(ニューヨーク)―香港政府当局は新しい国家安全維持法を急速に適用しており、平和的な言論の訴追、学問の自由の制限、根本的な自由への悪影響といった事態が広がりつつある、と本日ヒューマン・ライツ・ウォッチは述べた。2020年6月30日に中国中央政府が香港に導入を強いたこの法律は、1997年の主権移譲以来、香港市民に対する最も激しい攻撃だ。

香港国家安全維持法には、香港の人権保護に長期にわたる壊滅的影響を与えるであろう条項が含まれている。具体的には、特別な秘密治安機関の設置や公正な裁判を受ける権利の否定、警察への広範な権限付与、市民社会およびメディアの規制強化、司法による監視の弱体化などだ。

ヒューマン・ライツ・ウォッチの中国担当上級調査員マヤ・ワンは、「中国政府は一夜にして香港市民の人権を奪った」と述べる。「長きにわたって自由を享受してきた香港市民は、香港政府当局が嫌うバナーを携えていたり、スローガンを唱えただけで、長く服役するかもしれない事態に直面している。」

この1カ月間に香港警察は、民主派の抗議活動中に少なくとも4回、本法を適用した。香港返還記念日である7月1日恒例のデモ行進で10人、7月21日のデモ行進では1人が、香港の独立推進の目的ありと当局がみなした印刷物を所持・提示したとして逮捕された。

警察は今や、デモ行進の最中に国家安全維持法の旗を掲げて「旗およびバナーの掲揚」や「シュプレヒコール」で逮捕される可能性を参加者に警告している。7月2日、香港政府は2019年デモ行進のスローガン「光復香港、時代革命(香港を取り戻せ、時代の革命だ)」を違法であると通知。7月1日デモ行進の最中に、「香港を取り戻せ」と書かれた旗がついたオートバイで路上のあちこちにいた警官隊に突入していく姿が動画にとらえられていた男性1人が「転覆煽動」「テロリズム」で訴追されている。

香港国家安全維持法により、政治活動に携わる個人やグループは活動方法および場所の変更を余儀なくされている。中国政府が6月30日に法案を採択した数時間後、香港でもっとも著名な民主派政党の1つ「香港衆志(デモシスト)」が、同法への懸念を理由に解党し、 代表者の1人だった羅冠聰(ネイサン・ロー)氏が香港を離れた。若者たちが運営する2つの独立派団体「学生動源」および「香港ナショナルフロント」は香港においては解散したが、海外での活動は続けると述べている。予定されていた「民主派予備選挙」の数日前の7月9日に、香港基本法および本土関連業務の責任者エリック・ツァン氏が、投票を組織したり参加すれば、香港国家安全維持法に抵触する可能性があると警告した。この予備選は 9月に予定されている立法会(LegCo)選挙の立候補者を調整するために、香港の民主派政党が組織した非公式投票だ。

投票開始の前夜7月10日に、警察が学者のロバート・チャン氏率いる投票主催組織の事務所を「コンピューターの不正使用」の疑いで家宅捜査した。が、こうした威嚇にもかかわらず、61万の香港市民が7月11・12日の予備選で投票。その後、主催者だった區諾軒(アウ・ノックヒン)氏とアンドリュー・シュウ氏は、同法への懸念を理由に辞任した。

香港選挙管理委員会は7月26日と27日、立法会選挙に出馬する少なくとも16人の民主派候補者に詳細な質問状を送付。内容は、香港国家安全維持法に反対していたこと、香港政府と中央政府への「外国の力(foreign forces)」を模索しようとした疑惑について各候補者に問い、そのような活動は香港基本法と相入れず、不可分な中国の一部としての香港への忠誠に反するという見解を暗示するものだった。選管は2016年以降、独立派という政治的立場を理由に複数の候補者を失格処分にしているが、今回はその数がはるかに多くなるのではないかという懸念が深まっている。

ワン上級調査員は、「香港市民は、厳しい香港国家安全維持法にもかかわらず、発言をやめずに、驚くべき勇気を示し続けている」と指摘する。「香港政府当局は中央政府の支持を得て、長い間自由を享受してきた香港で、中国本土流の弾圧を行っている。」

香港国家安全維持法はまた、88万人超の学齢期の子どもたちの教育を受ける権利、情報・言論・表現の自由を規制している。香港教育局は7月3日、幼稚園を含むすべての学校に対し、香港国家安全維持法の教育を実施するよう求める通知を発行。今後速やかに、教師の研修を含む「サポート」を提供して、「国家安全維持の重要性」を生徒に確実に教えるとした。7月6日には各学校に対し、蔵書を再確認し同法に「抵触する可能性がある」書籍を処分するよう命じた。

7月8日、楊潤雄(ケビン・ヨング)教育局局長は、学校で「個人の政治的立場を表明するいかなる活動も行うべきではない」として、各校は非公式の抗議ソング「Glory to Hong Kong」の生徒による演奏を禁じるべきだと述べた。香港国家安全維持法の強制的な導入から1週間後、香港の大学HKU SPACEのプログラムディレクターが、「繊細な話題をめぐる議論」を回避するよう職員に警告する Eメールを送付。「政治的または個人的な見解を学校に持ち込むことにはゼロトレランス/絶対許されない」と通知した。

政治的検閲は、市民が情報に自由にアクセスする権利にまで及ぶ。香港公立図書館は7月4日、著名な香港民主派指導者らによる蔵書のうち少なくとも9冊の内容について、新法に沿うか確認する手続に付した。

また、香港国家安全維持法の萎縮効果はビジネス界にも及んでいる。これまでに殺害予告を受けていた民主派「経済サークル」への有名な参加者は6月30日、同法を理由に脱退すると発表した。筲箕湾地区にあるレストランには7月2日、「国家安全維持法に抵触するポスターやアイテム」の通報を受けて、警察が家宅捜査を行った。新法導入以来、これまで民主派運動への支持を表明していた12軒超の店舗が、関連ポスターを外した。市民が民主派ビジネスを見つけてひいきにできる複数のアプリも、デベロッパーによってアプリストアから削除されている。

香港国家安全維持法は金融サービス事業者に対し、同法違反の可能性がある顧客を当局に通知することを義務づけている。ロイター通信によると、HSBCやUBSを含む世界的な銀行が、顧客の民主派とのつながりについて精査しているという。両行とも具体的疑惑についてのコメントは拒否した。民主派の著名な指導者黄 之鋒(ジョシュア・ウォン)氏はフェイスブック上で、ある大手銀行が7月中旬、彼の口座に振り込まれた5桁の額の出所についてたずねる電話をしてきたことを公表した。同氏は、照会が彼自身の政治活動に関連するのか聞いたが、職員は回答を拒否したという。

ワン上級調査員は、「香港国家安全維持法は弾圧への道程そのものだ」と指摘する。「各国政府は国家安全維持法を公に非難すべきであり、香港市民に安全な避難場所をを提供し、同法の国外適用への協力を拒否しなければならない。」

新法の規定の詳細については下記よりご覧ください。

Roadmap for Repression: Hong Kong’s National Security Law

The National Security Law, imposed by the Chinese government on June 30 without consultation or legislative oversight, is a wide-ranging document that empowers Beijing to extend some of its most potent tools of social control from the mainland to Hong Kong.

The new law undermines Hong Kong’s rule of law and human rights guarantees enshrined in Hong Kong’s de facto constitution, the Basic Law. It contravenes the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which is incorporated into Hong Kong’s legal framework via the Basic Law and expressed in the Bill of Rights Ordinance. The covenant guarantees people’s rights to expression, information, association, and peaceful assembly, and rights to participate in public affairs, vote, and be a candidate for public office. It also ensures criminal suspects’ right to a fair and public hearing by an independent and impartial court.

Criminalization of Peaceful Speech, Activities

The National Security Law punishes four types of activities: secession (arts. 20-21), subversion (arts. 22-23), terrorism (arts. 24-28), and collusion with “foreign forces” (arts. 29-30), all carrying a maximum sentence of life in prison. Article 35 also states that anyone convicted of crimes under the law will be deprived of the right to run for public office for life.

The definitions of these crimes are overly broad and vague. “Subversion,” for example, criminalizes any act that seriously “interferes,” “disrupts,” or “undermines” the functioning of the Chinese or Hong Kong governments, a definition that can readily include peaceful protests. Both the crimes of “secession” and “subversion” make criminal acts that do not involve “force or threat of force,” meaning that peaceful actions, such as speeches advocating these ideas, can violate the law.

Mainland authorities have long used these vague crimes against people in China for promoting human rights. For example, the late Nobel Peace Prize winner Liu Xiaobo was sentenced to 11 years in prison for “inciting subversion” after he organized a joint letter calling for political reforms. The economist Ilham Tohti has been imprisoned for life for “separatism” because he spoke out for the equal treatment of ethnic Uyghurs.

Establishment of Specialized Secret Security Agencies

The National Security Law creates security agencies, including with Chinese mainland participation, that pose a direct threat to fundamental rights without accountability. The law establishes a central government-run security agency in Hong Kong, the Office for Safeguarding National Security (art. 48). The office, staffed by mainland security authorities, is to oversee and assist Hong Kong government agencies in “safeguarding national security” and to directly handle selected cases.

The composition of the office remains unclear. While the law states that the staff of the office “shall abide by the laws of” Hong Kong and China (art. 50), it also says that while on duty, these officers are outside the jurisdiction of the Hong Kong government and cannot be inspected or detained by Hong Kong law enforcement (art. 60). Human Rights Watch and others have long documented rights abuses committed by officers from mainland security agencies within China, including the use of intimidation, covert surveillance, enforced disappearances, arbitrary detention, and torture and deaths in custody of activists, rights lawyers, and journalists.

In addition, the new law establishes a Committee for Safeguarding National Security, which the Hong Kong chief executive chairs (art. 12). No individual or institution can “interfere” with the work of the committee, which is secret. Its decisions cannot be subjected to judicial review, the primary way that Hong Kong people have held government agencies accountable.

Criminal Suspects Deprived of Basic Rights

The National Security Law establishes a separate channel for those suspected of crimes under the new law for investigation, prosecution, and trial. It sets up a special department of the Hong Kong police tasked with investigating and handling political crimes (art. 16). Suspects can also be investigated by prosecutors and judges handpicked by the secretary for justice and chief executive, respectively (arts. 18, 44).

The law denies bail to national security suspects, unless the judge is convinced they no longer will commit national security offenses (art. 42). Defendants can also be deprived of a public trial if state secrets would be disclosed (art. 41), and of a jury trial if directed by the secretary for justice (art. 46). The government has released little information about the special police department, selected prosecutors, or judges.

In “complicated” and “serious” cases, mainland agencies, namely, the Office for Safeguarding National Security, and mainland Chinese prosecutors and judges can investigate and bring to trial suspects in political crimes, who are subjected to mainland criminal law (arts. 55-57). This suggests they could even be transferred to the mainland and further deprived of procedural protections that exist under Hong Kong’s legal system.

Hong Kong Police Given Sweeping New Powers

The National Security Law gives Hong Kong police sweeping new powers, many of which they can exercise without judicial or other forms of oversight. Article 43 and its Implementation Rules authorize police officers to conduct warrantless searches and covert surveillance, and to seize travel documents of those suspected of violating the security law. It also empowers them, without a warrant, to require internet-related companies to censor information, provide user identification information, and decrypt messages (Implementation Rules, sch. 4). In addition, the secretary for justice and the secretary for security can order the freezing of assets of those suspected of national security crimes (sch. 3).

Strengthened Control Over Civil Society, Media

The security law requires the Hong Kong government to “strengthen … supervision and regulation over … schools, universities, social organisations, the media, and the internet” (art. 9). Similarly, it also states that both the Office and the Committee for Safeguarding National Security will act to “strengthen the management” of foreign nongovernmental organizations and news agencies (art. 54).

The Implementation Rules for article 43 target, for the first time under Hong Kong law, “foreign agents” and “foreign political organizations” (sch. 5). The new law allows the police commissioner to demand information from individuals and groups deemed to fall within the definition of those terms, including personal information about an organization’s staff, and the organization’s activities, assets, and sources of income. Failure to provide such information can lead to a heavy fine and six months in prison.

The definitions of a “foreign agent” and “foreign political organization” are wide and vague – they encompass any organizations outside China that “pursue political ends” as well as people in Hong Kong funded by them – and put civil society organizations under greater scrutiny. In addition, the new law makes it a criminal offense to work with foreign entities to “impose sanctions” or engage in “hostile activities” against the Hong Kong or Chinese governments, wording broad enough to include advocacy activities independent groups regularly engage in (art. 29).

Many of these provisions could also be applied to journalists writing articles critical of the government. Article 29, for example, criminalizes providing “state secrets” – an undefined term – to any foreign individual or entity. That same article criminalizes those who “provoke … hatred” against the Chinese or Hong Kong governments. Mainland authorities have used these crimes against mainland journalists. Veteran journalist Gao Yu, for example, was detained for “illegally providing state secrets” after she shared a Chinese Communist Party internal censorship directive with foreign news agencies.

Removing Judicial Oversight

China’s legislative body, the National People’s Congress Standing Committee, has the power to interpret national laws. In Hong Kong, this has meant the Basic Law, which the Standing Committee has interpreted five times. The last time it did so was in 2016, to dictate the decision in an ongoing court case in Hong Kong involving two pro-independence members of the Legislative Council, leading to their disqualification from office.

In addition to the Basic Law, the National Security Law, as a national law, is also subject to interpretation by the Standing Committee. The new law further states that it supersedes all Hong Kong local laws, including the Bill of Rights Ordinance (art. 62). It is unclear, however, whether the security law supersedes the Basic Law as well, a question raised by the Hong Kong Bar Association, which the Hong Kong government has not clarified.

As a result, Hong Kong courts will have little ability to limit the reach of the security law when it conflicts with these laws, including those that guarantee human rights protections. Any judges who do so risk having the Standing Committee intervene to interpret the law. The new law, therefore, severely undermines the independence of Hong Kong’s judiciary.

Extra Territoriality

The National Security Law states that it applies beyond Hong Kong and China (arts. 37, 38). Under the law, anyone who criticizes the Hong Kong or Chinese governments anywhere in the world can potentially be charged with violating the security law, putting them at risk if they visit Hong Kong, or if their own governments agree to extradite them to Hong Kong.

|

報告書

中国:香港安全維持法は弾圧への道程

基本的自由にすでに悪影響

皆様のあたたかなご支援で、世界各地の人権を守る活動を続けることができます。

タグ

テーマ

人気の記事

-

2015年 6月 9日

バングラデシュ:児童婚で傷つけられた少女たち

-

2019年 3月 21日

ミャンマー:中国に「花嫁」として売られる成人女性・少女たち

-

2016年 9月 8日

ネパール:児童婚で脅かされる少女たちの未来

-

2021年 4月 19日

「血筋を絶やし、ルーツを絶やせ」

-

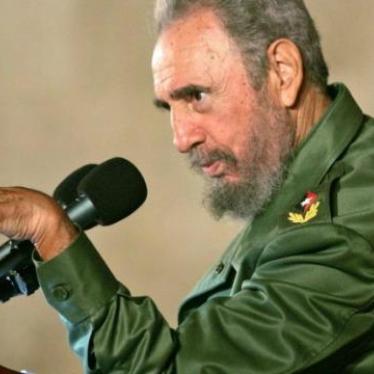

2016年 11月 26日

キューバ:フィデル・カストロ前議長 弾圧の歴史