The ruling by Britain’s highest court, the Law Lords, that the indefinite detention of foreign terrorism suspects is incompatible with the Human Rights Act and the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) is a profoundly significant decision, Human Rights Watch said today.

“This leaves the government’s strategy in tatters,” said Rachel Denber, acting executive director of Human Rights Watch’s Europe and Central Asia division. “The Law Lords have reminded us of a self-evident truth—that no threat, however real, can justify abandoning basic principles of liberty and justice.”

The appeal concerned government powers under section 23 of the Anti-Terrorism Crime and Security Act 2001 (ATCSA) to detain indefinitely without trial foreign nationals suspected of involvement in international terrorism. The U.K. parliament approved the law in the wake of the September 11 attacks. In October 2002, the Court of Appeal ruled that indefinite detention was compatible with the U.K.’s human rights obligations.

Indefinite detention is not allowed under human rights law. In an effort to comply with its human rights obligations, the government suspended (“derogated from”) part of its obligations under article 5 of the ECHR (the right to liberty).

The Judicial Committee of the House of Lords ruled by a majority of eight to one that indefinite detention discriminates on the grounds of nationality (article 14 of the ECHR), because it applies only to foreign nationals suspected of terrorism, despite a comparable threat from terrorism suspects with U.K. nationality. They also held that the suspension of human rights was unjustified because indefinite detention powers that apply only to some of those who pose a threat cannot be said to be “strictly required”—the legal test for suspending rights.

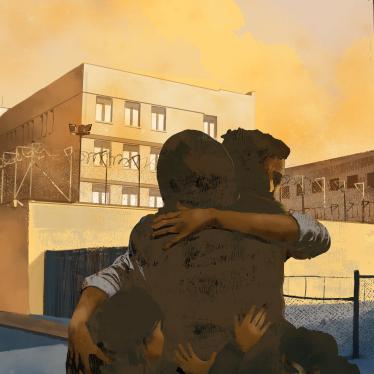

Eleven men are currently subject to indefinite detention without trial in maximum security prisons at Belmarsh and Woodhill, and Broadmoor high security psychiatric hospital. A twelfth man, known only as G, is on bail but effectively under house arrest. Seven of those in indefinite detention have been in custody for more than two years.

“The British government can no longer pretend that indefinite detention is compatible with its obligations under human rights law,” said Denber, “Those detained indefinitely at Belmarsh and elsewhere should now be tried in the criminal courts or released.”

The practical effect of the judgment is that the government order suspending part of article 5 of the European Convention has been quashed, and a “declaration of incompatibility” issued in relation to section 23 of the ATCSA. Under the terms of section 4 of the Human Rights Act, a declaration of incompatibility “does not affect the validity, continuing operation or enforcement” of any legislation. Parliament must now decide whether to repeal the provision. If it were to refuse to do so, the detained men could apply to the European Court of Human Rights.

The judgment of the Law Lords follows a growing chorus of U.K. and international criticism against indefinite detention, including by the Privy Counsellor Review Committee (“Newton Committee”) and Joint Human Rights Committee of the U.K. Parliament, the Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights, and most recently by the United Nations Committee against Torture.