On May 17, 1990, the World Health Organization removed homosexuality from its list of mental disorders, recognizing homosexuality as a natural variant of human sexuality. This milestone now marks an annual celebration of sexual and gender diversities, known as the International Day Against Homophobia, Biphobia and Transphobia (IDAHOBIT). Yet the lasting impact of stigma, and “othering” is evident in the discrimination and abuse that lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people around the world continue to experience.

“Breaking the Silence” is this year’s theme, under the pall of a pandemic that has had a devastating effect on lives and livelihoods across the globe. COVID-19 has affected people across divisions of race, class, and gender and exposed the fault lines of inequality, disproportionately affecting those on the social and economic margins. In a crisis, it’s easy to lose track of progress and setbacks over the last year that have contributed to the climate in which many LGBTQ+ people experience the pandemic. The annual celebration is an opportune moment to reflect on the advances made in LGBTQ+ rights, and the challenges that remain.

In Uganda, 19 homeless gay, bisexual and transgender people have spent two months in prison on spurious charges of violating COVID-19 related curfew regulations. Forced out of their family homes, they had nowhere else to go, but police decided that for them, living in a shelter was a crime. In Hungary, Viktor Orbán has used the pandemic to rule by decree, and has introduced legislation that would ban legal gender recognition for transgender people.

In Panama, where women and men have been required to remain quarantined on alternate days, some transgender people have faced abuse from security officials, no matter which day they ventured out. In the Philippines, LGBTQ+ people experienced humiliating punishments by village officials enforcing a curfew. And religious leaders have fueled rumors that Covid-19 is divine retribution for immoral behavior – that leads to LGBTQ+ people being scapegoated, for example in Ukraine and Senegal.

At a time when access to health care is a global concern, LGBT people remain vulnerable to discrimination, driven by health workers’ personal prejudice or government policy. Tanzania is a stark example. For four years the government has targeted drop-in centers that provide care to LGBTQ+ people, banned the import of water-based lubricant, and arrested lawyers and activists who challenged these measures. HIV prevention and treatment programs had been one of the few relatively safe spaces for LGBTQ+ groups to operate.

Access to appropriate health care is a struggle for transgender people in many parts of the world. Coercive medical requirements can foster abuse. In Japan, for example, transgender people are forced to be sterilized to qualify for legal documents reflecting their gender identity. And in the U.S., the Department of Health and Human Services has proposed a rule to allow organizations with discriminatory policies to receive federal funds, and is poised to roll back Obama-era health care protections for transgender people.

LGBTQ+ people are often cast as a threat to traditional notions of the family, society and the nation. Stigma and hate speech are even more threatening in a pandemic, when vulnerable groups are blamed and targeted. In Poland, local municipalities declared towns LGBT-free zones, spurred on by a government that has waged a sustained campaign against so-called “gender ideology.” Under this rubric, women’s reproductive rights, LGBTQ+ rights, and comprehensive sexuality education are cast as a sinister, coordinated threat to “traditional values.” In the midst of the pandemic, the Polish parliament considered two bills that would be harmful to women and LGBTQ+ people.

Hostility toward LGBTQ+ people is compounded when activists are silenced. In July, the European Court of Human Rights ruled against Russia’s failure to register two NGOs working on LGBTQ+ issues, highlighting the stifling effects of Russia’s “gay propaganda” law, which effectively outlaws expression of identity.

The law’s effects were compounded most recently through spurious charges against a TV presenter for interviewing a gay man, restrictions against a lesbian activist, and by forcing a gay couple to flee with their children. An extreme manifestation of the erasure of LGBTQ+ identities are the purges against gay men and lesbians in Chechnya. Neither the purges nor the threats against activists were effectively investigated.

Attacks on free expression have been overlaid with religious objections in Poland, where an activist was charged for combining a rainbow image and a religious icon, while in Brazil a court battle ensued over a satirical film. Kenya’s Constitutional Court upheld the 2018 ban on the highly acclaimed film Rafiki in April on grounds that the ban will “protect society from moral decay.” Concert organizers in Lebanon canceled the performance of the indie band Mashrou’ Leila following pressure and threats of violence and the government’s failure to offer adequate protection. On the other hand, police in Lublin, Poland defended Pride march participants against protesters, while in Lebanon, anti-government protests afforded a unique opportunity for queer and trans visibility.

It is a truism that laws prohibiting same-sex conduct or gender expression provide tacit state sanction for discrimination and contribute to a hostile environment in which discrimination and violence occurs. The number of countries criminalizing same-sex behavior fluctuates as some decriminalize and others introduce new legislation.

Laws that were first imposed in the colonial-era have morphed into markers of post-colonial sovereignty and national identity. A week after last year’s IDAHOBIT celebrations, the Kenyan high court upheld that country’s anti-homosexuality laws based on an absurd argument that the law did not discriminate against same-sex couples. Almost a year later a high court judge in Singapore came to a similar conclusion. Gabon introduced a new penal code provision outlawing consensual same-sex activity, but Botswana’s highest court repealed that country’s archaic sodomy law as a relic of the past that rightly “belongs in museum or the archives.”

Brunei extended its penal code to include death by stoning for same-sex conduct and adultery. Following international outcry, the Sultan extended a moratorium on the death penalty. Indonesia’s controversial draft penal code revisions to outlaw all sexual relations outside of marriage drew widespread protests and were shelved. Such provisions would pose particular threats to women as well as LGBTQ+ people. Hong Kong, on the other hand, took steps to dismantle the last vestiges of its defunct sodomy law, repealed in 2007, by eliminating additional discriminatory provisions.

Taiwan became the first country in Asia to allow for same-sex marriage in adherence to a constitutional court ruling, despite a referendum that came out opposed. And Northern Ireland finally joined the rest of the United Kingdom in allowing same-sex marriage.

Violence, often with impunity, is ubiquitous for LGBTQ+ people in many parts of the world. Last May, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights referred a case of impunity in Honduras involving the 2009 assassination of Vicky Hernàndez, a transgender woman, to the Inter-American Court. In El Salvador, a judge ruled that a case against three police officers charged with aggravated homicide of Camila Díaz Córdova, a transgender woman, could proceeded to trial, though not as a hate crime.

In Uganda, LGBTQ+ rights activist Brian Wasswa, 28, was brutally murdered. Ethics Minister Simon Lokodo threatened to reintroduce a bill that would include the death penalty for “grave” consensual same-sex acts. A government spokesperson later retracted that threat.

In February, no hate motive was included in a Russian case in which 47-year-old Roman Edalov, a gay man, was killed after his attacker hurled homophobic insults. In contrast, in Belarus, police investigations into the brutal attack on a gay filmmaker and his companions led to conviction as a hate crime. And in Kazakhstan, where homophobic attitudes are pervasive, a court ruled to protect a couple’s privacy when a social media post sparked threats of violence against them. While in Morocco, an outing campaign has terrorized men who use dating apps to meet other men.

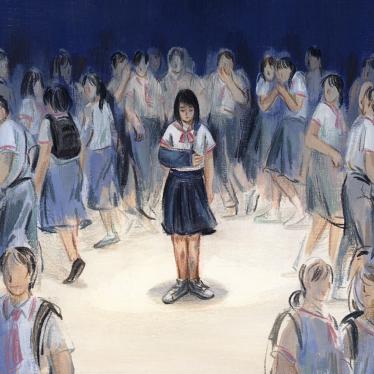

In many parts of the world, LGBTQ+ people are shunned socially and marginalized economically. There is a strong correlation between abuse, discrimination and socio-economic status. The pandemic is likely to dramatically exacerbate this situation. When LGBTQ+ kids face bullying and discrimination in school, it can affect their performance and life chances, as evident in school climate studies in Japan, the Philippines, the U.S. and Vietnam.

Transgender people in India hoped for reprieve from extreme economic vulnerability, as well as enhanced recognition and social acceptance through the long-awaited, but ultimately disappointing Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Bill, 2019. In Pakistan, a high ranking official in Karachi reassured the hijra community that they would receive government support during the pandemic. In the U.S., the Supreme Court is considering whether discrimination against LGBTQ+ workers is a form of sex discrimination prohibited by existing federal law.

As IDAHOBIT is celebrated throughout the world, as an aspect of “breaking the silence,” challenges to equal access to healthcare, education, protection from discrimination and violence, and rights to association, expression and privacy remain pressing in many parts of the world. Even in a crisis of staggering proportions, the advances that have been made in human rights, including for LGBTQ+ people, need to be protected.