to guarantee a loan. The guarantee check provides them with an alternative path to bank credit.

According to ANPME, thousands of people are living in hiding in Tunisia, as they are wanted by the authorities for NSF checks, while thousands of others have fled abroad. Tough economic conditions have only aggravated the problem. Today, as Tunisia is undergoing a severe economic crisis, with significant inflation, a lack of liquidity, and heavy foreign debt, SMEs and VSEs are heavily impacted.

Successive governments have announced their willingness to change current legislation on checks to prevent entrepreneurs from ending up in prison for debt, but the reforms have yet to come through. Ali Kooli, former minister of economy, finance, and investment from September 2020 to August 2021 under prime minister Hichem Mechichi's government, announced on Tunisian television while in office that he was in favor of changing the legislation to introduce non-penal consequences for NSF checks, and declared that this was a priority for his ministry at the time. The Assembly of People's Representatives (ARP), Tunisia’s parliament, was considering an amendment to the Commercial Code to decriminalize bounced checks, before president Kais Saied suspended the body in July 2021 and eventually dissolved it in March 2022. President Saied has also proclaimed his willingness to change the law to decriminalize the writing of NSF checks and has on several occasions instructed justice minister Leïla Jaffel to introduce a bill to this effect.[3]

Imprisonment for bounced checks not only deprives an indebted person of their freedom, but also has a devastating effect on their families, whose living conditions deteriorate because of imprisonment, or if the indebted person decides to flee abroad or live in hiding to avoid prison. Indebtedness also has physical and mental health consequences for those in debt and their relatives.

The courts, for their part, tend to handle cases of NSF checks expeditiously. They tend to demand payment of the full amount of the debt, plus any additional fees, without offering any alternatives to imprisonment. The judge rarely examines the circumstances that led to the merchant's financial impasse or proposes repayment plans. Each NSF check is the subject of a separate decision by the judge, and prison sentences are cumulative, resulting in instances of people being sentenced to several decades in case of multiple checks that defaulted. In addition, indebted people rarely have access to effective legal representation, either due to lack of means or out of resignation when faced with the inability to settle the debt. If a debtor pays his debt before the court pronounces a verdict, the prosecution is halted.

Imprisonment for NSF checks is also counterproductive as it rarely leads to the creditor's repayment and in cases where repayment is made, it is generally due to pressure on the debtor's family to come up with funds and leads to many entrepreneurs going out of business. It also costs the state money, in court and prison costs, causes backlogs, and contributes to prisons overcrowding. In France, the decriminalization of issuing NSF checks in 1991 was described as a success after just two years of implementation, as it led to a reduction of irregular and NSF checks, thanks to a banking prohibition mechanism and preventive measures to avoid the non-regulation of NSF checks. Mauritania, where the use of “guarantee checks” was commonplace, reformed its commercial code in 2020 to decriminalize the issuing of NSF checks to promote the protection of human rights and improve the business climate.

In Tunisia, even the largest employer organization, the Tunisian Confederation of Industry, Trade and Handicrafts (UTICA), which long opposed to the decriminalization of issuing NSF checks, reviewed its position in 2023. The organization recommended the introduction of preventive mechanisms to avoid the non-payment of issued checks, rather than imprisonment as a coercive measure.

Tunisia should repeal article 411 of the Commercial Code, which allows imprisonment for debts contracted by checks, and adopt legislation in line with international standards, providing alternatives to imprisonment and sustainable means for creditors to recover their debts. The Tunisian authorities should also adopt a law that allows individuals to file a declaration of personal insolvency when they are unable to repay their debts, based on international best practice. Pending the rapid implementation of these measures, the authorities should continue to apply the presidential pardon, declared on February 10, 2022, on the fine levied by the state on those who pass NSF checks, and extend it beyond the deadline already set for December 2023.

The authorities should release those imprisoned for unpaid checks simply because they were unable to pay them, allow their rehabilitation, and support them to come up with a plan for settling their debts. The justice system should assess the socio-economic situation of indebted people and the reasons for their financial difficulties in all decision-making and encourage out-of-court settlements between debtors and creditors or the implementation of repayment plans. The Tunisian Order of Lawyers and organizations specializing in legal aid should provide assistance to indebted people who cannot afford to hire a lawyer.

The Central Bank and other economic players should promote solutions to make checks a more secure tool and promote access to financing for SMEs and VSEs. Donors and international financial institutions should provide Tunisia with technical assistance to develop reforms to decriminalize bounced checks and put in place corporate and individual insolvency laws that can relieve the debts of people unable to regularize their NSF checks.

Glossary of Acronyms and Abbreviations

ANPME - National Association of Small- and Medium-Sized Enterprises; in French, Association nationale des petites et moyennes entreprises.

ARP – Assembly of People’s Representatives.

GDP – Gross domestic product.

IMF – International Monetary Fund.

INS – National Institute of Statistics.

NSF check – A check with “not-sufficient funds.”

SMEs – Small and medium-sized enterprises. In Tunisia, the National Business Directory (in French, Répertoire national des entreprises, RNE) distinguishes between micro-enterprises (less than 6 employees), small enterprises (between 6 and 49 employees) and medium-sized enterprises (between 50 and 199 employees). Companies with more than 200 employees are considered large enterprises. In this report, we refer to SMEs as companies employing between 6 and 199 people.

UTICA - Tunisian Confederation of Industry, Trade and Handicrafts.

VSEs – Very small enterprises. In this report, we refer to VSEs as companies employing less than 6 people.

Recommendations

To the Tunisian Government and the Tunisian Parliament

Repeal article 411 and other provisions of the Tunisian Commercial Code, which stipulates the imprisonment of issuers of NSF checks without any distinction between a person refusing to pay and a person unable to pay;

Pass legislation that complies with international standards and does not result in imprisonment for debt, meaning legislation that does not automatically consider unpaid checks as fraud, but rather takes into account the reality of the check's use as a financing tool in the Tunisian commercial sector, provides for alternatives to imprisonment, and sustainable means for creditors to recover their dues. The legislation should require the judiciary to assess whether there is willful refusal or a genuine inability to pay;

Pass legislation that allows for individuals to file a declaration of personal insolvency when they are unable to repay debts in lieu of imprisonment. Such a scheme should follow international best practices;

Consider extending the presidential pardon for the fine on the amount of the unfunded check due to the state in order to alleviate the burden on debtors and facilitate the repayment of creditors.

To the Ministry of Justice

Release people unjustly imprisoned for issuing bounced checks because they were unable to repay their debts and allow their rehabilitation with the establishment of a debt repayment plan;

Instruct the judiciary involved in debt claims to assess the socioeconomic status of borrowers and their ability to pay, and work with creditor and borrower to set a repayment plan based on the borrower’s financial capacity. Any repayment plan, asset seizure, or wage garnishments should protect the borrower’s basic economic rights and protect their ability to procure basic necessities;

Where the judiciary finds that an individual is willfully refusing to repay debts, it can initiate criminal fraud proceedings that may include imprisonment.

Instruct the judiciary to require a meeting with the borrower and provide her/him with an opportunity to dispute the claims presented by the creditor or mount a defense.

To the Central Bank of Tunisia

Promote reforms to decriminalize bounced checks;

Propose solutions to secure checks as a means of payment and promote the development and use of other secure and reliable payment methods;

Allow more low-income individuals to access the regulated credit system so that they are less likely to resort to informal lending systems.

To International Partners and Financial Institutions

Urge Tunisia to repeal article 411 and other provisions of the Commercial Code, which in practice allow imprisonment for debt;

Support Tunisia-based non-governmental organizations that specialize in legal aid to provide pro bono support to borrowers who are unable to afford legal representation.

Provide assistance to Tunisia to implement a reform to decriminalize the issuing of NSF checks in compliance with international law, put an end to imprisonment for debt, and minimize negative impacts on the economic activity and the rights of indebted individuals and creditors.

Provide technical assistance to Tunisia to develop personal insolvency procedures that allow for effective debt relief and empower an individual who is unable to repay their debt to be economically productive, including criteria that require relevant authorities to assess an individual’s ability to repay.

Methodology

For this report, we documented the cases of 12 people prosecuted for bad or NSF checks, including people imprisoned, or others living in hiding in Tunisia or in exile. We also interviewed three Tunisian lawyers who have often represented clients for unpaid checks, a judge, as well as two experts on the entrepreneurial sector in Tunisia, two experts on the banking system, and a researcher in political economy.

A total of 20 mostly in-person interviews were conducted between May 2022 and January 2024, in the regions of Tunis, Gabès, and Bizerte, and some by phone. We interviewed seven indebted people living in hiding in Tunisia, including four women, the families of three imprisoned people, and two indebted people living in exile.

There is little data publicly available on the use of checks as a lending tool and the consequences of prosecutions for unpaid checks in Tunisia. However, the report is also based on an analysis of national commercial laws and practices.

We also benefited from the expertise of the National Association of Small- and Medium-Sized Enterprises (Association Nationale des Petites et Moyennes Entreprises, ANPME), a professional association of entrepreneurs created in July 2020 that advocates, among other activities, for the decriminalization of bounced checks in Tunisia.

All interviews were conducted in Arabic or French. Human Rights Watch explained the purpose of the interviews to interviewees and obtained their consent to use the information they provided in this report.

In some cases where interviewees asked not to be named or where we assessed that naming them could jeopardize their security, we have used pseudonyms and have withheld potentially identifying information.

Human Rights Watch wrote letters, annexed to this report, to the justice ministry in January 2024 and the General Directorate of Prisons and Rehabilitation in February 2024, requesting information for incorporation into this report or meetings with officials, but did not receive any reply at the time of publication.

I. Background

Officially, imprisonment for debt does not exist in Tunisia. Yet, over 496 people are currently imprisoned for writing bounced or NSF checks, according to official figures. In fact, imprisonment for writing NSF checks in Tunisia is a disguised, long-practiced form of imprisonment for debt.

On May 22, 2024, the prime minister’s office said in a statement that 496 people were behind bars for NSF checks, 292 of whom were convicted and 204 were in pre-trial detention.[4] The ANPME however, gives a much higher estimate of up to 7,200 people.[5] According to the association, several thousand more people living in hiding in Tunisia or in exile are also sought by the authorities for NSF checks.[6]

The use of checks is not without penal risk, since writing a bad check is punishable by up to five years prison and a heavy fine under the Tunisian Commercial Code, which makes no distinction between those who write an NSF check intending to deceive and those who write a check in good faith but are simply unable to fund it.

The check is often used as a kind of guarantee by its issuer. It is provided as an advance on goods or services with the understanding that it will not be cashed immediately, but that the check-issuer will repay the creditor by cash, check, bank transfer or other means at a later stage, according to a mutually agreed timetable. This “guarantee check” is therefore used as a financing tool for individuals and businesses who do not have the cash for their transactions and who in Tunisia would not usually qualify for loans from banks or other institutions that require substantial collateral. This is commonplace among VSEs and SMEs, which often rely on check transactions for their entire operations.[7]

When a bank refuses to process a check on the grounds of insufficient funds, and the check-writer does not fund the check within three months, the bank then notifies the public prosecutor, who is required to initiate criminal proceedings against the person whose check was rejected. That person could end up behind bars, not because they are unwilling to pay the amount of the check plus fees (bank fees, interest, and a fine), but because they are unable to.

Imprisonment has serious consequences for debtors and their relatives alike, and causes wider economic harm, including, often, for the creditors themselves.

The excessive use of checks in Tunisia is closely linked to the macroeconomic situation of the country and to the socio-economic environment in which VSEs and SMEs operate.[8]

Tunisia’s Economic Overview

Since Tunisians ousted authoritarian president Zine El-Abidine Ben Ali in 2011, the country has faced a slump in growth, in addition to political instability and the failure of successive governments to protect the economic rights of all. Since 2020, the Covid-19 pandemic and the Russia-Ukraine war have exacerbated economic hardships.[9]

Tunisia’s public debt represented about 80 percent of its gross domestic product (GDP) in 2022.[10] The unemployment rate was 15.8 percent in the third quarter of 2023, according to the National Institute of Statistics (INS). During the same period, unemployment reached 39.1 percent among the labor-force aged between 15 and 24 years, and up to 24.6 percent among graduates of higher education.[11]

Tunisia is increasingly relying on external financing to close the gap between revenues and expenditures. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), Tunisia’s debt trajectory is “unsustainable unless a strong and credible reform program” is adopted by the authorities.[12]

In October 2022, the IMF and Tunisia reached a staff-level agreement on an Extended Fund Facility (EFF) of about US$1.9 billion over 48 months, but president Kais Saied appears to have ultimately rejected the deal.[13] On April 6, 2023, president Saied denounced the conditions of the loan as “Diktats from abroad, which only lead to further impoverishment, are unacceptable.”[14] The IMF deal is conditioned on Tunisia committing to a series of reforms – including the privatization of certain state-owned enterprises, a reduction in the civil service wage bill, the gradual lifting of subsidies on basic goods and energy, and tax reform – for which the IMF expects a firm and immediate commitment from the Tunisian authorities.

The prospect of a new IMF loan indeed raises concerns,[15] as its conditions and proposed austerity measures could undermine the economic and social rights of Tunisians and further exacerbate inequalities.[16] However, without reforms, Tunisia remains in a precarious economic situation, even though the immediate economic crisis appears to have subsided.

For its 2024 budget, Tunisia has forecast a 70 percent increase in external borrowing, but its creditors are dwindling. Several long-standing donors, such as the European Union and EU member states' development agencies, require prior agreement with the IMF.[17]

Saied, who was elected in September 2019, has focused more on implementing his own political roadmap since July 2021, including the dismantling of Tunisia’s democratic institutions, the adoption of a constitution granting him extensive powers and the election of a new parliament with limited prerogatives,[18] than on effectively addressing the economic crisis. [19]

Situation of Small and Medium Businesses

Nearly 800,000 VSEs and SMEs,[20] which include businesses with under 200 employees and account for over 90 percent of all businesses in Tunisia,[21] operate within this challenging economic context. According to the INS figures for 2018, SMEs account for 50 percent of Tunisia’s GDP and provide more than 70 percent of formal private-sector jobs.[22]

Despite playing a central role in the national economy and contributing significantly to job creation, these businesses face many challenges, including red tape, a limited use of digital tools, and a lack of access to financing. According to business surveys conducted by the World Bank, 43.9 percent of firms considered the lack of access to funding to be a major constraint in 2020, compared to 21.9 percent in 2013.[23] According to the president of the Tunisian Association of Capital Investors (ATIC), half of Tunisian SMEs have serious financial difficulties.[24] SMEs that do have access to funding usually obtain short-term credit, due in part to the lack of long-term liquidity in the banking sector, the World Bank said.

These enterprises have been significantly impacted by the economic slump that accompanied the Covid-19 pandemic. According to the ANPME estimates, 200,000 VSE and SMEs went bankrupt in four years, between 2019 and 2023.[25] A study of the African Development Bank indicates that 65 percent of VSEs and SMEs saw a significant decrease in revenues between 2019 and 2020.[26]

II. Inadequate Legislation and Poor Economic Environment

Checks as Credit Tools in Challenging Economic Environment

The check, which is normally used as a means of direct immediate payment, is often used in Tunisia as a guarantee for an agreed future payment either as a lump sum or in installments.

According to Abdelkader Boudrigua, a finance expert and professor at Carthage university, this practice is widespread in Tunisia among individuals (both those with and those without bank accounts)[27] and businesses when they lack access to bank loans.[28]

Some of those who hand over guarantee checks are people who have no bank account and therefore cannot qualify for financing from a bank. In Tunisia, 37 percent of the population held a bank account in 2021, including 29 percent of women.[29]

To finance a need, a person without a bank account can provide as a guarantee a check signed by relatives or other third parties. It is usual for checks to circulate for a period up to 24 months[30] and often without naming the beneficiary, Boudrigua explained. In such a case, beneficiaries are often people with low incomes, who may need funds for personal expenses or to finance an income-generating activity.

Both individuals and businesses with bank accounts may still resort to a guarantee check because they cannot access credit from the bank due to their poor self-financing capacity, meaning they do not generate sufficient income for the company’s operations, or because they have reached their debt limit.

In the commercial sector, the use of the check as collateral for payment in installments (in the form of delayed payment) is most prevalent among VSEs and SMEs. It is used in all sectors, from agriculture to construction, in sales and event management, in both the formal and informal economy.

More concretely, in commerce, the transaction is usually between a supplier and a purchaser/customer. The client wishes to purchase goods or services but cannot pay in cash, so he gives the supplier one or more checks as guarantee, to be cashed after a certain period of time.

The agreement between the supplier and his purchaser is informal and trust-based. The check is preferred to other means of payment or guarantee by the purchaser since it requires merely obtaining a checkbook. Suppliers consider it more secure than other financial transaction tools such as bills of exchange, because of the prospect of prison hanging over the borrower if they fail to fund the check. [31]

For Abderrazak Houas, spokesman for the National Association of Small- and Medium-Sized Enterprises (ANPME), “the specter of prison is what undergirds the trust between the supplier and his customer. The check therefore offers a strong guarantee of payment.” [32]

Check financing often involves high interest rates, sometimes as high as 40 percent. In fact, the commercial practice in Tunisia requires sellers to display the price of merchandise, a price that they tend to discount if the client pays cash. This differential is a disguised interest rate that covers the resources and risk costs for the supplier, said Boudrigua.[33]

While primarily used for commercial transactions between suppliers and purchasers, the check is also used as a means of guarantee for monetary loans unrelated to commercial transactions. In this case, private individuals lend money using checks from the borrower as collateral, and usually charge high interest. This practice forms part of a parallel banking system. In this report, we have only considered the use of checks for strictly commercial transactions.

Problematic Legislation

A disclaimer is printed on the last page of all checkbooks in Tunisia. It reads:

Because checks serve as means of payment, their issuance presupposes that the drawee banker has sufficient and available funds in advance. Issuing a check in the absence of such a provision constitutes a serious offense punishable by the penalties for fraud: 5 years’ imprisonment, plus a heavy fine, and various additional penalties, including a ban on holding checkbooks for 1 year.”[34]

This heavy penalty of five years imprisonment for unpaid checks is provided for in articles 410, 411 and 412 of the Tunisian Code of Commerce.[35] The application of these provisions amounts in practice to imprisonment for debt, even though imprisonment for debt conflicts with international human rights law.

Article 11 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), to which Tunisia has been a party since 1969, stipulates that “no one shall be imprisoned merely on the ground of inability to fulfil a contractual obligation,” including in the event of non-payment of a debt.[36]

Tunisian law equates indebted people’s inability to repay with fraud, without making a case-by-case distinction between those who are unable to pay their debts on time for various compelling economic reasons and those who have used the check with fraudulent intent.

The last page of the Tunisian checkbook also states:

Any check issued without sufficient funds is automatically brought to the attention of the prosecutor for prosecution. However, such proceedings will be suspended if the drawer can prove that the check has been paid or that sufficient funds are now available to cover the check, and that a fine has been paid within the legal time limit.[37]

When a check that lacks sufficient funds is presented for payment, the bank is legally required to notify, on the same day, the check issuer, who has three business days to provide sufficient funds, before starting to incur fees. After these three days, and during the following four working days, the bank sends an official notification to the issuer of the unfunded check via a bailiff. In addition to paying the check, the issuer must pay the bailiff's fees for the notification, which amount to between 80 and100 Tunisian dinars (approximately US$25 to 32) and an interest of 10 percent of the check’s value.[38] After seven working days, the issuer of the unfunded check must pay a fine to the state of 20 to 40 percent of the amount of the check in addition to the principal amount.

If, after 90 days, the principal amount of the NSF check, a 20 to 40 percent fine, and other additional charges have not been paid, the bank is required to notify the public prosecutor, who is required by law to automatically initiate legal proceedings against the check’s issuer. Proceedings are dropped only if the check, fine and other fees are fully paid before the trial ends.

Prison sentences for bounced checks are cumulative. If the debtor is unable to settle his debts and is convicted of passing several NSF checks, he will serve a sentence equivalent to the sum of the different convictions. Human Rights Watch interviewed the family of one prisoner who was sentenced to 122 years and nine months in prison for dozens of unpaid checks.

The 20 to 40 percent fine on NSF checks, the interest on the check’s value and other fees are an additional burden for people who are already unable to repay their debts, especially when the person has several unpaid checks to repay. Even if the indebted person manages to pay what they owe to their creditor, if they fail to pay the other charges, the prosecution goes forward, and they may still end up behind bars.

Decree-law No. 2022/10 of February 10, 2022,[39] issued by president Kais Saied under the exceptional powers he granted himself on September 22, 2021, [40] provides a presidential pardon on the fine collected by the Tunisian state, to anyone who issued a bad check before the decree was issued, and who has paid the full amount of the check, as well as the related bank fees or notice of protest fees, before December 31, 2022, which are generally in the range of 80 to 150 Tunisian dinars (approximately US$25 to 46). A second decree-law issued on December 30, 2022, extended this deadline to December 31, 2023.[41]

Tunisia's bankruptcy regime was modernized with the adoption of the Collective Proceedings Law of April 29, 2016,[42] regulating business restructuring and bankruptcy. The new law, which simplified bankruptcy procedures, was aimed to promote business rescue and decriminalize bankruptcy to improve creditor confidence and promote entrepreneurship, according to World Bank documents.[43]

However, the law did not address the criminalization of bounced checks. When a person writes a check for the sake of a registered company and this check is rejected, only the individual’s criminal liability as the check-issuer is engaged.[44]

In addition, Tunisia lacks a personal bankruptcy law (or personal bankruptcy procedure) that would provide relief for debtors facing economic hardship, including entrepreneurs in the informal sector.

Trapped in Debt Cycle

Interviews carried out by Human Rights Watch show that after the bank rejects a first check, the debtor often faces spiraling costs in fines and fees, and, sometimes, writes additional checks that they cannot cover. They may also face the cost of hiring a lawyer and the taxes owed by the business even if it is at a standstill. The crushing debt problems often lead to the business shutting down entirely, thus leaving the debtor, and sometimes the debtor’s entire family, without a source of income.

After facing prosecution for unpaid checks, all nine indebted people interviewed by Human Rights Watch were forced to cease their commercial activities as small business owners and live in constant fear of arrest. Two of them resorted to working as day laborers to provide for their families’ most basic necessities.

In the absence of alternatives such as reimbursement plans, some indebted individuals may resort once again to using checks, but this time signed by their relatives. One person interviewed by Human Rights Watch used his wife's checks to try to keep his work as an agricultural technician going after several of his checks bounced.

It is often the family or friends of the indebted person who come to their rescue, putting part of their assets up for sale, or taking out loans themselves, and in some cases resorting to using checks as well.

“Zeineb,” 48, is a pastry chef who had her own business in Lafayette, in the center of Tunis. She was paying her suppliers of equipment and ingredients by cash and with checks.[45] While business had been slow for several years, the Covid-19 crisis dealt a severe blow, she said. At the beginning of 2020, she had her first check rejected. Shortly after, others followed. She said that some of her suppliers had cashed her checks before the agreed date, but in any event, during the Covid-19 pandemic lockdown she was not earning enough to pay dozens of checks. And while her debt was mounting given the fees incurred by unpaid checks, a prosecutor filed charges against her.

On February 7, 2023, Zeineb was arrested for writing NSF checks and sent to Manouba prison in Tunis. Her mother and her two sisters sold all of Zeineb's furniture and their own gold jewelry to pay off the part of the debt for which she had been imprisoned – around 100,000 Tunisian dinars (approximately US$31,500). Zeineb, who lost her business and her home as a result, moved in with her mother, and is supported by her family. She is still being prosecuted by the authorities for other NSF checks.

Zeineb said she tried, unsuccessfully, to agree with her creditors on a repayment plan. “My providers refused any arrangement I suggested. Some of them thought I was trying to scam them, while others tried to take advantage by setting their own terms,” she said.

“Rachid,” who owned a transport company for building materials in one of Tunisia’s coastal cities, also spent a month in prison due to NSF checks, before his sister, a teacher in the public sector, took out a bank loan (consumer credit) to repay around 8,000 Tunisian dinars (approximately US$2,500) to one of her brother’s suppliers, who then agreed to sign an attestation of payment for some of the checks for which Rachid had been imprisoned.[46]

According to Houas, as soon as a first check is declined, the check-writer faces a greater risk of more debt piling up. This is because a bounced check destroys the confidence that suppliers had in the borrower, leading them to cash other checks they may be holding from this borrower, regardless of the borrower’s ability to fund the checks and counting on the pressure from the bank and the threat of imprisonment to ensure payment. They fear that if they instead wait until the agreed-upon payment date, the borrower by that point may have gone to jail or fled into hiding.

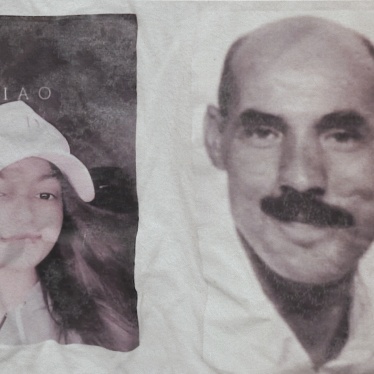

Mejid Hedhli: Sentenced to 122 years and 9 months in prison for bounced checks

Jalila Hedhli is a mother of three: Siwar, 20, and Meriem, 9 and Seif, 26. Her husband, Mejid Hedhli, 58, is a building contractor who in 2016 was sentenced to 122 years and 9 months in prison for unfunded checks.

Mejid has been in prison since April 2015. Meriem barely knows her father. Siwar writes letters and poems to him and has appeared on various TV shows to denounce his long sentence for debt and call for his release.

In 2010, Mejid Hedhli was hired by the education ministry to renovate a building in the Kasbah quarter of Tunis, where several government ministries are located, including the office of the prime minister. At the beginning of 2011, after the uprising ousted authoritarian president Zine El-Abidine Ben Ali in 2011, protesters occupied the Kasbah square to protest the government that succeeded him, forcing Mejid Hedhli’s company to halt its work. According to Jalila, they suffered significant delay, as well as damage to their equipment, but completed the project in 2013.

She told Human Rights Watch that the education ministry did not pay Mejid the third installment due for his project, amounting to around 400,000 Tunisian dinars (approximately US$127,000), which would have allowed him to fulfill his commercial obligations.

Like many entrepreneurs in Tunisia, Mejid Hedhli obtained materials from suppliers by providing them with checks to be used as guarantee for later payment in installments. Due to the circumstances, he found himself unable to repay his debts and had about 50 checks rejected, the total value of which was around 300,000 Tunisian dinars (approximately US$95,000).

In April 2015, Manouba Court first sentenced Hedhli in absentia to a total of 300 years in prison, according to his wife. Then, in 2016, he was sentenced by the same court to 122 years after his family presented proof of payment (payment attestations – شهادات خلاص, in Arabic) for a portion of the checks. Some of his suppliers agreed to sign these attestations to help him, his wife said.

Mejid Hedhli attempted to secure a bank loan to repay his debt, but the bank refused due to the bounced checks. His company, employing dozens of people including an accountant, a secretary, and several engineers, did not shut down after his arrest. Instead, ownership was transferred to one of his colleagues even before he was sentenced.

Following Hedhli’s arrest for bounced checks, his family could not afford a lawyer. A court-appointed lawyer in 2014 filed a complaint against the Education Ministry regarding the payment claimed by his company. As of June 2024, Hedhli was still waiting for a hearing to be scheduled in this case.

Imprisoned first in Mornaguia prison in Tunis, he was moved to Nadhour prison in Bizerte in February 2023.

Jalila, who had not been working when her husband was still free, has found employment at a bakery. Siwar now attends university in Sfax, south of Tunis, and is no longer able to visit her father frequently.

The family has submitted at least a dozen requests for a presidential pardon. Two of them were taken into consideration and reduced his sentence by a few decades. Mejid Hedhli, who has developed diabetes during his long, 9-years incarceration, holds little hope of regaining his freedom. “He thinks he will die in prison,” Jalila said.[47]

III. Consequences of Imprisonment for Bounced Checks

Deteriorating Living Standards

Imprisonment or the threat of imprisonment for an NSF check inhibits the ability of a person to earn income to repay the debt. It also impacts the debtor’s family and professional circle, placing others in a precarious situation.

In many cases, the detention of a business owner leads to the cessation of business activity, including the dismissal of employees. The looming threat of imprisonment, meanwhile, drives people to go into hiding or flee the country, thus often putting them, and sometimes others, out of work.

If the indebted person is a family’s sole wage-earner, prison, or the threat of it, can economically devastate the entire household.

Human Rights Watch followed twelve cases of people who were unable to fund checks to reimburse a debt. Of the twelve, three are currently imprisoned, seven remain in hiding in Tunisia for fear of being apprehended by the authorities, and two have fled abroad. Among those in hiding or exile, three have served short prison terms for bounced checks. Eight out of the nine people have ceased all commercial activity following their prosecution and are struggling economically. Two of those living in hiding in Tunisia were the main breadwinner of the family and now work as day laborers to support their household. Among them, only one of the exiled individuals resumed a commercial activity, but from abroad.

“Syrine” and her sister “Amina” used to run an event management company. Both ceased working since 2015 due to their inability to clear debts incurred from organizing an event that ultimately failed to take place due to circumstances beyond their control, they explained.

“Syrine” said:

I had to move back in with my parents, along with my two kids. My son has a heart condition, and for two years I haven't been able to take him to the cardiologist for a check-up. A private doctor is expensive, and on top of that, I can't go to hospital, I'm afraid [of being arrested].

My daughter should be attending nursery school, but I can’t afford the monthly fee between 150 and 180 Tunisian dinars (approximately US$48 to $57). Next year, she must go to preparatory school, so I will have no choice but to register her.[48]

In many cases, the risk of imprisonment directly affects the enjoyment of human rights, including access to basic services such as health care, housing, education, and administrative services. It also affects people’s mobility inside and outside Tunisia.

According to the ANPME, police do not actively search for persons accused of writing unfunded checks to arrest them, but they still risk arrest if they are stopped at a checkpoint or during any routine police control in the street.

The problems resulting from debt are compounded by the shortcomings of Tunisia's public services and social security system, which do not adequately guarantee people's economic, social, and cultural rights.

In addition to the impact on the household, the debts can also become a burden for the debtor’s extended family. Often, members of the family step in to help repay part of the debt, to shelter family members who have lost their homes, or to provide for their daily needs. Sometimes, the family's assets are sold in an attempt to pay off or reduce the debt, or a member of the family takes a loan to help the debtor financially.

“Zeineb”, 48, owned a pastry shop that she had to close after business slowed down during the Covid-19 pandemic, saddling her with heavy debt. With no income, she is now entirely reliant on her family for support.

After the revolution [of 2011], the economic situation started to decline, but the Covid pandemic brought us to our knees. I had to relinquish my store after the summer of 2020. I had given checks to my suppliers that I could not fund, and so they bounced. At first, I attempted to work from home a little bit but eventually stopped all activity. I no longer had the baking equipment to do so, I sold it.[49]

Zeineb was arrested on February 7, 2023, after some of her checks bounced, then released on February 27, 2023, after her family scraped together enough to secure her release.

When I went to prison, my mother and sisters sold all my furniture and their gold jewelry to pay off part of my debt, the equivalent of 100,000 Tunisian dinars [approximately US$31,500]). One of my sisters even sold her car [...] Today, I am back to living with my mother, and she and my sisters are covering all my living expenses.[50]

“Rachid”, a truck driver and entrepreneur who was jailed in January 2016 for NSF checks, was also able to recover his freedom thanks to the financial help of his family. "My sister, who is a teacher in the public sector [a civil servant], took out a bank loan to be able to pay my supplier around 8,000 Tunisian dinars (approximately US$2,500),” he said. “That way, he signed certificates showing that some of my checks had been paid.”[51]

This enabled “Rachid” to leave prison after a month, but soon after, he was wanted again, for other NSF checks. He is unable to find a stable job and has been able to find only day-to-day work in the informal sector, barely earning enough to support his family, he said. “I’m reaching a dead end and considering leaving the country by boat for Europe,” he added.

Studies conducted in other contexts have shown that debt can have negative consequences on the health of indebted people, and sometimes even their family members, further exacerbating their difficulties.[52]

A World Bank study on personal insolvency issued in 2014 stresses that over-indebtedness leads to “serious psychic, and ultimately physical, problems for debtors” due to anxiety and their inability to manage debts, stating that “policymakers around the world have concluded that relieving the long-term pain and suffering of these debtors is a worthy goal in and of itself.”[53]

Among Human Rights Watch interviewees, one indebted entrepreneur living in hiding and one relative of an imprisoned entrepreneur said they faced mental health issues due to the debt problem.

Living in Exile

Given the risk of imprisonment for issuing NSF checks, thousands of business owners have chosen exile, according to ANPME estimates.[54] Many of them choose Algeria, Morocco or Libya, countries they can access without a visa. Human Rights Watch spoke with two former entrepreneurs in exile. One of them, who owned a textile factory in the Cap Bon region in northern Tunisia, now lives in Morocco where he is unemployed, while the other, who owned a company that sold wood in Tunis, is now in Algeria where he has resumed commercial activities. Both told Human Rights Watch they left Tunisia because they had no sustainable solution for repaying debts and had no other way to avoid prison.

“Bilal”, who owned a textile production factory and clothing stores, has been in Morocco since 2023. In Tunisia, he was imprisoned from December 2022 to March 2023 for a series of unpaid checks. Bilal said that his financial problems began in late 2018, when a check that he had written to a fabric supplier was rejected by the bank. Bilal claims that, at the time, his supplier had cashed the check earlier than agreed between the two parties. This incident hurt his company and the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020 worsened its situation, leading Bilal to temporarily close the factory and stores.

“Covid-19 was like a tsunami and you couldn't do anything: you couldn't sell your products, settle your debts or meet the bank's demands. My debt reached 400,000 Tunisian dinars [US$126,000],” Bilal said.[55]

Once Bilal went to prison, his family worked to find solutions and secure his release.

“My brother sold off some of the company’s assets that I owned, at a great loss of course, but this enabled him to raise enough money to pay off most of the debt and obtain payment certificates. At the time, I was on the hook for unpaid checks totaling 120,000 Tunisian dinars [US$37,800]. My brother was able to gather 80,000 Tunisian dinars [US$25,000],” he said.[56]

The judge agreed to release Bilal since the remainder of his debt was owed to the Caisse Nationale de Sécurité Sociale (CNSS), a Tunisian social security institution. The court subsequently ordered seizing his manufacturing equipment to pay off this part of the debt.

"Once I got out of prison, I was disgusted. I set up a business and I made a mistake. But that's no reason to go to prison,” Bilal said.[57]

Bilal employed over 200 workers, he said. While some of them quickly found employment in other factories, others found themselves suddenly unemployed as a result of Bilal’s business closure.

Bilal left his family back in Tunisia, including his children. In Morocco, he has no job and has not found a way yet to help support his family. Under these circumstances, he is also unable to repay his creditors.

“Sofiane”, owned a wood sales business, but when he got caught in financial difficulties in 2014, he ceased operations, and in 2016, decided to leave Tunisia to avoid prison and traveled to Algeria. At that time, he owed 200,000 Tunisian dinars (approximately US$63,000) to a supplier, among other debts. Sofiane tried to settle the debt out of court, but after failing to agree with the supplier on the terms, he fled the country.

“I couldn't sell what wasn't entirely mine and squander my entire family's assets to pay a supplier,” he says.[58]

In Algeria, he resumed a commercial activity in catering and was able to pay off around 180,000 Tunisian dinars (approximately US$56,500) in debt he owed to various other suppliers in Tunisia, around half of his total debt.

Fearing prison, Sofiane refuses to return to Tunisia, where his family lives. In Algeria, despite his commercial activity, his situation is precarious. He was unable to renew his expired Tunisian passport while he was in Algeria, due to the criminal proceedings against him in Tunisia. Without a valid passport, the Algerian authorities prevented him from renewing his residency in January 2023 and ordered him to leave the country. Following a change in Tunisian procedures, Sofiane was finally able to renew his passport at a Tunisian consulate in Algeria in October 2023, but the order to leave Algeria still hangs over him and his business.[59]

Undermining the Right to a Fair Trial

Normally, in Tunisian courts, a single judge within each jurisdiction deals with cases involving bad checks. It is customary for the judge to rule immediately. If a person is prosecuted for several checks, the judge rules on each case separately. While the penalty for each offence may be up to five years' imprisonment, the judge can exercise discretion based on the amount of debt owed on each check. The penalties for bounced checks are cumulative.

In most cases, trials for bounced checks are quick. The judge, who usually holds a document listing the checks to be paid by the issuer and a copy of the signed checks, generally asks the issuer, when they appear before the judge, if they are indeed the issuer of the check, and whether the check had been paid in the meantime. The issuer may present the judge with one or more certificates of payment, which will put an immediate end to the proceedings.

Because the issuing of NSF checks is considered a formal offence,[60] the judge is required to rule on the commission of an offence without considering the intention of the check issuer, explained judge Abdessetar Khlifi.[61]

If the check has not been paid, then the judge does not try to examine the circumstances that led to the indebtedness, but immediately orders the issuer to be taken into custody, says Houas, spokesman for ANPME. “Bankruptcy [even when declared by a judge] is not an extenuating circumstance in this situation,” he says.[62]

The judge is called upon to rule on the debt incurred with a creditor rather than to find alternative solutions for debt repayment, such as a repayment plan or other mutually acceptable out-of-court solutions. Because the outcome is almost a foregone conclusion, people in debt prefer not to go before the judge to avoid arrest, while trying to find an informal way to settle their debts.

Among the 12 people whose cases we followed, only 3 hired a lawyer for their defense. Very often, people in debt do not hire lawyers because they cannot afford to, or because they prefer to use what remaining money they have to pay off their debts, whereas some have told Human Rights Watch that they feel that their fate is already sealed.

The poorest don’t even have a choice. “In addition to legal assistance expenses, there are numerous other costs associated with accessing justice which constitute a major barrier for the poor, who simply cannot afford those expenditures,” according to a UN expert on extreme poverty.[63] These costs may include transportation, accommodation, administrative formalities, etc.

Yet, the lawyer's presence before the judge can be important, particularly when it comes to requesting a deferral of the hearing and giving the debtor more time to raise the required sum.[64]

Tunisian law allows people held in police custody prompt access to a lawyer and to legal assistance while in detention, yet police officers often fail to notify detainees and their families of their right to legal representation.[65] Exceptions in the regulations governing free legal aid mean that people detained for bounced checks almost never benefit from it, according to Houas of the ANPME.[66]

IV. Ineffectiveness of Debt Imprisonment

Difficulty of Debt Collection

Imprisonment for debt is supposed to encourage debt compliance. Its proponents claim that it is the most effective way to force people who lack collateral to repay their debts.[67]

In reality, however, this practice is often ineffective in addressing the right of creditors to be reimbursed. Deprivation of liberty is equivalent to a double penalty for those debtors who have not acted fraudulently, because it denies them a source of income and, thereby, the most viable path to paying off their debts.

Most European countries abolished debt imprisonment at the end of the 19th century following widespread recognition of its ineffectiveness as a debt collection mechanism.[68]

According to a 2017 World Bank study, “Even debtor’s prison is not a sure method of coercing debtors to pay, and the tragic irony of imprisoning debtors in order to goad them into working to pay creditors ought to be obvious. Imprisonment for debt was abandoned in most areas … it was spectacularly ineffective in producing payment for creditors.”[69]

In 2020, a group of Tunisian members of parliament (MPs) had proposed a bill to decriminalize the writing of NSF checks, arguing that the current legislation was repressive and harmful in many respects.[70] However, the bill has not been discussed by the ARP since president Saied dissolved the body in March 2022.

In the preamble to the draft bill, the MPs had argued that in most cases, imprisonment does not guarantee payment to creditors and that, instead, it damages the economic cycle, as the state must assume the cost of incarcerating debtors.

The draft bill proposed replacing the prison sentence with financial and administrative restrictions that do not prevent the indebted person from working to repay the debt, or with other complementary penalties as provided for in the penal code, such as confiscation of assets. The draft also suggested the roll-out of electronic checks for transactions between individuals or merchants, to provide greater security and transparency, and called for judges to consider requests for parole from people imprisoned for issuing NSF checks.

Even the employers' organization, the Tunisian Confederation of Industry, Trade and Handicrafts (UTICA), long opposed to the decriminalization of NSF checks, has revised its position.

In 2011, the organization opposed any decriminalization, claiming that such a move would “make the check lose its value and importance as a means of payment.”[71] In November 2020, at a hearing before a committee of the ARP, and following the submission of a bill to decriminalize the issuing of NSF checks, UTICA leaders asserted that abolishing the prison sentence for this offence was “not a solution to combat this crime; on the contrary, it will exacerbate the economic crisis [...] and the crisis affecting small businesses and craftsmen.”[72]

However, when the organization was again asked in July 2023 by a commission of the new ARP,[73] UTICA president, Samir Majoul, stated that the employers' organization was now opposed to imprisonment for issuing NSF checks. He pointed out that prison sentences have proven to be unnecessary and were contrary to the principles of commerce. UTICA recommended the introduction of preventive mechanisms to avoid the non-payment of issued checks such as the introduction of electronic checks and capped checks, along with a modernization of the administration.[74]

For Jamel Ksibi, president of the Federation of Building and Public Works Contractors (Fédération des Entrepreneurs en BTP, in French), a member organization of UTICA, there was a dire need for alternatives to debt-imprisonment and banking sector reform.

“Banks sometimes give checkbooks to people who aren't financially solvent, so they withdraw their responsibility. The bank is only affected if a borrower doesn't pay his loan, but not if a check is rejected. Banks need to play their role as intermediaries,” he said. This could be achieved both by digitalizing the banking system to make operations more secure, and by improving access to bank loans, according to Ksibi.[75]

In France, the decriminalization of bounced checks under Law No. 91-1382 of December 30, 1991, on the security of checks and payment cards, [76] was heralded, two years after its implementation, as “an indisputable success (in relation to the legislator's objectives of reinforcing the security of check payments)” in an assessment by the Banque de France, the French central bank.[77]

The French law repealed the offense of issuing an NSF check, which is now essentially punishable by a banking ban, the implementation of which is entrusted to the banking system. It has also improved beneficiary protection by reinforcing the security of check transactions.

However, the following are still considered criminal offenses: “the withdrawal of funds after the check has been issued, with the intention of harming the rights of others; a stop-payment order not based on legal grounds, with the intention of harming the rights of others; the forgery and falsification of checks and payment cards; and the violation of a check-issuing ban.”[78]

In two years, the new law led to a 15.8 percent reduction in all irregular checks, and a 16.6 percent reduction in NSF checks alone. It also led to a drastic fall in the number of judicial banking bans (court-ordered bans), according to the same assessment by the Banque de France.[79]

Other countries, such as the eight countries of the West African Economic and Monetary Union (known by its French acronym, UEMOA), took steps to decriminalize bounced checks in 2011, at the initiative of the Central Bank of West African States, with a view to modernizing payment systems.[80] Mauritania, where the use of “guarantee checks” was commonplace, reformed its commercial code in January 2020, to modernize its commercial law, promote the protection of human rights, and improve the business climate, according to a report by the Mauritanian ministry of justice.[81]

Negative Consequences for Businesses

In addition to being ineffective in obtaining repayment from debtors, imprisonment for debt harms economic activity. It often leads to business closures and job losses, whether the entrepreneurs go to prison or go into hiding or exile.

Of the 12 people whose cases we followed, all have ceased their initial activity. Among their businesses, only the one belonging to Mejid Hedhli was still running some years after his arrest, as it has been handed over to one of his colleagues. All the other entrepreneurs are either out of business, working in informal day-to-day jobs, or in exile.

Although almost all the interviewees' businesses have ceased all activity, they have not been formally closed or dissolved in the case of registered businesses. In fact, closing down a business requires following particular administrative formalities with the authorities, as well as paying any outstanding fees due to the state such as taxes and social security contributions. Because of the potentially high cost of this process, most entrepreneurs who are already in financial difficulty and indebted via NSF checks do not follow through with the official closing of their business, even when they have ceased all activity. In so doing, they continue to accumulate costs related to their business’s registration that they will have to pay in the future.

Even if a company declares bankruptcy, checks issued during the course of business and rejected because of insufficient provision of funds, remain the criminal individual responsibility of the issuer. If they have already been rejected by the bank, they cannot be cancelled as part of bankruptcy proceedings.[82]

Among the people we interviewed, two had asked the bank for a loan or an overdraft arrangement to cover their debts from checks, but both were rejected because of an NSF check.

Although the use of checks is risky, they are an indispensable business tool for VSEs and SMEs in Tunisia. Barriers to accessing financing for VSEs and SMEs, notably the difficulty of accessing the banking sector, have contributed to the institutionalization of the use of checks as a means of creating liquidity and enabling economic players to borrow in the short to medium term.

For suppliers, the threat of imprisonment in case of non-payment makes it a more secure transactional tool than others, such as a bill of exchange, which is in limited use. A bill of exchange is a written commercial document sent by a supplier of goods or services to his customer for payment in accordance with the terms specified in the bill, i.e. the amount, due date, and recipient of payment. In the event of non-payment of the bill of exchange, civil proceedings may be instituted.

According to ANPME spokesman Houas, bills of exchange, which were more widely used as commercial instruments ten years ago, have lost their value compared with checks. He also noted that online and card payments are little-used among small and medium-size enterprises in Tunisia.[83]

According to figures from the Tunisian central bank, between May 2020 and October 2020, checks were by far the leading means of payment in terms of transaction volume and third in terms of number of transactions, after card payments and bank transfers.[84]

Strains on Courts and Prisons

In addition to being ineffective, the automatic criminalization of bounced checks is costly for the Tunisian state, not least because it imposes significant burdens on the judicial and prison systems.

The courts are overloaded with check cases, according to lawyers we interviewed.

According to the government, 11,265 cases were brought before the courts with regard to the 496 people imprisoned for unpaid checks, including those already convicted.[85]

In Tunisia, each court of first instance is supposed to have a single judge for checks. Some courts however, such as Tunis, have several, due to the large number of cases referred to the courts.

A report published on the decriminalization of issuing NSF checks in France two years after the 1991 reform indicates that one of its immediate effects was to alleviate court congestion, given the drastic fall in the number of judicial prohibitions (court-order prohibitions).[86]

In Tunisia, people imprisoned for bounced checks, like the rest of the detainee’s population, face poor conditions in overcrowded prisons. According to official figures, in September 2021, there were altogether 23,484 prisoners in Tunisia – exceeding the system's official capacity of 18,577 – 54.9 percent of whom were in preventive detention.

According to figures from the Tunisian ministry of justice dating from 2016, a prisoner costs the Tunisian state an average of 32 Tunisian dinars (US$10) a day, equivalent to approximately 11,680 Tunisian dinars (US$3,700) a year.

In a report released in April 2014, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights called on Tunisia to reduce overcrowding in the penal and judicial system, in particular, by developing legislation that guarantees a fair investigation and trial, and by decreasing the number of short-term prison sentences.[87]

V. International Legal Obligations

International human rights law unequivocally prohibits the deprivation of liberty for failure to fulfill a contractual obligation. According to article 11 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which Tunisia ratified in 1969, “No one shall be imprisoned merely on the ground of inability to fulfill a contractual obligation,” which includes prohibiting the deprivation of personal liberty either by a creditor or by the state for failure to pay a debt.[88] According to A Commentary on the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, the term ‘merely’ specifies that cases of fraud are excluded, and that protection of article 11 “does not apply to where a debtor had the financial means to fulfil a contractual obligation but refused to do so.”[89] Under article 4 of the ICCPR, countries may take, in emergency circumstances, measures derogating from certain of their obligations. However, article 11 is specifically excluded from any derogation.

Tunisia also has an obligation to ensure that residents can attain an adequate standard of living. Under article 11 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), “an adequate standard of living” for an individual and his or her family entails “adequate food, clothing and housing, and to the continuous improvement of living conditions.” While debt creation and enforcement does not directly contravene this obligation, evidence shows that debt imprisonment, including the risk of imprisonment for bounced checks and certain types of debt enforcement, have detrimental consequences for the ability of many borrowers to secure basic economic and social needs for themselves and their families, including food, shelter, and health care. [90] In fulfilling its obligation to protect and promote human rights, Tunisia should prevent and at a minimum mitigate practices, including in the commercial sector in the Tunisian case, that have such consequences and be vigilant to ensure that the state is not complicit in such practices through institutions such as the police and courts.

Acknowledgments

This report was researched and written by Salsabil Chellali, Tunisia director at Human Rights Watch. Eric Goldstein, deputy director in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) division, edited the report. Hanan Salah, associate director in the MENA division participated in the initial research and reviewed the report.

Sarah Saadoun, senior researcher and advocate on poverty and inequality in the Economic Justice and Rights (EJR) division provided specialist review. Senior legal advisor, Clive Baldwin, conducted legal review. Tom Porteous, deputy program director, conducted program review.

Charbel Salloum, senior officer in Human Rights Watch’s MENA division, and Travis Carr, digital publications officer at Human Rights Watch, helped prepare the report for publication.

We would like to express our gratitude to all those who spoke with us during this research despite the difficulties and sometimes risks, the relatives of indebted and imprisoned people, as well as indebted and prosecuted people living in hiding in Tunisia or in exile.

Human Rights Watch would like to thank the members of the ANPME, our partners, and in particular, Abderezzak Houas, who provided expert review of the research and connected Human Rights Watch with several interviewees.

We are grateful to all the experts whose input benefitted this research, including but not limited to lawyers Ali Hadj, Najet Dhaiba, and Hanen Lekhmiri, judge Abdessatar Khlifi, finance expert Abdelkader Boudrigua, researcher Hamza Meddeb, and businessman and member of UTICA Jamel Ksibi.