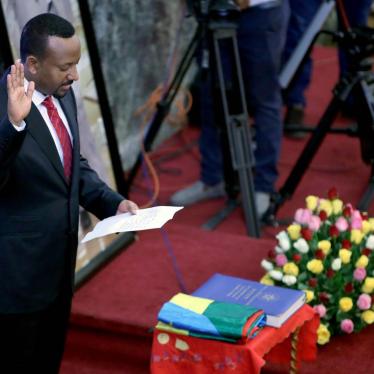

One year ago this month, Dr. Abiy Ahmed was sworn in as prime minister of Ethiopia. His first few months in office saw many positive human rights reforms and a renewed sense of optimism following several years of protests and instability, along with decades of repressive authoritarian rule. Thousands of political prisoners have been released, a peace agreement has been signed with neighboring Eritrea, and Abiy has pledged to reform repressive laws. But in the months that followed, growing tensions and conflicts, largely along ethnic lines, have resulted in significant displacement and a breakdown in law and order across much of the country, threatening progress on key reforms.

This week we will publish a series of assessments of Prime Minister Abiy’s first year in office, looking at his government’s performance regarding eight key human rights priorities and providing recommendations on what more needs to be done in his second year in office, leading up to elections scheduled for May 2020.

Today, in Part 1 of 8, we look at the government’s performance on Freedom of Assembly, including protest-related abuses.

Freedom of Assembly

Background

The use of excessive force by security forces in response to peaceful protests is a long-standing problem in Ethiopia.

Most recently, in November 2015, protests began in Ginchi, Oromia region. Subsequent protests took place in hundreds of locations across all 17 zones in Oromia over the following three years. Protesters were initially concerned about the federal government’s proposed expansion of the capital, Addis Ababa, that would potentially led to the further displacement of Oromo farmers.

During the protests, state security forces shot into crowds, conducted mass arrests, and tortured detained protesters. During the October 2016 Irreecha Oromo cultural festival, hundreds died following a stampede triggered by security forces’ use of teargas and use of live ammunition . In total, more than 1,000 civilians were killed in the unrest between 2015 and early 2018.

Two states of emergency occurred during the crackdowns: one from October 2016 to August 2017 and another beginning in February 2018, which was intended to last six months. Security forces arrested more than 20,000 people during the first state of emergency and banned all public protests not approved by the government. The government gave the army standing permission to enter schools and universities to make arrests, search houses without a warrant, and ban “stay at home” strikes, the closing of shops, and roadblocks. Under Ethiopian law, permits are required for protests although in practice, especially outside of Addis, protests occur without permits.

Under Abiy

Abiy was ushered into power in April 2018 in large part due to the efforts of protesters demanding change and respect for their rights. In June 2018, he ended the state of emergency after four months, effectively lifting the ban on protests.

During Prime Minister Abiy’s first year, there have been fewer protests, and most protests that did take place occurred without excessive force being used by security forces. However, there have been occasions when federal or regional security forces may have used excessive force including around Shakiso, Oromia in May, in and around Raya in October, and in Dire Dawa in January. In one of the worst cases, clashes broke out during protests in and around Burayu in September, fueled in part by the return of some exiled politicians. At least 23 people were killed in the violence and security forces killed several more during a subsequent demonstration.

Permits continue to be routinely denied for protests or public gatherings to occur in Addis Ababa.

There has still been no adequate, let alone independent, investigation into abuses committed by security forces during the 2014 to 2018 protests. No one has been held to account for these abuses.

What more can be done

Permits should not be unduly denied for protests or public gatherings. Security forces responsible for using excessive force should be held to account, regardless of their rank or government position. Prime Minister Abiy should publicly reaffirm that people have the right to peacefully protest. Appropriate training should be given for all security forces involved in crowd control, including regional and local security forces.