The aftermath of the quarter-century-long civil war, which ended in May 2009 with the government defeat of the separatist Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), continued to dominate events in 2010. As pressure mounted for an independent investigation into alleged laws of war violations, the government responded by threatening journalists and civil society activists, effectively curtailing public debate and establishing its own commission of inquiry with a severely limited mandate. When United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon established his own panel to advise him on accountability issues in Sri Lanka, the government refused to cooperate.

Sri Lanka held presidential and parliamentary elections in January and April respectively. President Mahinda Rajapaksa easily won re-election, and the ruling United People's Freedom Alliance party remained in power with a significant majority in parliament. Two weeks after the presidential election, the main opposition candidate, former army chief Sarath Fonseka, was arrested and in August found guilty before a court martial of engaging in political activity while still in uniform, and was stripped of his rank and pension. In a second court martial in September, he was found guilty of corrupt military supply deals and sentenced to 30 months imprisonment.

In September, at the Rajapaksa administration's urging, parliament passed the 18th amendment to the constitution, which removed restrictions on central government control over important independent bodies, such as the police, judiciary, electoral bodies, and national human rights commission. The amendment consolidated central government power, in particular executive power.

Accountability

Sri Lanka made no progress toward justice for the extensive laws of war violations committed by both sides during the long civil war, including the government's indiscriminate shelling of civilians and the LTTE's use of thousands of civilians as human shields in the final months of the conflict.

Senior government officials have repeatedly stated that no civilians were killed by Sri Lankan armed forces during the final months of the fighting, despite overwhelming evidence reported by Human Rights Watch and others that government forces frequently fired artillery into civilian areas, including the government-declared "no fire zone" and hospitals. When in late 2009, former commander Fonseka, then a presidential candidate, stated he was willing to testify about the conduct of the war, the defense secretary threatened to have him executed for treason.

Rajapaksa established the Lessons Learnt and Reconciliation Commission (LLRC) in May 2010. The LLRC's mandate, which focuses on the breakdown of the 2002 ceasefire between the government and the LTTE, does not explicitly require it to investigate alleged war crimes during the conflict, nor has the LLRC shown any apparent interest in investigating such allegations in its hearings to date.

Internally Displaced Persons

After illegally confining more than 280,000 civilians displaced by the war in military-controlled detention camps-euphemistically called "welfare centers"-the government released most of the detainees in 2010. Many of those who returned to their homes in the north and the east face serious livelihood and security issues. About 50,000 people remained in the camps, primarily families that could not return to their former homes.

Arbitrary Detention, Enforced Disappearances, and Torture

The government continues to detain without trial approximately 7,000 alleged LTTE combatants, in many cases citing vague and overbroad emergency laws. The detainees are denied access by the International Committee of the Red Cross, and little is known of camp conditions or their treatment. They typically have access to family members but not to legal counsel. While the government asserts that it has withdrawn some of its emergency regulations, the Prevention of Terrorism Act enables security forces to circumvent basic due process.

There were reports in 2010 of new enforced disappearances and abductions in the north and the east, some linked to political parties and others to criminal gangs. The government continues to restrict access to parts of the north, making it difficult to confirm these allegations. Witnesses testified before the LLRC that relatives last known to be in government custody at the end of the war were forcibly disappeared and were feared to be dead.

The emergency regulations, many of which are still in place, and the Prevention of Terrorism Act give police broad powers over suspects in custody. Sri Lanka has a long history of custodial abuse by the police forces, at times resulting in death. In a particularly shocking case in January, a video camera caught police officers brutally beating to death an escaped prisoner.

Attacks on Civil Society

Free expression remained under assault in 2010. Independent and opposition media came under increased pressure, particularly in the run-up to elections. Sri Lankan authorities detained and interrogated journalists, blocked access to news websites, and assaulted journalists covering opposition demonstrations.

News outlets associated with opposition parties came under the most vigorous and sustained attacks. The government particularly targeted Lanka-e-News, a news website published in English, Tamil, and Sinhalese, often aligned with the opposition party People's Liberation Front (JVP). A contributor to Lanka-e-News, Prageeth Ekneligoda, left his office on January 24 and has been missing ever since.

Lanka-e-News was one of six news websites blocked by the state-controlled Sri Lanka Telecom internet provider for several days starting on January 26, the day of the presidential election. Even after the elections commissioner ordered Sri Lanka Telecom to unblock the website, the editor of Lanka-e-News, Sandaruwan Senadheera, was subjected to threats and intimidation. Following several abduction attempts, Senadheera went into hiding.

The government also targeted another JVP-owned bi-weekly newspaper, Irida Lanka. On January 29, police questioned senior news editor Chandana Sirimalwatte and two editorial assistants about a recently published article. While police released the assistants after several hours, Sirimalwatte was held without charge for 18 days. The police also sealed the newspaper's offices until a court ordered them opened again.

Some 20 journalists, media workers, and civil society actors went into hiding in the days following the January election out of concern for their safety. At least four journalists left the country, adding to the several dozen who have fled in recent years.

Arrests and Harassment of Opposition Members and Supporters

The sudden emergence of Sarath Fonseka as a plausible political challenger to Rajapaksa in November 2009 galvanized the opposition, bringing together such disparate parties as the left-wing Sinhalese-nationalist JVP and the right-leaning United National Front (UNP). Even the Tamil National Alliance (TNA), previously sympathetic to LTTE goals, pledged its support to Fonseka. Although Rajapaksa won the election by a comfortable margin, his administration targeted Fonseka and his supporters in what seems to have been an effort to remove not only Fonseka, but any strong opposition voice, from the public arena.

A few weeks after the January elections the government raided opposition offices and arrested dozens of staff members, including Fonseka. Some were arrested when security forces surrounded the hotel where Fonseka's staff were staying on election night; another 13 staff members were arrested and accused of conspiring to stage a military coup.

Key International Actors

Mounting pressure from the United States, some European governments, and intergovernmental bodies contributed to the Sri Lankan government's decision to establish the LLRC in May. Other influential international actors, including India and Japan, adopted a "wait and see" approach, failing to insist on more serious justice efforts. A US State Department report issued in August acknowledged that the government had not taken effective steps toward accountability and noted the LLRC's shortcomings. In October Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International, and the International Crisis Group declined an invitation to testify before the LLRC, citing its limited mandate and lack of impartiality. Also in October, United Kingdom Prime Minister David Cameron stated in parliament that there was a need for an independent investigation into the conduct of the war, seemingly retreating from parliament's prior commendation of the LLRC.

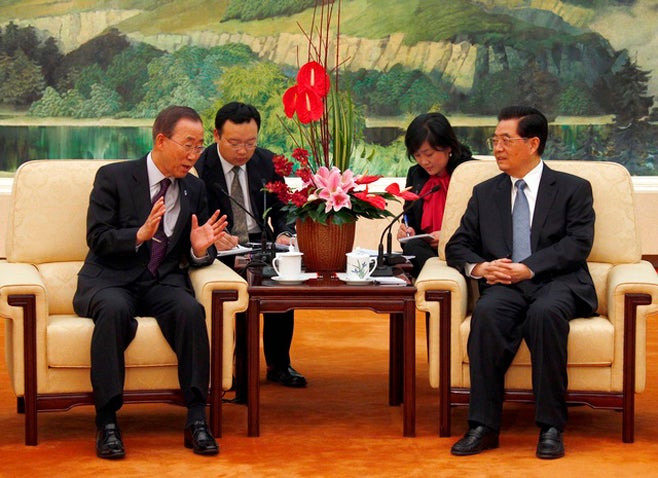

In June UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon established a three-member panel to advise him on accountability issues in Sri Lanka. The Sri Lankan government publicly castigated the newly created panel and, in early July, Housing Minister Wimal Weerawansa led a protest outside a UN office in Colombo, preventing staff from entering the building. It was only a few days later, after Ban recalled the UN resident coordinator to New York, that President Rajapaksa intervened and the protests stopped.

In June Japan announced that it would donate 100 million yen (US$1.23 million) through the UN High Commissioner for Refugees for humanitarian assistance to internally displaced persons in Sri Lanka. In July the European Union decided to withdraw Sri Lanka's preferential trade relations, known as the Generalised System of Preferences Plus, effective from mid-August, after it identified "significant shortcomings" regarding Sri Lanka's implementation of three UN human rights conventions. The government responded that the decision amounted to foreign interference and that Sri Lanka could manage without the trade benefits.

In September the International Monetary Fund announced that it had approved a US$2.6 billion loan to Sri Lanka following a two-week mission to the country.