(Nairobi) – People with disabilities in the Central African Republic were often left behind and struggled to flee to safety when their communities came under the brutal attacks by armed groups beginning in 2013, Human Rights Watch said today. When they did reach sites for internally displaced people, they faced difficulties accessing sanitation, food, and medical assistance. Human Rights Watch released a new video in which people with disabilities described their struggles during the conflict.

The United Nations Security Council is expected to renew the UN peacekeeping mission in the Central African Republic on April 28, 2015. The mandate is expected to include for the first time a specific requirement to pay particular attention to the needs of people with disabilities, and to report and prevent abuses against them.

“One of the untold stories of the recent conflict in the Central African Republic is the isolation, abandonment, and neglect of people with disabilities,” said Kriti Sharma, disability rights researcher at Human Rights Watch. “The Security Council’s action will help ensure greater visibility to the needs of people with disabilities.”

Human Rights Watch briefed a number of Security Council members, UN agencies, and humanitarian organizations on our findings. One senior UN official familiar with the emergency response in Central African Republic told Human Rights Watch: “We don’t pay enough attention to the issue of disability. We should be doing more. There is no place for discrimination in humanitarian action.”

The Central African Republic has been in acute crisis since early 2013, when the mostly Muslim Seleka rebels seized power in a campaign characterized by widespread killing of civilians, burning and looting of homes, and other serious crimes. In mid-2013, groups calling themselves the anti-balaka organized to fight against the Seleka. The anti-balaka carried out large-scale reprisal attacks against Muslim civilians in Bangui, the capital, and western parts of the country. Thousands were killed and hundreds of thousands forcibly displaced during the conflict, including people with disabilities.

“During the war, people with disabilities lost everything; their wheelchairs, their homes, their livelihoods,” Simplice Lenguy, president of the group representing people with disabilities in the M’Poko camp for internally displaced people in Bangui, told Human Rights Watch. “Going back to our neighborhoods is going to be impossible without significant support from humanitarian organizations.”

“People with disabilities will need support to rebuild homes, get food and medical care, and create income-generating activities,” he said. People in the M’Poko camp were expected to begin leaving voluntarily as early as April 24. Aid and support services for people with disabilities will be especially important as the transitional government begins to close down displacement camps and help people to return home.

From January 13 to 20 and from April 2 to 14, Human Rights Watch interviewed 49 people in Bangui, Boyali, Yaloké, Bossemptélé, and Kaga Bandoro, including 30 with physical, sensory, psychosocial, or developmental disabilities; their families; government officials; diplomats; and representatives of aid agencies and local disabled persons organizations.

Human Rights Watch found that at least 96 people with disabilities had been abandoned or were unable to escape and that 11 were killed in Bangui, Boyali, Yaloké, and Bossemptélé. The figure is probably a fraction of the total. Most spent days or weeks, and in a few cases up to a month, in deserted neighborhoods or villages with little food or water. People with physical or sensory disabilities interviewed, especially those who were abandoned, were often unable to negotiate the unfamiliar and uneven terrain without assistance.

Hamamatou, a 13-year-old girl from the town of Guen in southwestern Central African Republic who had polio, told Human Rights Watch that her brother carried her on his back when their village was attacked until he got too tired to continue. “I told him, ‘Souleymane, put me down and save yourself,’” she said. “He said he would come back for me if they didn’t kill him.” He never came back.

When anti-balaka fighters found her two weeks later, Hamamatou described what happened: “The fighters said, ‘We have found an animal. Let’s finish it off.’” Another anti-balaka soldier intervened to save her life.

Father Bernard Kinvi, director of the Bossemptélé Catholic hospital, 300 kilometers northwest of Bangui, said that he and his fellow priests spent days looking for survivors following a massacre of some 80 people by the anti-balaka militia in January 2014, and that 17 out of the 50 people left behind in Bossemptélé were people with disabilities. Among them was an elderly blind woman who was left for dead and who spent five days lying in the riverbed among several corpses; a young boy with polio he found hiding five days after the massacre; and an elderly man who had lost his feet and hands to leprosy found abandoned in his home several days after the massacre.

The gravity of the crisis in the Central African Republic, coupled with the alarming number of humanitarian emergencies globally, has resulted in an overwhelming burden on aid agencies. Although the United Nations has categorized the situation in the Central African Republic as one of the gravest by its standards, the country has not received adequate humanitarian funding. According to the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA), since the beginning of 2015, the Central African Republic has received about US$126 million, less than 20 percent of the $613 million its strategic response plan calls for.

With limited aid available, aid agencies were often unable to address the specific challenges faced by people with disabilities. Of the eight UN and nongovernmental aid agencies Human Rights Watch interviewed, none were systematically collecting data on people with disabilities, and their needs were not fully included in the agencies’ programming.

The United Nations, nongovernmental aid agencies, and the transitional government should take into account the needs of people with disabilities in their response to the crisis and include people with disabilities themselves in their planning and decision-making processes, Human Rights Watch said. For this critical work to take place, it is essential for donors to invest in disability-inclusive humanitarian efforts.

Humanitarian agencies and the transitional government should begin to systematically collect data on people with disabilities to include them in policy decisions and assistance programs. People with disabilities should be included in the Bangui Forum, a national dialogue slated to take place from May 4-10. The government should also take steps to ensure that people with disabilities can fully participate in elections scheduled for August.

“People with disabilities are too often overlooked by aid groups and peacekeeping missions seeking to help the victims of conflict,” Sharma said. “The UN and aid agencies should train their staff to make sure people with disabilities have equal access to all services in the camps and in their communities as they return home.”

Fleeing Violence

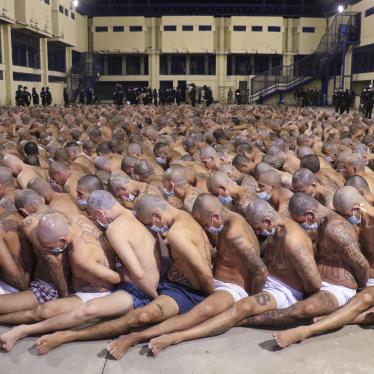

At the height of the conflict in early 2014, people with disabilities were neglected in the large- scale evacuation of tens of thousands of Muslims from the capital, Bangui, and towns and villages across western parts of the Central African Republic. The commercial trucks used to transport people to camps for internally displaced people or refugee camps in neighboring countries were high off the ground, making them extremely difficult to access for people with physical disabilities unless they had assistance. In the chaotic and desperate flight, there was often little or no help to board the trucks.

When more than 1,500 Muslim survivors fled the city of Bossemptélé in March and April 2014 in commercial trucks, Human Rights Watch found that at least 17 people with disabilities, mostly children who had survived polio, were left behind.

Those who managed to board were often unable to take their wheelchairs or other mobility devices since there was limited room in the vehicles and boarding was chaotic, with some only having minutes to climb on or risk being left behind.

A number of people with disabilities decided to stay behind rather than lose their wheelchairs. “How will people with disabilities move around without their tricycles once they reach the camps?” one disability rights advocate said. “They preferred to die with dignity and pride at home.”

Dieudonné Aghou, vice-president of the National Organization of the Association of Persons with Disabilities (Organisation Nationale des Associations des Personnes Handicapées, ONAPHA) told Human Rights Watch: “The Seleka would attack very suddenly, driving up at high speed in their 4x4 trucks, whoever couldn’t flee quickly was attacked. Even in the second phase, during the anti-balaka reprisal attacks, families fled leaving behind relatives with disabilities. In the list of victims, there are many people with disabilities, yet no credible organization is working on our needs in [this] conflict.”

Obstacles in fleeing

A key challenge in escaping was the absence of assistive devices such as wheelchairs, tricycles, or crutches, which were lost in the chaos, left behind, or looted. One man with a physical disability living in Bangui told Human Rights Watch: “People broke down the door, looted my home and took my wheelchair. If I could walk, I could have defended myself.” Another challenge was inaccessible terrain, especially in rural areas where the only safe place to hide was in the bush.

In Kaga Bandoro, Henry Gustave – a polio survivor who cannot walk – told Human Rights Watch how he fled after the Seleka and anti-balaka started fighting in town in 2014: “I used my tricycle to move fast and hide in the bush. With my family we fled into the bush and stayed there for two months.” However, they had to move after they were attacked again by ethnic Peuhl herders who sometimes ally themselves with the Seleka. “When we were attacked, I wanted to take the tricycle, but it was too heavy and cumbersome to move in the bush, so we had to abandon it. Since then my uncle went back to get it but only the frame is salvageable, the rest of it is destroyed.”

Many people with physical or sensory disabilities found the prospect of the journey too daunting so they decided to stay back. Jean-Richard, a man with a physical disability, told Human Rights Watch: “In my state I couldn’t leave [without assistance]. Everyone left but I stayed back and locked myself in the house. I stayed there for a week without any food.”

Some people with disabilities chose to stay in their homes, believing that because of their disability, attackers would spare their lives. But in some cases people with disabilities who were unable to flee were killed by the attackers. A blind man and another man with a physical disability were among 11 people killed in the November 2013 Seleka attack in Ouham-Bac in northwestern Central African Republic. Relatives who later found the blind man’s body told Human Rights Watch that it appeared he had been dragged from his hiding place and executed.

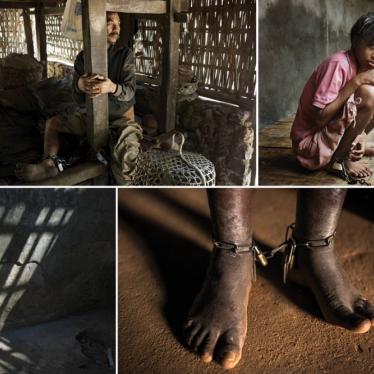

Abandonment

Families of people with disabilities are faced with a difficult choice during a conflict, Human Rights Watch found – often a split-second decision, either to flee and save themselves or to risk being killed to save a relative with a disability. As a result, people with physical or sensory disabilities were often left behind.

Human rights defenders and disability rights advocates told Human Rights Watch that, based on information they were able to collect in their own districts, they found 57 people with disabilities abandoned in homes in Bangui. The totals are probably higher.

Ambroise, a 27-year-old man with a physical disability from Bangui, described what happened on December 9 when the Seleka entered his neighborhood: “The Seleka came and started killing people. I was fast asleep when I heard gunshots and woke up to find myself alone at home. My parents had fled without me. I started shouting and crawled to the entrance of my house but when I looked outside, there was no one. I stayed alone for a day until a young boy passed by. I started crying when I saw him and begged him; ‘Please help me! If you leave me, I will die.’ The young boy feared for me and agreed to carry me on his back till the airport [the camp for displaced people].”

Lack of information or awareness

Since the attacks occurred without warning, people who are deaf or have a psychosocial or intellectual disabilities simply did not hear, know about, or understand what was happening. Human Rights Watch documented the case of a tailor in Bangui with a mental health condition who was shot and killed by the Seleka because he continued to work at his shop in the market while everyone else fled. One of his acquaintances said: “He just didn’t understand.”

The situation of people with psychosocial or intellectual disabilities has been particularly ignored, since even domestic disability rights organizations focus almost exclusively on people with physical disabilities and frequently don’t include people with psychosocial or intellectual disabilities in their work.

Life in Camps for Displaced People

Life in Bangui’s M’Poko camp for internally displaced people, adjacent to the airport, and in Muslim enclaves, such as the one in Yaloké, is difficult for all, but people with disabilities face additional challenges in meeting their basic needs such as food, sanitation, and health care. Similar problems are likely to be found in camps across the country as the number of internally displaced people soars in the central part of the country.

Local authorities and humanitarian agencies are not systematically collecting data on people with disabilities in either of the sites identified above. Local groups for people with disabilities have indentified 123 people with physical and sensory disabilities in the M’Poko camp. Given that there are 18,300 people in the camp, as of early April, and no data on people with psychosocial or intellectual disabilities, it is likely that this figure seriously underestimates the problem.

For people with physical or sensory disabilities, displacement camps can be hard to navigate. People with disabilities interviewed said that they were unable to make their way to food distribution sites as the location was not accessible or by the time they made their way to the site with assistance, the distribution was already over. Food distributions in M’Poko camp ended in the first half of 2014.

Following the government’s decision to return people from M’Poko camp in Bangui to their homes, aid organizations will facilitate their return with food rations for two months, and four months for the most vulnerable. They will also provide them with about 90,000 CFA (about US$150, which is the equivalent of rent for six months), plastic tarp, a hygiene kit for women, and three mosquito nets.

Once they are back in their neighborhoods, aid organizations will work with local authorities to ensure that families have access to services such as medical care and schools. It will be essential to fully include people with disabilities in these efforts.

Sanitation and health

The environment in the M’Poko camp in Bangui, as in other displacement sites, is inaccessible, with uneven surfaces and open sewage drains that make it difficult for people who use wheelchairs or who are blind to move around without assistance.

Accessing basic necessities such as latrines can be difficult as some are not fully accessible and often people with physical disabilities have to crawl on the ground to enter, exposing them to potential health risks. Jean, a man with a physical disability living in M’Poko camp, said: “My tricycle doesn’t fit inside the toilet so I have to get down on all fours and crawl. Initially I had gloves for my hands so I didn’t get any [feces] on them but now I have to use leaves.”

For people who are blind, moving around the camp without assistance can be extremely dangerous, as they can fall into filthy open sewage drains or burn themselves on open fires. Human Rights Watch heard of several cases in which blind people in the M’Poko camp had been burned by open fires or boiling water. Aimé, a blind resident of M’Poko camp and a popular musician, told Human Rights Watch, “Sometimes I become so angry and discouraged by the difficulties of living here that I just stay inside the whole day.”

Without mobility aids, many people with disabilities are forced to crawl on the ground to move around, and as a result, they are at great risk of life-threatening infections, such as respiratory problems related to inhaling excessive amounts of dust.

People with disabilities also face increased barriers in accessing basic medical care even when it is provided in the camp. This not only concerns people with physical disabilities who may be unable to go to the clinic but also extends to people with sensory disabilities.

The M’Poko camp medical clinic has no one to facilitate communication with deaf people. As a result, deaf people who cannot read or write and are not accompanied by a relative or friend who can assist with communication may hesitate to seek medical help or find it difficult to communicate if they do.

Gilbert Nguerepayo, a sign language interpreter who used to live in the Don Bosco camp in Bangui, told Human Rights Watch: “Humanitarian organizations do not pay enough attention to deaf people. Medical care is a real problem. There is no one to support them and they face difficulties in communicating.” At the request of deaf people, Nguerepayo often facilitated communication between them and doctors in his camp but deaf people in M’Poko had no such support, as there are no sign language interpreters in the camp. He is called in by the local disabled persons’ organization in M’Poko to provide sign language interpretation for events but not for individual cases. Nguerepayo is one of the few sign language interpreters in the entire country, and is largely self-taught.

In the Muslim enclave in Yaloké, access to medical care and nutrition has been poor, particularly for people with disabilities. Mamadou, a 14-year-old polio survivor, fled his home on the back of a donkey. Mamadou’s father told Human Rights Watch: “We had a donkey to carry Mamadou but it died on the way. We had to negotiate to buy another donkey but when we came across the anti-balaka, they stole the donkey from us. We didn’t know what to do so my wife and I would take turns carrying him. Mamadou was crying like it was never going to end.”

Due to the uneven and bumpy terrain, Mamadou fell a few times during the journey and sustained injuries that went untreated and prevent him from even supporting himself with a cane. “Before [the war] Mamadou was better; now he can’t even walk,” his father said. Once he reached the Yaloké enclave, his health deteriorated because, according to his family, he had to crawl on the ground and had little to eat. Although his family took him to the nearby clinic, only mild painkillers were available.

When Human Rights Watch interviewed Mamadou in January, he weighed less than 8 kilograms and according to the doctor at the Bossemptélé Catholic mission was suffering from an acute pulmonary infection due to the dust he inhaled crawling on the ground. The dire living conditions and lack of access to medical care has led to 53 people among the displaced community in the camp, including children and adults with disabilities, dying from malnutrition, respiratory illnesses, and other diseases.

According to the two leading medical assistance organizations, due to the scarcity of trained professionals, mental health care and support services for people with psychosocial disabilities are limited. In the areas that Human Rights Watch researched, there are no community-based mental health services available and only one hospital in Bangui provides a few psychiatric medications. Even prior to the conflict, there was an acute shortage of mental health services with only a handful of professionals and few services available; however the need for mental health care has increased. The conflict has traumatized a significant part of the population, leading to a likely increase in mental health conditions including post-traumatic stress disorder and depression.

In one case, a 17-year-old-boy with an intellectual and physical disability, Suleiman, was fleeing when he saw his uncle being brutally killed. Suleiman appeared to be traumatized by what he saw but has never received any counseling or psychosocial support. He told Human Rights Watch: “My uncle’s death in front of my eyes continues to scare me…When I sleep, I have nightmares that bring back the images of the events I lived. I haven’t spoken to anyone about it.” While one medical nongovernmental group is considering providing mental health support for victims of gender-based violence, these services would not help others with mental health problems.

Access to food

In displacement sites of M’Poko, Yaloké, and Kaga Bandoro, people with disabilities, especially those without families, are often unable to obtain food during distributions as they typically find out too late or are unable to go because the location is inaccessible. People with disabilities living in the M’Poko camp organized a system of food distribution among themselves where a few camp leaders would collect food during distributions and then hand it out to all people with disabilities who were unable to access the distribution site. However, the transitional government’s decision to end food distributions has proved extremely difficult for people with disabilities, especially those with no family support, and contributes to malnutrition.

Rodrigue, a young man with a physical disability who lives alone in M’Poko, has to pay someone every day to take him in a cart outside the camp, where he sits all day in the sun to beg for money for food. Once back in the camp, he is dependent on the availability and good will of his neighbors to cook food for him and bring him water.

Once the M’Poko camp shuts down and people return home, people with disabilities like Rodrigue, are likely to continue to have difficulty in getting food and meeting other basic needs. After the food provided by aid groups to returning families runs out, families will have to supply their own food. For people with disabilities, especially those who were abandoned by their families, this may prove particularly difficult.

For some people with disabilities living in Yaloké and Kaga Bandoro, even being able to benefit from food distributions is difficult. Noel’s right hand was amputated in 2014 after he was shot by Seleka fighters outside of Kaga Bandoro. “There is not enough to eat and when we are receiving assistance I don’t have the strength to – and can’t carry – my goods,” he said.

Access to education

Human Rights Watch found that very few children with disabilities are enrolled in schools in camps like M’Poko. The school in the M’Poko camp has over 3,797 children enrolled; of whom only 14 have disabilities. While the school is wheelchair-accessible, the route to the school is not. Children with physical disabilities cannot attend unless a family member takes them there and picks them up, and they have an assistive device. Without an assistive device, such as a wheelchair, children with physical disabilities can find it hard to sit all day on the floor.

The school’s staff told Human Rights Watch that some parents are hesitant to send their children with physical disabilities to the school as they fear that in case of an attack the children will not be able to flee. Children with sensory or intellectual disabilities are unable to attend the school because the school does not have teachers trained in inclusive methods.

“None of our staff is trained to teach children who are blind, deaf, or have other disabilities,” said a staff member working at the school. “So it serves no purpose to let children with disabilities come to this school.” The school staff has encouraged parents to enroll their children, but has not actively sought to enroll children with disabilities.