Many have been arbitrarily detained, imprisoned, or forcibly disappeared. Some died while in state custody. Some live with permanent physical ailments and mental trauma as a result of torture by the authorities. Some, after suffering years of unrelenting harassment, fled China.

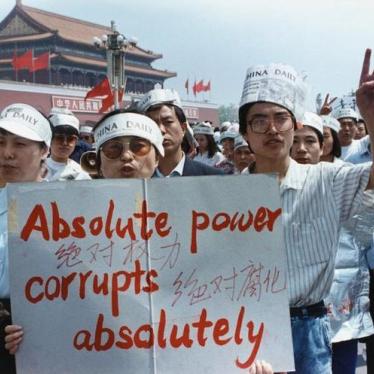

Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leaders saw the protests at Beijing’s Tiananmen Square and across major cities in the spring of 1989 as an existential threat to their rule. One lesson the CCP took away from the event was to nip any independent activism and peaceful criticism in the bud.

For the past 30 years, Human Rights Watch has continually documented the Chinese government’s repression of activists. We covered in detail the arrests and trials of Tiananmen participants; released a report jointly with the nongovernmental organization Human Rights in China that revealed the names of 522 Tiananmen prisoners that few had known existed; and published multiple interviews with protest participants. Human Rights Watch also consistently called for the Chinese government to address the human rights violations related to the crackdown and hold those officials legally accountable for the killings.

Human Rights Watch marks this somber 30th anniversary of the Tiananmen Massacre by honoring those across the years who have struggled to stand up to power and advance the rule of law, freedom of expression, and religious freedom in China.

Pre-Beijing Olympics: Lengthy Sentences for Organizing Political Parties, Rise of the Rights Defense Movement

Initially, in the wake of global condemnation following Tiananmen, Beijing made some efforts to present a less brutal posture to the world. In the 1990s and early 2000s, as Beijing sought to court foreign investment, gain entry to the World Trade Organization, and win the bid to host the 2008 Summer Olympics, it gradually loosened control of some aspects of society. Government decisions such as releasing prominent political dissidents Wei Jingsheng and Wang Dan to exile in 1997 and 1998 respectively, removing the provision on “counterrevolution” from the Criminal Law in 1997, and signing – though never ratifying – the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights in 1998 filled civil society activists with optimism.

Yet the CCP’s zero tolerance toward organized political opposition remained unmistakably clear. When some veterans of the 1989 demonstrations attempted to form political parties, their efforts were met with lengthy prison sentences. In 1993, activist Liu Wensheng was handed a 10-year sentence for organizing the China Social Democratic Party. In 1994, democracy activist Hu Shigen was sentenced to 20 years for trying to establish the China Freedom and Democracy Party.

Some of the activists who tried to form the China Democracy Party received long prison terms. In 1998, Xu Wenli and Qin Yongmin were sentenced to 13 and 12 years respectively, and in 1999, Liu Xianbin was given a 13-year prison term. In June 2002, Chinese authorities abducted party organizer Wang Bingzhang in Vietnam and brought him back to China, where he received life in prison on espionage and terrorism charges.

While political repression persisted, the Chinese economy grew rapidly, society became more open, and people gained more education and international experiences. As a result, people across China became increasingly prepared to challenge authorities over volatile livelihood issues, such as land seizures, forced evictions, environmental degradation, and employment discrimination.

In March 2003, a young migrant worker named Sun Zhigang was beaten to death after being taken to a “custody and repatriation center” by the police for not carrying his residence permit. Sun’s death sent shock waves through the country. Three legal scholars – Xu Zhiyong, Teng Biao, and Yu Jiang – submitted a recommendation to the legislature, arguing that the custody and repatriation system violated the constitution and should be abolished. That June, the government unexpectedly did so. The legal victory brought intellectuals and activists hope for rule of law in China.

Against such a backdrop, a loose national network of lawyers, activists, and journalists formed the “weiquan” (or “rights defense”) movement. Working within the legal and political constraints, they pushed censorship boundaries, monitored and documented human rights cases, defended victims of abuses in court, exposed official wrongdoing, and called for political reforms.

But the environment for human rights activism started to deteriorate in the run-up to the 2008 Beijing Summer Olympics, as authorities expanded the domestic security apparatus and muzzled several prominent activists: in August 2006, Chen Guangcheng, a blind, self-educated lawyer who documented abuses of China’s family planning law, was sentenced to four years and three months in prison.

That December, human rights lawyer Gao Zhisheng, who had defended Falun Gong practitioners and underground Christians, was sentenced to three years in prison for “inciting subversion of state power.”

In April 2008, leading HIV/AIDS advocate Hu Jia was sentenced to three-and-a-half years in prison for “inciting subversion of state power.” Despite the harsh punishments, the three activists – and many others – all continued their activism upon release.

In the spring of 2008, prominent writer Liu Xiaobo and others drafted Charter 08, an online petition urging China’s leadership to put human rights, democracy, and the rule of law at the core of the Chinese political system. The charter, an earnest effort by activists and intellectuals to rally the society around the common cause of human rights, was signed by more than 300 people from a cross-section of society, and by several prominent figures including retired party officials and former newspaper editors.

In May 2008, a devastating earthquake shook the southwest province of Sichuan. An estimated 70,000 people died, many of them schoolchildren whose shoddily built schools collapsed. Authorities mercilessly repressed parents and activists’ demand for information about quake-related deaths and damages. Police harassed and beat renowned artist Ai Weiwei after he initiated an independent survey of the student deaths. In 2009, a court in Chengdu sentenced human rights activist Huang Qi to three years in prison in response to his investigation of poor school construction. In 2010, literary editor and environmental activist Tan Zuoren was sentenced to five years on charges of “subversion” related to his compilation of a list of children killed during the earthquake.

In February 2011, an online appeal calling for people in China to emulate the Arab Spring uprisings resulted in small gatherings of curious onlookers in Beijing and several other cities. The authorities reacted by rounding up over a hundred of the country’s most outspoken critics, including artist Ai Weiwei, human rights lawyers Teng Biao and Jiang Tianyong, and forcibly disappearing them for weeks outside of any legal procedure. Upon their release, some of those individuals reported being subjected to forced sleep deprivation, abusive interrogations, and threats while in custody. Beijing’s disproportionate response to a nonexistent “revolution” indicated a fundamental fear of independent activism.

Xi Era: Clampdowns on Rights Defense Movement, Independent News Websites, Minority Rights

In November 2012, Xi Jinping ascended to power as general secretary of the CCP. His tenure as China’s top leader has been marked by ever-increasing control of all aspects of society and harsh crackdowns on human rights activism.

In July 2013, authorities arrested Xu Zhiyong, a prominent rights activist and co-founder of the New Citizen Movement, an initiative to develop civil society in China within the confines of the one-party political system. Xu was later sentenced to four years in prison.

In March 2014, longtime activist Cao Shunli died in a hospital in Beijing, a month after being transferred from a detention center when she fell into a coma. Cao was arbitrarily detained by police at the Beijing Airport in September 2013, while trying to leave to participate in a training session on human rights at the United Nations in Geneva.

In April 2014, the Beijing police detained veteran journalist Gao Yu for “illegally obtaining” “Document No. 9,” an internal Communist Party document warning its members against “seven perils” including “universal values,” civil society, and a free press. Gao was later sentenced to seven years in prison for leaking state secrets. The harsh crackdowns on free speech following the issuance of the document in April 2013 suggested its significance in the CCP’s ideological trajectory.

In July 2015, Tenzin Delek Rinopche, a Tibetan Buddhist monk, known throughout the Tibetan community for his work building schools, a monastery, and an orphanage, died in a Sichuan prison after reportedly being tortured. He had been given a suspended death sentence in 2002, commuted in 2005 to life in prison, for his alleged role in a bombing earlier that year. He was denied a lawyer of his choice, not allowed access to the evidence against him, and tried in secret.

In March 2015, authorities detained five feminists for 37 days on charge of “picking quarrels” after they planned to post signs and distribute leaflets to raise awareness about sexual harassment, sparking a widespread international outcry. In the ensuing years, women’s rights activists continued to face police harassment, intimidation, and forced eviction.

Authorities dealt the rights defense movement a severe blow in July 2015 by rounding up and interrogating without counsel about 300 rights lawyers, legal assistants, and activists across the country. While most were soon released, some received heavy sentences. In 2016, a court in Tianjin sentenced human rights lawyer Zhou Shifeng and democracy activist Hu Shigen to seven years and seven-and-a-half years in prison respectively after convicting them of “subversion.” In 2017, a Tianjin court convicted activist Wu Gan of “subversion” and sentenced him to eight years in prison. In 2019, lawyer Wang Quanzhang was sentenced to four-and-a-half years for “subversion.”

Since 2016, the Chinese government has tried to eliminate the country’s few independent human rights news platforms by jailing their founders and key members. In June 2016, authorities detained citizen journalist and protest chronicler Lu Yuyu and later sentenced him to four years in prison on charges of “picking quarrels.” In December 2018, Zhen Jianghua, executive director of the website Human Rights Campaign in China, was convicted of “inciting subversion” and sentenced to two years in prison. In January 2019, after over two years in detention, Liu Feiyue, founder of the website Civil Rights and Livelihood Watch, was sentenced to five years for “inciting subversion.” Police detained Huang Qi, founder of the human rights website “64 Tianwang,” in November 2016. The status of Huang’s prosecution is currently unclear as authorities have kept the trial secret.

On July 13, 2017, the Chinese human rights community was stricken by a profound loss: At the age of 61 and after serving nearly 9 years of his 11-year prison sentence for “inciting subversion,” Nobel Peace laurate Liu Xiaobo died from complications of liver cancer while being guarded by state security. To many who have worked to improve human rights in China, Liu’s death marked dark times for dissent.

In May 2018, Chinese authorities sentenced Tibetan language rights activist Tashi Wangchuk to five years for “inciting separatism.” Tashi Wangchuk was detained in January 2016 after appearing in a New York Times video in which he advocated for the rights of Tibetans to learn and study in their mother tongue.

Starting in mid-2018, authorities launched a national crackdown on labor activism, detaining dozens of workers and student activists in several cities, including Yue Xin, a graduate of Peking University who had been known for her activism in China’s #MeToo movement, and Wei Zhili, an editor of the workers’ rights news website iLabour.

In December 2018, police detained the pastor and scores of members of Early Rain Covenant Church, an independent Protestant church in the southwestern city of Chengdu. Pastor Wang Yi, a prominent member of China’s Christian community and a former legal scholar, and his wife, Jiang Rong, are currently in police custody, accused of “inciting subversion.”

The Fight Goes On

Human rights activists are now enduring their worst persecution since peaceful protesters took to Tiananmen Square and streets across China in 1989. Yet, despite the suffocating political environment, the fight for a democratic, rights-respecting China continues. The spirit of freedom lives on, passing from one generation to the next.

While 64-year-old Qin Yongmin is serving his 13-year sentence in a Wuhan jail for “subverting state power,” 22-year-old Yue Xin is being detained in an undisclosed location for defending worker’s rights. In October 2016, after more than 27 years behind bars, Miao Deshun, a former factory worker and the last prisoner held for the Tiananmen Square protests, was released. According to fellow prisoners, Miao had refused to admit to any wrongdoing, and as a result, was tortured and periodically put in solitary confinement.

As prominent activist Hu Jia said, “I won’t change, because this is based on feeling. I don’t believe the Chinese Communist Party is made of iron. I have never lost faith. I don’t think the power of evil can last forever. It won’t.” Every year ahead of the Tiananmen Anniversary, Hu is sent on an enforced “vacation” outside of Beijing, during which he is closely monitored. It is one of the ways authorities silence dissent during holidays and political events – and yet, the dissenters will not be silenced.

Human Rights Watch will continue to speak out against abuses pertaining to the Tiananmen Massacre until those responsible for the killings and persecutions are held to account.