How was this project conceived?

Years of our research has shown that businesses operating in Israeli settlements in the occupied West Bank both benefit from and contribute to serious violations of international law and human rights. We published a report in 2016 called “Occupation Inc.,” where we concluded that operating in settlements goes against a company’s human rights responsibilities. Settlements violate the laws of occupation and are built on land that rightfully belongs to Palestinians. The Israeli military effectively bars Palestinian ID holders from staying in settlements, restricts their movement in much of the West Bank while settlers can move about freely in these areas and grants settlers permits to build in the areas of the West Bank under full Israeli control while rarely granting such permits to Palestinian residents. Israel discriminates in favor of settlements and against Palestinians in the provision of infrastructure, water and other resources. Business activity in settlements entrenches this unlawful and discriminatory system.

What led to Airbnb’s announcement that it would remove from its website all properties in Israeli settlements in the West Bank?

Airbnb’s brokering of rentals in settlements on land unlawfully seized from Palestinians is at odds with its progressive anti-discrimination policy in the United States and Europe – especially considering that local Palestinians can’t even stay in these rentals should they want to. Airbnb’s decision was the only way it could adhere to its human rights responsibilities.

A range of groups have raised concerns about Airbnb’s settlement listings going back years. We have been engaging Airbnb’s Global Policy Team for two years. When it appeared that Airbnb was unlikely to change its policy, we began researching these issues on the ground early this year. We spoke to them several times in 2018, including just after they announced they would remove these listings.

Who conducted this research?

Our small research team on the ground primarily. Our team includes a colleague who holds a Palestinian ID, so is effectively barred from entering the settlements, but is able to go to nearby Palestinian villages and speak to local officials and landowners, and a colleague who holds Israeli ID and speaks Hebrew, who is able to go into settlements and engage hosts.

How did you research this project?

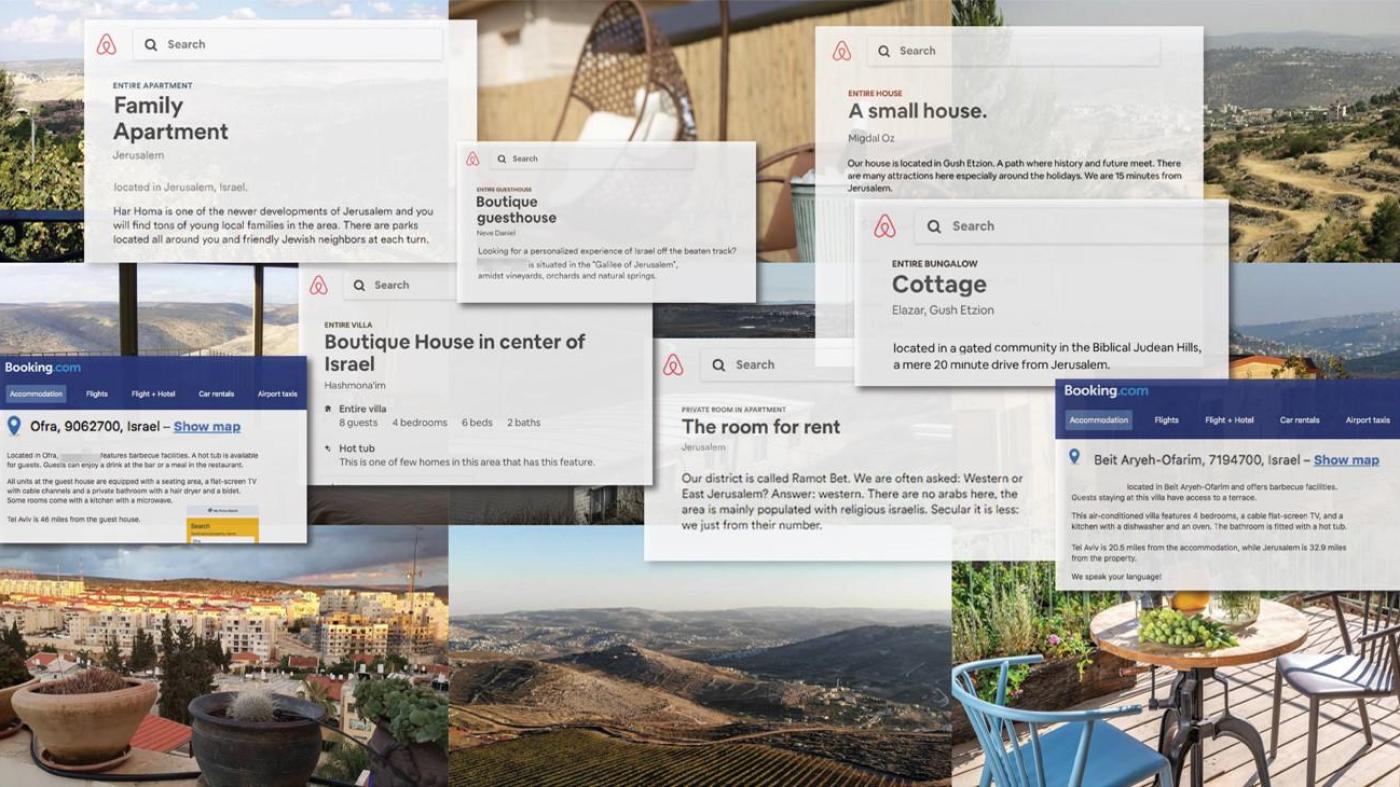

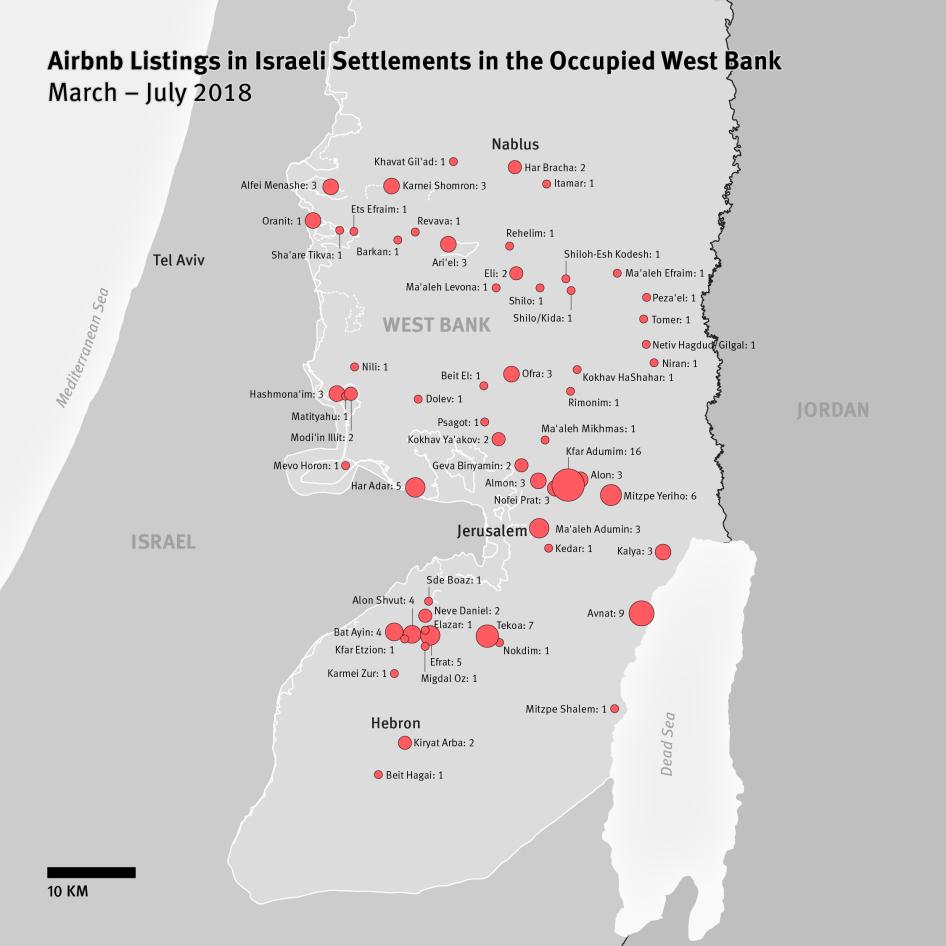

We began by reviewing online listings on Airbnb and Booking.com. We cross-checked listings on different sites, because some sites provide more specific addresses than others. We conducted site visits to certain settlements, and in many cases, we made inquiries directly to the hosts on the Airbnb platform. The first step was to identify exactly where these listings were located. Our research found 139 Airbnb listings and 26 Booking.com listings in illegal settlements in the West Bank.

Then, we worked with the Israeli organization Kerem Navot to review land status data they obtained from the Israeli Civil Administration, which is the branch of the Israeli military in charge of civilian affairs in the West Bank. We reviewed the data to determine the status of the land on which many of the properties are located – whether the Israeli army considers the land to be privately owned by Palestinians, or “state land.”

We visited several of the Airbnb properties, and we also sought comment from Airbnb hosts. We went to the Palestinian villages adjacent to the settlements to review Palestinian records on land ownership. We spoke to officials from local Palestinian municipalities, we reviewed the land records, and if we found that the parcel of land on which the Airbnb property is located was privately owned Palestinian land, we would ask for the landowner’s contact information. In many cases, municipalities have that information. We interviewed several residents whose land was taken over by settlements.

Some Palestinian landowners didn’t know their properties were being rented out, right?

Exactly. In many cases, the Israeli army or groups of settlers seized their land years ago and, since then, settlers have built properties that they rent out on Airbnb and Booking.com. The Palestinian landowners certainly did not consent to their property being used in this way, they do not share in the rental profits, and they cannot access that land, even if they pay to stay at an Airbnb located on their own property. The Israeli government even acknowledges that some of this land is privately owned by the Palestinians.

What were the Palestinians’ reactions when they found out their properties were being rented out?

One landowner told us, “For someone to occupy your land, that’s illegal. For someone to build on your land, to rent it out, and to profit from it – that’s injustice itself.” Not only has their property been taken over, but now it’s being advertised for rent and hosts are welcoming guests from around the world – except if you hold a Palestinian ID. It really adds insult to injury.

What means are used to prevent Palestinian landowners from accessing their land?

At first, the army seized land – including private land – ostensibly for military purposes, then repurposed it for use by Israeli civilians. After a 1979 court banning this practice, it began to turn over what it considers to be state land to settlements, but it makes that determination based on laws that date back to the Ottoman period that only recognizes a subset of land claims. And then there are cases where Israeli settlers seize land owned by Palestinians, and eventually the Israeli government provides it with services and infrastructure. Many Palestinians also own land around settlements that they can access only a few times a year.

There are different methods used, but the result the same: land gated off for use by Israeli Jews and off-limits to Palestinians.

Can you share any of the experiences that Palestinian landowners shared with you?

One of the Palestinian landowners we met is Awni Shaaeb. He is a 70-year-old resident of Ein Yabroud, a Palestinian village in the center of the West Bank near Ramallah. He is a US citizen and served in the US Army years ago. He lived in New York for 15 years and Puerto Rico for 17 years. He moved back to the West Bank after the death of his father. He owns a parcel of land on which an Airbnb is listed. In 1975, Israeli settlers seized the farmlands of Ein Yabroud to establish the Ofra settlement, which is there now. We reviewed a 1986 title deed issued by the Israeli Civil Administration listing his family as the owner of the land in question. He lost access to the land beginning in the 1990s, he said. The authorities built a highway through his land in 1994, and they later built a fence between the villagers’ houses and the farmland. Soldiers began demanding permits of Palestinians to enter the land and sometimes they declared it to be a closed military zone. He’s been turned away numerous times trying to get to his land, as a military order effectively bars Palestinian ID holders from entering Ofra and other West Bank settlements.

We contacted the owner of the property on Awni’s land using the Airbnb platform, but the host did not respond. We looked at aerial photos taken over 18 years that show the property in question was built in 2006 or 2007 as part of an expansion of the settlement. The Airbnb listing for the property, as of September 2018, states that it is located in “Jerusalem, Jerusalem District, Israel,” which is false.

You spoke to hosts as well?

We reached out to a number of hosts on the Airbnb platform, and a Human Rights Watch staffer stayed at a listing and was able to interview a host. That Airbnb host claimed his house wasn’t built on privately owned Palestinian land, but our research shows that there is no way for him to know for sure because the Israeli army doesn’t always recognize traditional land titles when it designates land as belonging to the state, and then allows settlers to build on it. But regardless of whether the land was privately owned, the host isn’t allowed to live there – let alone rent out his place for profit – under the laws of occupation.

Your research also found listings in illegal settlements in the West Bank on Booking.com. How did they respond?

Booking.com denied that it should be considered as doing business in settlements, explaining that it neither buys nor sells anything but rather serves as a platform for transactions. But facilitating the rental of properties in settlements obviously does constitute doing business. Booking.com is contributing to the financial sustainability of settlements, supporting their maintenance and their existence, and contributing to the perception of their legitimacy despite their unlawfulness.

What should Booking.com and other businesses operating in settlements do?

To comply with their responsibilities under the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, Booking.com should stop listing properties in settlements.

Israeli officials and some supporters say that Airbnb is unfairly singling out Israel with its decision, as it also has listings in other occupied territories, like Western Sahara. How would you respond to this?

In our report, we recommended that Airbnb create a universal policy for doing business in situations of occupation. Airbnb has stated that it is delisting settlement properties as a first step in implementing a new policy toward occupied territories that includes assessing whether the listings contribute to “existing human suffering.”

Each occupation has its specific characteristics and human rights problems. In the West Bank, Israel has built illegal settlements on land taken from Palestinians who cannot themselves stay there, making peer-to-peer booking platforms like Airbnb complicit in discrimination against a people in their own homeland. Western Sahara, for example, has a raft of human rights problems, but no law prevents native Sahrawis from renting at a Moroccan-owned Airbnb.

Settlements are a clear-cut case for Airbnb and a suitable place to start in implementing a universal policy.