What sparked your interest in Kiribati?

The whole thing started on Panama’s San Blas islands, which are expected to be covered by rising sea water due to climate change. I went there on assignment from the New York Times to cover the issue, and I was so upset by it. And I thought, where else on the planet are people experiencing this? So I looked at a world map, and I heard about Kiribati. I wasn’t even aware of its existence. Here was a country whose ocean territory was as wide as the United States, in the middle of the Pacific, and I never heard of it. I was just amazed. I went there for two weeks to work as a photographer. I didn’t plan to make a movie.

How did you meet President Tong?

I had chartered a plane to take aerial photographs, and the pilot was a close friend of his, and he introduced us. I was quite shy. He was a head of state that knew that within a century, he won’t have a state anymore. What’s a bigger challenge than that? I just spontaneously asked him about making this movie. And he said yes. I had never made a movie before, never even done a short film. So I figured, “OK let’s do this, let’s figure out how to make a film.” It was the start of a four-year journey.

Throughout the movie, Tong eloquently speaks to world leaders about climate change and his country. What was it like to film this?

When I learned he would meet with the pope, I flew to the Vatican and met him. I did that whenever he met heads of state, was at the UN Human Rights Council, or any important moment. I basically covered every important meeting he had for the whole three years. I can tell you, in this political arena, the action is really fast and extremely boring. You go there, shake hands with Obama, and that’s it. It’s waiting hours and hours for the next meeting.

What’s your relationship like with Tong?

I was a one-man show, and because I was just a regular guy with a camera, I got more and more access. It got to the point where I was sharing dinner and having wine with him. Now we have almost like a grandfather-grandson relationship.

When I look back over the past five years, I see how I tried to keep my professional distance from the story, and I wonder, what just happened? How in the world did a Swiss white guy just become so close to the president of Kiribati?

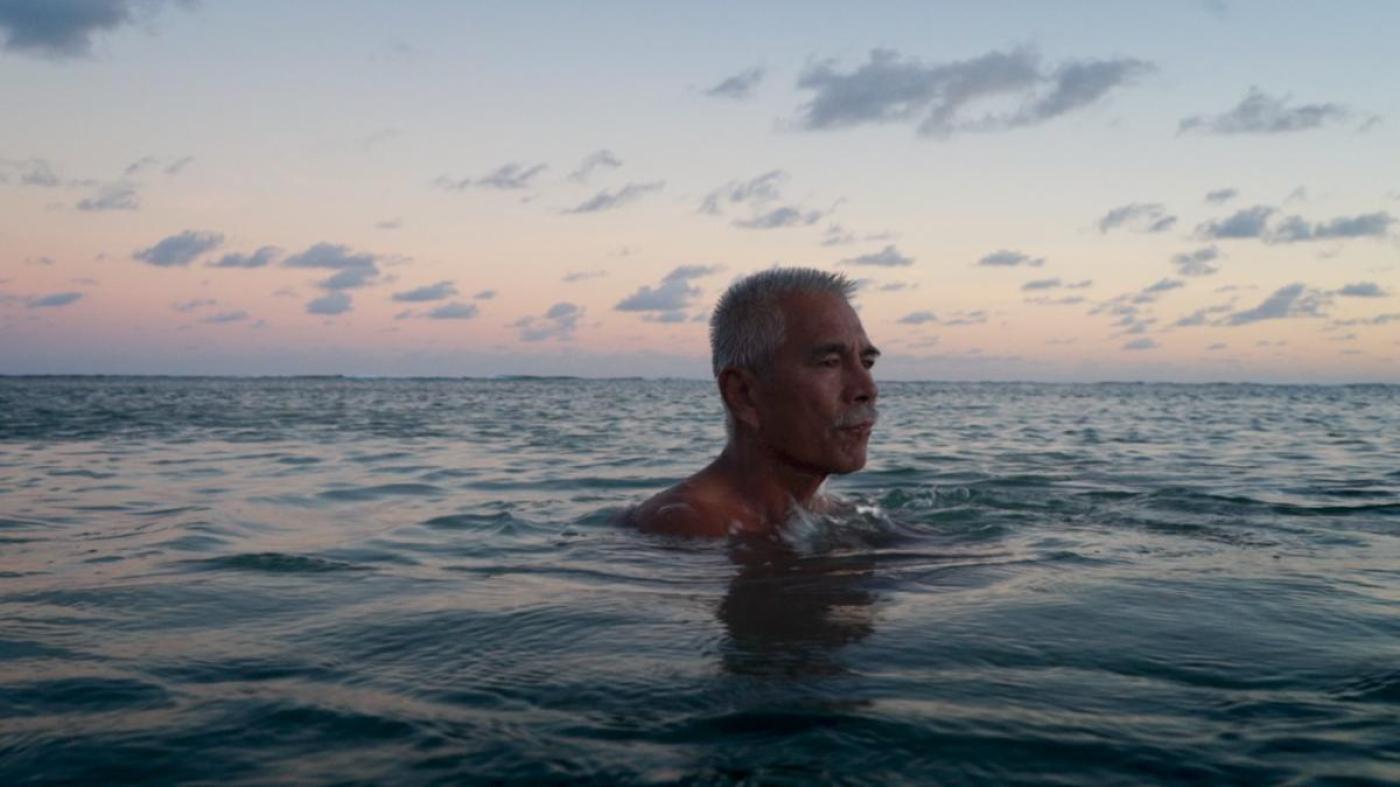

What is Tong like in person?

You go to his home, what you’ll discover is that he is a traditional fisherman, living in a simple house with his grandchildren. There is only cold water. He spends his days on the lagoon fishing, and at night he spends time with his family and tells stories. He’s an elder respected by the community, and he drinks Kava, a traditional drink, and has a very important relationship to the spiritual world. So, he’s a mix of a traditional fisherman and something like a shaman. You would never ever think of him as the same guy hanging out with the pope. It’s an incredible contrast.

Your story also focuses on a Kiribati woman named Tiermeri Tiare, known as Sermary, who was able to get a visa to live in New Zealand with her family. Why did you choose her?

Through Sermary you can understand the legacy of the people in Kiribati and what they’re going through. They have this program called “Pacific access category.” Every year they pick 75 people from Kiribati, a bit like a lottery, and those people can migrate to New Zealand. I basically got in touch with one of my friends in Kiribati who had contacts with the high commissioner, and from them I got the list of people who had won. All people still living in Kiribati who in a year or two would be in New Zealand. Sermary She was the first person I called. I just knew she was perfect.

In the movie, you see Sermary struggling to adjust to life in New Zealand. In one scene you see how, right after she landed in Auckland, she’s completely overwhelmed by the airport’s parking lot.

There is only one road in Kiribati, and it’s 23 kilometers long. That’s the only place on Kirbati with a few cars. In another scene we cut from the movie, Sermary and her friend drive out of the airport and into an Auckland suburb. Sermary looks at the houses and asks, “Why are there so many classrooms in this country?” In Kiribati, the only buildings with walls are classrooms, built by the church. People there don’t live in houses. And I think that’s an important perspective. All their lives they didn’t have walls. And they don’t have worry about the rent or buying food. There’s nothing to buy on the islands, although they do trade some coconuts for tea or sugar. When I was there, I wanted a cup of tea, and the vendor asked me for half a coconut. I only had an Australian dollar and offered it to him, but he had no use for the money. And I thought, ”Wow.” Leaving this culture is an incredible life change.

Before she left for New Zealand, Sermary’s home flooded for the first time in an unusual storm. But when she talked to her friends of the rising water and the need to leave Kiribati, no one agreed. President Tong also spoke of people in Kiribati not believing climate change endangered their islands. Were you surprised to find those views there?

For me, this is the very point of the movie. Tong says again and again, “Climate change should not be a political issue.” Meanwhile, politicians play their electoral games. In Australia, in Kiribati, politicians deny the existence of climate change to win some votes, and they’re playing with the future of this planet. The story of Kiribati is a warning to the rest of humanity. It’s too late for Kiribati. It’s too late for Manhattan, too. It’s just a question of time. And a very important question is, how are you going to deal with that? For me, the main point about the movie is not “Kiribati is going under water so I should take action and buy a Tesla and it’s going to be better.” It’s way deeper than that. What we need now is a real paradigm shift. It’s a question of re-connecting to our land and the nature around us. And that’s something Tong is deeply concerned with. We are basically disconnected and the climate is in crisis.

Anote’s Ark is a quiet film with many meditative shots of water, as opposed to the dramatic floods shown in other climate change films. Why did you choose to make the film this way?

Because I respect nature. For me, the first director of this film is nature and the island itself. It has its own voice. Climate change movies in general are dramatic and fast and show destruction. It’s easy to show these powerful images. But they don’t resonate for me. For me, climate change is much more subtle. Like erosion. It takes time, but it’s happening. Take the example of Manhattan. Every day, every single day, some rock is worn away. It’s not dramatic. And it will eventually destroy everything. It’s deep and subtle and unstoppable.

Meanwhile, though, Kiribati has a new president who has undone many of Tong’s climate-oriented policies.

This new government doesn’t really believe that people of Kiribati will have to move away from the islands, but rather that God will eventually take care of them. I think they took that position to get elected. I went with my partner to Kiribati over Christmas, and I took my projector and my laptop and started showing the movie in different communities. The people loved the movie. But I was stopped by immigration and the police and they took my laptop and projector, and we were deported. I cannot go back now. But the thing is, when this happened the UN Ambassador from Kiribati in New York sent an official letter to the Sundance Film Festival, claiming the content movie was a lie. Obviously, Sundance didn't take this request into account and instead premiered the film.

How is Sermary now?

Sermary is good. The Kribati have such a powerful community, they just stay together and hang out together in Auckland. I was with them two weeks ago, and it was beautiful. It could be better of course, but they have a good life there. If I had scripted the movie, and said at the end, Sermary would have a baby in New Zealand, and we would film her saying to her baby, “Are you a Kiwi?” I would say it’s too much. But that happened. I didn’t want the movie to have a positive end, but it’s just life, and it goes on.

Is there anything else you’d like to say?

For me, the next question will be climate justice, and who has access to these funds and resources. Which is why this movie belongs in a human rights film festival.

You can see Anotes Ark at the Human Rights Watch Film Festival in NY June 15-18 https://ff.hrw.org/film/anotes-ark?city=New%20York

This interview has been edited and condensed.