(Washington, DC) – The Venezuelan government has targeted critics of its ineffective efforts to alleviate severe shortages of essential medicines and food while the crisis persists, Human Rights Watch said in a report released today. Regional governments should press the administration of President Nicolás Maduro to adopt immediate measures to better address the profound humanitarian crisis, including by exploring avenues for increased international assistance.

The 78-page report, “Venezuela’s Humanitarian Crisis: Severe Medical and Food Shortages, Inadequate and Repressive Government Response,” documents how the shortages have made it extremely difficult for many Venezuelans to obtain essential medical care or meet their families’ basic needs. The Venezuelan government has downplayed the severity of the crisis. Although its own efforts to alleviate the shortages have not succeeded, it has made only limited efforts to obtain international humanitarian assistance that might be readily available. Meanwhile, it has intimidated and punished critics, including health professionals, human rights defenders, and ordinary Venezuelans who have spoken out about the shortages.

“The Venezuelan government has seemed more vigorous in denying the existence of a humanitarian crisis than in working to resolve it,” said José Miguel Vivanco, Americas director at Human Rights Watch. “Its failures have contributed to the suffering of many Venezuelans who now struggle every day to obtain access to basic health care and adequate nutrition.”

The Venezuelan government has stridently denied that the shortages rise to the level of a crisis. When officials have acknowledged the shortages at all, they have blamed them on an “economic war” waged by the political opposition, the private sector, and foreign powers. The government has provided no evidence to support these accusations.

Human Rights Watch interviewed more than 100 people about the humanitarian situation in June 2016, in Caracas, the capital, and six states – Aragua, Carabobo, Lara, Táchira, Trujillo, and Zulia – and followed up by phone and other media. Researchers visited eight public hospitals, a health center on the border with Colombia, and a foundation that provides health care. Human Rights Watch interviewed people lined up at several locations to try to buy price-controlled goods as well as health care providers, people seeking medical care, people who had been detained in connection with protests linked to the shortages, human rights defenders, and public health experts.

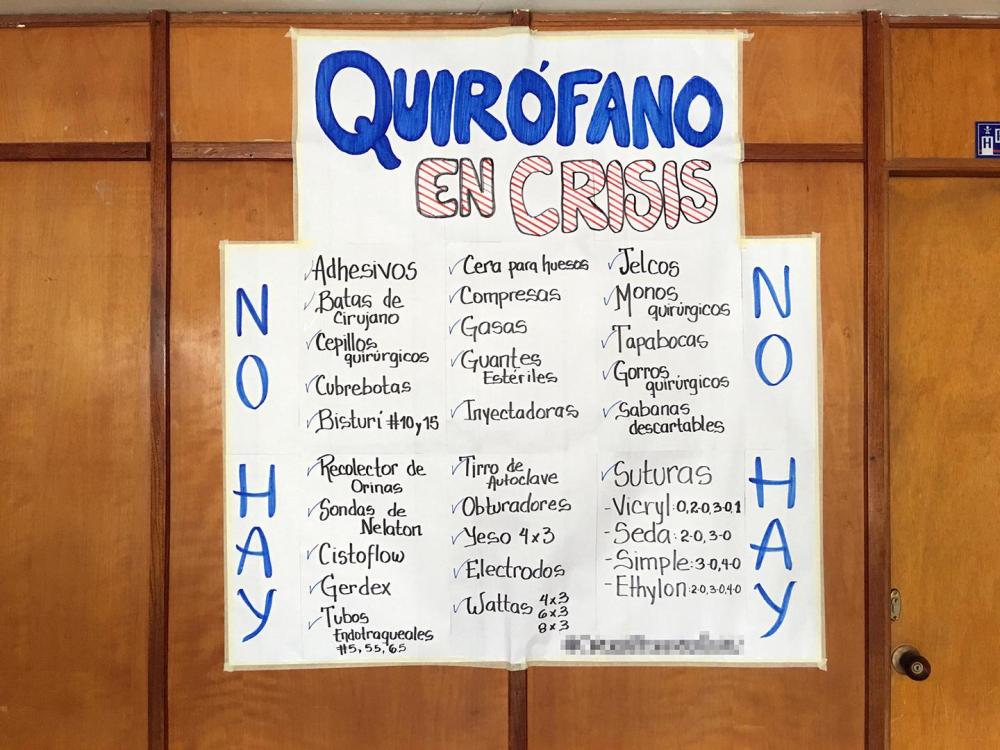

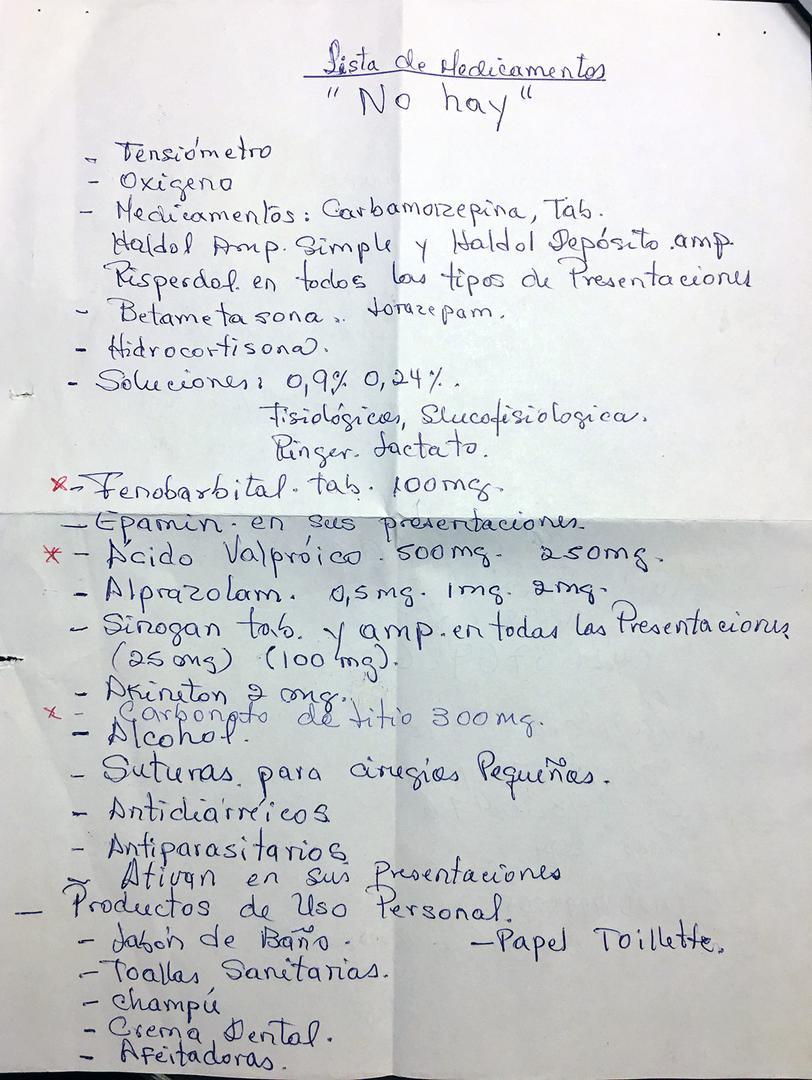

Shortages of basic medicines and other crucial medical supplies have caused a sharp deterioration in the quality and safety of care over the past two years, Human Rights Watch found. Doctors and patients reported severe shortages – and in some cases, the complete absence – of basic medicines such as antibiotics and painkillers. Supplies lacking or in short supply in public hospitals included sterile gloves, gauze, and medical alcohol.

An August 2016 survey by a network of more than 200 doctors found that 76 percent of the public hospitals where they worked lacked the basic medicines that the network said should be available in any functional public hospital.

In case after case, people facing emergencies and those with chronic medical conditions such as cancer, hypertension, diabetes, and epilepsy, as well as organ transplant patients, said they struggle to find essential medications. The medicines are often unavailable at both public and private pharmacies, are prohibitively expensive if purchased abroad, and are either unavailable or so expensive on the black market – where they also come with no quality guarantees – as to be virtually unobtainable.

The “distress and uncertainty is a daily nightmare,” the mother of a 9-year-old girl with diabetes said about her efforts to find the medicines her daughter needs.

Human Rights Watch researchers found long lines forming whenever supermarkets received goods subject to price controls. People waiting in lines said they were trying to buy items such as rice, pasta, flour, diapers, toothpaste, and toilet paper. Supermarkets often ran out of limited stock long before everyone in line had been served.

In a 2015 survey by independent groups and two leading Venezuelan universities, 87 percent of 1,488 people interviewed in 21 cities throughout the country, most from low-income families, said they had difficulty purchasing food. Twelve percent said they ate only one or two meals a day.

Public health scholars have linked food insecurity in diverse Latin American countries with major physical and mental health problems among adults, and poor growth and socio-emotional and cognitive development in children. In Venezuela, several doctors, community members, and parents told Human Rights Watch that they were beginning to see symptoms of malnutrition, particularly in children.

The government’s narrative of “economic war” has provided a rationale for using authoritarian tactics to intimidate and punish critics. It has lashed out at medical professionals who express concern about shortages, threatening to remove them from their positions at public hospitals. It has threatened to cut off the international funding of human rights organizations. And it has responded both to planned marches and spontaneous demonstrations about shortages with severe beatings, detention, and unjustifiable prohibitions on protests. Some people have been prosecuted in military courts, in violation of their right to a fair trial.

The Venezuelan government should take immediate and urgent steps to articulate and carry out effective policies to address the crisis, including by seeking international humanitarian aid, Human Rights Watch said. It should stop intimidating and punishing critics. Member countries of the Organization of American States should maintain close and continuous oversight of the situation, until the Venezuelan government shows results addressing the political and humanitarian crisis. United Nations humanitarian agencies should publish an independent assessment of the extent and impact of the shortages, as well as what is needed to address them.

“Without strong international pressure, in particular from the region, the Maduro administration may well fail to do what is necessary to alleviate this crisis, and the dramatic consequences of the humanitarian crisis that Venezuela is facing may only get worse,” Vivanco said.

Selected accounts from Venezuelans interviewed by Human Rights Watch:

- “Carlos Sánchez,” 33, of Maracay, Aragua State, was diagnosed with Hodgkin’s lymphoma in October 2015. For his first operation, Sánchez had to buy medicines and supplies, including painkillers, antibiotics, and saline solutions, and take them to the hospital, said his wife, “Ana Vargas.” Vargas said she has used WhatsApp messages and social media, including Instagram and Facebook, to ask for the medicines that Sánchez needed for the operation and has needed since. She has been unable to find them in local pharmacies. Vargas, who works for a government agency, requested that their names be withheld for fear of losing her job or having greater difficulty helping her husband get treatment at public institutions.

- The parents of Carol Jiménez, a 9-year-old girl with diabetes in Valencia, Carabobo State, have found it extremely difficult since mid-2014 to find insulin to control her blood sugar and reactive strips to measure her blood sugar levels, said her mother, Deysis Pinto. Before, Pinto said, “Things were normal, we could go to the pharmacy and even to the laboratories in the hospitals” and find what she needed. Pinto now dedicates her energy to finding the necessary medicines, and although she has succeeded, the “distress and uncertainty is a daily nightmare.” She said they rely on social networking with other diabetics, including through Twitter, Instagram, and WhatsApp group messages, to search for medicines at pharmacies in other parts of the country. Because Jiménez has been unable to receive medications shipped from other parts of the country, she has had to wait for someone to travel to Valencia from wherever they were available to deliver her medicines. “That’s how we’ve been able to get the treatment that keeps our children alive,” Pinto said.

- Sandra Silva, the 33-year-old mother of a toddler who frequently develops high fevers with convulsions, has been unable to purchase acetaminophen or paracetamol for her son in Táchira State for over a year, she said. On a recent occasion when she took her son to a public hospital, doctors were unable to provide him with any medicines, telling her to bathe the boy to stop the fever from going up, she said. Silva said she had been buying her son’s medicines in Colombia, where they cost almost 10 times as much as in Venezuela.

- Lizbeth Hurtado, a 30-year-old patient in Caracas with Crohn’s disease, a chronic gastrointestinal illness, has found it difficult to obtain her medication since mid-2015. Hurtado said she has had to interrupt treatment, causing a worsening of symptoms including weight and hair loss, intestinal problems, and skin eruptions. Hurtado has been posting her searches for medicine on social media, and has created a network of people who suffer from similar illnesses to share medication when someone finds it. At times, when unable to obtain medication elsewhere, Hurtado has taken expired pills that she got through the network, she said.

- Jesús Espinoza, a 16-year-old boy in Valencia, Carabobo State, who has had three kidney transplants, has been on haemodialysis since 2013, Espinoza and his parents said. His mother said they go “from pharmacy to pharmacy to pharmacy” looking for medication, including medicines to control Espinoza’s blood pressure, which is critical to managing his condition. When medication is available, she said, “There’s always a crowd, and when it comes to your turn, they’ve run out. So you can’t get the medicine.” When that happens, mothers at the hospital sometimes exchange various types of medication that their children need, Espinoza’s mother said, which most of the time has helped her secure medication for her son.