Truth commissions and other mechanisms of transitional justice usually spring up in the aftermath of civil war or authoritarian rule. They do not thrive where the perpetrators still wield power or enjoy protection.

Little wonder then that the Middle East lags behind other areas of the world in reckoning with the past. The obvious exception is post-Saddam Iraq. A less-noticed exception is Morocco, where, in January, King Mohammed VI inaugurated the Equity and Reconciliation Commission to document abuses perpetrated under his late father, Hassan II, who ruled from 1961 to 1999.

The commission is tasked with investigating and documenting "grave" abuses that occurred from independence in 1956 until 1999. By April 2005, it is to provide both a general historical record of the repression and specific information to the families of several hundred "disappeared" Moroccans whose fate remains unknown. The commission is also to decide the level of compensation to pay to victims and their survivors.

It is no accident that Morocco is at the forefront of Arab countries in examining its repressive legacy. The country's openness toward its past - along with an outspoken press, a vibrant civil society, and recent reforms to the family code - helps burnish its image as one of the region's bright spots in terms of human rights. This is a valuable asset when, in terms of tackling poverty and unemployment, the government has achieved little. Addressing past violations is popular also with Morocco's political class, which includes many former political prisoners and torture victims.

The late king's ruthlessness toward his critics was not well known in the West, where he was admired as a "moderate," pro-Western ruler. From the 1960s to the 1980s, his security apparatus "disappeared" or imprisoned thousands of perceived leftists, Islamists, advocates of self-determination for the disputed Western Sahara, as well as real and imagined coup-plotters.

In the late 1980s, Hassan II began to ease the repression. The reforms he introduced over the next decade included a first stab at recognizing past abuses: In 1998, a human rights council he had established issued a report acknowledging 112 cases of disappearance.

King Mohammed VI has also recognized a duty to address the past. Soon after ascending the throne, he created a board that financially compensated some 4,000 victims of past abuses. But many victims and human rights activists criticized the compensation process, as well as the earlier acknowledgment of disappearances, as top-down efforts to turn the page without offering even a modicum of truth or accountability.

The new Equity and Reconciliation Commission meets these critics part way. Unlike the earlier bodies, the commission is mandated by its statute to establish a historical record that is to include "the responsibility of state or other apparatuses in the violations and the incidents under investigation." It is to compensate victims but also propose other remedies, including social assistance and rehabilitation, restitution of victims' bodies to their families, public memorials, and safeguards against a repeat of past practices.

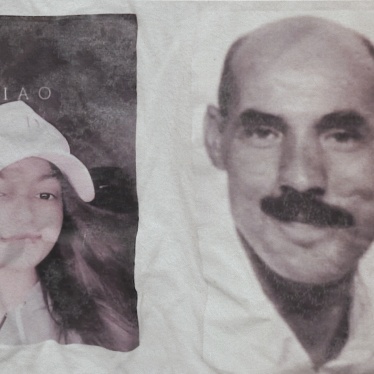

The mandate of the commission and its composition - the palace recruited the respected ex-political prisoner Driss Benzekri as president and several independent human rights activists as members - have convinced most Moroccan rights activists that they should engage with it. Their reservations, however, remain substantial.

First, the commission's statute explicitly bars it from determining individual responsibilities for abuses. (Note the absence of "justice" and "truth" in its name.) While information developed by the commission conceivably could be turned over to courts for possible action, this seems unlikely since Morocco's judiciary is hardly independent.

Second, the commission has no power to compel testimony or the production of documents. Its statute says that public institutions "must" cooperate with it. But without the stick of sanctions for non-cooperation or the carrot of an amnesty for those who come clean, which was the quid pro quo in South Africa's truth commission, how many policemen will tell what they know?

Third, the commission's mandate is to focus on cases of "arbitrary detention" and "enforced disappearance," but it is unclear whether the commission can document and provide compensation for other widespread violations such as torture, sham trials and the shooting of demonstrators.

Finally, the commission's credibility will hinge on how it confronts the present erosion of human rights. Last May 16, 12 suicide bombers killed themselves and 33 bystanders in coordinated attacks in Casablanca. In the past year, despite the near-complete absence of further acts of political violence, 2,112 Islamists have been charged, 903 convicted, and 17 sentenced to death, according to the justice minister. Human rights groups have documented that these suspects routinely were arrested without warrants, held in secret detention, sometimes tortured, and then convicted in unfair and hasty proceedings. The commission cannot simply ignore these abuses, which evoke the bad old days and reflect the continued power of a largely unaccountable security apparatus.

On Jan. 7, King Mohammed VI hailed the new commission as "the last step in a process leading to the definitive closure of a thorny issue." Yet each top-down effort in Morocco to deal "definitively" with past injustices has been superseded by a new "definitive" demarche. The commission, with its wider but still limited mandate, is likely to be one more marker in this journey. Nonetheless, it is part of a healthy process for Morocco, not least because it has been launched at a time when recent gains for human rights are at risk.

Eric Goldstein is research director for the Middle East and North Africa at Human Rights Watch.