(New York) – Residents of Venezuela’s southern Bolívar state are suffering amputations and other horrific abuses at the hands of armed groups, including Venezuelan groups called “syndicates” in the area and Colombian armed groups operating in the region, both of which exercise control over gold mines, Human Rights Watch said today. The armed groups seem to operate largely with government acquiescence, and in some cases government involvement, to maintain tight social control over local populations.

Venezuela has reserves of highly valued resources like gold, diamonds, and nickel, as well as coltan and uranium. Although the government has announced efforts to attract partners for legal mining and a crackdown on illegal mining, most gold mining in southern states, including Bolívar, is illegal, with much of the gold smuggled out of the country. The various syndicates that control the mines exert strict control over the populations who live and work there, impose abusive working conditions, and viciously treat those accused of theft and other offenses – in the worst cases, they have dismembered and killed alleged offenders in front of other workers.

“Poor Venezuelans driven to work in gold mining by the ongoing economic crisis and humanitarian emergency have become victims of macabre crimes by armed groups that control illegal mines in southern Venezuela,” said José Miguel Vivanco, Americas director at Human Rights Watch. “It is critical for gold buyers and refineries to ensure that any Venezuelan gold in their supply chains is not stained with the blood of Venezuelan victims.”

The operations of these illegal mines are also having a devastating impact on the environment and the health of workers, local sources said. Internal economic migration due to the economic and humanitarian crisis in Venezuela has increased the number of people seeking to work in mining areas. Many residents live in fear and are exposed to harsh working conditions, poor sanitation, and an extremely high risk of diseases such as malaria.

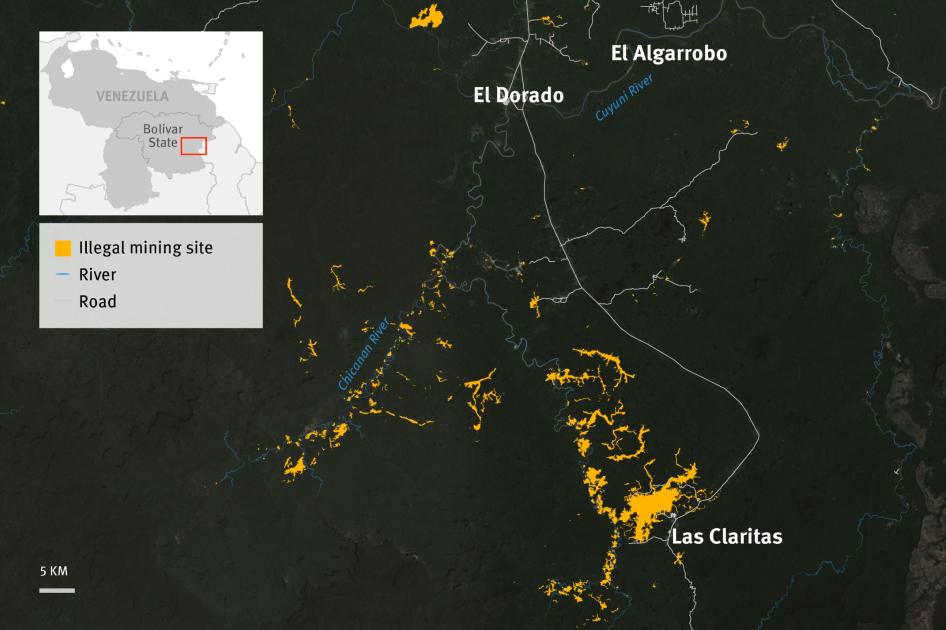

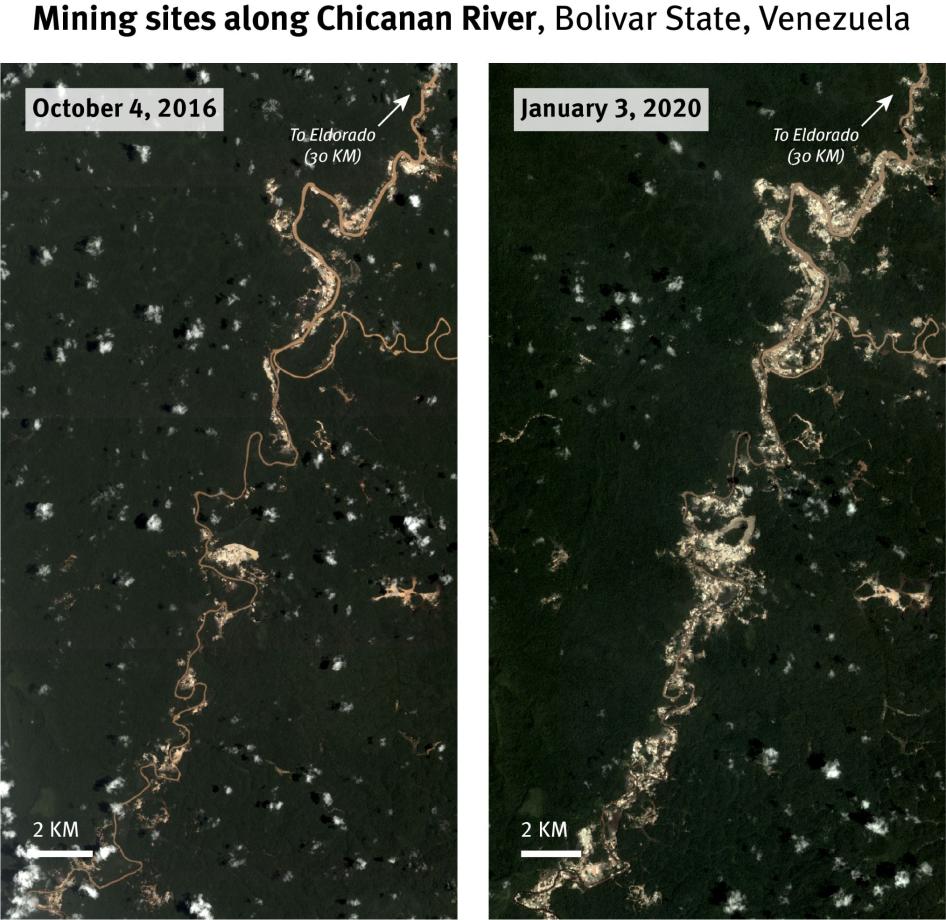

In October 2019, Human Rights Watch interviewed 21 people who had worked in mines or mining towns in Bolívar state in 2018 and 2019, including the mines near Las Claritas, El Callao, El Dorado, and El Algarrobo. In October and November, Human Rights Watch interviewed 15 other people, including leaders of indigenous groups in the area, journalists and experts who visited the area recently, and family members of people working in mines, and reviewed reports by independent groups and media outlets, which were consistent with accounts from the people interviewed in the field. Human Rights Watch also reviewed satellite imagery that shows the growth of mining in this area.

Numerous people interviewed said that many mines in Bolívar are under the tight control of Venezuelan syndicates or Colombian armed groups. The International Crisis Group has reported that both the Colombian rebel group National Liberation Army (Ejército de Liberación Nacional, ELN) and at least one dissident group that emerged from the demobilized Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia, FARC) operate in the area. Several people interviewed also said that these groups were active in Bolívar.

People interviewed also said that Venezuelan authorities are aware of the illegal mining activities. Ten people who worked at the mines, two journalists covering the area, and a local indigenous leader said that state security agents have visited mining sites to collect bribes. Some of these sources said they witnessed this. Two people working in the mines and the indigenous leader, interviewed by Human Rights Watch separately, claimed they saw a top official from the Nicolás Maduro government visit the mines in different incidents.

The armed groups, who are effectively in charge of the mines and the settlements that have grown up around them, brutally enforce their rule. “Everyone knows the rules,” one resident said. “If you steal or mix gold with another product, the pran [the syndicate leader] will beat or kill you.” Another said “They are the government there…. If you steal, they ‘disappear’ you.”

As detailed below, four residents said that they witnessed members of syndicates amputating or shooting the hands of people accused of stealing. Several other residents said they knew of cases in which syndicate members had cut offenders into pieces with a chainsaw, ax, or machete.

Residents are also exposed to mercury, which miners use to extract the gold, despite it being prohibited in Venezuela. Mercury can cause serious health problems, even in small amounts, with toxic effects on the nervous, digestive, and immune systems, and on lungs, kidneys, skin, and eyes. Studies conducted in mining areas in Bolívar many years ago already found high levels of mercury exposure, including among women and children, for whom the health risks are even higher and, for pregnant women, include serious disability or death of the fetus and, if carried to term, the child.

In addition, residents described consistently harsh working conditions in the mines, including working 12-hour shifts without any protective gear and children as young as 10 working alongside adults.

The malaria epidemic affecting Venezuela is closely correlated with the upsurge of illegal mining in the south of Venezuela. Often, miners live outdoors in tents, which increases their exposure to mosquitoes. Deforested mining pits, which fill with rainwater, provide an excellent breeding environment for malaria-carrying mosquitoes.

Nearly every person interviewed who had worked in mines or mining towns had had malaria, many of them multiple times. The public health system, amid the humanitarian emergency in the country, has not been able to provide treatment to everyone. Several interviewees said they sometimes had to purchase antimalarial drugs, which could cost up to two grams of gold, currently about US$100 on the international market.

Human Rights Watch has been unable to find any public information regarding investigations into the criminal responsibility of government officials or Venezuelan security forces implicated in these abuses.

On November 14, Human Rights Watch requested information from Venezuela’s authorities on the status of prosecutions against those responsible for abuses committed by armed groups in Bolívar, including government officials and members of Venezuelan security forces complicit in abuses, but has received no response.

Human Rights Watch was unable to identify whether any of the gold mined under the control of syndicates was sold or whether it is in the supply chain of any specific companies. Nonetheless, companies should be vigilant about gold from Venezuela and undertake human rights due diligence to identify, prevent, mitigate, and account for their impact on human rights connected to their operations, consistent with the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights.

In the case of Venezuelan gold, this includes identifying and assessing risks in supply chains, monitoring a business’ human rights impact on an ongoing basis, publishing information about due diligence efforts, and having processes in place to remediate adverse human rights impacts of their actions.

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) has stated that businesses have an obligation to adopt due diligence procedures to ensure that the minerals they engage with do not come out of “conflict” or “high-risk” areas – that is, areas in which armed conflict, widespread violence, collapse of civil infrastructure, or other risks of harm to people are present.

“National and international companies buying gold from Venezuela should know whether it comes from mines in Bolívar state and should have due diligence procedures in place to ensure that their supply chains are free from illicit, exploitative, and violent activities,” Vivanco said. “If companies find that their gold supply is linked to some of these abuses, or are unable to trace its source, they should work to fix those problems or cease working with those suppliers.”

For further information on Human Rights Watch’s findings, see below.

Illegal Gold Mining in Venezuela

According to international and local groups, the vast majority of gold mined in Venezuela is reported to be illegal, an assessment consistent with testimony gathered by Human Rights Watch.

Some of the gold produced is sold to Venezuela’s Central Bank, but much of it is smuggled through Venezuela’s borders, reportedly reaching countries including Turkey, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), and Switzerland. The total amount is difficult to determine precisely due to it being illegal.

Former President Hugo Chávez announced the Orinoco Mining Arc in 2011 with the original purpose of nationalizing the exploitation and export of metals and non-metals. This area includes the Canaima National Park, a UNESCO Heritage Site, and indigenous territories.

On February 24, 2016, President Nicolás Maduro created the “National Strategic Zone of Development of Orinoco Mining Arc” to further develop this area of 111,843 square kilometers – 12 percent of the country – in several states, including Bolívar, for mining, with the stated purpose of extracting thousands of tons of gold, diamonds, and other minerals.

Maduro signed the 2016 decree without consultation or approval by the National Assembly, as the constitution requires. According to the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights and members of local indigenous communities interviewed by Human Rights Watch, the government did not carry out appropriate environmental impact assessments or consultations with indigenous peoples living there beforehand, as the constitution also requires.

In 2016, Maduro said the government had signed mining deals with foreign companies worth $5.5 billion. In November 2018, Maduro introduced a “Gold Plan” to promote investment in gold starting in 2019, projecting profits to total $5 billion in 2019. But, as of February 2019, no major deal with foreign firms had materialized and most mines have remained under the control of non-state armed groups, according to the International Crisis Group.

The state company Minerven reportedly receives its gold from non-state affiliated mine operations and the military transports it to the Central Bank in Caracas, which in turn sells the gold to businesses in countries such as Turkey and the UAE, according to local and international sources. In December 2018, Maduro also announced that he had signed contracts to export billions of dollars’ worth of gold to partners such as Russia.

However, miners who have worked for Minerven alleged that only a small portion of Venezuela’s gold production ends up at the Central Bank. Buyers instead allegedly make more money smuggling most of the gold out of the country.

In October 2019, Maduro announced that he would assign the management of one gold mine to each state governor who belongs to the official state party. In regions controlled by opposition governments, the mining revenue would be channeled through a “social protection corporation” designated by his government.

Accountability for Crimes Committed in Gold Mines

The head of each syndicate, called pran in Venezuela, exercises control over the syndicate’s territory, residents said. Different syndicates control different specific mining areas, where each sets the rules and brutally enforces them. Miners are required to pay a large portion of the gold they obtain – up to 80 percent – to the syndicate, while residents working in shops or restaurants in mining towns must pay a set amount of gold per week to operate, according to residents.

While Venezuelan authorities have announced operations aimed at detaining people, including some public officials, involved in illegal mining, they have not made information public about any actions to investigate and punish the crimes that constitute human rights violations and were committed in the mines with the acquiescence or participation of security forces, such as those described in this publication.

Maduro has stated his intention to fight against illegal mining operations in the Arco Minero, and in June 2018, Venezuelan authorities announced an operation called Manos de metal (“Metal Hands”) to crack down on illegal gold trafficking. The authorities claim they have issued arrest warrants for 39 people allegedly involved in selling gold abroad, including Minerven’s vice president. According to the Attorney General’s Office, 32 arrest warrants that were issued have yet to be executed, 9 people have been arrested, 12 charges filed, 426 bank accounts blocked, and 45 vehicles retained relating to gold smuggling as of August 2019.

In November 2018, Attorney General Tarek William Saab announced the arrest of Eduardo Enrique González Mejías, known as “El Tati,” who allegedly financed syndicates operating in Bolívar mines. At the same time, Saab requested an arrest warrant against the former head of the National Office of Mining Inspection, a branch of the Ministry of Popular Power for Ecological Mining Development, for granting irregular gold mining permits to Mejías. Saab also said it “is estimated that this criminal organization smuggled 150 kilograms of gold, equivalent to about $6 million that the state stopped receiving” in 2018. In August 2019, Saab also announced the arrest and an extradition order against a businessman linked to an illegal gold trafficking network from Venezuela to various countries in the Caribbean.

In November 2018, US President Donald Trump issued Executive Order 13850, which allows the U.S. to impose sanctions on those operating “in the gold sector of the Venezuelan economy.” In March 2019, the United States Department of the Treasury imposed sanctions on Minerven and its president due to the abuses and illegal control of the mines.

Violence and Abuses in the Gold Mines

In 2018, the state of Bolívar had the third highest rate of “violent deaths” in the country (107 per 100,000 inhabitants) and El Callao, Venezuela’s mining capital of 20,000 inhabitants, was the most violent municipality in Venezuela, with 620 homicides per 100,000 inhabitants, according to the Venezuelan Observatory of Violence, a nongovernmental group.

Human Rights Watch interviewed five residents who said they had witnessed shootouts between Venezuelan security forces and syndicates, or between syndicates and members of Colombian armed groups, in what appear to be efforts to gain control of the mines and the revenue from them. In several cases, dozens of people, including women and children, died or were injured in these shootouts, the residents said.

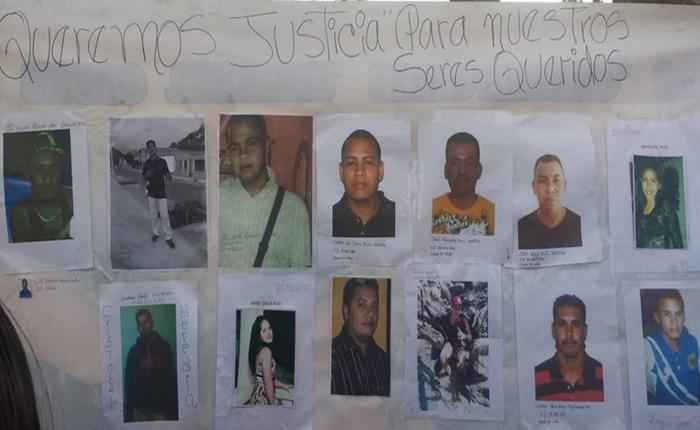

From 2012 to 2019, at least 50 people have been reported missing in Bolívar state alone, according to local sources. The real number is most likely higher, but there are no publicly available official statistics.

The following are accounts by people interviewed who described abuses.

Ligia Castro (pseudonym), 35, worked in mines in El Algarrobo and La Cucharilla in 2018, splitting work between a restaurant during the day and in the mine at night.

Castro said that, in 2018, a young woman in one of the mines was accused of stealing a pair of pants from another woman and pleaded that she had not stolen anything. Castro said that syndicate members cut off the woman’s hands with a machete, shouting “Say you won’t do it anymore!” When the woman repeated that she had not stolen the pants, they shot bullets into the air while shouting, “Here, one can’t steal.” Castro said the syndicate members put bandages on the woman, and took her away on a boat, instructing her to say she had an accident, because they knew where her family was.

Ricardo Gómez (pseudonym), 49, worked in a mine just outside Las Claritas from January to October 2017.

In April 2017, while miners were having lunch, a phone was stolen. A syndicate watchman identified a miner as the thief. Syndicate members placed a rag in his mouth and cut off his hand with an ax in front of everyone, Gómez said. Afterward, the syndicate member took the man into a car, and he has not been seen since. A week later, the miner’s family went to the mine looking for him. They asked Gómez, but he said nothing out of fear. After they left, syndicate members asked him what he had said to the family and threatened him, saying “If you say something that hurts us, you’ll also be disappeared.”

About a month later, a miner took 10 grams of gold from another miner she had sex with, Gómez said. Syndicate members seized the woman, tied her to a tree, and cut off her head with a chainsaw and chopped up the rest of her body in front of other residents, he said. “It’s all engraved in my mind,” Gómez said. “I left the mine in fear.”

Other Accounts

Another resident said that, before punishing those who break their rules, members of the syndicate force them to walk in front of other residents with a sign on them that reads “I will die because I [stole].” This resident and two others said syndicate members also cut the hair of women accused of stealing. One of them said he saw members of the syndicate take a man accused of raping a woman to the other side of the river. He said he heard the noise of a chainsaw and screams, and never saw the man again.

A 17-year-old boy said he witnessed how members of the syndicate individually amputated each finger off the hands of a miner accused of stealing gold, before amputating the remains of both hands. He said they did it in front of other mine workers so “everyone could see.” Another man said that a member of a syndicate made another 17-year-old boy, accused of stealing gold, put one hand against the other, as if he were praying, and shot seven times directly at his hands before telling him, “Go before we kill you.”

Human Rights Watch also interviewed a 16-year-old who suffered a spinal fracture when a log hit him as he was using a high-pressure hose without any kind of protective gear. A pastor who worked in a mine said some members of the syndicate there had raped girls, and their parents fear retaliation if they report the abuse.

Corroborating Reporting

A congressman from Bolívar state, independent groups, and media outlets have reported on cases of abuse consistent with those documented by Human Rights Watch. For example:

- On March 4, 2016, 28 miners working at a gold mine in Tumeremo, in Bolívar state, were reported missing, said a Bolívar congressman, Américo de Grazia. Ten days later, 17 bodies were found in a mass grave in Nuevo Callao, according to Tarek William Saab, then-Venezuelan ombudsman. Then-Attorney General Luisa Ortega Diaz also said the bodies had been found, and later confirmed that 21 miners had disappeared. Reports from witnesses obtained by de Grazia said that the 28 miners were shot in the back of their heads and dismembered with a chainsaw so an armed group could allegedly take control of the mine. On November 28, Interior Minister Gustavo González López determined the cause of the killings was due to a “gang war” over the collection of bribes. He also mentioned that the “paramilitary phenomenon” was exported from Colombia and that these groups intended to exercise political and economic control of the mining area.

- Leocer José Lugo Maíz, a 19-year-old soldier, was found mutilated – with his hands amputated, his tongue cut, and his eyes taken out – on January 14, 2019, according to media accounts. Lugo Maíz, a soldier of the National Bolivarian Guard who had deserted, was captured by a syndicate in the Yin Yan mine in El Callao. According to local media reports, Lugo was thought to be a Bolivarian National Guard informant. Syndicate members reportedly kidnapped Lugo Maíz on January 8.

- The nongovernmental group Commission for Human Rights and Citizenship (Comisión de los Derechos Humanos y Ciudadanía, CODHECIU) has collected 51 complaints of missing people in the mining municipalities in Guayana region, Bolívar, from 2012 to 2019, CODHECIU told Human Rights Watch. Of those, 10 people were found alive after being kidnapped or surviving a massacre; the whereabouts of the rest remained unknown as of September 2019. More than 60 percent of the reported cases happened between 2018 and 2019. Six families told CODHECIU that a family member had gone to work in gold mines in the area and never returned. According to CODHECIU, most of the families said they filed complaints with the investigative police CICPC but were “encouraged” by the police to stop the search. In one case, family members told CODHECIU there was no effective search for the missing person reported by the CICPC within the first hours.

Human Rights Watch spoke to the wife of one of the people featured in a local media article that covered this issue. She last heard from her husband in March 2018, after he left to go to work at a mine in Delta Amacuro state, and he has not returned since. She said she received threats and intimidation after she reported her husband missing to Venezuelan authorities and told Human Rights Watch that she received similar encouragement from CICPC to stop her search.

- On October 15, 2019, at least 16 people went missing and 6 were injured at Los Candados mine in Bolívar state during an alleged confrontation between a syndicate and the ELN, according to news reports.

- On November 22, 2019, at least eight people were reported dead in a shootout in the Pemón Ikabarú Indigenous territory, one of the mining areas in the Orinoco Mining Arc, in Gran Sabana municipality, Bolívar. Witnesses reported shots from an armed group around 7:30 p.m. in front of a local business. At least one of those confirmed dead was a member of the Bolivarian National Guard, and another was an indigenous person from the Manak Kru community. Indigenous authorities in Pemón released an official statement on the “Ikabarú massacre,” condemning the event and the presence of armed groups in indigenous territory and demanding that the massacre be investigated by the national government in conjunction with indigenous authorities.

Malaria

In the 8 years from 2010 to 2018, malaria cases in Venezuela increased by 797 percent, rising swiftly from 136,402 in 2015 to 240,613 in 2016 and 404,924 confirmed cases in 2018.

According to a report by the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) and World Health Organization (WHO), 323,392 malaria cases were reported in Venezuela between January and October 13, 2019. The Venezuelan Society of Public Health, however, estimates that there were over 1 million malaria cases in 2018, more than a 50 percent increase compared to 2017. PAHO and the WHO reported that the largest number of cases reported in 2019 were in the states of Amazonas, Bolívar, and Sucre.

As people migrate to and from Amazonas, Bolívar, and Sucre states, malaria spreads to parts of Venezuela where it has not been reported in decades, as well as to neighboring countries. The potential emergence of drug-resistant strains due to the lack of availability of effective treatment is also an emerging threat, accompanied by an increase in malaria-related mortality.

The situation is aggravated by weakened vector control programs as well. Some people interviewed by Human Rights Watch said they sometimes got treatment in public health clinics. But others said they paid up to 2 grams of gold – worth approximately $100 – for treatment, including 1 person who had to pay a nurse for it at a public health clinic. Some who could not afford to pay said they had resorted to treating malaria “with herbs.”