What’s happening in northern Myanmar?

There’s a long-running conflict between Myanmar’s government and the Kachin Independence Army and other ethnic armed groups in Kachin State and northern Shan State, which border China. In 2011, the military renewed attacks against the ethnic armed groups, ending a 17-year ceasefire. This has led to over 100,000 displaced Kachin and other minorities living in camps, including many of the trafficked women we met.

How are women being trafficked to China?

Many Kachin men are taking part in the conflict, so women often become the sole breadwinners. There’s also a cultural expectation that eldest daughters support the family financially. There is an intense level of financial desperation in the camps, as people there can’t find work and the Myanmar government has blocked aid deliveries. Yet the camps are close to the Chinese border, which is easy to cross without a passport.

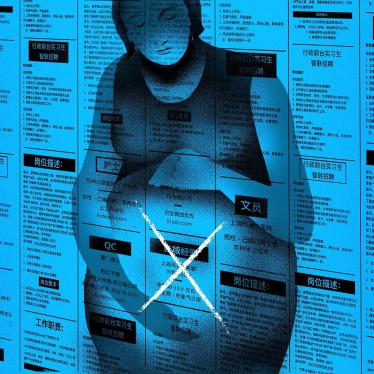

Plenty of employers in China are willing to hire people from Myanmar, and this situation creates a huge opportunity for traffickers. Usually, someone in Myanmar tells a woman that they know a farm or a restaurant that needs workers. Often, these jobs are real, but sometimes they’re not. Most of the 37 women and girls we interviewed accepted these types of jobs. But the people who recruited them turned out to be traffickers who sold them to Chinese families.

Why are Chinese families buying women from Myanmar?

There’s a serious gender imbalance in China, driven in large part by the one-child policy. From 1979 to 2015, China only allowed most families to have one child. In many Chinese communities, sons traditionally stay with their parents and support them in old age while daughters live with their husband and in-laws, creating an incentive to ensure that your only child is a son. Today there are 30 to 40 million more men than women in China. So many men have had a hard time finding wives, creating a demand for trafficked “brides.”

Who are these traffickers?

Our research found that the traffickers are almost never strangers. One was a friend a woman had met at Bible study class. And in a significant number of cases, a family member – an aunt or cousin – recruited and sold the woman.

Prices ranged from US$3,000 to $13,000, people told us. That money goes to the traffickers. One man likened it to trading jade: “If jade is a good quality we make a call and trade from one broker to another. Same thing with a girl, traded from one broker to another.”

What happens to the women and girls?

The person who has recruited them escorts them to China. Quite a few were drugged during the journey and woke up in a locked room across the border. A pretty typical story is that of a young woman whose sister-in-law said she could get her a well-paid job in China. The young woman didn’t want to go, but her family needed the money. In the car on the way to China, her sister-in-law gave her medicine she said was for car sickness. She woke up with her hands tied, and her sister-in-law later told her she had to get married and left her at her buyer’s home. The family took her to a room, where she was tied up again. Each time her “husband” brought her meals, he raped her. She eventually had a son. Two years later, she escaped with her son. The most unusual part of her story is that she was able to escape without having to leave her child behind.

Most of the women and girls we interviewed were locked in a room for days or weeks or months, sometimes until they became pregnant. Many said that the families seem more interested in having a baby than a bride. Some were able to escape after they’d had a child, or were even told they could leave if they wanted. The 37 women and girls we spoke with had all escaped and made it back to Myanmar.

Is the number of trafficking cases increasing or decreasing?

It’s difficult to know how many women and girls are trafficked to China each year. The Myanmar Human Rights Commission told us they had data on 226 cases in 2017 from the immigration authorities, but almost none of the women we interviewed had come to immigration’s attention. The real number is certainly much higher. It is also hard to know whether the number is going up or down, but several experts said they believe the number is going up as the conflict in Kachin State continues.

You’ve said this is one of the most difficult projects you’ve worked on. What made this research particularly difficult?

We started this research almost three years ago. It was really hard to find these women, and difficult to make people feel comfortable talking about this. Most ethnic Kachin are Christian, and many are deeply religious. There’s a lot of stigma against sex outside of marriage. There are a lot of reasons for people to keep these experiences a secret. There are also serious security challenges related to the ongoing fighting.

We were lucky to have help from people who were trusted in the camps, and we worked with a great consultant who was knowledgeable about Kachin State. We worked hard to find ways to interview survivors that honored their safety and confidentiality. These women and girls had been through so much, but they were also often very determined to try to prevent this from happening to others.

What do women and girls face once they’ve returned home?

Some manage to escape China after a few weeks or months, but some were held for years – one for 9 years. Twelve were under 18, the youngest 14. And two people had been trafficked twice.

One woman said she made it to the Chinese police, who deported her, leaving her stranded at the border with no money. She begged a taxi driver to take her to her family’s home, not knowing if they were still there since she’d been gone for five or six years.

Some of their families were wonderfully supportive and desperately happy to have them back. But the broader community is not, and even within families, survivors sometimes found themselves blamed and judged. Some survivors were so overwhelmed by stigma that they left their communities. We heard secondhand stories of women and girls who felt, out of shame, that they had no choice but to stay in China.

One woman described coming home to her husband after she went to China to work and was trafficked instead. He said she shouldn’t tell anyone because “people might look down on you because you were trafficked to China.”

Government services for trafficking survivors – provided to a scant 100-or-so people per year – primarily consist of providing shelter for a few days, a medical examination, and a new ID card, with smaller number receiving limited financial or vocational assistance. There are civil society organizations working to rescue women, but these organizations get very little funding.

How have Chinese and Myanmar authorities responded?

Trafficking is illegal in both countries, and there are some attempts on both sides to stop trafficking. But most of our interviewees escaped on their own, and we heard a lot of stories of police on both sides of the border being complicit in trafficking, even benefitting financially. We heard from families who went to the Myanmar police over and over, including the anti-trafficking police, and they wouldn’t do anything. The Chinese police took little action against the traffickers and often treated the women and girls as violators of immigration law. In one case we learned about, the Chinese police demanded a US$800 bribe from the family the woman had escaped from and then handed her back to them.

What has really stayed with you in this lengthy reporting process?

There were stories of amazingly courageous women who escaped in ingenious ways. One young woman who was trafficked at 17 tricked her “husband” into giving her a cell phone and used WeChat to post messages on Kachin notice boards. Suddenly people all over the world, including in the US, were trying to help find her. The man realized what was happening and took the phone away, but became worried when he realized all these people were looking for him. The family ended up just letting her go. That was one uplifting thing about these stories, the resilience and ingenuity in the most horrific situations.

![“Because of war, we are afraid to stay in our village. So, we moved to an IDP [internally displaced person] camp…The Myanmar army came to attack our village using massive arms…I am the eldest one in my family, and my family has financial problems.](/sites/default/files/styles/16x9_xxl/public/multimedia_images_2019/201903wrd_myanmar_photo4_0.jpg?itok=AyFa_Tfx)

![“Then the Chinese man said, ‘If you do not marry a man, the money we spent on you to bring you here…was 3000 Yuan and as you have already stayed here for 10 days, 4000 Yuan [US$637] is needed to give me back now. Right now, count the money to give me.](/sites/default/files/styles/embed_xxl/public/multimedia_images_2019/201903wrd_myanmar_photo5.jpg?itok=pHIMT_m9)