(Goma) – A Congolese military court’s conviction of a warlord for the war crimes of rape and use of child soldiers in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo showed serious shortcomings in the country’s military justice system. The 15-year prison sentence for Marcel Habarugira provides a measure of justice for his victims and may serve as a check on other abusive commanders. However, the trial proceedings raised questions about witness protection, the defendant’s right to an appeal, and the government’s failure to pay reparations to victims.

On February 1, 2019, a military court in Goma, North Kivu province, found Habarugira, a former Congolese army soldier, guilty of three crimes committed while leading a faction of an armed group known as Nyatura (“hit hard” in Kinyarwanda). The group, which received arms and training from the Congolese army, carried out many of its worst attacks in 2012.

“The conviction of a warlord for war crimes is a rare event in Congo, and the vast majority of abusive military commanders remain at large,” said Timo Mueller, Congo researcher at Human Rights Watch. “However, the trial of Habarugira for rape and use of child soldiers uncovered serious flaws in Congo’s military justice system.”

Human Rights Watch worked with a local rights defender to monitor the three-month trial and spoke to survivors of abuses, legal counsel, judicial officers, United Nations officials, and members of domestic and international nongovernmental organizations. Human Rights Watch secured a copy of the written judgment in mid-March. In 2013, Human Rights Watch interviewed victims, Nyatura fighters, and Congolese army personnel during three visits to Masisi, North Kivu.

Lack of protection for victims and witnesses undercut the prosecution’s case, Human Rights Watch said. Military justice officials interviewed over 100 victims and witnesses who traveled unobtrusively from villages across North Kivu. Yet many who wanted to testify were unable to travel due to obstruction, threats, and intimidation by Habarugira’s fighters and ethnic Hutu youth loyal to the group.

Victims from Katoyi and Ngungu told Human Rights Watch in 2015 that Habarugira’s fighters told them they would be killed if they went to testify against him. A year later, Congolese intelligence agents and local Hutu youth in Ngungu beat and detained for several hours a local human rights activist who had facilitated the participation of victims in the trial proceedings. In 2018, groups of Hutu youth blocked the roads to stop victims from Katoyi who attempted to make the trip.

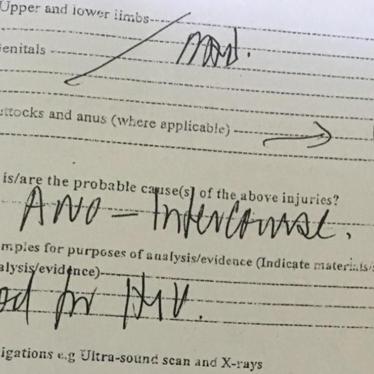

Only seven victims participated in the trial. Notably, no witnesses came forward with respect to the charge of sexual slavery as a war crime, and Habarugira was acquitted on this charge.

“When I arrived in Bweremana to testify, I found Habarugira’s collaborators there,” said a man who had been forcibly recruited. “I recognized one of them. He approached me and said he would give me money if I didn’t testify against Habarugira. I accepted because, if I didn’t accept, how would I go back home? These are people who live with us. They’re the ones in charge where we live.”

A woman who had been raped by Habarugira’s fighters said that she knew many other victims who did not come to testify because they had heard that Habarugira’s fighters “were waiting for them along the road to do bad things to them.”

Four years after his arrest in 2014, Habarugira was tried by a Congolese military court that normally tries soldiers immediately for crimes committed during military operations. It does not allow for the right to appeal, contrary to the Congolese constitution and international fair trial standards.

Seventeen victims and victims’ family members filed a civil suit alongside the criminal proceedings and were awarded US$5,000 each, to be paid for by Habarugira and the Congolese government due to Habarugira’s former position in the army. While Congolese courts have often awarded reparations to victims of sexual violence and other serious crimes, these reparations have rarely – if ever – been paid. The Congolese government should immediately pay the reparations ordered from the government in this case and develop an effective and sustainable reparations system for grave international crimes, Human Rights Watch said.

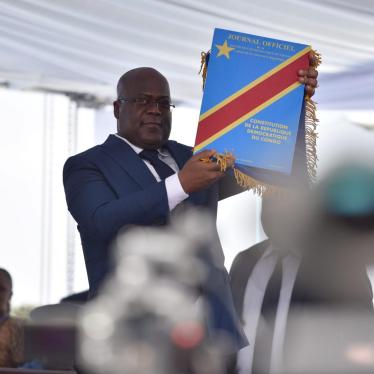

Habarugira’s conviction provides an opportunity for Congo’s new president, Felix Tshisekedi, and his administration to end the army’s practice of supporting armed groups such as the Nyatura by investigating and fairly prosecuting those responsible for serious crimes, Human Rights Watch said.

“To end the bloody cycles of violence and abuse in eastern Congo, armed group commanders responsible for abuses and their backers need to be held to account,” Mueller said. “But for justice to be meaningful, victims and witnesses need protection, and the fair trial rights of the accused must be respected.”

Marcel Habarugira

In the late 1990s, Habarugira was a low-ranking soldier in the Congolese Rally for Democracy (Rassemblement congolais pour la démocratie, RCD), a Rwandan-backed rebel group. He later joined the National Congress for the Defense of the People (Congrès national pour la défense du peuple, CNDP), another Rwandan-backed rebel group.

Habarugira eventually deserted the CNDP and joined the Congolese Patriotic Resistance, (Patriotes Résistants Congolais, or PARECO), a largely Hutu self-defense group. After a March 23, 2009 agreement in which CNDP and PARECO fighters were integrated into the Congolese army, he joined the army.

When many of the Hutu soldiers deserted in 2010 and 2011 in the face of their perceived marginalization by the army, Habarugira was among them. He formed his own fighting group, called Nyatura.

The Nyatura

While many of the fighting groups formed by the former Hutu soldiers have their own individual names or are named after their commanders, they are often referred to collectively as the Nyatura. The Nyatura have primarily attacked ethnic Tembo, Nyanga, and Hunde civilians over the years.

Habarugira’s troops were responsible for many of the worst attacks on civilians in southern North Kivu and parts of South Kivu provinces in 2012. Together with another Hutu group, the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR), Nyatura fighters summarily executed civilians, raped scores of women and girls, and burned down hundreds of homes in an apparent effort to “punish” civilians accused of supporting or collaborating with the “enemy.”

Many Nyatura groups have also collaborated with the army, including during military operations in 2012 and 2013 against the M23, a rebel group headed by Bosco Ntaganda, a former army commander now on trial in The Hague. According to the UN Group of Experts, the former chief of land forces, Gen. Gabriel Amisi (also known as “Tango Four”), who is currently the deputy chief of staff of the army, ordered army units in the area to work with the Nyatura, and sent them weapons in July 2012. Between September and November 2012, Habarugira, along with hundreds of Nyatura fighters went to a regroupment site in Mushaki, Masisi territory, where they were told they would be integrated into an army unit that would be called “Regiment Tango Four.”

Frustrated at the lack of progress, however, at least 600 of these fighters, including Habarugira, left the site about three months later. In an interview with Human Rights Watch in November 2013, Habarugira said he had received weapons – including mortars, rocket-propelled grenades, and bullets – from the army on November 12, 2012. Human Rights Watch saw an army document signed by a brigade general confirming this.

From early 2012 until the defeat of the M23 in early November 2013, Hutu militia groups operated in many parts of Masisi and Rutshuru territories where Congolese government and military authorities were largely absent. Nyatura leaders often took over administrative structures, displacing by force or sometimes coopting local government officials. Habarugira’s Nyatura joined forces with the Congolese army to fight the M23. They committed widespread abuses against civilians in the areas they controlled, including rape, torture, illegal detention, and looting.

Killings, Rapes, and Burning of Homes by Nyatura Fighters

Many of the worst attacks by Nyatura fighters took place between April and November 2012 during operations against the Raia Mutomboki, another armed group in the region, and their allies.

A 25-year-old ethnic Tembo woman from Ufamandu I groupement in southern Masisi told Human Rights Watch that she fled her village when Nyatura fighters attacked it on July 15, 2012. “When I was fleeing, I had to jump over the bodies of several people who had been killed – men, women, and children,” she said. “I don’t know how many because I myself was like a dead person.”

The woman took her children to hide into the surrounding forest with another group. “There were eight of us, all women,” she said. “Suddenly, we saw 10 fighters armed with machetes and knives coming toward us. They told us to lie down on the ground. We did, and then they started to rape us. Personally, I was raped by two fighters.”

Another Tembo woman from Ufamandu I in Masisi territory said that five Nyatura fighters raped her in July 2012:

I was asleep with my husband and children when the fighters broke into our home. When they saw me, they immediately started raping me, one after another. When the third one wanted to get on top of me, my husband came out of the corner where he was watching what was happening and shouted, ‘Enough is enough. This time, I’m not going to stand for any more of this!’ Without waiting, the fighters immediately shot him, and my husband died there on the floor in front of me. I was very afraid and started screaming at the top of my lungs. I was crying for my dear husband who was dead. A neighbor heard my screams and came to help, but he too was shot dead. I can’t return home today because we’ve learned that others who have gone back to our village to look for food were attacked again, some women raped, and others were killed.

On August 9, 2012, the Nyatura attacked Kipopo village, killing five civilians and burning dozens of homes. A 25-year-old pregnant mother of five said:

When they came, I was sleeping in my house. It was luck that saved me. My father said: “My daughter, you can save yourself, because I no longer have a way to save myself.” I ran out of the house and lay down in a sugarcane field. When [my father] left the house behind me, he ran into [the Nyatura]. They tied his hands and then locked him in the house and burned it. I heard my father screaming before he died.

During an attack near Buloto village, in Masisi territory, on November 3, 2012, Nyatura fighters killed four women and two children. A 20-year-old woman who witnessed the attack said that a group of Nyatura armed with guns, machetes, spears, and knives, and dressed in civilian trousers and military tops, surprised her, her older sister, and a friend when they were going to their farms. They tried to flee, but the Nyatura shot the woman’s sister and her friend. “When they fell on the ground, they [the Nyatura] came to them and they started cutting them with machetes so they would die,” she said. Overcome with fear, the woman who survived said she passed out and only came to when she heard young people coming to collect the bodies.

A 25-year-old woman and mother of four said that Nyatura attacked her village in Masisi territory on July 25, 2012:

The first thing [they did], was to shoot dead my husband. Then they asked me to choose between death and being raped. I chose to be raped because of my children. They all raped me, one after another. When they finished, they looted my house, they took everything. Then they burned the house and my husband was burned inside. We could not bury him.

Forced Recruitment of Children

Nyatura commanders have forcibly recruited scores of children into their ranks. During screenings of Nyatura members who surrendered in 2012 and 2013, UN child protection officials identified and separated 227 children who were former members of Nyatura armed groups.

A 2013 report by the United Nations Stabilization Mission in Congo (MONUSCO) on child recruitment documented the new recruitment of 185 boys and 5 girls by the Nyatura between January 2012 and August 2013. The UN cited Habarugira as one of the main child recruiters. Thirty-four of the children were under 15, the youngest of them 11, and 33 more were 15. International law prohibits armed groups from recruiting and using children under 18, and deploying children under 15 is a war crime.

The Nyatura recruited children on the road to the market, in the market, on their way home from school, or while the children were farming or walking to their fields. The fighters forced children to participate in military training, and those accused of insubordination were badly beaten or held in underground prisons without food. While some of the children were used for domestic work, many were sent to the battlefield, including younger children. Six child fighters were killed as a result of clashes, witnesses reported, including two boys ages 12 and 13. Re-recruitment was also prevalent. Many children said Nyatura commanders forced them to rejoin the movement after they had been demobilized and reunited with their families.

Habarugira told Human Rights Watch in November 2013 that he had no children in his ranks but admitted that he received four child soldiers from a Nyatura commander, Kapopi, based near Luke in Masisi territory.