Chinese authorities are requiring key Tibetan monks and nuns to act as propagandists for the government and Communist Party, Human Rights Watch said today. Under new policies for “Sinicizing” religion, the government has been compelling selected monastics in the Tibetan Autonomous Region (TAR) to undergo political training designed to create a new corps of Buddhist teachers proficient in state ideology.

Under the “Four Standards” policy introduced in TAR in 2018, monks and nuns must demonstrate – apart from competence in Buddhist studies – “political reliability,” “moral integrity capable of impressing the public,” and willingness to “play an active role at critical moments.” The implication is that they must agree to forestall or stop any attempts to protest state policy.

“Chinese authorities have always placed heavy constraints on religious freedom, especially in Tibetan and other minority regions,” said Sophie Richardson, China director at Human Rights Watch. “Compelling Tibetan monks and nuns to be propagandists for the Communist Party takes government intrusion in religion to abhorrent new levels.”

The “Four Standards” policy followed September 2017 revisions to the 2005 Regulations on Religious Affairs and is based on ideas discussed at the national-level Conference on Religion Work in April 2016. A select group of Tibetan monks and nuns attended a three-day training session, from May 31 to June 2, “to strengthen their political beliefs,” state media said, and to prepare them to conduct the campaign in their own monasteries and communities. The number of participants was not revealed, but a political training course for Tibetan monks and nuns in September 2016, which appears to have been a pilot program, involved 250 participants. Monks with outstanding religious knowledge were selected for the training, and it is unlikely that they could refuse to participate. Those who meet the “Four Standards” are rewarded with benefits and status but required to work actively as political educators.

A recent Global Times report describes the trainees with a term generally used for local officials responsible for relaying party and government policies and propaganda at the grassroots level (Ch: Xuanjiangyuan/Tib: sGrog ’grel pa). This indicates that the government has broadened the term to cover monks and nuns selected on the basis of political reliability. Recruiting monastics to promote the party and government is more effective, according to Xiong Kunxin, the expert the Global Times quoted, because “they have a better understanding of the thoughts and habits of their own group.”

In 2012, the government established an elite Tibetan Buddhism Higher Studies Institute to train select monks and nuns from across the Tibet Autonomous Region, and other provinces with Tibetan populations have established similar institutes. These are designed to produce a new generation of “patriotic religious professionals,” teachers qualified both in religious studies and commitment to the party’s ideology and mission. The formulation suggests that previous attempts at political indoctrination in monasteries, led by Party cadres, have been insufficient, and that the lack of credible Tibetan religious figures promoting the Party in the region has been identified as a long-term problem.

Previous Attempts

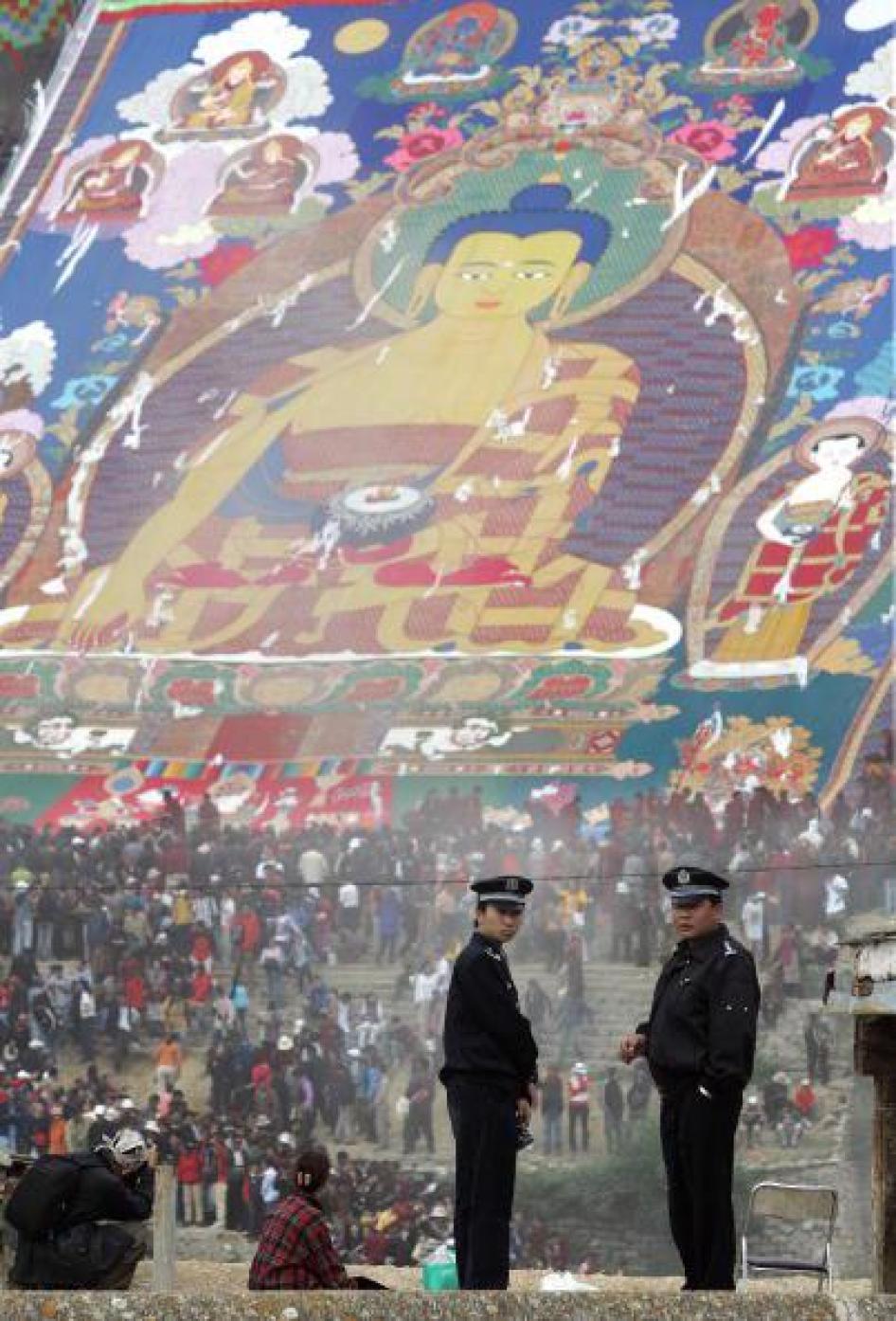

The Communist Party has spent years trying to “correct” the thinking of Tibetan monks and nuns, using party members and officials to carry out political reeducation. In May 1996, the party sent work teams to each monastery in the TAR, usually for three months at a time, to carry out repeated rounds of “patriotic education.” These training sessions, which continued over 15 years, required all monks and nuns to denounce the exiled Tibetan leader, the Dalai Lama, on pain of expulsion from their religious communities.

In October 2011, party leaders in the TAR launched a new strategy: they moved teams of 7,000 professional Party cadres to live permanently in each monastery in the region to take over the direct management of the monasteries and reeducate the monks.

In 2012, the then-party secretary of the TAR, Chen Quanguo, initiated a secret program of arbitrarily detaining Tibetans who had attended teachings by the exiled Dalai Lama in India, holding them in undisclosed detention centers for three to six months, during with they were given political education.

In 2013, Chen said, “We will actively promote socialist core values in government institutions, enterprises, villages, local communities, schools, military camps, and monasteries so that the core values will deeply take root in the minds of people of different ethnic groups in the entire Autonomous Region.” The 12 “socialist core values” include harmony, civility, democracy, rule of law, and justice. However, only the ninth value – aiguo, or patriotism – is emphasized in standard political education materials for Tibetan monastics.

Sinicization

The Chinese government’s current propaganda strategy is part of the national-level “Sinicization of religion” policy approved during President Xi Jinping’s first term, involving enhanced intervention by Party and government officials in the “management” of religious institutions.

The policy allows authorities to reshape the content of religious doctrine itself based on compatibility with “socialist core values.” The 2015 meeting, for example, discussed “building a group of learned persons versed in the new formulation, encouraging research in canonical knowledge and alternative uses of the outcomes of canonical knowledge, establishing characteristic forms of instruction, and introducing written forms of the new interpretation.”

A senior United Front official, Zhu Weiqun, described this as “the third level of adapting religion to socialism,” which “requires religious circles to further excavate and carry forward [Ch.: wajue he hongyang] content within their doctrines and canons which is beneficial to national development, social stability, and promoting morality. Historically, religious classics and the doctrines and canons cannot be altered from how they were passed down, but new interpretations can be made which integrate the requirements of the age and provide new content.”

One example of this determination to reformulate Tibetan Buddhist tradition based on government ideology is the increasing practice of excluding teachers trained outside China. The Chinese authorities banned a monastic program within the TAR to train Tibetan monks for the Geshe degree – the highest academic qualification in Tibetan Buddhism – in 1988, but more recently established a state-run academic program administered by the Chinese Buddhist Association to produce Tibetan monks with this degree.

As a result, the authorities are now excluding Geshes qualified at exile monasteries in India from teaching positions at monasteries in Tibet. State media reports that “politics, law, and history” tests are a mandatory part of the officially administered Geshe degree.

Doctrinal reformulation is now being applied to all organized religions in China, but the political imperative is strongest in the Tibetan and Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Regions, where the Party considers religious identity a threat to national integration.

“Authorities’ injection of political dogma into religious curriculum and new requirements that monastics indoctrinate one another reflect Beijing’s hostility to the freedom of religious belief,” Richardson said.