(Beirut) – The Egyptian government campaign against an affiliate of the Islamic State group in North Sinai has left up to 420,000 residents in four northeastern cities in urgent need of humanitarian aid since February 9, 2018, Human Rights Watch said today. The government should provide sufficient food for all residents and allow relief organizations such as the Egyptian Red Crescent to immediately provide resources to address local residents’ critical needs.

The military campaign against the Islamic State-affiliate in North Sinai has included imposing severe restrictions on the movement of people and goods in almost all of the governorate. Residents say they have experienced sharply diminished supplies of available food, medicine, cooking gas, and other essential commercial goods. The authorities have also banned the sale or use of gasoline for vehicle use in the area and cut telecommunication services for several days at a time. The government has cut water and electricity almost entirely in the most eastern areas of North Sinai, including Rafah and Sheikh Zuwayed.

“A counterterrorism operation that imperils the flow of essential goods to hundreds of thousands of civilians is unlawful and unlikely to stem violence,” said Sarah Leah Whitson, Middle East and North Africa director at Human Rights Watch. “The Egyptian army’s actions border on collective punishment and reveal the gap between what President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi claims to be doing on behalf of the citizenry and the shameful reality.”

The authorities prohibit independent reporting from the affected areas. Human Rights Watch interviewed two media workers living in North Sinai and 13 North Sinai residents or their relatives, including two activists, and reviewed footage, satellite images, official statements, media reports, and social media posts. Human Rights Watch concluded that if the current level of movement restrictions continues, it could lead to a wider humanitarian crisis in an already economically marginalized area that continues to suffer from ongoing military operations and home demolitions.

On February 9, the government announced the beginning of “Sinai 2018,” a new phase of the military campaign against Islamist militants that started in 2013. Most of the militants belong to an Islamic State affiliate that calls itself “Sinai Province.” The government plan came shortly before the end of a three-month deadline to the army from al-Sisi to “restore stability and security” in the region using “all brute force.” The deadline followed a November 24, 2017 attack by gunmen on a Sufi Mosque in North Sinai that killed 305 civilians. No group claimed responsibility, but survivors told prosecutors that the attackers brandished the Islamic State flag.

Witnesses interviewed in the affected areas said the operation has included closing roads, isolating cities from each other, and isolating the North Sinai governate from Egypt’s mainland, severely affecting the flow of goods from the mainland. The army has become the main source of food, giving some away and selling the rest. But local people said the quantities distributed do not meet existing needs. The crisis is most serious in the eastern cities of Rafah and Sheikh Zuwayed where road closures are stricter, security restrictions have long existed, and private markets have near-completely run out of goods.

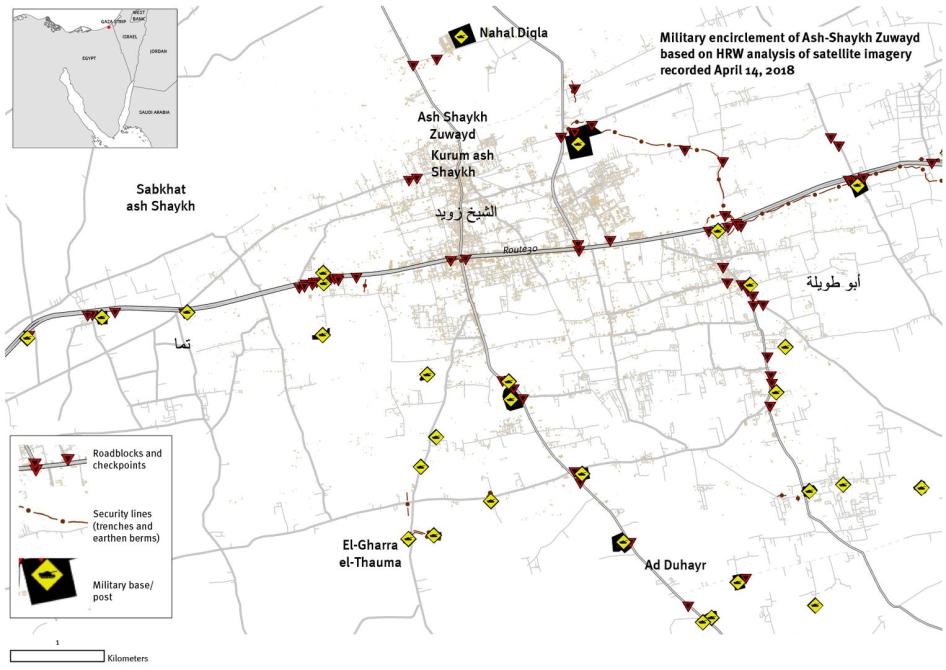

Human Rights Watch analysis of satellite imagery recorded after the start of operation “Sinai 2018” between February 22 and April 14, 2018, suggests local civilian road traffic has fallen dramatically as a consequence of the military operation in the area. This is consistent with witness testimony. The city of Sheikh Zuwayed in particular is effectively surrounded by a network of military bases and posts, and physical access appears highly restricted. All main roads entering and leaving the city are either physically closed or controlled with military checkpoints.

The absence of sufficient government measures to deal with the food crisis has stirred fears and led to incidents of violence. On March 9 in al-Arish, the army fired gunshots to disperse a crowd of residents who gathered to buy food, and resulting shrapnel wounded several, news reports said. In a separate incident in Rafah on March 20, soldiers’ gunfire killed two children and injured other people in a crowd that had gathered to obtain food, a source from Sheikh Zuwayed, who requested anonymity, told Human Rights Watch.

Officials have denied that there is a food crisis. On March 11, the army spokesperson said that the army continued to “provide food convoys and open several facilities to sell food and goods and other life necessities at discounted prices.” On March 30, Harhor said in a media statement that food “sufficient for six months” was delivered for sale to Sinai markets. But residents and activists said the situation is a humanitarian crisis and that traders should not be allowed to take advantage of the food shortage to increase profits. Human Rights Watch emailed the Egyptian Red Crescent on March 19 and April 15 to inquire whether it was carrying out humanitarian operations in the province but received no response.

The army’s failure to allow free movement and to allow sufficient food and other life essentials to reach residents violates rights enshrined in Egypt’s constitution and in its binding obligations under international treaties, especially the International Covenant for Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), the International Covenant for Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), and the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights. In particular, they amount to severe violations of the right to food, as defined in UN criteria that explain Article 11 of the ICESCR, including that the state needs to ensure the availability, accessibility, and adequacy of food. The military has also violated the right to food by destroying farmland that residents relied on for food, apparently using an indiscriminate, blanket security justification that farms hide militants, and without ensuring residents have alternative access to adequate food.

The right to food is strongly linked to other rights such as the rights to life, health, and education – and government obligations to ensure all have sufficient food is particularly important during times of crisis. The army actions in North Sinai most likely amounts to collective punishment of local residents and discrimination against the Bedouin community.

Human Rights Watch said in 2015 that the situation in Sinai could amount to a non-international armed conflict. In armed conflicts, under international humanitarian law, all parties must allow and facilitate rapid and unimpeded passage of humanitarian relief for civilians in need.

The army has not announced a detailed justification for the near-complete isolation of the neighborhoods and the cities in the governorate, but army statements mentioned “cutting supplies” to armed groups and preventing militants from escaping to Egypt’s mainland. Under humanitarian law, all parties are requested to ensure the unimpeded flow of humanitarian aid and to ensure that civilians can flee unsafe zones.

“Instead of unleashing its usual propaganda machine to claim that criticizing Egyptian security forces undermines its counterterrorism efforts, the government should adhere to the law and stop punishing an entire community,” Whitson said.

Human Rights Watch interviewed two media workers who live in North Sinai; eight families who live in the cities of al-Arish, Sheikh Zuwayed, and Rafah; and two people who live outside Egypt but are in frequent contact with their families in Sinai. Three additional interviews focused on home demolitions that have likely intensified since February 9. Human Rights Watch is still investigating the issue of home demolitions. Human Rights Watch used pseudonyms for all of the interviewees, except one activist, for their protection. Human Rights Watch also reviewed scores of news articles, social media posts, satellite imagery, and videos, as well as footage broadcast on the official army spokesperson’s Facebook page.

Severe Restrictions

On January 19, President al-Sisi said “we made a decision to use extreme violence and truly brute force [in Sinai] … We haven’t started yet.”

Witnesses and media reports indicate that the army and the police have most likely arbitrarily arrested hundreds of people, including women, but released some of them.

Ashraf Hefny, a local activist and coordinator of the People’s Committee in al-Arish, an independent gathering of family clan leaders and activists, told Human Rights Watch that residents were not warned about what he called a “siege.” Automobile service stations closed suddenly on the evening of February 8, and then “commodities began to disappear gradually and [then] quickly.”

Witnesses said that since February 9 the army has sent troops to “besiege” neighborhoods, conducting thorough house-by-house searches in each. Police forces are also involved, mainly in al-Arish. The witnesses said that security forces seized all mobile phones, and sometimes laptops, computers, and other electronic devices, and did not return them.

Human Rights Watch analyzed a detailed time series of satellite imagery recorded between 2016 and 2018 and identified an extensive network of security architecture constructed by the Egyptian army in the Northern Sinai governorate.

This network includes dozens of military bases, observation posts, road checkpoints, heavy artillery batteries and munition depots, as well as hundreds of kilometers of earthen berms and security trenches.

These security structures are located along primary and secondary roads surrounding main cities and towns in the governorate, with the heaviest concentration in the east between Rafah and Sheikh Zuwayed. The latter is completely surrounded by military posts.

The People’s Committee in al-Arish criticized al-Sisi’s statement on January 20 and said in a statement posted on its Facebook page that, “Sinai residents are threatened by the head of state,” and that the residents lived an “almost a non-existent life … Water doesn’t meet minimal needs and [they are] without electricity. North Sinai cities are dark most of the time.”

A local political activist said that “even the governor has no power.” Instead, he said, “the Defense Ministry and those who represent it are the only decision makers.” He said that the situation required aid organizations to intervene.

The North Sinai governorate has suffered from state marginalization for decades, but some unofficial statements estimate that unemployment rates might have surged to 60 percent in the governorate because of the military campaign and interruption of economic activity, particularly affecting farming.

Demolitions, Restrictions on Movement

In January al-Sisi announced a plan to forcibly evict and demolish all farms and houses within a five-kilometer circle around al-Arish airport to create an airport security buffer zone. The demolitions started soon afterward, media reports said, but no official decrees were published in the Official Gazette to lawfully frame the decision or establish a clear way for affected citizens to claim compensation. The People’s Committee said in a statement that “there are several other ways to secure the airport” and that the decision was “a pretext” to evict residents from other parts of Sinai.

Ongoing home demolitions and forced evictions in different cities have left many families with limited options. Many who could not afford to move to another city or received no compensation live in rudimentary shacks – which the army frequently calls “terrorists’ hideouts” – in the villages around Rafah and Sheikh Zuwayed. Most of North Sinai is under a state of emergency, and an evening and early morning curfew has been in effect since October 2014.

Since the restrictions began, people who were outside Sinai have not been able to return to their homes on regular routes, as the army controls al-Salam Bridge and the nearby ferry, the main transportation links between North Sinai and Egypt’s mainland. Some families have been separated for more than two months. Small numbers were allowed to return on a bus provided by the government in the nearby Ismailiya governorate.

On March 9, one month after the beginning of the restrictions, the administration of North Sinai governorate posted a link on its Facebook page for residents “stuck” outside the governorate to fill in a form and wait for the administration to contact them.

A ban on traveling to mainland Egypt appears to apply to all residents, and the army did not announce clear procedures for exceptions on those restrictions for critical medical cases.

People who want to travel to mainland Egypt have to register at the governorate administration and wait for officials to contact them. Residents said personal “connections” with security officials can facilitate permission. Official statements on the governorate’s website say that only 113 people with medical needs and their escorting relatives and 420 students were allowed to travel to Egypt’s mainland from February 9 to 25.

In Rafah and Sheikh Zuwayed, the army even seized donkeys that residents used for transportation after service stations were closed down. Al-Manassa independent news website said on March 20 that security measures were also restricting using donkeys for transportation.

Food and Water Crisis

The evidence gathered reveals that the army restrictions has exacerbated the suffering of residents already bearing the consequences of intensive military operations in their villages and cities over the past four years and caused a serious food shortage. This food crisis appears to be most serious in Sheikh Zuwayed and what remains of Rafah, a city almost entirely demolished after the government ordered almost all of its residents evicted to create a security buffer zone in 2014.

The army spokesperson released videos of women and children lining up to receive what seemed to be boxes of food distributed by the army. The same official statements, such as footage posted on April 8, show that the National Service Projects Organization, the Defense Ministry’s entity that owns and runs scores of commercial projects across the country, appears to be selling many of these supplies. The small quantities of goods that the government allowed since February might have allowed market to reopen briefly but did not resolve the crisis.

Hefny said that, “The government is dealing with an abnormal situation as if it was normal, although they themselves call it a war.” Some people had to wait for weeks to be allowed to travel and had to pay double the usual price [for the local bus], he said. “People would line up in very long lines in front of a shop without even knowing what [this shop] would be selling.”

Hefny and other witnesses said there was a bread shortage and that “exploitation by a few traders” in the absence of effective monitoring has meant that they have a monopoly on key items. He blamed the government for the crisis because the situation should be managed as in “a state of war,” he said.

According to witnesses, there is also a severe shortage of drinking water east of al-Arish, as residents rely heavily on wells that need electricity or fuel to operate. Al-Manassa reported that many residents turned to collecting rainwater for essential needs. Media reports have said before that the army also restricted the use of big water trucks after militants had used them to make bombs.

Accounts of the situation in al-Arish and Baer al-Abd

“It’s a complete humiliation … There’s severe shortage of food,” said “Tawfik,” an employee from al-Arish whose wife and child were outside Sinai when the restrictions began and who has not been able to reunite with them.

Tawfik said that he needed to see a doctor for a minor medical condition, but that without transportation, it took him several days. “Transportation is rare and expensive,” he said. “Gas is [only] sold on the black market... and people pay ten pounds [0.56] instead of two [0.11] to ride in a pick-up car.”

“My friends are struggling with [feeding] their kids because of the lack of dairy products and yogurt,” he said. “There are no eggs, no vegetables, no fruits, nothing.” Tawfik said that food is sold on army trucks and sometimes by associations that belong to the Supply and Internal Trading Ministry, the government entity that controls strategic goods. He said that the government charges the pre-restrictions market price but that the quantities are insufficient:

Quantities are limited and not available daily. The lines [of people waiting] have become very long and [the quantities] don’t suffice. I haven’t gone yet. I won’t humiliate myself for any reason.

On March 19, Mada Masr reported, citing witness accounts, that soldiers fired their guns in al-Arish to force people gathered to buy food to line up outside the distribution center, injuring four people by shrapnel. One injured woman lost her vision in one eye, but her family has not been able to take her outside Sinai for treatment because of the closure of roads.

Tawfik said that the restrictions on movement, goods, and food has interrupted local economic activities and the situation became “harsh for all business owners and workers as there isn’t considerable income. For example, who would buy clothes in such circumstances?”

Mada Masr quoted Khaled Mohamed, a man in his thirties from al-Arish, who said he waited hours for army trucks selling food to arrive two weeks after the restrictions began. The scene was “very absurd and frightening,” Mohamed said. “We were running after trucks to get food!” A few days later, people went to a vegetable market one night when they heard three trucks were arriving to sell food, Mada Masr said. A video published on Facebook by a resident in al-Arish, before he deleted it, showed dozens of al-Arish residents running after a truck that was reported to be distributing free vegetables.

Tawfik said he did not try to bring his family back to Sinai. “If the boy gets sick, I won’t find medicine or transportation to take him to a doctor.” He said there was also a shortage of some medicines. He said he met someone who was able to come back to North Sinai on the government bus: “It took them two and half days on the road instead of two and half hours.” Hospitals and medical centers in North Sinai had already been severely understaffed.

“Mahfouz,” 34, from al-Arish, said that “kids were screaming from hunger” and that “obtaining some vegetables has become a miracle.” He said that on one occasion he stood in line from 7 a.m. until 10 a.m. to buy bread. He said that now his family eats once a day, sometimes due to the lack of food, and that for the most part there was no baby formula.

Tawfik, Mahfouz, and Mohsen, another resident of al-Arish, said that the army allowed medicine companies to deliver medicine to pharmacies after initial shortages.

Residents of Baer al-Abd have faced some restrictions, but it is not as tightly controlled as other places in North Sinai. “Zaynab,” who lives close to Baer al-Abad, said that the army prevented farmers of the city from selling their vegetables, poultry, and other products in other cities in Sinai. This has led to the spoiling of crops and substantial financial losses.

Zaynab said that people in Baer al-Abd can move relatively freely, but that in al-Arish, the transportation “is almost non-existent … There are four or five buses run by the governorate administration that transport people [inside the city] for free … [but] these are very insufficient.”

The army has also prevented selling cooking gas cylinders in al-Arish, which had shortages even before the current campaign. But Zaynab said that the army allowed distributors to refill cylinders in Baer al-Abd and sell them in al-Arish five or four times since February 9. Two al-Arish residents said that they relied on electric appliances for cooking because they could not obtain cooking gas.

The government allowed more hours of telecommunications and electricity service during the presidential election days, from March 26 to 28. Mada Masr reported on March 29 that the government allowed the delivery of several food products at the al-Arish local markets, including eggs, fish, milk, and others that had not been available since February 9. Mada Masr said that people rushed to buy what was available.

Accounts of the situation in Sheikh Zuwayed and Rafah

The two main cities east of al-Arish are Sheikh Zuwayed and what remains of Rafah, a city on the border with Gaza where the army evicted most of its 70,000 residents, apparently leaving only a few thousand. Residents in these cities and villages around them are suffering from much harsher conditions, as army restrictions on goods have long existed even before the February 9 campaign. The army has become the only source of food for many, and residents report that it is sold at higher prices than before the restrictions, sometimes double the cost. People rely on wood fires and face shortages of water, medicines, and medical services.

It is not the first time that the army has restricted the delivery of food in both cities, but it is the first time the restrictions lasted for weeks. Vehicle fuel sales have been banned in these cities for years, and residents were only allowed to buy fuel in al-Arish but since February 9 this has also been banned. For example, on March 16, 2017, the privately-owned al-Shorouk newspaper reported that “commerce was about to vanish in Sheikh Zuwayed” because of army restrictions on movement of all sorts of goods. In May 2015, closure of roads to Sheikh Zuwayed and Rafah led to sharp shortages of food and medicine for almost two weeks before the army eased its restrictions. In the May 2015 crises, an unnamed official from the Supplies Ministry told the pro-government Dotmasr website that the crisis was “out of the ministry’s hands” and that army checkpoints were controlling the flow of goods. In November and December 2017, electricity was cut for three weeks.

“Mahmoud,” an Egyptian young man from who lives outside Sinai and has immediate family in Shaykh Zuwayed and Rafah, described his family’s life under the restrictions:

People come walking from all areas, [but] only those who have money. They have to pass all checkpoints and [suffer] humiliation and line up in long lines. Most of them are women because men are afraid of getting arrested. The line could be up to hundreds of people and they start lining up four hours before the [food] trucks arrive.

Mahmoud said that family members described scenes in which the army would use gunfire to frighten people into lining up for food distributions:

[One time, soldiers] fired in the air. They started shouting at people “Sit! Stand! Sit! Stand!” to humiliate them. They said, “you don’t deserve to eat … you are sons of bastards.” The last time [the army came to sell food], they left people behind and moved without selling anything. The army sells food at double the price and not of a good quality.

He said that a relative of his has a small tract of land where he used to plant some vegetables, “but [now] the vegetables were finished.” Residents could not farm because “there’s no water,” Mahmoud said. He said that to bring water, people have to go to the “Abu Taweela” area, between Rafah and Sheikh Zuwayed, passing several checkpoints, where there is a person who owns a well operated by generator. He said that his brother once bought 10 gallons, but on his way back army officers stopped him and took the water. “You are taking it to the terrorists,” the officers told Mahmoud’s brother.

“To carry water, you have to obtain permission from the army officers at the checkpoint,” he said. “It is valid for one time.” He said that people feel “humiliated,” especially when they think about their farming heritage:

Sheikh Zuwayed and Rafah were the source of vegetables, tomatoes, potatoes, oranges, and clementines. We used to produce for ourselves and export the excess, and farming was the residents’ main job.

“Now, they all eat bread, onions, and khobbeizeh, greens that grow wild in their towns. Since the restrictions began, women started looking for this plant to cook it," he said.

Mahmoud said his mother stopped telling him the details of their lives because it made him cry: “My mother was a woman with dignity. Last week, she tried to find three eggs for ten pounds [0.56 USD] and could hardly find them.”

Mahmoud said that there was no milk at their home to feed his nephews and nieces and that a relative of his, who is pregnant, “keeps fainting as she cannot find food.” “My mother told me they didn’t know where to find a doctor and that they could not find milk.” He said that al-Sheikh Zuwayed Public Hospital, the city’s only medical facility, was barely functioning. “Only a couple of nurses and maybe a general practitioner [worked] sometimes. And you have to pass checkpoints and [face] humiliation and gunfire.”

He also said that a member of his relative’s family had been outside Sinai when the restrictions began and has not been able to come back since, so the relative’s family has lost its source of income. The army seized Mahmoud’s brother’s car in Shaykh Zuwayed without offering any legal reason. “Now my brother is at home [without work] feeling oppressed and can’t even buy yogurt for his daughter,” Mahmoud said.”

Cooking gas was hard to get in the beginning of the restrictions and later completely banned, Mahmoud said. “People use wood fires to cook.” He said that his family usually ate one meal every two days, depending on how much food they found.

“Laila,” who lives in the al-Hussaynat area, between Rafah and Sheikh Zuwayed, said that she could not find enough food to feed her 10 children and grandchildren. She said she is a widow and that the army demolished their house and farm in Rafah as part of the forced evictions when they created the buffer zone. The farm was the only source of income for the family, but they received no compensation.

Laila walks dozens of kilometers to find food for her children and grandchildren and knocks on doors begging for food. Her family has also tried to hunt birds. They captured two birds in three days and made soup to feed the children.

The quasi-official Facebook page Electricity News in Rafah and Sheikh Zuwayed – a page that usually publishes news about power cuts, cable damages, and maintenance operations – published a call for help on March 5 for a three-month baby girl who needed baby formula, which her family could not find. The page said that the father, from al-Hussaynat area, was “crying and said he was feeding her cooked rice – otherwise she would die.” The page called on the army to provide milk for the baby, food, and yogurt.

It is very difficult for journalists to reach villages around Rafah and Sheikh Zuwayed, but the conditions there are probably more severe, especially in al-Masoura village, south of Rafah. On April 7, the pro-government al-Watan newspaper said that the army finally “opened al-Masoura road” to allow residents, whose houses were being demolished, to leave to al-Arish and other areas in the governorate. The report quoted Khaled Kamal, the head of Rafah City Council, who said that they “received urgent help requests” from al-Masoura residents who wanted to leave. He rejected claims that residents were trapped or prevented from taking their possessions and furniture. However, he said that they rejected requests “from families of non-evicted areas to move them” because they only facilitate the move of residents of evicted areas.