Corrections: The following tweet in the piece below belongs to journalist Arash Karami:"The way Iranians are celebrating the open use of Facebook and Twitter from inside the country you’d think they just won World Cup."

The words "online party" in the following sentence were tweeted by journalist Golnaz Esfandiari: "Regardless of whether the free access to Twitter and Facebook resulted from a technical error or internal squabbling, the short-lived “online party,” as one journalist dubbed it, shows the overwhelming desire and expectation of Iranians for freedom of information."

In his first public speech after his June 14 electoral victory, President Hassan Rouhani remarked, “The government that takes its legitimacy from its people does not fear the free media.” For a few hours on September 16, Iranians wondered whether the government had lost its fear.

Iranian cyberspace was abuzz with excitement as Internet users gained open access to Twitter and Facebook. Users expressed shock and joy, some thanking Rouhani for stopping Iran’s censorship. An Iran analyst in the United States tweeted: “The way Iranians are celebrating the open use of Facebook and Twitter from inside the country you’d think they just won World Cup.” Thomas Erdbrink, the Tehran bureau chief for the New York Times, asked in a tweet if “Iran’s Berlin Wall of internet censorship [is] crumbling down?”

Others struck a more cautious tone, reminding users that people have gained temporary access to blocked sites in the past before again facing restrictions, and that the access may be associated with maintenance of the government’s filtering regime.

By the following morning many users in Iran were reporting blocked access to both Twitter and Facebook again. An official announced that a “technical glitch” had caused temporary access to some social media sites, but had since been “resolved.” He warned that authorities were investigating the matter and that “negligence” by Internet service providers under Iran’s cybercrimes law could lead to prosecution. Still, some questioned whether the temporary access had more to do with officials testing the waters, or perhaps even infighting between various governmental factions.

The authorities first blocked access to popular social media sites like Twitter and Facebook during the brutal government crackdown following the popular uprisings in 2009. Some analysts had nicknamed the uprisings, albeit prematurely, the “Twitter Revolution” because of the prominence of social media sites to link protesters with each other and the outside world. Since then, Iranians have had to access these sites through proxies or virtual private networks that allow them to circumvent filters. Even several high-ranking officials, such as Rouhani and Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, who have social media accounts linked to them, and Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif, who has a verified Twitter account, must use these roundabout methods of access.

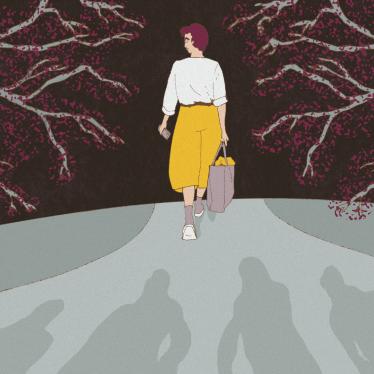

Regardless of whether the free access to Twitter and Facebook resulted from a technical error or internal squabbling, the short-lived “online party,” as one journalist dubbed it, shows the overwhelming desire and expectation of Iranians for freedom of information. For them, the glitch that needs to be “resolved” is not a few hours of open access to Twitter and Facebook, but the tight grip of censorship imposed by a government that fears its own people.