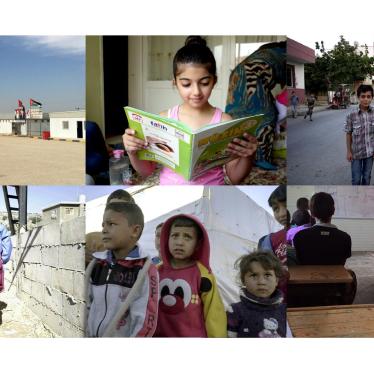

“We can’t afford to put them in school here. All my children were studying in Syria, but if I would put them in school here, how would I live?” “Muna,” 45, and her family live across the street from a school in Mount Lebanon, but her children, “Yousef,” 11, and “Nizar,” 10, have never set foot in a Lebanese classroom. Instead, they sell gum on the street to help their family pay for rent and food. “Even if everything was free, the children couldn’t go to school,” she said. “They are the only ones that can work.”

Lebanon has taken in more than 1.1 million Syrian refugees since the start of the Syria conflict in 2011. Of this number, 500,000 are school age, 3 to 18. But despite the Education Ministry’s significant efforts to ensure that all children can enroll in education, more than 250,000 Syrian children are still out of school.

My research for a new Human Rights Watch report found that despite the government’s decision to allow Syrians to enroll in public schools for free, with the assistance of international donors, several barriers are still keeping them out of the classroom.

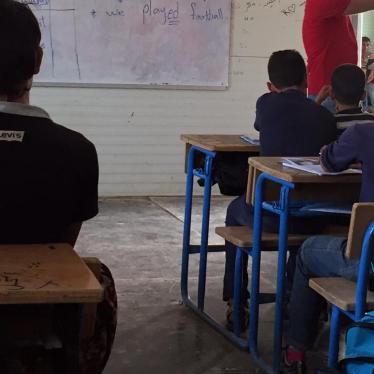

Some school directors are imposing arbitrary enrollment requirements, like asking Syrians to provide valid residency in Lebanon—despite the Education Ministry’s policy, which does not require residency for enrollment. Students are also struggling to understand classes taught in English or French, without adequate language support. And children with disabilities and secondary school-age children face particularly acute obstacles.

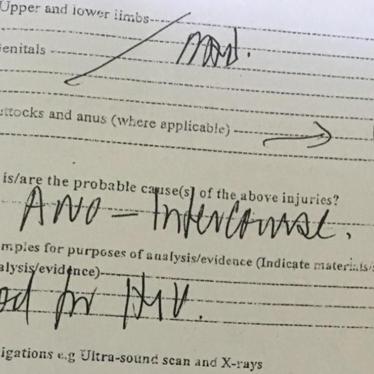

But our research found that access to education is also inextricably tied to the deteriorating living conditions of Syrians in Lebanon. Seventy percent of Syrians lived below the poverty line of US $3.84 per person per day in 2015. Many simply cannot afford to pay for basic school-related costs like transportation. Increasingly, they are pulling children out of school and relying on child labor to survive. New residency regulations introduced in January 2015 have made it difficult or impossible for Syrians to maintain legal status in Lebanon, and an estimated two-thirds of refugees now lack residency and are unable to move around to find work for fear of arrest.

Lebanon cannot address the challenge of educating Syrian children alone. But there are clear steps that the Lebanese government can take to address this major issue. It can revise its residency policy to ensure that Syrian adults can look for work without fear of arrest and can afford to keep their children in school. A policy that ensures that Syrians have proper documentation and are able to sustain themselves is in Lebanon’s own interest.

Lebanon needs international investment in livelihood programs to create jobs and strengthen the country’s economy in order to address living conditions that are deteriorating for everyone.

The World Bank estimates that the conflict in Syria has cost the country $13.1 billion since 2012, Lebanese officials said in February. The impact of the conflict on Lebanon is real. But, the refugee presence is also an opportunity to use international attention and funding to bolster the country’s weak infrastructure and limited services.

In the education sector, international funding is already improving a public school system that struggled even before the current refugee crisis, when the families of only 30 percent of Lebanese children chose to send their children to public schools. Donors are funding projects to rehabilitate schools, train teachers, and last year covered enrollment fees for 197,000 Lebanese children.

Other countries hosting Syrian refugees have developed plans to stimulate economic growth. For example, on July 12, the European Council approved a measure to improve Jordan’s access to the European Union (EU) market by relaxing the EU rules of origin for 10 years, with the goal of creating 200,000 jobs for Syrian refugees. This would allow them to contribute to the economy without competing for jobs with Jordanian citizens.

At a major donor conference in London in February, Lebanon proposed several projects to bolster the economy and create jobs, including through investments in municipalities and national-level infrastructure. It also acknowledged the need to review existing residency and work regulations for Syrians. But so far, little has changed.

There is a real need for private sector engagement with international donors, humanitarian agencies, and government officials to develop innovative solutions to the livelihood problem in a way that improves the living condition of Syrians and their host communities while benefitting the country in the long term.

It’s in Lebanon’s best interests to ensure that a quarter of a million children are not left out of school here, but can get an education and develop the tools they need to eventually rebuild Syria. But this is also an opportunity for Lebanon to attract investment and bolster basic services and infrastructure, all while ensuring that Syrians can afford to send their children to school.