DHAKA—Sanjita had very little to say on the subject of how she felt about getting married. Maybe that’s because she’s 10 years old. She had married 18 days earlier, to a boy who is 14 or 15 years old—he works in a garment factory in Dhaka and as a rickshaw driver.

Her mother Mariam (this and Sanjita’s name are pseudonyms) had quite a bit to say:

I don’t have any sons who look after my husband and I. We’re getting old and fall sick all the time. My husband says ‘I can die anytime—before I die I want to make sure I carry out my duty to my daughter.’

It’s illegal in Bangladesh for girls to marry before the age of 18, and parents and others who arrange such marriages can face criminal penalties, but Mariam told me, “We’re not very educated so we don’t understand those laws.”

It’s not surprising that Sanjita’s parents don’t understand the law well—it’s almost entirely unenforced. After interviewing dozens of married girls, many of them married at ages as young as 10, 11 or 12, their families and community leaders in regions across Bangladesh, I couldn’t find a single case of someone being arrested for arranging the marriage of a child. Human Rights Watch’s research found that some local government officials try to enforce the law, but others supplement their salaries by selling forged birth certificates that allow child marriages to go ahead.

That helps to explain why in Bangladesh 29% of girls marry before age 15—the highest rate in the world. By age 18, when they should be graduating from high school, 65% of Bangladeshi girls are married.

Several girls in different parts of the country used exactly the same words in talking about the impact child marriage has had on their lives—“My life is destroyed."

Our research in Bangladesh and testimonies from child brides around the world confirm the terrible consequences of child marriage. The girls I interviewed had usually become pregnant early, either because they were pressured to or felt that they should, or because they had no access to contraception and information about family planning. Pregnancy in girls carries the risk of serious health consequences, including death as a result of complications. The children of these girls are also at heightened risk of health problems and early death.

Girls who stay in school are both less likely to become pregnant and more likely to have safe pregnancies; UNESCO data estimates globally that if all women completed primary education the maternal mortality rate could be reduced by 66%, from 210 deaths per 100,000 live births to 71.

The girls we interviewed had almost always left education permanently. Even if they left their husbands or got divorced early, economic and social pressures often kept them from resuming their studies. Although primary education is “free” in Bangladesh, meaning there are no fees, the reality is that associated costs for exam fees, stationary, pens, uniforms, transportation, etcetera put education out of reach for many girls even at the primary level, and many more are forced to leave when confronted with the higher costs of secondary education.

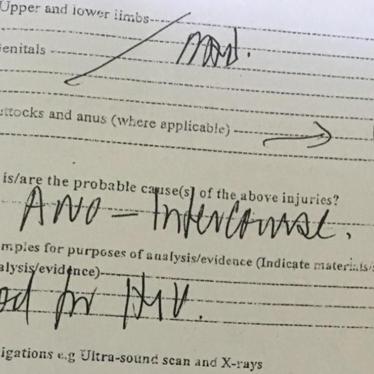

Many of the married girls we interviewed had suffered abuse from their husbands and in-laws, including rape and other physical violence including attempted murder. Some of the most heart-breaking stories were from girls who had been abandoned or cast out by abusive husbands and in-laws, yet had begged to be taken back, for lack of other options.

So how can parents be so cruel? The answer is that they are not, that often parents are faced with an impossible choice and doing what they think is best for their daughter. In too many families, there simply wasn’t enough to eat—or enough money to pay for children to go to school. Parents sometimes looked for a husband in hopes that that would allow their daughter to eat—or they sought to shield their daughter from sexual harassment or threats of kidnapping which they were powerless to prevent.

And there is another danger coming from an unexpected quarter. Bangladesh is one of the countries most affected by natural disasters, and it is also on the front line of climate change. Some families I interviewed were losing their homes and land to river erosion; others lose crops every year to flooding or had lost everything in a cyclone. These natural disasters encourage child marriage, especially for families watching their land erode, who rush to marry off their daughters before they are displaced.

Solutions will be hard in a country as poor as Bangladesh, but they are not impossible. Bangladesh has, in other development areas including reducing poverty and maternal mortality, had significant achievements. The prime minister, Sheikh Hasina, at the July 2014 Girl Summit in London, pledged to end child marriage under age 15, and reduce the frequency of marriage between ages 15 and 18 by one-third in Bangladesh by 2021. She also promised to end all child marriage under age 18 by 2041 and outlined steps to achieve these goals including reforming the law and developing a national plan of action. Although these goals, even if achieved, would see children continue to marry for the next 26 years, at least they seemed to signal welcome attention to the issue by the Bangladesh government.

It is easy to see what the plan of action should include. Make local officials enforce the law. Fire and prosecute officials who forge birth certificates. Try harder to keep girls in school, especially at the critical transition from primary to secondary school. Teach girls—and boys—about sexuality and family planning and the risks of early pregnancy. Crack down on sexual harassment and threats to girls. Do a better job of assisting families reeling from natural disaster.

In the months since the prime minister’s July 2014 speech in London, however, the government has failed to meet its own deadlines for law reform and planning. Worse yet, it has taken a step backwards by proposing to lower the age of marriage for girls from 18 to 16.

Bangladesh’s girls need their government to take them seriously—before another generation of girls see their lives destroyed.