(Geneva) – The United Nations Human Rights Council should renew the mandate for the Commission of Inquiry on Burundi during its ongoing session in Geneva. The commission is the strongest – and one of the few – sources of public reporting on the serious human rights abuses being committed in the country, including killings, beatings, sexual violence, arbitrary imprisonment, and intimidation.

Burundi has faced a political, human rights, and humanitarian crisis since April 2015, when President Pierre Nkurunziza decided to run for a disputed third term. A constitutional referendum was held on May 17, 2018 in the context of widespread ill-treatment by local authorities, the police, and members of the ruling party’s youth league, the Imbonerakure – with no consequences for the abuse. The referendum’s aftermath was marred by abuses against those who voted against the constitutional change or who were suspected of having instructed others to do so, Human Rights Watch research found in a series of new interviews with people who fled the country as a result.

“The human rights situation in Burundi will not improve until there is justice for past and ongoing crimes,” said Lewis Mudge, senior Africa researcher at Human Rights Watch. “Given the gravity and persistence of the abuses, it is vital to continue the Commission of Inquiry’s independent investigation to lay out the evidence of crimes committed by all parties.”

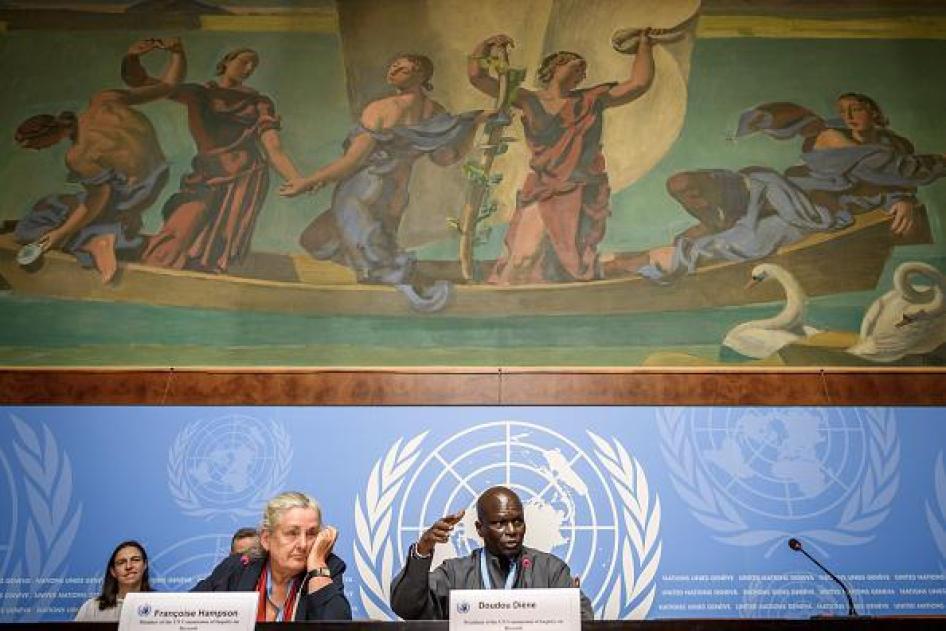

The Commission of Inquiry on Burundi was established in September 2016, with its mandate renewed in September 2017. The commission’s second report, on August 8, found that “the serious human rights violations documented in the first year of its mandate, including crimes against humanity, persisted in 2017 and 2018” and that most of the victims were opponents or perceived opponents of the ruling party, the National Council for the Defense of Democracy-Forces for the Defense of Democracy (CNDD-FDD). The commission also drew particular attention to the “growing role” of the Imbonerakure and the responsibility of the Burundian government for their abuses.

A comprehensive version of the report was released on September 12. The UN Human Rights Council will vote on the resolution for the Commission’s renewal on September 27 or 28.

In a report released in May, Human Rights Watch documented that state security services and Imbonerakure members had killed, raped, abducted, beat, and intimidated suspected opponents of the referendum earlier that month. In September, Human Rights Watch spoke with 20 Burundians in Uganda who had fled the country either just before or after the May referendum. They spoke of continued patterns of beatings, threats, and intimidation of those who voted against the constitutional change, or against those suspected of having instructed others to vote “no.”

“I had to leave after the referendum because I was a member of an opposition party,” a teacher from Rutana Province said. “After the referendum, Imbonerakure members and the local leaders approached me and said, ‘We know you told people to vote against the referendum. You will now see.’”

Police arrested the teacher on June 10. “As soon as I got to the police station, the police started to beat me,” he said. “They threw me to the ground and started kicking me and yelling, ‘You are in the FNL [National Liberation Forces, an opposition party]! You have defied the CNDD-FDD and now, whether you like it or not, we will show you who is the strongest.” After he was released, then re-arrested and beaten again, the teacher fled the country in late July.

Security services and the Imbonerakure have become more secretive, attempting to conceal many of their abuses, but remain just as brutal. This makes it difficult to confirm the full scale of the abuses.

The Burundian government denies that state agents are responsible for human rights violations, and the CNDD-FDD has also categorically rejected allegations that the Imbonerakure have committed abuses.

The commission’s latest report reinforces that the ruling party strongly influences the national justice system, which has not delivered credible justice for these crimes. The government has coopted the National Independent Human Rights Commission, a national monitoring body, which as a result of losing its independence was downgraded by the Sub-Committee on Accreditation of the Global Alliance of National Human Rights Institutions in February.

The government’s blatant disregard for human rights is further illustrated by its refusal to cooperate with human rights monitoring and investigation bodies and systems. In July 2016, a Burundian delegation failed to answer questions from the UN Committee against Torture. Since 2016 the government has refused to share information or cooperate with the Commission of Inquiry on Burundi – twice threatening legal action against its members. In 2016, the government blocked African Union observers from independently monitoring the human rights situation in Burundi. And in 2018, Burundi revoked the visas to visit the country for experts mandated by the Human Rights Council, even though Burundi had supported the resolution for their visit.

Nevertheless, the Commission of Inquiry has continued its important investigative and evidence-gathering work. Its work could be crucial in establishing command responsibility for serious crimes, including crimes against humanity, and could inform a future prosecutorial strategy, Human Rights Watch said.

In October 2017, the International Criminal Court authorized an investigation into crimes in Burundi since April 2015. A preliminary examination of the situation was opened in April 2016. Burundi withdrew from the court on October 27, 2017, but the court still has jurisdiction over crimes committed in Burundi before that date.

The UN Security Council should draw on the findings of the Commission of Inquiry and impose targeted sanctions against those most responsible for serious crimes in Burundi.

“Burundian authorities’ disdain for the Commission of Inquiry should not dissuade the Human Rights Council from ensuring that the commission’s work continues,” Mudge said. “Those responsible for the ongoing serious crimes in Burundi need to know that the world is watching and they will one day be held to account.”

Turmoil in Burundi

While Nkurunziza’s third, and current term was disputed, the former constitution clearly did not permit a fourth. The president and his party called for a referendum to change the constitution, which passed. The changes increased presidential terms from five to seven years, renewable only once. However, the clock on terms already served was also reset, so Nkurunziza could run for two new seven-year terms, one in 2020 and another in 2027, allowing him to potentially extend his rule until 2034.

Human rights violations and abusive tactics by state and ruling party agents escalated following a failed coup d’état in May 2015, soon after Nkurunziza announced his bid to run for a controversial third term.

Since then, state security services and members of the Imbonerakure have killed, tortured, raped, arrested, beaten, and intimidated members of political opposition parties and others perceived as being against the government.

New Abuse After the Referendum

In September, Human Rights Watch interviewed 20 people who fled Burundi just before or after the May 17 referendum. They all described a climate of fear, which led them to flee the country and said that they were threatened, intimidated, beaten, arrested, or faced other reprisals because they were known or suspected of having voted against the referendum, or of instructing others to do so.

A farmer from Rumonge Province, who arrived in Uganda on September 11, said that he received messages from the Imbonerakure starting on May 17 telling him he was going to be killed. “This question of who voted ‘yes’ and who voted ‘no’ to the change has made it obvious as to where people stand with the government,” he said. “If you are not for the CNDD-FDD, you are in real danger. I voted ‘no’ [and] the Imbonerakure found out somehow. I got a message from a friend close to the Imbonerakure saying, ‘They know you voted ‘no’ and they are going to kill you because you are not with them. You must flee now.’”

A 37-year-old farmer who fled Kirundo Province in July said:

The day after the vote, the Imbonerakure came to my house and said, “How can you tell people to vote ‘no’ when this country has the CNDD-FDD, a party that works so hard?” I told them, “People can vote how they want.” One Imbonerakure said, “Ok, you have gone against the CNDD-FDD and now you will see the consequences.” For the next two months I was threatened repeatedly by the Imbonerakure. Then, in July, I was arrested by intelligence agents. They locked me up and said, “Why don’t you admit that you are against the country and that you encouraged people to vote against us?” I fled at the next opportunity.

People who refused to participate in CNDD-FDD campaigns for the referendum were singled out after the vote. A 27-year-old student from Bujumbura said. “When I refused to help the CNDD-FDD instruct people to vote ‘yes,’ the Imbonerakure started paying attention to me,” he said. After the vote, an Imbonerakure member told the student, “We asked you to help us and you refused. Now we know you are ibipinga [a traitor, in the Kirundi language], and we will deal with you.” The student fled Burundi on May 19.

Two recent refugees said that people in Burundi with family outside the country were particularly targeted. “My family had already fled to Rwanda, and I was receiving threats from the Imbonerakure,” said a 54-year-old businessman from Bujumbura. “After the referendum, the Imbonerakure could do what they want. You can’t have an opinion that goes against the CNDD-FDD. I was threatened, and I had no choice. The Imbonerakure are more powerful than the police.” He fled the country in late May.

Two men who fled in July said that Imbonerakure members knew they had voted no. One, a 43-year-old man, said that Imbonerakure members approached him just after he voted in Karusi Province:

An Imbonerakure walked up to me and said, “Why did you vote ‘no’?” I said, “How do you know I voted ‘no’? He told me that he had people watching me. I said, “What is done is done; I have made my choice.” The Imbonerakure told me, “You made a mistake. Now we know you are really against us. Now you will see how you will pay for what you have done.”

I was then careful with my movements. But in late May, a local official called me and said, “Do you really think the CNDD-FDD can ever lose? If you don’t want the CNDD-FDD to win, then you should just disappear.” He told me I was considered an enemy of the state because I voted ‘no.’ I went home and prepared some money to escape the country. In Burundi, if you don’t accept the CNDD-FDD, then you really have problems.