Gathered together on the floor of a dusty house, Solo Sandeng’s children remember their father with a mix of sadness, anger and pride. “We want him to be remembered for what he did,” Aminata, 24, tells me, “But we also want justice.”

Her sister, Fatoumatta, 22, listens to my questions with her eyes fixed to the floor, her head wrapped in a black headscarf. When she looks up, the calm authority in her voice suggests she will continue her father’s struggle. “The Gambian government wants to silence us,” she says. “But what they did to Solo, they created an anger that will not relent.”

Sandeng, a prominent Gambian opposition politician, was allegedly beaten to death by members of the Gambian security services within hours of his arrest on April 14. That day, he and a small group of activists had taken part in a demonstration calling for electoral reform ahead of December’s presidential election.

The protest was a rare example of dissent in a country that a former army officer, Yahya Jammeh, has ruled with an iron fist since coming to power in a 1994 coup. Human Rights Watch (HRW) has documented how Jammeh’s regime uses arbitrary arrests, enforced disappearances and torture to create a climate of fear that suppresses opposition.

The government’s response to the protest in April was a stark reminder of the risks that opposition parties face in the run-up to elections. “In a country where there was any sort of democracy, my father’s actions would have been taken with grace,” Fatoumatta told me. Instead, Gambian police quickly descended on the protest, arrested Sandeng and his fellow protesters and eventually charged 25 with public order offenses. Several allege that, like Sandeng, they were badly beaten while in detention.

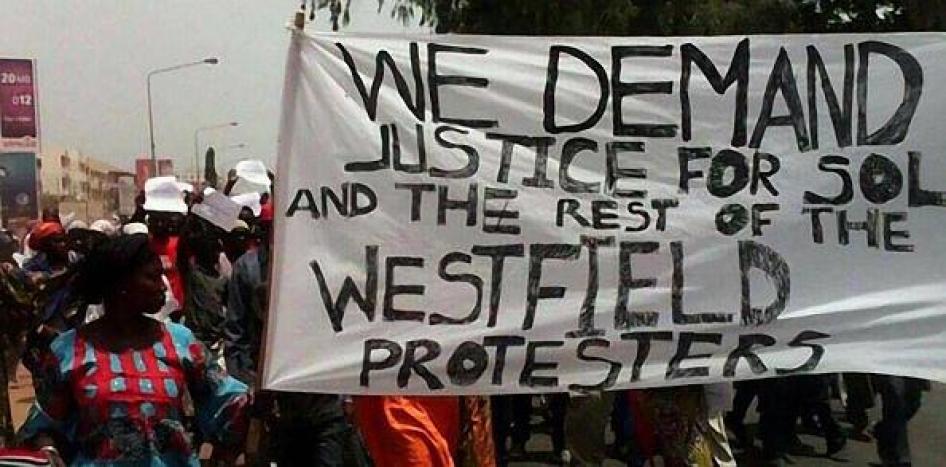

Upon hearing media reports of her father’s death in the early hours of April 16, Fatoumatta and her brother, 19-year-old Muhammed, marched with leaders of Sandeng’s political party, the United Democratic Party (UDP), toward the police headquarters where Sandeng had initially been detained. The demonstrators chanted, “Release Solo Sandeng, Dead or Alive.”

Fatoumatta recalled that as they walked, she kept thinking that “after all they did to Solo, they will leave us alone.” But the police fired teargas to disperse the crowd and beat protesters with batons. Fatoumatta escaped after being ushered hastily into a taxi. Muhammed was chased by police officers and struck on the arm, but eventually got away. More than 20 other protesters, including UDP leader Ousainou Darboe and several UDP executive members, were arrested.

News of Sandeng’s death and the arrest of the UDP leadership led to widespread condemnation from African human rights bodies, the United Nations, the European Union, and the United States. President Jammeh responded in May, saying that human rights groups and U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon could “go to hell.” On June 22, Saihou Omar Jeng, a senior official at Gambia’s National Intelligence Agency, stated that Sandeng had died in custody of “shock” and “respiratory failure” but provided no explanation of the circumstances that led to his death.

Half an hour after Fatoumatta and Muhammed arrived home on April 16, a police convoy drove up to their gate. They understood what it meant. “Family members of people involved in the April 14 and 16 protests were being targeted,” Fatoumatta says. “So we knew it wasn’t safe, we never went back to our house.” A subsequent protest on May 9 in solidarity with those arrested on April 14 and 16 was quickly suppressed.

Now in exile, Sandeng’s children hope that people remember the call for electoral reform that led to their father’s death. On July 20, Darboe and several UDP executives were sentenced to three years in prison, meaning the UDP’s leadership will remain in detention during the upcoming presidential elections. Eleven protesters arrested with Sandeng were also sentenced, on July 21, to three years in prison.

Gambian government officials told HRW that opposition groups are able to operate without restrictions. But leaders from opposition parties decry their lack of access to media, with state radio and television dominated by Jammeh and the ruling party. An inter-party dialogue intended as a forum to discuss electoral reform has stalled.

As the elections approach, the U.S. and EU should consider imposing targeted sanctions—such as travel bans and asset freezes—on senior officials implicated in human rights violations unless the government begins an impartial and transparent investigation into Sandeng’s death, releases all peaceful protesters, and engages in a genuine dialogue over electoral reform. The Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) should consider suspending Gambia from ECOWAS decision-making bodies if the human rights situation does not improve, and improve quickly.

Fatoumatta hopes that her father’s death will be a turning point for Gambia. But she acknowledges that the threat of arrest still stifles independent voices. “Fear still rules in Gambia,” says Fatoumatta. “Only if that changes can we really talk about free elections.”

Jim Wormington is an Africa researcher at Human Rights Watch. He tweets @jwormington.