(Nairobi) – Armed groups fighting for control of a central province in the Central African Republic have targeted civilians in apparent reprisal killings over the past three months, Human Rights Watch said today. The attacks have left at least 45 people dead and at least 11,000 displaced.

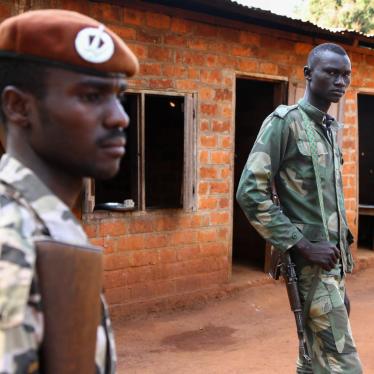

Since late 2016, two factions of the predominantly Muslim Seleka armed group have clashed heavily in the volatile Ouaka province: the Union for Peace in the Central African Republic (l’Union pour la Paix en Centrafrique, UPC), consisting mostly of ethnic Peuhl, and the Popular Front for the Renaissance in the Central African Republic (Front Populaire pour la Renaissance de la Centrafrique, FPRC), which has aligned itself with the anti-balaka – the main armed group once fighting the Seleka.

“Armed groups are targeting civilians for revenge killings in the central part of the country,” said Lewis Mudge, Africa researcher at Human Rights Watch. “As factions vie for power in the Central African Republic, civilians on all sides are exposed to their deadly attacks.”

Human Rights Watch visited Ouaka province in early April 2017, and interviewed 20 people in Bambari who had recently fled the fighting. They gave names and details of about 45 civilians (17 men, 13 women, and 15 children) who had been killed by both sides. The total number is most likely higher because scores of people remain missing.

The UN peacekeeping force in the country, the Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in the Central African Republic (MINUSCA), has deployed approximately 1,000 of its 12,870 members to Ouaka province over the past three months, but the attacks persist.

Escalating violence in the area underlines the importance of getting the newly established Special Criminal Court (SCC) up and running, Human Rights Watch said. The court – which was established by law in June 2015 – will have national and international judges and prosecutors, but will operate within the national justice system. It will investigate and prosecute grave human rights violations in the country since 2003.

The latest round of killings began in mid-February when anti-balaka fighters ambushed a group of civilians on a truck in the village of Ndoussoumba, killing at least 16 Peuhl civilians. One survivor, “Asatu,” 20, told Human Rights Watch the she jumped out of the truck when the attack began and was shot in the leg. “I saw at least 20 anti-balaka attackers and many bodies on the ground,” she said. “The anti-balaka were shooting at us from a close distance with Kalashnikovs and homemade rifles.”

Around March 19, anti-balaka fighters attacked three Peuhl men in Yassine, a town in a gold- producing area northeast of Bambari, which had been under UPC control since 2014. Two of the men died – three witnesses described both men as local butchers who had not participated in fighting. A third man said he narrowly escaped after a bullet grazed his shoulder.

In September 2014, the ICC opened an investigation into crimes in the Central African Republic since 2012. The investigation offers the chance to bring an important measure of accountability for the crimes, but will probably try only a small number of cases. The government appointed the SCC chief prosecutor in February, but the court still lacks staff and facilities. The government, UN, and partner governments should provide financial, logistical, and political support for the court to begin its work promptly, Human Rights Watch said.

Soulymane, Ousmane, and myself had killed a cow and we were about to butcher it when the anti-balaka arrived. They started shooting in the village and we all ran our separate ways. They saw me and shot at me, and the bullet grazed my shoulder but I was able to run away to the tall grass and hide. From there I watched them shoot Soulymane and kill Ousmane with a machete.

On April 7, a Human Rights Watch researcher saw scars on the survivor’s body that were consistent with his account.

On March 20, anti-balaka and FPRC fighters in the towns of Wadja Wadja and Agoudou-Manga forced the population to move to Yassine. Residents said that the fighters explained they were anticipating a UPC revenge attack on either Wadja Wadja or Agoudou-Manga and that they were forcing people to relocate for their own safety. “We asked if we could go hide in the bush, but the coalition would not allow it,” one Wadja Wajda resident said. “They wanted us in Yassine.”

Yassine had been emptied due to recent fighting, and hundreds of residents of Wadja Wadja and Agoudou-Manga sought shelter in abandoned homes on the night of March 20. Witnesses said that most anti-balaka and FPRC fighters returned to Wadja Wadja and Agoudou-Manga rather than sleep at Yassine.

At about 5 a.m. on March 21, UPC fighters attacked the largely undefended Yassine. “Marcel,” 39, said the village seemed surrounded. “There was one shot and then it seemed like from everywhere around the village they started shooting at us,” he said. “They shot automatic weapons and rockets. It was difficult to know where to run because they were shooting everywhere and targeting anyone that moved.” During the attack, the few anti-balaka and FPRC fighters who had stayed fled into surrounding woods.

“Marie,” about 40, said she recognized some of the UPC attackers. “I knew some of the men, they were Ali Darassa’s fighters,” she said. “They had come often to steal things and they were the same men who would collect taxes outside the gold mines for the UPC.”

“Faustin,” a 55-year-old resident of Wadja Wadja, said he fled into the surrounding woods:

I saw bodies as I ran. At one point, I heard a woman screaming that her husband and son had been killed. After about an hour the attack stopped and I slowly made my way back to the village. I saw many bodies in the bush. Some people had died because they had been injured, others looked like they had been killed there.

A 47-year-old resident of Agoudou-Manga, “Maurice,” said that he saw bodies of young children who died as they tried to flee into the woods. “There was a large stream that was not easy to cross,” he said. “As I came back to Yassine after the attack I saw three dead children in the stream. They had tried to cross while they were running, but they could not swim and they drowned. They were young, maybe between 3 and 5 years old.”

“Blandine,” a 30-year-old polio survivor who cannot walk, said she pretended to be dead during the attack because she could not run away. As the UPC fighters looted Yassine, they found her, stole her belongings, and told her to leave, she said. Using crutches, she walked out of Yassine, and saw at least seven dead children, three dead women, and four dead men.

One man from Wadja Wadja, “Clement,” said he lost his mother and four children in the attack:

We had moved from Wadja Wadja the night before. We were staying in a small hut at the edge of the village and the children were in front of the hut. It was hot so the children slept outside on a mat. Early in the morning I went to speak with some other men in a different part of the village. Suddenly we heard shooting. I tried to run back to where my family was but the shooting was too intense. People were falling before me, so I had to turn and flee. I ran into the bush and hid.

My wife later told me the kids were playing on the mat with the baby when the attack started. We found them there, dead on the mat. They had all been shot. I lost my 7-month-old son, my 3-year-old daughter, my 10-year-old son, and my 13-year-old daughter. My mother, who was 54-years-old, was burned in a hut where she slept. We buried my family in a hole that had been dug for a latrine. Everyone was fleeing so we could not give them a proper burial.

Attacks on Peuhl

In mid-February, anti-balaka fighters killed at least 16 Peuhl civilians when they ambushed a truck transporting people in Ndourssoumba, a village about 30 kilometers from Ippy. The group started its journey in Mbourousso and was trying to seek safety in Bambari, two survivors said. One woman, approximately 27-years-old, who lost two children in the attack, said:

We were mostly women and children. We were trying to avoid the fighting. When we entered Ndourssoumba, the anti-balaka attacked us. The truck stopped and I saw that people were already dead. The anti-balaka were very close to us because we had no weapons. They continued to shoot us. We all decided to flee. I jumped out of the truck and ran. As I ran I was shot in the foot, but I kept running. I had my son Adam [approximately a year old] on my back as I ran. I did not know it but he was shot in the back. As we ran my daughter Mariam [age 3] fell. She was shot and killed. I ran into the bush and, along with other Peuhl, we made our way toward Boyo. From there we went to Bambari. Adam was injured and he died a few days after arriving in Bambari.

Local Peuhl leaders said that other Peuhl were still in the woods and savanna in the Ouaka and Haute-Kotto provinces. Human Rights Watch interviewed one witness to the killing of a Peuhl man named Dairou in February near Baïdou, a village between Ippy and Bria. He left behind 10 children.

Attacks in Ouaka Province

In the weeks before the March 21 attack on Yassine, UPC fighters increased their attacks on civilians in Ouaka province. In January, UPC fighters attacked mines near Ouropo, on the road between Bambari and Alindao. “Pascal,” a 21-year-old resident of Ouropo, said:

The UPC attacked us as it was getting dark. There was nothing for us to do but run. I ran into the bush where I hid for six days. Over those days, I found the bodies of family members. My sister, Pulschirie Ndakala, was killed. She was seven months pregnant. My twin brother Lucien was also killed. Animals ate his body but we recognized him from his clothes.

Around the same time as the attack on Ouropo, UPC fighters attacked Kpele, killing two civilians, and Moko, killing at least four. A witness to the attack in Moko said he ran into the woods and watched as UPC fighters pillaged goods, burned homes, and targeted civilians. Local officials from both Ouropo and Moko said they recognized the attackers as UPC fighters under the command of a man based in Alindao known as Bin Laden.

Accountability and International Law

In 2014, the then-transitional government referred the situation in the Central African Republic since August 1, 2012, to the ICC. The ICC opened an investigation in September 2014, but has yet to administer any charges.

Given the ICC’s limited mandate and resources, the SCC offers a meaningful opportunity to bring wider accountability in prosecuting commanders from all parties to the conflict who are responsible for war crimes, such as those committed by the anti-balaka, FPRC, and UPC. The court needs sustained international support.

On February 15, President Faustin-Archange Touadéra named Col. Toussaint Muntazini Mukimapa, attorney general of the armed forces of the Democratic Republic of Congo, as the lead prosecutor for the SCC, but many other positions have not been filled. Systems to protect witnesses and court personnel are not yet in place, but are essential for the court to function. The government should make the court a priority and create a schedule with clear deadlines to put it in operating order.

Targeted killings of civilians violate international humanitarian law and may be prosecuted as war crimes. International humanitarian law also strictly prohibits parties to a conflict from targeting for reprisals civilians or fighters who have ceased to take a direct part in hostilities.