December 10 is Human Rights Day – the 72nd anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. And it also marks a grim milestone – the second anniversary of the arrests of Canadians Michael Kovrig and Michael Spavor in China. Their detention is effectively hostage diplomacy, in apparent retaliation for Canadian authorities’ arrest of the Huawei executive Meng Wanzhou on a US extradition warrant.

To Australians, this sounds disturbingly familiar. China has detained Australians on national security grounds with scant information about the crimes they are alleged to have committed. Six weeks after Chinese authorities arrested Kovrig and Spavor, Chinese officials detained an Australian writer, Dr Yang Hengjun. This August, the Chinese authorities seized an Australian journalist Cheng Lei, a business news anchor for a Chinese state media outlet, on suspicion of “endangering national security.”

In September, weeks after Cheng’s detention, the Australian government helped two journalists leave after a five-day diplomatic standoff, during which the journalists sheltered in diplomatic compounds in Beijing and Shanghai. Both were able to leave the country only after the Chinese police questioned them.

Amidst these events, the Australian government’s policy toward China has been principled and surprisingly vocal, especially when compared with Australia’s usual “quiet diplomacy” approach toward its Asian neighbors.

Government travel advice for China bluntly warns: “Authorities have detained foreigners because they're 'endangering national security.' Australians may also be at risk of arbitrary detention.”

In August 2019, Australia’s Foreign Minister Marise Payne called out the “harsh conditions” in which Yang had been held “without charge for more than seven months. … China has not explained the reasons for Dr Yang's detention, nor has it allowed him access to his lawyers or family visits. … I will continue to advocate strongly on behalf of Dr Yang to ensure a satisfactory explanation of the basis for his arrest, that he is treated humanely, and that he is allowed to return home.”

In response to China’s serious and worsening human rights violations, Australia has joined other countries in raising rights concerns about China at the United Nations. Canberra has publicly called on Beijing to address abuses in Hong Kong and Xinjiang. And Australia led the call for an independent investigation into the origins of Covid-19, particularly sensitive as Beijing has censored information and misled the Chinese public about the virus’ origins.

Australia’s newfound willingness to call out China’s myriad human rights violations has clearly been felt in Beijing, which has retaliated through angry public statements and economic actions.

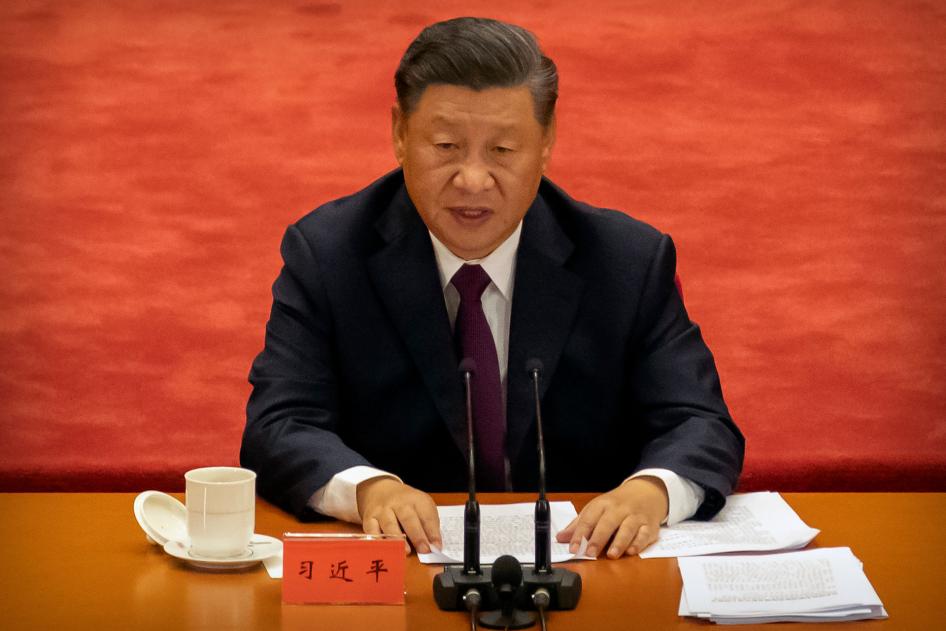

Previously, the Australian government had gone out of its way to praise its largest trading partner, with ministers dutifully regurgitating Chinese Communist Party talking points lauding Beijing’s achievement in lifting millions out of poverty. The Australian government even invited President Xi Jinping to address parliament in 2014. The focus on the economic relationship meant human rights were relegated to the sidelines, a matter for “dialogues” between mid-level bureaucrats rather than for heads of state and foreign ministers.

Australia’s attitude began to shift after Beijing started interfering in Australia’s political system. In 2018, Australia’s parliament enacted new laws to criminalize foreign interference, limit foreign donations to political parties, and require foreign political organizations or entities engaged in lobbying to register.

At the same time, Australian media exposed the brazen reach of Chinese authorities and their proxies in Australia via China’s national “anti-corruption” drive Operation Foxhunt as well as through surveillance at Australian universities and threats to diaspora communities, especially ethnic Uighurs.

China responded to Australian assertiveness not only with dubious arrests of its citizens, but by restricting Australian exports or imposing tariffs, starting with beef and barley and more recently lobster, wine, copper, sugar, timber, and coal. Some Australian state premiers and business leaders have criticized the government’s more assertive approach.

In November, Chinese diplomats leaked a document listing 14 “grievances” with Australia. The list includes the foreign interference legislation; revoking visas of China scholars suspected of endangering national security; funding “anti-China” think tanks; criticizing China’s abuses in Xinjiang, Tibet and Taiwan; calling for an independent investigation into the origins of Covid-19; and banning the Chinese technology company Huawei from the 5G network.

Shortly after the document was leaked, China's Foreign Ministry spokesman Zhao Lijian said "The Australian side should reflect on this seriously, rather than shirking the blame and deflecting responsibility."

If Australia and Canada are to resist China’s bullying tactics, they need to stand together with other principled democracies in defense of human rights. That means both vocally opposing repression inside China, and China’s efforts to undermine respect for human rights abroad and in international institutions.

The good news is this is already beginning, but more can be done to expand and strengthen this effort. In October, Australia and Canada joined 37 other countries in expressing grave concern about the human rights situation in Xinjiang and recent developments in Hong Kong. The next step should be broadening that alliance and pressing for dedicated United Nations monitoring and reporting on China’s human rights violations. Concerned countries should jointly impose targeted sanctions including travel bans and asset freezes on specific Chinese officials implicated in serious rights violations, as the US has done.

Hostage diplomacy is a serious enough global problem that in September, Australia, Canada and 33 other countries stated at the UN that they were “deeply disturbed by politically motivated arbitrary arrest, detention and sentencing of foreign nationals.” This is a good start, but for UN statements to have real impact, they need to move beyond the realm of Geneva and name the countries responsible, including powerful ones such as China. The lives of foreign citizens arbitrarily detained abroad depends on it.