(Brussels) – Rwanda’s military has routinely unlawfully detained and tortured detainees with beatings, asphyxiations, mock executions, and electric shocks, Human Rights Watch said in a report released today.

The 91-page report, “‘We Will Force You to Confess’: Torture and Unlawful Military Detention in Rwanda,” documents unlawful detention in military camps and widespread and systematic torture by the military. Human Rights Watch found that judges and prosecutors ignored complaints from current and former detainees about the unlawful detention and ill-treatment, creating an environment of total impunity. Rwandan authorities and United Nations bodies should investigate immediately.

“Research over a number of years demonstrates that military officials in Rwanda can use torture whenever they please,” said Ida Sawyer, Central Africa director at Human Rights Watch. “Impunity for unlawful detention and the systematic use of torture has led many victims to give up all hope for justice.”

Human Rights Watch has confirmed 104 cases of people who were illegally detained, and in many cases tortured or ill-treated, in Rwandan military detention centers between 2010 and 2016. The total number is most likely much higher, due to the secret nature of the abuses and many former detainees’ fear of reprisals. Human Rights Watch has received several credible reports of cases in 2017, indicating that these violations have continued.

Most victims appear to have been detained on suspicion of being members of, or working with, the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (Forces démocratiques pour la libération du Rwanda, FDLR). Some members of the predominantly Rwandan Hutu armed opposition group, based in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo, participated in the 1994 genocide in Rwanda. The group has committed, and continues to commit, horrific abuses against Congolese civilians in eastern Congo, sometimes in alliance with Congolese armed groups.

Other victims were accused of collaborating with the Rwanda National Congress (RNC), an opposition group in exile composed mainly of former members of Rwanda’s ruling party, or with Victoire Ingabire, president of the Forces démocratiques unifiées (FDU)-Inkingi, a banned opposition party. Ingabire is serving a 15-year prison sentence for conspiracy to undermine the government and genocide denial.

Human Rights Watch interviewed 61 former detainees and more than 160 family members and friends of people who were tortured between 2010 and 2016, as well as government and military officials, some of whom requested anonymity. Human Rights Watch also observed the trials of seven groups of people who said they were tortured while held unlawfully at military detention centers, and reviewed court statements regarding 21 illegal detention cases and statements given in court by 22 people.

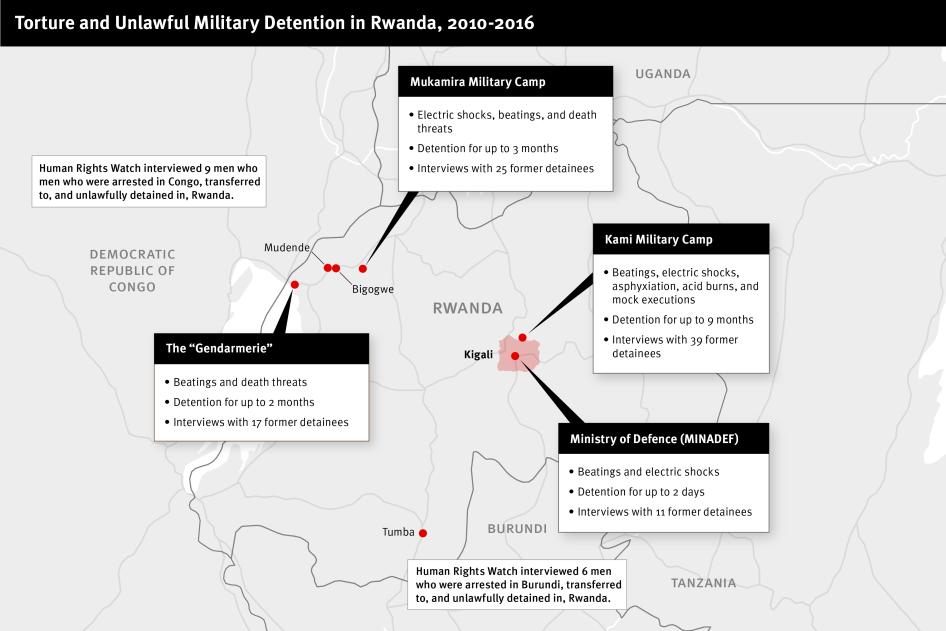

In the cases documented, detainees were held at unofficial military detention centers, including the Defence Ministry (known as MINADEF), Kami military camp, Mukamira military camp, a military base known as the “Gendarmerie,” detention centers in Bigogwe, Mudende, and Tumba, and private homes used as detention centers. Human Rights Watch is not aware of any Rwandan laws or statutes allowing detention at these locations.

The Rwandan government did not reply to numerous letters from Human Rights Watch presenting the findings and requesting a response to specific questions. However, the government has publicly asserted, on multiple occasions, that unofficial detention does not exist in Rwanda. With regard to Kami military camp, which is consistently identified as a location where authorities have interrogated and tortured detainees, Justice Minister Johnston Busingye said in March 2016, during a review before the UN Human Rights Committee, that “no interrogation of suspects is carried out” and “no people are imprisoned there.”

Many of the detainees, including civilians and former FDLR combatants, were arrested in Rwanda by Rwandan soldiers, sometimes assisted by police, intelligence, or local government officials. Others were arrested and ill-treated in neighboring Burundi or Congo, some while being processed through the demobilization and repatriation program supported by the UN peacekeeping mission in Congo. They were then illegally transferred to Rwanda, where they were abused.

In most cases, victims were interrogated, ill-treated or tortured, and forced to sign confessions, often based on fabricated allegations, while they were victims of an enforced disappearance. They were then eventually taken before prosecutors, who often pressured suspects to confirm their confessions and, to the best of Human Rights Watch’s knowledge, did not investigate alleged abuses during detention. Some detainees were released as suddenly and as arbitrarily as they had been arrested, often in groups, without any charges or judicial procedure.

Many said that torture sessions began immediately when they arrived at the military detention center. Many were handcuffed while soldiers slapped and punched them or beat them with sticks. “[When we arrived] at Kami, I was still blindfolded,” one former detainee said. “They told me to lie on the ground. Two soldiers stood on me, one on my head and one on my feet. They stood on me and beat me. Then they made me curl up into a ball, tied me up, and pulled my legs and arms. They did this for hours and kept telling me to confess.”

If the suspect failed to give the soldiers the answers they wanted, the beatings continued, often several times a day. Other detainees described asphyxiation, electric shocks, mock executions, and tying objects to men’s genitals. Some detainees’ hands were handcuffed to their legs for months on end, with soldiers only taking the handcuffs off so the men could use the toilet. Many former detainees told Human Rights Watch, prosecutors, or judges that they signed false statements because they could not stand the torture or believed they would die.

The violations are a clear breach of Rwandan and international law, which absolutely prohibit enforced disappearances, arbitrary and unlawful arrest and detention, and the use of torture and other ill-treatment. Under international law, torture and enforced disappearances are crimes subject to universal jurisdiction, meaning any country may prosecute them irrespective of where the crimes took place or the nationality of abuser or victim.

On June 30, 2015, Rwanda ratified the Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture, allowing visits to detention sites by the protocol’s Subcommittee on Prevention of Torture. The protocol requires governments to set up a national mechanism to prevent torture at the domestic level. The Rwandan government has yet to create it, despite a deadline of one year after ratification. However, a process to establish the mechanism has started. There are indications that Rwanda’s National Commission for Human Rights will manage it. In 2003 the commission investigated some cases of people held in military detention, but has shown a reluctance to do so in recent years.

Human Rights Watch wrote to the commission in January and August, 2017, to share information on torture cases and to request a response to specific questions, but got no response. The commission should demonstrate the independence and courage to investigate these sensitive cases if the national preventive mechanism is to be anything more than a cover for these crimes, Human Rights Watch said.

The subcommittee plans a state visit to Rwanda in mid-October. The Committee Against Torture, the body established by the Convention against Torture to monitor compliance by state parties, will review Rwanda’s compliance later in 2017. The subcommittee should visit areas of unlawful detention and torture, and the committee should ensure that Rwanda takes torture allegations seriously and carries out credible investigations, Human Rights Watch said.

Failing a serious effort by the Rwandan government to confront systematic torture, donors should evaluate financial and other support, including training and capacity-building, to institutions directly involved in these violations.

“The Rwandan government has every right to protect its citizens from armed groups like the FDLR, but allowing the military to commit heinous crimes only creates mistrust in the government,” Sawyer said. “To demonstrate its respect for the rule of law, and to put an end to these horrible practices, the government should immediately investigate and prosecute those responsible for unlawful detention and torture.”