(Tokyo) – The Japanese government has failed to protect lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) students from school bullying, Human Rights Watch said in a report released today. Japan has a bullying prevention policy, which is up for review in 2016 amid a growing national debate on equal rights for LGBT people.

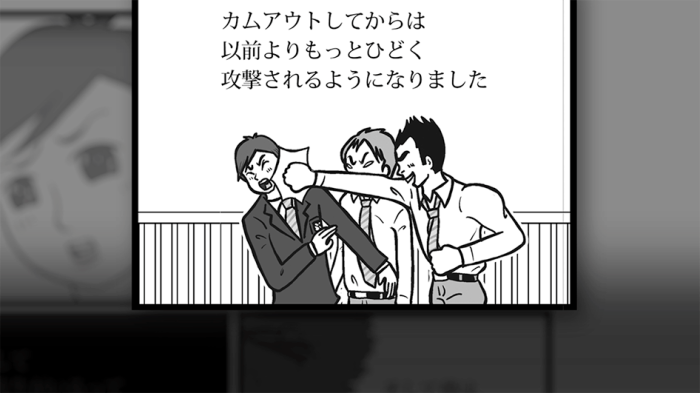

The 84-page report, “‘The Nail That Sticks Out Gets Hammered Down’: LGBT Bullying and Exclusion in Japanese Schools,” examines the shortcomings in Japanese government policies that expose LGBT students to bullying and inhibit access to information and self-expression. Bullying is widespread and brutal in Japan’s schools, yet government policies addressing bullying do not specifically address LGBT students, who are among the most vulnerable to bullying. Instead, the national bullying prevention policy promotes social norms at the expense of basic rights. LGBT students told Human Rights Watch that teachers have told them that by being openly gay or transgender, they are being selfish and should expect not to succeed in school.

Human Rights Watch conducted in-depth interviews with dozens of LGBT students, plus young adults who were recently enrolled in various types of schools, in 14 prefectures in Japan. Those interviewed were identified by counselors, peers, or through a survey distributed on Facebook and Twitter. Human Rights Watch also interviewed social scientists, psychiatrists, lawyers, government officials, and education policy experts. The report features four cases illustrated in manga cartoons – a common source of LGBT role models and information for Japanese youth.

In recent years, Japan’s Education Ministry has issued guidelines related to LGBT students, sending an important message that schools should care for sexual- and gender-minority children. However, the national bullying prevention policy is silent on the specific vulnerabilities of LGBT students – a gap compounded by the lack of binding policies on LGBT-inclusive curricula and inadequate teacher training on gender and sexuality. A law that requires transgender people to obtain a diagnosis of “Gender Identity Disorder” as a step toward gaining legal recognition can have a harsh impact on youth.

Bullying generally is a notorious problem in Japan. Students often target other students they perceive as different with harassment, threats, and sometimes violence – including by singling out students on the basis of their real or perceived sexual orientation or gender identity, Human Rights Watch said. However, while bullying has received media attention – especially in cases that resulted in death – and been publicly debated for decades, the Japanese government has failed to address its root causes, including the vulnerabilities of LGBT students. Instead, the government has promoted social norms and a climate of harmony in schools, and officials insist that no child is any more vulnerable to bullying than another. In meetings with Human Rights Watch, for example, officials in the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology repeatedly stated that they took a “holistic” approach to bullying and suggested that specifically addressing the needs of LGBT and other groups of students would afford special treatment to those students.

Nevertheless, Japan’s Basic Policy on the Prevention of Bullying, issued in October 2013, by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology, has proved to be inadequate. The policy emphasizes student education on social norms and teacher awareness-raising over children’s rights and mandatory teacher training. LGBT students are not mentioned anywhere in the policy.

Human Rights Watch found that LGBT students who attempt to report cases of bullying to their teachers receive a wide range of responses. Because there is no comprehensive, mandatory training on gender and sexuality for teachers, each teacher’s response to an LGBT bullying case depends on their individual opinions of LGBT people. Some students reported that their teachers told them to avoid future bullying by conforming to social norms. Others said they would never report a case of homophobic bullying because they had heard their teachers make anti-LGBT jokes and slurs.

Kiyoko N., a lesbian student in Tokyo, told Human Rights Watch her junior high school classmates would accuse her of not being “girly enough,” then swarm around her and beat her with a roll of paper. Her teachers witnessed the abuse again and again but did nothing. “It was common knowledge that I was being bullied,” she said. “It was also common knowledge that my teachers would never help me.”

17-year-old Tadashi I., a student in Nagoya, told Human Rights Watch: “I think if I tried to tell my teachers about the bullying they might try to solve the problem, but they wouldn’t know what to do because they know so little about LGBT people. They would make mistakes because of this, and it could get worse.”

Ai K., a former elementary school teacher who now works as a counselor for LGBT youth, said: “Even if one teacher is ready to help, the administration is likely not prepared to support that teacher, which can mean the teacher is left alienated in their own compassion.”

For transgender students in Japan, simply attending school can be an ordeal. National law mandates people to obtain a mental disorder diagnosis and other medical procedures, including sterilization, to be legally recognized according to their gender identity – an abusive and outdated procedure. While the government has stated in recent years that schools may accommodate transgender students without such a diagnosis, Human Rights Watch found that implementation of that recommendation is piecemeal. Transgender students are sometimes forced to wear school uniforms that do not correspond with their gender identity, denied access to bathrooms for their appropriate gender, and slotted into gender-segregated activities where they are not comfortable.

The Education Ministry has recently released a “Guidebook for Teachers Regarding Careful Response to Students related to Gender Identity Disorder as well as Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity,” a promising step because it signals that schools should be safe for all students, Human Rights Watch said. The guidelines, however, are non-binding and should be strengthened to explicitly specify, among other things, that transgender students do not need to obtain a diagnosis to access education based on to their gender identity.

The current momentum in the national political discussion on LGBT issues is promising, Human Rights Watch said. The government should take this opportunity to ensure that the needs of LGBT youth are included in the policymaking process and that all students in Japan can access education on an equal footing.

“No child’s safety or healthy development should depend on a chance encounter with a compassionate adult,” Doi said. “The government has a responsibility to train teachers to react to cases of bullying on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity, and to protect LGBT students from harassment and discrimination.”