EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Is the Chinese government’s greater engagement with international institutions a gain for the global human rights system? A close examination of its interactions with United Nations human rights mechanisms, pursuit of rights-free development, and threats to the freedom of expression worldwide suggests it is not. At the United Nations, Chinese authorities are trying to rewrite norms and manipulate existing procedures not only to minimize scrutiny of the Chinese government’s conduct, but also to achieve the same for all governments. Emerging norms on respecting human rights in development could have informed the Chinese government’s approach to the Belt and Road Initiative, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, and national development banks, but they have not. Chinese authorities now extend domestic censorship to communities around the work, ranging from academia to diaspora communities to global businesses.

This paper details the ways Chinese authorities seek to shape norms and practices globally, and sets out steps governments and institutions can take to reverse these trends, including forming multilateral, multi-year coalitions to serve as a counterweight to Chinese government influence. Academic institutions should not just pursue better disclosure policies about interactions with Chinese government actors, they should also urgently prioritize the academic freedom of students and scholars from and of China. Companies have human rights obligations and should reject censorship.

Equally important, strategies to reject the Chinese government’s threats to human rights should not penalize people from across China or of Chinese descent around the world, and securing human rights gains inside China should be a priority. The paper argues that many actors’ failure to take these and other steps allows Chinese authorities to further erode the existing universal human rights system — and to enjoy a growing sense of impunity.

INTRODUCTION

In recent years, the Chinese government has become considerably more active in a wide range of United Nations and other multilateral institutions, including in the global human rights system. It has ratified several core U.N. human rights treaties,[1] served as a member of the U.N. Human Rights Council (HRC), and seconded Chinese diplomats to positions within the U.N. human rights system. China has launched a number of initiatives that can affect human rights: It has created the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) under the mantra of promoting economic development, and it has become a significant global actor in social media platforms and academia.

This new activism on issues from economics to information by one of the most consequential actors in the international system, if underpinned by a serious (albeit unlikely) commitment among senior Chinese leaders to uphold human rights, could have been transformative. But the opposite has happened.[2] Particularly under President Xi Jinping’s leadership, the Chinese government does not merely seek to neutralize U.N. human rights mechanisms’ scrutiny of China, it also aspires to neutralize the ability of that system to hold any government accountable for serious human rights violations.[3] Increasingly Beijing pursues rights-free development worldwide, and tries to exploit the openness of institutions in democracies to impose its world view and silence its critics.

It is crucial — particularly for people who live in democracies and enjoy the rights to political participation, an independent judiciary, a free media, and other functioning institutions — to recall why the international human rights system exists. Quite simply, it is because often states fail to protect and violate human rights, particularly in countries that lack systems for redress and accountability. People need to appeal to institutions beyond their government’s immediate control.

Beijing is no longer content simply denying people accountability inside China: It now seeks to bolster other countries’ ability to do so even in the international bodies designed to deliver some semblance of justice internationally when it is blocked domestically.[4] Within academia and journalism, the Chinese Communist Party seeks not only to deny the ability to conduct research or report from inside China, it increasingly seeks to do so at universities and publications around the world, punishing those who study or write on sensitive topics. The rights-free development the state has sanctioned inside China is now a foreign policy tool being deployed around the world.

Beijing’s resistance to complying with global public health needs and institutions in the COVID-19 crisis,[5] and its blatant violation of international law with respect to Hong Kong,[6] should not be seen as anomalies. They are clear and concerning examples of the consequences for people worldwide not only of a Chinese government disdainful of international human rights obligations but, increasingly, also seeking to rewrite those rules in ways that may affect the exercise of human rights around much of the world. Chinese authorities fear that the exercise of these rights abroad can directly threaten the party’s hold on power, whether through criticism of the party itself or as a result of holding Beijing accountable under established human rights commitments.

CHINA AND THE U.N. HUMAN RIGHTS SYSTEM

In June, Human Rights Council member states adopted China’s proposed resolution on “mutually beneficial cooperation” by avoteof 23-16, with eight abstentions.[7] This vote capped a two-year effort that is indicative of Beijing’s goals and tactics of slowly undermining norms through established procedures and rhetoric, which have had significant consequences on accountability for human rights violations. The effort became visible in 2018 when the Chinese government proposed what is now known as its “win-win” resolution,[8] which set out to replace the idea of holding states accountable with a commitment to “dialogue,” and which omitted a role for independent civil society in HRC proceedings. When it was introduced, some member states expressed concern at its contents. Beijing made minor improvements and, along with the perception at the time that the resolution had no real consequences, it was adopted 28-1. The United States was the only government to vote against it.

China’s June resolution seeks to reposition international human rights law as a matter of state-to-state relations, ignores the responsibility of states to protect the rights of the individual, treats fundamental human rights as subject to negotiation and compromise, and foresees no meaningful role for civil society. China’s March 2018 resolution involved using the council’s Advisory Committee, which China expected would produce a study supporting the resolution. Many delegations expressed concern, but gave the resolution the benefit of the doubt, abstaining so they could wait to see what the Advisory Committee produced.

China’s intentions soon became clear: Its submission [9] to the Advisory Committee hailed its own resolution as heralding “the construction of a new type of international relations.”[10] The submission claims that human rights are used to “interfere” in other countries’ internal affairs, “poisoning the global atmosphere of human rights governance.”

This is hardly a coincidence: China has routinely opposed efforts at the council to hold states responsible for even the gravest rights violations, and the submission alarmingly speaks of “so-called universal human rights.” It is nonetheless encouraging that 16 states voted against this harmful resolution in June 2020, compared with only one vote against in 2018, signaling increasing global concern with China’s heavy-handed and aggressive approach to “cooperation.”

That the resolution nonetheless passed reflects the threat China poses to the U.N. human rights system. In 2017, Human Rights Watch documented China’s manipulation of U.N. review processes, harassment, and intimidation of not only human rights defenders from China but also U.N. human rights experts and staff, and its successful efforts to block the participation of independent civil society groups, including organizations that do not work on China.[11]

In 2018, China underwent its third Universal Periodic Review (UPR), the process for reviewing all U.N. member states’ human rights records. Despite — or perhaps because — Chinese authorities had since China’s previous review opened an extraordinary assault on human rights, Chinese diplomats did not just resort to some of its past practices. These had included providing blatantly false information at the review, flooding the speakers’ list with friendly states and government-organized civil society groups, and urging other governments to speak positively about China.

This time around China also pressured U.N. officials to remove a U.N. country team submission from the UPR materials (ironically that report was reasonably positive about the government’s track record),[12] pressured Organisation of Islamic Cooperation member states to speak positively about China’s treatment of Uyghur Muslims, and warned other governments not to attend a panel event about Xinjiang.

China has so far fended off calls by the high commissioner for human rights and several HRC member states for an independent investigation into gross human rights abuses in Xinjiang, the region in China where an estimated one million Uyghurs and other Turkic Muslims remain arbitrarily detained.[13] Typically, violations of this magnitude would have already yielded actual accountability proceedings, but China’s power is such that three years into the Xinjiang crisis there is little forward movement.

In July 2019, two dozen governments sent a letter to the Human Rights Council president — though they were unwilling to make the call orally on the floor of the HRC — urging an investigation.[14] China responded with a letter signed by 37 countries, mostly developing states with poor human rights records. In November, a similar group of governments delivered a similar statement at the Third Committee of the U.N.;[15] China responded with a letter signed by 54 countries.[16]

Beijing also seeks to ensure that discussions about human rights more broadly take place only through the human rights bodies in Geneva, and not other

U.N. bodies, particularly the Security Council. China contends that only the HRC has a mandate to examine them — a convenient way of trying to limit discussions even on the gravest atrocities. In March 2018, it opposed a briefing by then-High Commissioner for Human Rights Zeid Ra’ad al Hussein to the Security Council on Syria,[17] and in February 2020 it blocked a resolution at the Security Council on the plight of Myanmar’s ethnic Rohingya.[18]

U.N. human rights experts, typically referred to as “special rapporteurs,” are key to reviews and accountability of U.N. member states on human rights issues. One of their common tools is to visit states, but China has declined to schedule visits by numerous special rapporteurs, including those with mandates on arbitrary detention, executions, or freedom of expression.[19]

It has allowed visits by experts on issues where it thought it would fare well: the right to food in 2012, a working group on discrimination against women in 2014, and an independent expert on the effects of foreign debt in 2016.[20] In 2016, China allowed a visit by Philip Alston, then the special rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights, who ended his visit early when authorities followed him and intimidated people he had spoken to.[21 ] Since that time, China has only allowed a visit by the independent expert on the rights of older people in late 2019.

China also continues to block the Office of the U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights from having a presence in China. While there are two dozen other U.N. agencies in China, they have rarely invoked their mandate to promote human rights.

In late June, 50 U.N. current and former special procedures — the most prominent group of independent experts in the U.N. human rights system — issued a searing indictment of China’s human rights record and call for urgent action.[22] The experts denounced the Chinese government’s “collective repression” of religious and ethnic minorities in Xinjiang and Tibet, the repression of protest and impunity for excessive use of force by police in Hong Kong, censorship and retaliation against journalists, medical workers, and others who sought to speak out following the COVID-19 outbreak, and the targeting of human rights defenders across the country. The experts called for convening a special session on China, creating a dedicated expert on China, and asking U.N. agencies and governments to press China to meet its human rights obligations. It remains to be seen whether and how the U.N. secretary-general, the high commissioner for human rights, and the Human Rights Council will respond.

Despite its poor human rights record at home, and a serious threat to the U.N. human rights system, China is expected to be reelected to the Human Rights Council in October. Absent a critical mass of concerned states committed to serving as a counterweight to both problems, people across China and people who depend on this system for redress and accountability are at serious risk.

CHINA’S PUSH FOR RIGHTS- FREE DEVELOPMENT

For the last several decades, activists, development experts, and economists have made gains in creating legal and normative obligations to ensure respect and accountability for human rights in economic development. By the time China became the world’s second-largest economy in 2010, major multilateral institutions including the World Bank Group and International Monetary Fund had already adopted standards and safeguards policies on community consultation, transparency, and other key human rights issues. In 2011, the United Nations adopted the Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights. Taken together, these emerging global norms should have afforded Beijing a template to pursue development with clear respect for human rights, but neither China’s development banks nor BRI shows signs of doing so.[23]

Beijing’s trillion-dollar BRI infrastructure and investment program facilitates Chinese access to markets and natural resources across 70 countries. Aided by the frequent absence of alternative investors, the BRI has secured the Chinese government considerable good- will among developing countries, even though Beijing has been able to foist many of the costs onto the countries that it is purporting to help.

China’s methods of operation appear to have the effect of bolstering authoritarianism in “beneficiary” countries, even if both democracies and autocracies alike avail themselves of China’s BRI investments or surveillance exports.[24] BRI projects — known for their “no strings” loans — largely ignore human rights and environmental standards.[25] They allow little if any input from people who might be harmed, allowing for no popular consultation methods. There have been numerous violations associated with the Souapiti Dam in Guinea and the Lower Sesan II Dam in Cambodia, both financed and constructed mainly by Chinese state-owned banks and companies.[26]

To build the dams, thousands of villagers were forced out of their ancestral homes and farmlands, losing access to food and their livelihoods. Many resettled families are not adequately compensated and do not receive legal title to their new land. Residents have written numerous letters about their situation to local and national authorities, largely to no avail. Some projects are negotiated in backroom deals that are prone to corruption. At times they benefit and entrench ruling elites while burying the people of the country under mountains of debt.

Some BRI projects are notorious: Sri Lanka’s Hambantota port, which China repossessed for 99 years when debt repayment became impossible, or the loan to build Kenya’s Mombasa-Nairobi railroad, which the government is trying to repay by forcing cargo transporters to use it despite cheaper alternatives. Some governments — including those of Bangladesh, Malaysia, Myanmar, Pakistan, and Sierra Leone — have begun backing away from BRI projects because they do not look economically sensible.[27] In most cases, the struggling debtor is eager to stay in Beijing’s good graces. In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, China has made some pronouncements on debt relief, yet it remains unclear on how that will actually work in practice.[28]

BRI loans also provide Beijing another financial lever to ensure support for China’s anti-rights agenda in key international forums, with recipient states sometimes voting alongside Beijing in key forums. The result is at best silence, at worst applause, in the face of China’s domestic repression, as well as assistance to Beijing as it undermines international human rights institutions. Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan, for example, whose government is a major BRI recipient, said nothing about his fellow Muslims in Xinjiang as he visited Beijing, while his diplomats offered over-the- top praise for “China’s efforts in providing care to its Muslim citizens.”[29]

Similarly, Cameroon delivered fawning statements of praise for China shortly after Beijing forgave it millions in debt: Referencing Xinjiang, it lauded Beijing for “fully protect[ing] the exercise of lawful rights of ethnic minority populations” including “normal religious activities and beliefs.”[30] China’s national development banks, such as the China Development Bank and the Export-Import Bank of China, have a growing global reach but lack critical human rights safeguards. The China-founded multilateral AIIB is not much better. Its policies call for transparency and accountability in the projects it finances and include social and environmental standards, but do not require the bank to identify and address human rights risks.[31] Among the bank’s 74 members are many governments that claim to respect rights: much of the European Union including France, Germany, the Netherlands, and Sweden, along with and the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand.

CHINESE GOVERNMENT THREATS TO FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION WORLDWIDE

Beijing’s censorship inside China is well documented, and its efforts to disseminate propaganda through state media worldwide are well known. But Chinese authorities no longer appear content with these efforts and are expanding their ambitions. Under Xi Jinping’s leadership, Chinese authorities increasingly seek to limit or silence discussions about China that are perceived to be critical, and to ensure that their views and analyses are accepted by various constituencies around the world, even when that entails censoring through global platforms.

Chinese authorities have long monitored and conducted surveillance on students and academics from China and those studying China on campuses around the world. Chinese diplomats have also complained to university officials about hosting speakers — such as the Dalai Lama — whom the Chinese government considers “sensitive.” Over the past decade, as a result of decreasing state funding to higher education in Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom, and the United States, universities are increasingly financially dependent on the large number of fee-paying students from China, and on Chinese government and corporate entities. This has made universities susceptible to Chinese government influence.

The net result? In 2019, a series of rigorous reports documented censorship of and self-censorship by some administrators and academics who did not want to irk Chinese authorities.[32] Students from China have reported threats to their families in China in response to what those students had said in the classroom.

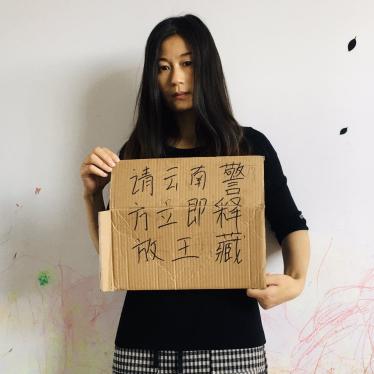

Scholars from China detailed being directly threatened outside the country by Chinese officials to refrain from criticizing the Chinese government in classroom lectures or other talks.

Others described students from China remaining silent in their classrooms, fearful that their speech was being monitored and reported to Chinese authorities by other students from China. One student from China at a university in the United States summed up his concerns about classroom surveillance, noting: “This isn’t a free space.” Drew Pavlou, a student at the University of Queensland who has been critical of the school’s ties to the Chinese government, is facing suspension on the grounds that his activism breached the university’s code of conduct.[33]

Some universities in the United States are now under pressure from federal authorities to disclose any ties between the schools or individual scholars and Chinese government agencies, with the stated objective of countering People’s Republic of China influence efforts and harassment as well as the theft of technology. Universities and scholars in Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States have been embarrassed by revelations over their ties to Chinese technology firms or government agencies implicated in human rights abuses. In April 2020 the Massachusetts Institute of Technology broke off a relationship with Chinese voice recognition firm iFlytek— whose complicity in human rights violations Human Rights Watch documented — after adopting tighter guidelines on partnerships.[34]

Other schools have grappled with tensions between students who are critical of the Chinese government and those who defend it. Students from the mainland tried to shout down speakers at a March 2019 event at the University of California at Berkeley who were addressing the human rights crisis in Xinjiang, or in September when unidentified individuals threatened the Hong Kong democracy activist Nathan Law as he arrived for graduate studies at Yale.[35]

But few — if any — universities have taken steps to guarantee students and scholars from China the same access to academic freedom as others.[36] The failure to address these problems means that for some debates and research about China are arbitrarily curtailed.

Surveillance and harassment of diaspora communities by Chinese authorities is also not a new problem, but it is clear that securing a foreign passport does not guarantee the right to freedom of expression. Even leaving China has become more difficult: Beijing has worked hard in recent years to prevent certain communities from leaving the country through tactics such as denying or confiscating their passports, tightening border security to prevent Tibetans and Turkic Muslims from fleeing, and pressuring other governments from Cambodia to Turkey to forcibly return asylum seekers in violation of their obligations under international law.[37]

Since early 2017, some Uyghurs who have traveled outside China and returned, or simply remained in contact with family and friends outside the country, have found that Chinese authorities deem that conduct criminal.[38]

As a result, even individuals who have managed to leave China and obtain citizenship in rights- respecting democracies report that they are cut off from family members still inside China, are monitored and harassed by Chinese government officials, and are reluctant to criticize Chinese policies or authorities for fear of reprisals. Some feel they cannot attend public gatherings, such as talks on Chinese politics or Congressional hearings, for fear of being photographed or otherwise having their presence at those events noted. Others describe being called or receiving WhatsApp or text messages from authorities inside China telling them that if they publicly criticize the Chinese government their family members inside China will suffer.

One Uyghur who had obtained citizenship in Europe said: “It doesn’t matter where I am, or what passport I hold. [Chinese authorities] will terrorize me anywhere, and I have no way to fight that.” Even Han Chinese immigrants to countries like Canada described deep fear of the Chinese government, saying that while they are outraged by the human rights abuses in China, they worry that if they criticize the government openly, their job prospects, business opportunities, and chances of going back to China would be affected or that their family members who remain in China would be in danger.[39]

Governments have relatively weak means to push back against this kind of harassment, given that it originates largely in China. In 2018, the Federal Bureau of Investigation stepped up its outreach to Uyghurs in the United States who had been targets of Chinese government harassment, and the Uyghur Human Rights Act, adopted in June 2020, expands that work across various diaspora communities from China.[40]

Chinese authorities also seek to limit freedom of expression beyond China’s borders by censoring conversations on global platforms. In June, Zoom, a California-based company, admitted that it had — at the request of Chinese authorities — suspended the accounts of U.S.-based activists who had organized online discussions about the 1989 Tiananmen massacre.[41] While the company reinstated the accounts of people based in the United States, it said it could not refuse Chinese authorities’ demands that it obey “local law.”

Other global platforms have also enabled censorship. WeChat, a Chinese social media platform with about one billion users worldwide, 100 million of them outside China, is owned by the Chinese company Tencent.[42] The Chinese government and Tencent regularly censor content on the platform, skewing what viewers can see. Posts with the words “Liu Xiaobo” or “Tiananmen massacre” cannot be uploaded, and criticisms of the Chinese government are swiftly removed — even if those trying to post such messages are outside the country. WeChat is wildly popular for its easy functionality, but it is also a highly effective way for Chinese authorities to control what its users worldwide can see.

It also affects what politicians outside China can say to their own constituents. Politicians around the world increasingly use WeChat to communicate with Chinese speakers in their electorates. In September 2017, Jenny Kwan, a member of the Canadian parliament, made a statement regarding the Umbrella Movement in Hong Kong in which she praised the young protesters who “stood up and fought for what they believe in, and for the betterment of their society”; that statement was subsequently posted on her WeChat account — only to be deleted.[43]

It is unclear whether or how politicians in democracies are tracking Beijing’s efforts to censor their speech. As China plays an ever-more prominent role in global affairs, governments need to move swiftly to ensure that elected representatives’ ability to communicate with their constituents is not subject to Beijing’s whims.

One can no longer pretend that China’s suppression of independent voices stops at its borders.Finally, Beijing also leverages access to its market to censor companies ranging from Marriott to Mercedes Benz.[44] Chinese state television, CCTV, and Tencent, a media partner of the National Basketball Association with a five-year streaming deal worth $1.5 billion, said they would not broadcast Houston Rockets games after the team’s general manager tweeted in support of Hong Kong’s pro-democracy protesters.[45] Under pressure from Beijing, major international companies have censored themselves or staff members. Others have fired employees who have expressed views the companies perceive as critical of Beijing. It is bad enough for companies to abide by censorship restrictions when operating inside China. It is much worse to impose that censorship on their employees and customers around the world. One can no longer pretend that China’s suppression of independent voices stops at its borders.

WHAT HAPPENS IF CHINA’S POLICIES ARE NOT REVERSED

— AND WHAT TO DO

The consequences for failing to stop China’s assault on the international human rights system, and on law and practice around rights-respecting development and on the freedom of expression are simple and stark. If these trends continue unabated, the U.N. Security Council will become even less likely to take action on grave human rights crises; the fundamental underpinnings of a universal human rights system with room for independent actors will further erode; and Chinese authorities’ (and their allies’) impunity will only grow.

Serious rights-violating governments will know they can rely on Beijing for investment and loans with no conditions. People around the world will increasingly have to be careful whether they criticize Chinese authorities, even if they are citizens of rights-respecting democracies or in environments like academia, where debate is meant to be encouraged.

Chinese government conduct over the first half of 2020 — its stalling into an independent investigations into the COVID-19 pandemic, its blatant rejection of international law in deciding to impose national security legislation on Hong Kong, even its manipulation of Tiananmen commemorations for people in the United States — appears to have galvanized momentum to push back. Members of parliaments from numerous countries are calling for the appointment of a U.N. special envoy on Hong Kong, governments are pressuring Beijing over a COVID-19 cover up, and companies’ capitulation to Chinese pressure to censor are regular news items.

But this is far from creating the kind of counterweight necessary to curb Beijing’s agenda, whose threat can now be seen clearly. To protect the U.N. human rights system from Chinese government erosions, rights-respecting governments should urgently form a multi-year coalition not only to ensure that they are tracking these threats, but also to prepare themselves to respond to them at every opportunity to push back. This means nominating candidates for U.N. expert positions and calling out obstructions in the accreditation system.

This means canvassing and organizing objections to norm-eroding resolutions, and mobilizing allies to put themselves forward as candidates for the HRC or other selections made by regional blocs. China has the advantages of deep pockets and no periodic changes in government to encumber its ability to plan; democracies will struggle with both. But here the stakes could not be higher — not just for the 1.4 billion people in China, but for people around the world.

Governments, especially those that have joined the AIIB, should use their joint leverage to push the institution to adopt well-established human rights and environmental principles and practices to ensure abuse-free development. And governments entering into BRI partnerships should carefully consider the consequences and ensure that they do what China will not: provide adequate public consultation, and full transparency about the financial implications for the country, and the ability of affected populations to reject these development projects.

Governments should urgently consider Beijing’s threats to the freedom of expression in their own countries. They should track threats to citizens, and pursue accountability to the fullest extent through tools like targeted sanctions. Academic institutions should not content themselves merely with better disclosure policies about interactions with Chinese government actors, they need urgently to ensure that everyone on their campuses has equal access to freedom of expression — any less is a gross rejection of their responsibilities.

Companies have a role to play in rejecting censorship. They should recognize that they cannot win playing Beijing’s game, especially given their responsibility to respect human rights under the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights. They should draft and promote codes of conduct for dealing with China that prohibit participation in or facilitation of infringements of the right to free expression, information, privacy, association, or other internationally recognized human rights. Strong common standards would make it more difficult for Beijing to ostracize those who stand up for basic rights and freedoms. Consumers and shareholders would also be better placed to insist that the companies not succumb to censorship as the price of doing business in China, and that they should never benefit from or contribute to abuses.

Finally, it is critical that none of these efforts to limit the Chinese government’s threats to human rights rebound on people across China or of Chinese descent around the world. The rapid spread of COVID-19 triggered a wave of racist anti-Asian harassment and assaults, and an alarming number of governments, politicians, and policies are falling into Beijing’s trap of conflating the Chinese government, the Chinese Communist Party, and people from China.[46] They are not the same, and the human rights of people in China should remain at the core of future policies.

REFERENCES

- “UN Treaty Body Database: China,” United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner, https:// tbinternet.ohchr.org/_layouts/15/TreatyBodyExternal/Treaty.aspx?CountryID=36&Lang=EN.

- Kenneth Roth, “China’s global threat to human rights,” (Washington, DC: Human Rights Watch, 2020), https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2020/country-chapters/global.

- “The Costs of International Advocacy: China’s Interference in United Nations Human Rights Mechanisms,” (New York: Human Rights Watch, September 5, 2017), https://www.hrw.org/report/2017/09/05/costs- international-advocacy/chinas-interference-united-nations-human-rights; Ted Piccone, “China’s long game on human rights at the United Nations,” (Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution, September 2018), https:// www.brookings.edu/research/chinas-long-game-on-human-rights-at-the-united-nations/.

- Ted Piccone, “China’s long game on human rights at the United Nations.”

- Sarah Zheng, “Why is China resisting an independent inquiry into how the pandemic started?,” South China Morning Post, May 16, 2020, https://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy/article/3084602/why-china- resisting-independent-inquiry-how-pandemic-started.

- “Hong Kong: Beijing threatens draconian security law,” Human Rights Watch, May 2, 2020, https://www.hrw. org/news/2020/05/22/hong-kong-beijing-threatens-draconian-security-law.

- “States should oppose China’s disingenuous resolution on ‘mutually beneficial cooperation,’” Human Rights Watch, June 16, 2020, https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/06/16/states-should-oppose-chinas-disingenuous- resolution-mutually-beneficial-cooperation.

- John Fisher, “China’s ‘win-win’ resolution is anything but,” Human Rights Watch, March 5, 2018, https://www. hrw.org/news/2018/03/05/chinas-win-win-resolution-anything.

- “The role of technical assistance and capacity-building in fostering mutually beneficial cooperation in promoting and protecting human rights,” United Nations Human Rights Council, https://www.ohchr.org/EN/ HRBodies/HRC/AdvisoryCommittee/Pages/TheRoleTechnicalAssistance.aspx.

- Andrea Worden, “China’s win-win at the UN Human Rights Council: Just not for human rights,” Sinopsis, May 28, 2020, https://sinopsis.cz/en/worden-win-win/.

- “UN: China blocks activists, harasses experts,” Human Rights Watch, September 5, 2017, https://www.hrw. org/news/2017/09/05/un-china-blocks-activists-harasses-experts.

- “UN: China responds to rights review with threats,” Human Rights Watch, April 1, 2019, https://www.hrw. org/news/2019/04/01/un-china-responds-rights-review-threats.

- “UN: Rights body needs to step up on Xinjiang abuses,” Human Rights Watch, March 12, 2020, https:// www.hrw.org/news/2020/03/12/un-rights-body-needs-step-xinjiang-abuses.

- “UN: Unprecedented joint call for China to end Xinjiang abuses,” Human Rights Watch, July 10, 2019, https://www.hrw.org/news/2019/07/10/un-unprecedented-joint-call-china-end-xinjiang-abuses.

- Sophie Richardson, “Unprecedented UN critique of China’s Xinjiang policies,” Human Rights Watch, November 14, 2019, https://www.hrw.org/news/2019/11/14/unprecedented-un-critique-chinas-xinjiang- policies.

- Louis Charbonneau, “China’s great misinformation wall crumbles on Xinjiang,” Human Rights Watch, November 20, 2019, https://www.hrw.org/news/2019/11/20/chinas-great-misinformation-wall-crumbles- xinjiang.

- “Procedural vote blocks holding of Security Council meeting on human rights situation in Syria, briefing by High Commissioner,” United Nations, March 19, 2018, https://www.un.org/press/en/2018/sc13255.doc.htm.

- UN fails to take action on order against Myanmar on Rohingya,” Al Jazeera, February 4, 2020, https://www. aljazeera.com/news/2020/02/fails-action-order-myanmar-rohingyas-200205020402316.html.

- “View country visits of special procedures of the Human Rights Council since 1998: China,” United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner, https://spinternet.ohchr.org/ViewCountryVisits. aspx?visitType=all&country=CHN&Lang=en; “Thematic Mandates,” United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner, https://spinternet.ohchr.org/ViewAllCountryMandates.aspx?Type=TM&lang=en.

- “Human rights by country: China,” United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner, https:// www.ohchr.org/EN/countries/AsiaRegion/Pages/CNIndex.aspx.

- “Report of the Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights on his mission to China,” United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner, https://ap.ohchr.org/documents/dpage_e.aspx?si=A/ HRC/35/26/Add.2; Philip Alston, “End-of-mission statement on China,” United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner, August 23, 2016, https://www.ohchr.org/en/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews. aspx?NewsID=20402&LangID=E.

- “UN experts call for decisive measures to protect fundamental freedoms in China,” United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner, June 26, 2020, https://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/ DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=26006&LangID=E.

- “China: ‘Belt and Road’ projects should respect rights,” Human Rights Watch, April 21, 2019, https://www. hrw.org/news/2019/04/21/china-belt-and-road-projects-should-respect-rights.

- Sheena Chestnut Greitens, “Dealing with demand for China’s global surveillance exports,” (Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution, April 2020), https://www.brookings.edu/research/dealing-with-demand-for-chinas- global-surveillance-exports/.

- Sophie Richardson and Hugh Williamson, “China: One belt, one road, lots of obligations,” Human Rights Watch, May 12, 2017, https://www.hrw.org/news/2017/05/12/china-one-belt-one-road-lots-obligations.

- “’We’re Leaving Everything Behind’: The Impact of Guinea’s Souapiti Dam on Displaced Communities,” (New York: Human Rights Watch, April 2020), https://www.hrw.org/report/2020/04/16/were-leaving-everything- behind/impact-guineas-souapiti-dam-displaced-communities.

- Neelam Deo and Amit Bhandari, “The intensifying backlash against BRI,” Gateway House, May 31, 2018, https://www.gatewayhouse.in/bri-debt-backlash/.

- Yun Sun, “China’s debt relief for Africa: Emerging deliberations,” The Brookings Institution, June 9, 2020, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/africa-in-focus/2020/06/09/chinas-debt-relief-for-africa-emerging- deliberations/.

- Maya Wang, “Pakistan Cares About the Rights of All Muslims—Except Those Oppressed by its Ally, China,” Newsweek, April 17, 2019, https://www.newsweek.com/china-muslims-pakistan-imran-khan-1399044.

- Nick Cumming-Bruce, “China Rebuked by 22 Nations Over Xinjiang Repression,” The New York Times, July 10, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/10/world/asia/china-xinjiang-rights.html.

- “China: New bank’s projects should respect rights,” Human Rights Watch, June 24, 2016, https://www.hrw. org/news/2016/06/24/china-new-banks-projects-should-respect-rights.

- “China: Government threats to academic freedom abroad,” Human Rights Watch, March 21, 2019, https://www.hrw.org/news/2019/03/21/china-government-threats-academic-freedom-abroad; Sheena Chestnut Greitens and Rory Truex, “Repressive experiences among China scholars: New evidence from survey data,” The China Quarterly 242, (June 2020): 349-375, https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/ china-quarterly/article/repressive-experiences-among-china-scholars-new-evidence-from-survey-data/ C1CB08324457ED90199C274CDC153127.

- Tim Swanston, “Drew Pavlou, critic of University of Queensland’s links to Chinese Government bodies, suspended for two years,” ABC News (Australia), May 29, 2020, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-05-29/ drew-pavlou-suspended-university-queensland/12302350.

- Will Knight, “MIT cuts ties with a Chinese AI firm amid human rights concerns,” Wired, April 21, 2020, https://www.wired.com/story/mit-cuts-ties-chinese-ai-firm-human-rights/; “China: Voice biometric collection threatens privacy,” Human Rights Watch, October 22, 2017, https://www.hrw.org/news/2017/10/22/china- voice-biometric-collection-threatens-privacy.

- Sophie Richardson, “The Chinese Government Cannot Be Allowed to Undermine Academic Freedom,” Human Rights Watch, November 8, 2019, https://www.hrw.org/news/2019/11/08/chinese-government- cannot-be-allowed-undermine-academic-freedom.

- “Resisting Chinese Government Efforts to Undermine Academic Freedom Abroad: A Code of Conduct for Colleges, Universities, and Academic Institutions Worldwide,” Human Rights Watch, https://www.hrw.org/sites/ default/files/supporting_resources/190321_china_academic_freedom_coc_0.pdf.

- “One passport, two systems,” (New York: Human Rights Watch, July 2015), https://www.hrw.org/ report/2015/07/13/one-passport-two-systems/chinas-restrictions-foreign-travel-tibetans-and-others; “Thailand: More Uighurs face forced return to China,” Human Rights Watch, March 21, 2014, https://www.hrw. org/news/2014/03/21/thailand-more-uighurs-face-forced-return-china.

- “’Eradicating Ideological Viruses’: China’s Campaign of Repression Against Xinjiang’s Muslims,” (New York: Human Rights Watch, September 2018), https://www.hrw.org/report/2018/09/09/eradicating-ideological- viruses/chinas-campaign-repression-against-xinjiangs.

- Yaqiu Wang, “Why Some Chinese Immigrants Living in Canada Live in Silent Fear,” Human Rights Watch, March 4, 2019, https://www.hrw.org/news/2019/03/04/why-some-chinese-immigrants-living-canada-live- silent-fear.

- Edward Wong, “Uighur Americans Speak Against China’s Internment Camps. Their Relatives Disappear,” The New York Times, October 18, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/18/world/asia/uighur-muslims-china- detainment.html.

- Yaqiu Wang, “China’s Zoom bomb,” Human Rights Watch, June 16, 2020, https://www.hrw.org/ news/2020/06/16/chinas-zoom-bomb.

- Yaqiu Wang, “How China’s censorship machine crosses borders — and into Western politics,” Human Rights Watch, February 20, 2019, https://www.hrw.org/news/2019/02/20/how-chinas-censorship-machine-crosses- borders-and-western-politics.

- Ibid.

- Kenneth Roth, “China’s global threat to human rights.”

- Kenneth Roth, “For NBA’s quandary over China, stand with human rights,” Human Rights Watch, October 8, 2019, https://www.hrw.org/news/2019/10/08/nbas-quandary-over-china-stand-human-rights.

- “Covid-19 Fueling Anti-Asian Racism and Xenophobia Worldwide,” Human Rights Watch, May 12, 2020, https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/05/12/covid-19-fueling-anti-asian-racism-and-xenophobia-worldwide