The report is based on more than 90 in-depth interviews with patients, their families, healthcare professionals, government officials, patients’ advocacy groups, and other organizations conducted in Yerevan, the capital, and eight other towns and cities.

“The pains are unbearable,” Gayane G., a 46-year-old cancer patient told Human Rights Watch. “I cry, scream, feel like I’m walking on fire all the time. I try to endure the pain when someone is at home, but when I am alone, all I can do is cry.”

About 8,000 people die from cancer in Armenia every year, many of them in excruciating pain. Morphine, a key medication for treating severe cancer pain, is inexpensive and easy to administer, but widely inaccessible to people who need it. From 2010 to 2012 Armenia consumed an average of 1.1 kilograms of morphine per year, enough to treat about 3 percent of those estimated to need it. Other services that help people ease end-of-life pain and suffering are also largely unavailable.

Human Rights Watch identified the following obstacles to effective pain treatment in Armenia:

- Lack of oral morphine: Oral morphine, the medicine of choice for the treatment of severe chronic pain, is unavailable in Armenia.

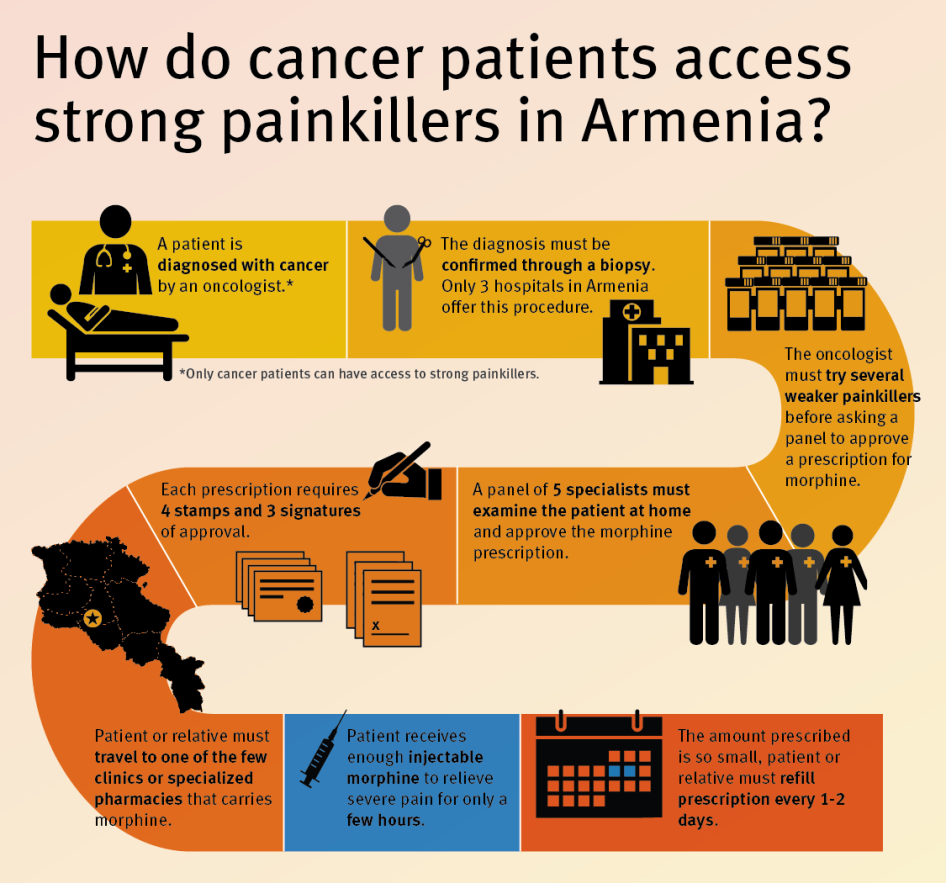

- Restrictive laws: The procedure for prescribing injectable opioids is complex, time-consuming, and involves significant bureaucracy. Only oncologists may prescribe opioids to outpatients, and only to cancer patients. Oncologists can prescribe opioids only after multiple doctors have visited the patient at home and signed off on the decision; multiple signatures and seals are necessary for each prescription.

- Inadequate dosage: Although Armenian regulations do not establish maximum dosages, the standard practice is to start a patient on a single opioids injection per day and then add a second daily injection after about two weeks. The pain-killing effect of injectable morphine lasts four to six hours, leaving the patient without adequate pain relief for most of the day.

- Onerous filling procedures: After opioid analgesics are prescribed, cancer patients or their caregivers must collect the prescription at their local polyclinic, fill it at large regional medical centers or, in Yerevan, at the only pharmacy that carries it, and return the empty ampoules before a new prescription is issued. They must repeat the process every other day or in some cases every day because in practice doctors will prescribe only enough strong opioids to last 24 or 48 hours.

- Tight police control: All oncologists interviewed for this report said that they provide written monthly reports to the police with details on the identity and diagnosis of patients who receive opioid painkillers, in violation of patient confidentiality rights.

Medical and nursing students receive virtually no training on palliative care and adequate pain treatment, and healthcare workers lack awareness, training, and guidance on medical use of opioid painkillers.

The severe obstacles to good palliative care in Armenia deny patients adequate medical treatment, and violate the right to health, Human Rights Watch said. Armenia’s lack of action to improve access to essential pain medicines may also violate its obligation to protect patients from cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment.

The government of Armenia has recognized the need for palliative care and taken some important steps in recent years to develop it. It has included palliative care in the government’s list of recognized medical services, established a palliative care working group, and, in close cooperation with experts and nongovernmental groups, developed a national strategy for implementing palliative care. Between 2011 and 2013, the authorities ran four palliative care pilot projects.

“The Armenian government has taken some important preparatory steps, but now needs to turn words into action,” Gogia said. “As a first step, Armenia’s government should reform its restrictive drug regulations and introduce oral morphine to alleviate the suffering of thousands of patients.”

Selected Quotes From Patients

“I felt like I was walking on needles. The pain would start from my hip and extend down to the entire right leg. I felt really bad, crying all the time. I did not know what sleep was during those pains. All I could dream of was a time when the pain would disappear, so that I would feel free. I felt so bad that I wanted to die....”

– Karine K., former kindergarten teacher, describing pain from abdominal tumor

“Pain attacks start unexpectedly and I start screaming and become a different person. When my hand starts burning like I hold it over a fire, I know the pain attack is about to start. When it starts I lose verbal communication skill and can only point to things with my right hand. I have the pain attacks every night, but sometimes it happens also during the day....”

– Lyudmila L., 61, retired kindergarten teacher, describing the pain from her inoperable breast cancer