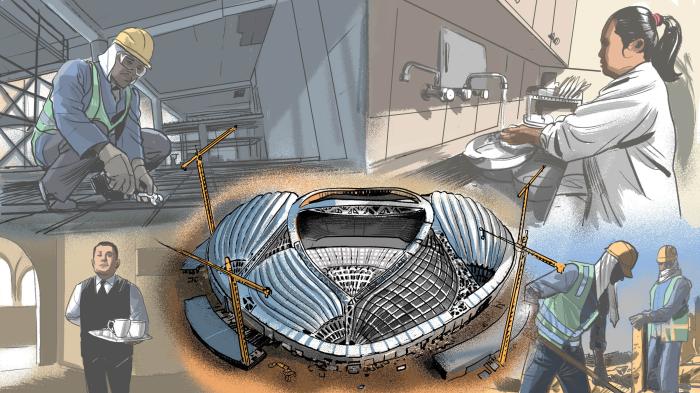

The author is one of the 93 migrant workers Human Rights Watch interviewed for a new report on salary abuses ahead of Qatar’s 2022 FIFA World Cup, he has requested anonymity for his safety; work visas and residence permits for migrant workers in Qatar are directly tied to employers, hence workers are often afraid to speak publicly against salary abuses.

Like thousands of migrant workers from Africa and Asia, I am finally in the land of my dreams, Qatar. I knew working here would be tough, but I thought I would be able to regularly send money home to my family and live decently.

I had imagined that once here, I could sneak a peek at gli Azzuri, the Italian national team and my favorite, but seeing the way Qatar treats workers like me preparing for the 2022 FIFA World Cup, my excitement dwindled.

In the land of my dreams, every day feels like a nightmare.

The soaring unemployment rate in Kenya, my home country, pushes thousands of young people to look for jobs overseas. A family friend had moved here recently to work in the hospitality industry. He appeared to have a decent life. That, plus the lack of income tax and the promise of medical coverage helped lure me here.

My friend did say that working in the Gulf is not for the faint of heart, but I asked myself if things could be worse than they are in Kenya. I have a bachelor’s degree with honors and still found no stable job opportunities in my hometown. I knew I needed something to supplement the freelance writing I was doing.

I found a local recruiting agent who agreed to facilitate my visa and job application process for a security guard job. He demanded $1,500 in recruitment fees. This is a huge amount, but I asked around and I found that all Kenyan migrant workers pay recruitment fees for a job in Qatar. My parents offered to cover me. They said it would leave them in a financial crunch, but it would be worth it to see my life take off. After working hard their whole lives, both of them will be forced to retire this year, so it is up to me to fend for myself and shoulder my family’s responsibilities.

The recruiting agent turned out to be both disorganized and surreptitious. The flight he arranged for me was an eight-hour journey from my hometown. I had paid him to secure me a job as a security guard, but after the non-refundable payments were made, when he handed me my paperwork hours before my departure, I discovered my visa and employment contract were for a cleaning position. Not to worry, he said, when I get to Qatar I can change jobs.

My Qatar dream was finally in motion as the plane powered into the gloomy night sky. I was greeted by the architectural masterpiece that is Hamad International Airport. Things were bound to pick up now, I thought. But my employer, who was supposed to meet me, was nowhere to be found. After numerous frantic phone calls, he told me to get a taxi and go to my accommodations.

Inside my room, at the shoebox accommodations I found four other workers who seemed miserable. We didn’t talk much. The place was rundown, with no beds, only used mattresses and soiled duvets which harbored an insect colony. I willed myself to be optimistic and decided to talk to my employer in the morning about changing jobs.

My employer heard my concerns and took me for an interview at a local security services company. I was offered an employment contract that seemed fair. For eight hours of work a day, my monthly salary would be 1,500 Qatari riyals ($412), I would be paid at a higher rate for any overtime work, and the employer would cover my health care and housing.

In Qatar, a migrant worker needs to get their previous employer’s written permission to change jobs while on contract. While for me, it was a smooth process, other workers have told me how difficult it was for them, and how employers often use the power they have over workers to further exploit them. My new company made it a point to inform me that they themselves never give workers the permission to change jobs. I didn’t think too much about this, I was just happy to leave my infested room and start earning money. In retrospect, I wish I had.

The legal transfer of my immigration documents took a month, without pay, and when I finally was ushered into the security company’s housing, I was ready for better days.

The new housing was better than where I had been living, but still not up to bare minimum standards. Ten of us were stacked in a stuffy room. About 15 people shared a toilet, and about 60 shared the communal kitchen, which was built for a handful of people.

Since then, with different assignments, I have lived in various places. At one point I was sleeping in the educational facility I was guarding. For the last month I have been sharing my room with five other men from my company, and for a while, water from the air conditioner was leaking onto our beds.

As for my working conditions, the four hours of overtime I put in daily are ignored in my pay slips, I work seven days a week without a day off, wages are delayed for up to three months, and during this time they don’t even provide us with a food allowance.

My March salary arrived in June, April’s salary came in July. I have not been paid for May, June, and July. For every day that my wages are delayed, I go deeper into debt, because I send 1,000 Qatari Riyals ($275) a month home and have no choice but to borrow money for food.

I have been here for more than six months, but I have not been issued a Qatar Identity Card, which is mandatory for migrant workers. Other employees tell me it takes eight to ten months for our company to issue Identity Cards. Without the card, I can’t take a complaint to the Labor Department; I can’t even step out of my housing without risking arrest.

I have not had a single off day since I started working six months ago – a single day off will cost me 50 Qatari Riyals ($14). I desperately need a few days off to fight the fatigue that is dragging me down. However, I also desperately need a complete salary to break even and start moving toward a decent life.

My assignments vary. I have worked at hotels, offices, and schools. Currently I stand for 12 hours a day, outside a hotel in one of Qatar’s upscale neighborhoods. I am tasked with directing and controlling traffic, conducting regular foot patrols, and assisting and escorting guests who enquire about whether rooms are available. My duty is made harder by the unwavering and relentless Middle East sun.

I finally got a health card after five months. Imagine being in a foreign country during a global pandemic and not having health care. To make matters worse, it seems that my company doesn’t care much about personal protective equipment. They bring gloves and masks just once in a while. The hotel staff often lends us masks. Luckily, the only person I know of who has had Covid-19 was a supervisor at the hotel before I was assigned here.

My workmates encourage me when I am at my lowest points. We understand the systematic challenges workers experience daily. The government talks about reforming labor laws but most of it feels like it is only on paper. People on the ground are really suffering and rogue employers are getting away with gross injustices. The class division is stark in Qatar. The country is one of the richest in the world, but it was built and continues to run on the fuel of its migrants. The exploitation and oppression have taken a mental and physical toll on us, but the resolve to improve our lives keeps us going.

The 2022 World Cup is another thorny matter. Even the biggest and glitziest stadiums can’t justify maltreatment of workers.

Overworked, underpaid, and left on my own without any security net, I have a false choice: stick it out, or return to Kenya, defeated and drowning in debt.

The author asked not to use his name for his protection.