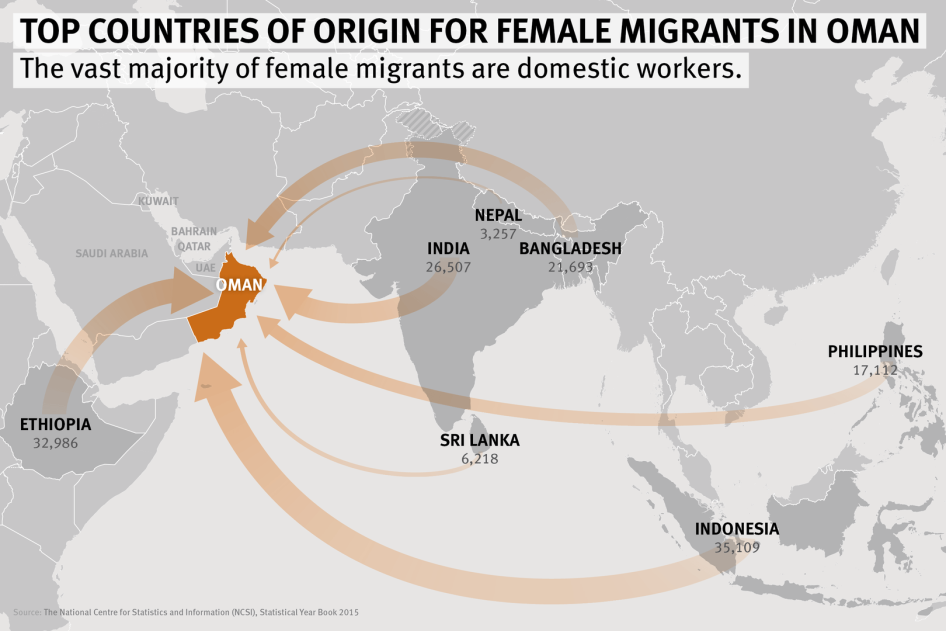

More than 130,000 women have left their home countries to work in Oman as migrant domestic workers, cooking, cleaning and caring for children while living in their employers’ homes. But behind closed doors, many of these women are beaten, starved, and forced to work up to 21 hours in a day. Rothna Begum speaks to Stephanie Hancock about her report, “I Was Sold,” and about the horrors taking place in this quiet, beautiful country that has, until now, escaped scrutiny on this issue.

Is it common for families in Oman to have domestic workers in the home?

According to official Omani data, about a quarter of Omani families have a domestic worker, but this figure could be far higher as lots of people hire undocumented workers.

Does Oman also operate a kafala system like other Gulf states?

Yes. This ties migrant workers’ visas to their employer, who is their sponsor. Workers cannot change jobs or employers without the permission of their sponsor. If a worker is threatened, beaten or even starved and flees her employer, she can be charged with “absconding” for leaving her job and faces imprisonment, a fine, and deportation.

This is a problem across the Gulf region, isn’t it?

Yes, employers in the Gulf know their workers can’t leave without fear of arrest. In many countries, including Oman, they are often not even called workers by employers and recruiters. Often they are referred to as ‘servants.’ We found that some employers behave as though they are entitled to delay or even withhold payment entirely as they see fit, for whatever reason.

So migrant domestic workers in Oman are not paid properly?

No, many are not. Many women told us they are not being paid their full salaries, or not being paid for months at a time, and sometimes not even being paid at all. Some employers not only confiscate passports but also withhold workers’ wages supposedly to stop them from running away. As many of these women decided to work abroad to support their families back home, this is devastating.

Are domestic workers in Oman physically abused?

We found some women who said they were physically abused. I met women who told me they were beaten with sticks, punched, slapped, kicked, and even burned with hot water or food. One Indonesian woman ran away after being beaten but the police caught her and returned her to her employer. They were so angry she’d run away that her male employer punched her in the face and broke her two front teeth.

What about sexual assault?

Sadly, that sometimes happens too. One woman said she was raped by her employer’s 27-year-old son. Another woman said she was sexually harassed by three adult sons in the family. Eventually she told their mother, “Your sons won’t leave me alone at night,” and begged to be allowed to leave. The mother relented and let her leave, but the new employer was also abusive and threatened to kill her.

How common is this kind of abuse?

Many domestic workers have good employers with good working conditions and decent salaries. But many others are not so lucky and find themselves trapped. It’s impossible to know how prevalent mistreatment is, but we found common patterns of abuse. For example, almost all the women we spoke to – even those who said they had good employers – said their employers confiscated their passports.

Many domestic workers in Oman live in rural areas, not towns. How does that affect them?

In some areas, families have land and animals that need tending to. So as well as cooking, cleaning, and looking after babies through the night, some of them also have to feed sheep and deal with manure. One young worker, “Babli,” had to water her employers’ 16 mango trees every day. But soon the family’s water bill went up a lot, and her employer beat her for wasting money. Sometimes mangos would fall off the trees, and the family even counted the fallen mangos to make sure Babli didn’t eat any of them.

Many women run away with no money, often with just the clothes on their back –not even a bottle of water. Even women who live in or near large cities often have to walk for miles in incredible heat to seek help. Those who live in very isolated areas far from the capital face even greater obstacles, and may flee even though they have no obvious way to reach their embassies or any other source of shelter or assistance. But some women genuinely fear they are going to be killed by their employer, and feel that they have no choice but to try.

What happens to those who escape?

Often, women who went to the police said they were discouraged from filing a formal complaint and sent back to their employers. Sometimes, police officers just called the family to come and collect their worker. They don’t write up testimony in a police report or call the family to investigate. One woman, “Mamata,” said she begged not to be sent back to her sponsor after she went to the police for help. But they ignored her. Mamata told us her employer beat her “mercilessly” when she arrived back at her employer’s home.

Can’t recruitment agents help these women?

Many women think the agent who recruited them from their home country is on their side. But agents have no financial incentive to help women leave their jobs, as they may have to return the fee they received for that worker. In one case, a woman who fled her employer was sent by police to the agency that recruited her. The agent, who may have had to pay back fees to her employer, told her: “I paid 200 rials (US$520)! If you pay this, then you can go.” But she had no money, so he then locked her in a room and beat her. She escaped shortly after by jumping out of a second-story window, and eventually made it to the airport, despite having cuts all over her feet.

Do any cases of worker abuse ever make it to court?

Rarely. In fact, some embassy officials from countries of origin in Oman told me that they have little faith in the justice system -- such that one official said that his embassy actually advises their citizens not to pursue cases. If you do want to take your employer to court, the cases can drag on for years and women are not allowed to work for anyone else in the meantime, so it’s a very costly decision with no guarantee of justice. The woman whose employer beat her up and broke her teeth did pursue her case, but after a year when she sat in a shelter with no income, her employer was acquitted and she went home without justice.

Is it true that workers’ wages are linked to nationality in Oman?

Yes. Most countries where domestic workers come from have set minimum salaries for their citizens as a protection measure. For Filipinos it’s $400 a month, $220 for Sri Lankans, $180 for Tanzanians, and so on. So employers can develop stereotypes of workers, like thinking they can hire a Filipino for $400 a month because they think she can speak English, or they’ll hire an Ethiopian who’s cheaper, as they think she is more submissive and they can make her work longer hours. Also, because Oman has no minimum wage for foreign workers, there may be no consequences if employers only pay women half of what they promised. And because of the kafala system, they know the worker is trapped and can’t leave them to work for someone who provides a higher salary without their permission.

Many Gulf states have the abusive kafala system. Are things worse in Oman compared to other Gulf states?

Until now, Oman has largely escaped scrutiny on this issue. But from what we found out about police attitudes and the justice system there, it appears as bad as in any neighboring country and, possibly worse than some of its neighbors. For instance, women I spoke to in the UAE had both good and bad things to say about the justice system. Some said the police tried to help or encouraged them to file a criminal complaint, and others felt the immigration department listened to them. I did not hear positive stories of the police or the dispute resolution mechanism in Oman. That’s very damning.

Why should Oman change if other countries – like Saudi and the UAE – refuse to?

Oman is a very hospitable country, and is known as being more tolerant and open than others in the region. It’s true Oman has a history of slave trade; centuries ago, it brought slaves over from the east coast of Africa. But when slavery was abolished in the 20th century, many former slaves got Omani citizenship. We’re calling on Oman do the country proud and ensure that marginalized people have rights.

This interview has been edited and condensed.