(São Paulo, May 31, 2021) –The attorney general for the Brazilian state of Rio de Janeiro should fully investigate the civil and criminal responsibility of civil police commanders for extensive human rights abuses during the most lethal police raid in the history of the state, which caused 28 deaths on May 6, 2021, Human Rights Watch said today.

The operation in Jacarezinho, an impoverished neighborhood in Rio de Janeiro, resulted in the deaths of 27 residents, including a 16-year-old child, and one police officer.

“The Jacarezinho operation was a disaster that has brought enormous pain to the families of the 27 victims, as well as a police officer,” said José Miguel Vivanco, Americas director at Human Rights Watch. “The Rio de Janeiro Attorney General’s Office should thoroughly investigate not only the officers directly involved in the raid, but also civil police commanders who planned and initiated it, and ensure full accountability for abuses and the apparent destruction of crime scene evidence.”

Human Rights Watch examined police, hospital and judicial records, witness testimony, and photos and videos of corpses, and found credible evidence of serious human rights abuses. Several witnesses said police executed at least three suspects; four detainees said police beat them; and there are multiple pieces of evidence indicating that officers removed bodies from the crime scene to destroy evidence.

Among other possible violations of the law, prosecutors’ investigations should address whether civil police commanders who ordered the operation complied with a Supreme Court ruling that prohibited the police, under penalty of “civil and criminal liability,” from conducting raids in low-income neighborhoods in Rio de Janeiro during the Covid-19 pandemic, except in “absolutely exceptional cases.”

Prosecutors said the objective of the operation was to carry out arrest warrants for 21 people charged with conspiracy to engage in drug trafficking. The only evidence in the charging document, which Human Rights Watch reviewed, is photographs posted on social media that, prosecutors said, show the suspects with guns and drugs. The document describes the suspects as low-level gang members.

Although the Supreme Court did not spell out what could be considered “absolutely exceptional cases,” a high-risk, large-scale operation to detain low-level members of a drug gang does not reasonably fall into that category, Human Rights Watch said.

Under Brazilian law, the civil police investigate whether their members committed any abuses in the operation. This system does not meet the necessary requirements for an independent and impartial criminal investigation, Human Rights Watch said.

The head of the civil police homicide department, the unit in charge of the investigation, said on the day of the operation that “no execution” had taken place. He spoke even before police officers had given their initial statements to police investigators, which Human Rights Watch reviewed. Later, the chief of civil police stated that “Rio is much safer with these 27 criminals eliminated,” referring to the people killed by police.

Initial investigative steps by civil police have been woefully inadequate. About 200 civil police officers were involved in the raid, but civil police investigators only took statements from 29 on the day of the operation and did not question them individually, but in groups of two or more. The statements are cursory, in many cases just five lines long.

Police records show that civil police investigators seized only 26 police weapons for ballistic analysis on the day of the shootings and they only mention that forensic analysis was carried out at the sites of three of the 27 killings by police.

While civil police investigate all crimes in Brazil, prosecutors can also open their own investigations. The state attorney general announced on May 11 that he had set up a working group of four prosecutors to investigate the killings.

Prosecutors should conduct a fully independent investigation, Human Rights Watch said, including by having forensic experts who are independent of the civil police conduct their own analysis of the evidence. Prosecutors should also interview all witnesses and victims, who may understandably fear talking to civil police investigators about abuses committed by their colleagues.

A working group led by federal prosecutors in Rio de Janeiro asked the Rio attorney general to call on federal police to assist in the investigation to ensure its independence, and urged closing the civil police investigation. The Rio Attorney General’s Office rejected the recommendation.

The Rio Attorney General’s Office should investigate not only police officers or others directly involved in crimes committed during the raid, but also police commanders who planned and executed the Jacarezinho raid, and the chief of civil police of Rio de Janeiro, Human Rights Watch said. In particular, the office should examine commanders’ possible criminal and civil responsibility for actions or omissions both before, during, and after the operation, including likely destruction of key evidence. The prosecutors should also investigate whether commanders properly evaluated the risk to police officers who participated in the operation.

The Rio Attorney General´s Office told Human Rights Watch it had opened a civil investigation into whether civil police had failed to comply with the Supreme Court ruling prohibiting raids.

Federal prosecutors should also open a criminal investigation into whether commanders committed the crime of “disobedience” by not complying with the ruling. Supreme Court justice Edson Fachin called for such an investigation on May 21.

“The police should ensure people’s safety, but instead, the brutality and impunity with which they act in Rio’s poor neighborhoods make residents see them as a threat to themselves and to their children,” Vivanco said. “It is crucial for the Attorney General’s Office to defend the rights of those residents and the rule of law, and seek accountability for any abuses up to the highest levels of the police command.”

For further information on the Jacarezinho raid, please see below.

Supreme Court Decision to Prohibit Police Raids

On June 5, 2020, Brazil’s Supreme Court prohibited both civil and military police from conducting raids in low-income neighborhoods in Rio de Janeiro state during the Covid-19 pandemic, except in “absolutely exceptional cases.” From June through September 2020, police killings dropped by 72 percent, compared with the same period in 2019. The number of other homicides also fell by 20 percent during that period.

In September, the chief of civil police, Allan Turnowski, told the media that the court’s decision did not preclude police operations because the level of violence in Rio de Janeiro made the situation in the state “exceptional.” Turnowski also said he intended to request equipment from the army to conduct military-style raids in poor neighborhoods and ensure “war superiority.”

In October, the number of killings by police started going up again, as police increased the number of operations despite the court’s ruling. From January through April 2021, civil and military police killed 595 adults and children, the second-highest death toll, after 2020, for any January-April period since Rio de Janeiro state started collecting police killings data in 2003.

The court also ordered that in “absolutely exceptional cases” when raids were carried out, police adopt “extraordinary care” to prevent endangering the population and public health services. The Jacarezinho raid forced Covid-19 vaccination sites in the neighborhood to close temporarily.

At a news conference after the Jacarezinho raid, Rodrigo Oliveira, the chief of police operations, said that “judicial activism” impeded or made it more difficult for the police to act in some areas and claimed, without providing evidence, that as a result drug trafficking organizations have become stronger.

The Rio de Janeiro Attorney General’s Office should investigate whether Rio police violated the requirements of the Supreme Court decision, in the context of a civil investigation into “administrative misconduct,” Human Rights Watch said. Federal prosecutors should also investigate whether commanders committed the crime of “disobedience” by not complying with the court order.

Civil and Criminal Investigation of Commanders by State Prosecutors

Under Brazilian law, prosecutors can conduct civil investigations into commanders’ “administrative misconduct.” Brazilian law defines that offense as “any act or omission that violates the duties [of public servants] of honesty, impartiality, legality, and loyalty to institutions.” In particular, it cites “carrying out an action whose objective is prohibited by law” and “to improperly delay or not carry out a required official action.” Administrative misconduct is punished with dismissal, fines, and other penalties.

The Group of Specialized Action in Public Security (GAESP, in Portuguese), a unit of prosecutors in Rio state specializing in police abuse cases, opened two such investigations against civil police officers. One looked into their role in a 2019 raid at Complexo da Maré neighborhood during which a police helicopter fired 480 times near schools. The other examined the killing of 14-year-old João Pedro during a 2020 operation in São Gonçalo. The Rio attorney general dissolved GAESP in March and the two civil investigations were assigned to other prosecutors and are pending.

Brazilian law also permits prosecutors to open criminal investigations into police commanders, if the evidence warrants it, for “malfeasance,” which punishes public servants for failing to properly carry out their duties “due to personal interest or disposition,” with up to one year in prison.

Official Explanations of the Jacarezinho Raid

In the early morning of May 6, 2021, civil police deployed about 200 heavily armed officers in Jacarezinho, supported by at least one helicopter and armored vehicles. The hours-long raid, brought the vast neighborhood of narrow alleys to a standstill, forcing stores to close, and making residents run for cover and lock themselves in their homes in fear. Some later spoke with representatives of the Public Defender’s Office and the Rio Bar Association about the horror they felt, not only at seeing the dead, but also at hearing police at the scene making jokes about the victims.

The Supreme Court ruling mandated police to inform Rio de Janeiro’s attorney general “immediately” of any raid and explain in writing why it was an “absolutely exceptional case.” Civil police told the Attorney General’s Office about the Jacarezinho raid three hours after it had started. Police said the raid was the result of intense planning and 10 months of investigation, but did not explain why they did not inform the Attorney General’s Office much earlier.

In a news release and a news conference the day of the operation, civil police claimed that the objective of the raid, led by its crimes against children unit, was to detain gang members whom they accused of homicides, recruiting children to sell drugs, and other crimes. In a letter sent to the federal attorney general after the operation, however, the chief of civil police said that the raid was aimed at executing arrest warrants against 21 people, who were sought for “conspiracy to commit drug trafficking,” but did not mention any of the other alleged crimes. The Rio Attorney General’s Office also said the objective was to arrest those 21 suspects, whom the charging document describes as low-level members of a drug gang. Police detained three of them during the raid; and killed another three.

Police told the media that 22 other victims —who were not on the list of suspects to be arrested— had been arrested for various alleged crimes at least once previously, although the police did not explain if they had been convicted of a crime. Two other victims, including a 16-year-old child, had never been arrested.

Evidence of Executions, Detainee Abuse

There is credible evidence of serious police abuses during the raid.

A man arrested in the operation later told a judge that police executed two people in front of him and two other witnesses, according to a summary of his statement written by a public defender present at the hearing that Human Rights Watch reviewed. Another man said that police executed another person, who was unarmed, in his daughter’s room. Human Rights Watch reviewed a statement another witness made to the Human Rights Commission of the Rio de Janeiro Bar Association that corroborates that account.

At least one of the 27 victims was shot in the back, based on hospital records Human Rights Watch reviewed.

At an arraignment hearing, four detainees told a judge that at the time of arrest police slapped them, stepped on them, kicked them, and beat them with their weapons, leaving swollen eyes, bruises and other visible marks on three of them, said the Public Defender’s Office, who represents them. At least one detainee said he was also beaten at the police station while police took his statement.

Destruction of Evidence

In its 2020 decision, the Supreme Court ordered law enforcement and health personnel to preserve all evidence of crimes during police operations and to “prevent the inappropriate removal of corpses under the pretext of alleged rescue, and the destruction of elements and objects that are important for the investigation.”

For years, Human Rights Watch has documented that Rio police often take the dead bodies of victims of police shootings to the hospital, claiming they were still alive when first transported, as a ruse to destroy crime scene evidence. The evidence strongly suggests similar actions during the Jacarezinho raid.

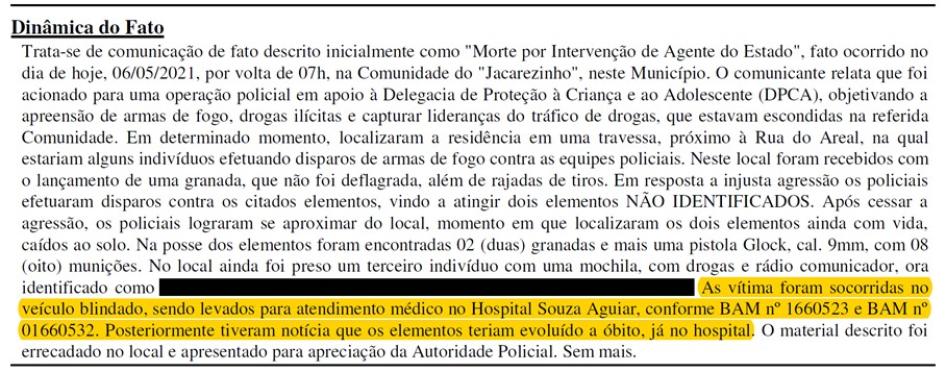

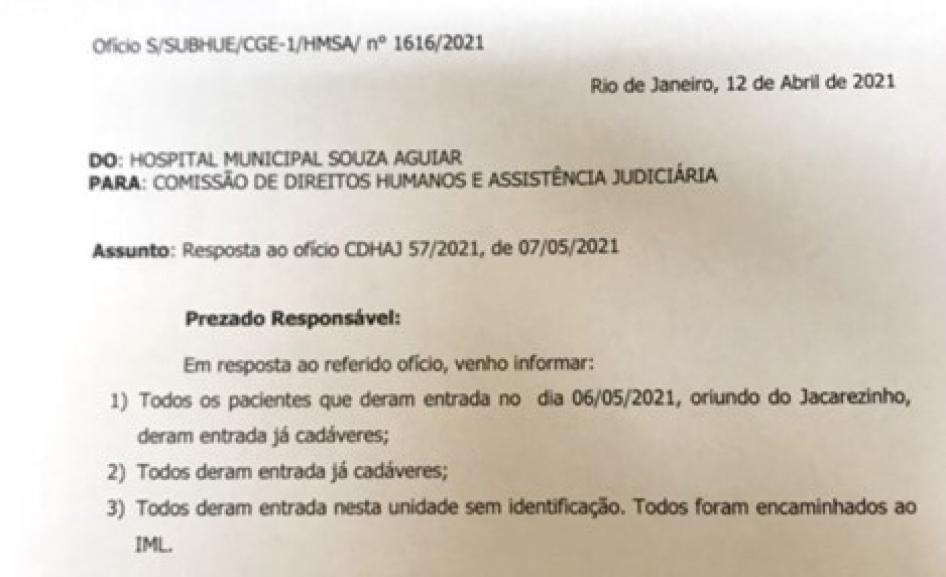

Police took 25 of the 27 victims to hospitals, where they arrived dead, according to the Public Defender’s Office, which obtained hospital and police records.

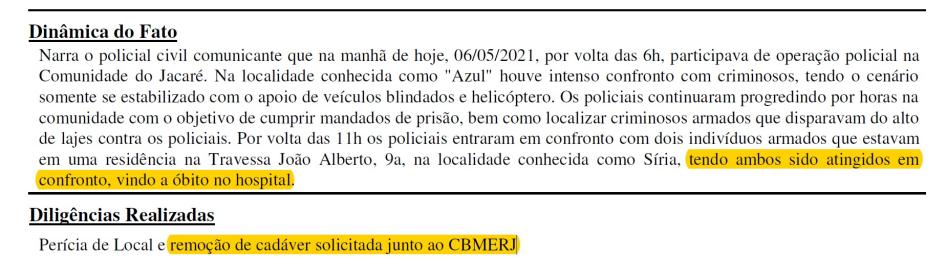

In their statements to civil police investigators, reviewed by Human Rights Watch, 18 civil police officers involved in the killings said that police took 16 injured victims to the hospital.

If they were indeed alive, police should have called the state’s emergency health services or the firefighters and have them take the injured to the hospital, as Rio state law requires. In “extreme cases,” police can take an injured person to the hospital, but they should ask a relative or witness to go with them, the law says. There is no police record or statement showing that they complied with that requirement.

In two cases, firefighters were called for “removal of corpse” from the site, according to a statement by a police officer. But contradicting himself, the same officer said in the same statement that the victims were injured and died “at the hospital.”

The police statements do not say what police did with the remaining 9 people they shot.

Four of the 27 people shot by police died “at the hospital,” according to the statements of five police officers involved in the shootings. But those statements contradicted the three hospitals where victims were taken, which said that all victims arrived dead.

Police officers did not specify where the other 23 people shot by police died. The only shooting victim who was alive when he arrived at the hospital was a police officer, who later died there, press reports said.

Human Rights Watch reviewed hospital records for five of those who died, all of which described severe injuries, including a man whose face was “completely mangled.”

At least four detainees told a judge that police forced them to take dead bodies into armored vehicles, also contradicting the police claims that all victims were alive. Two detainees said they carried about 10 bodies into police vehicles, according to a recording of their hearing, which Human Rights Watch reviewed.

Residents of Jacarezinho also said they saw police carrying dead bodies. Photos and videos recorded by residents that the Rio Bar Association provided to Human Rights Watch appear to show several dead bodies lying motionless on the ground, over pools of blood, including a man whose face is covered in blood. The photos and videos show the bodies on their own, without any police or health personnel.

Prosecutors should investigate whether police officers committed any offenses, including the crime of procedural fraud, by destroying crime scene evidence, Human Rights Watch said.

Flawed Civil Police Investigation

The civil police investigation has had serious flaws. On the day of the raid, civil police investigators wrote 12 “incident reports”—documents police write when a person reports a fact that may need to be investigated—about the 27 killings by police. The reports included statements about the killings taken by investigators and investigative steps adopted.

The incident reports show investigators took statements from only 29 officers, about 14 percent of those involved in the raid, and the statements lack crucial information such as where victims died. One statement taken from nine officers at the same time reports seven killings but does not even say how the victims died.

Incident reports also show that civil police investigators only seized 26 police weapons for ballistic analysis on the day of the shootings.

The reports state that forensic analysis was conducted at two shooting sites where police killed a total of three people. They do not mention crime scene analysis at any of the other 11 locations where 24 other people were killed.

Members of the Public Defender’s Office and of the Rio Bar Association visited Jacarezinho in the afternoon of the raid and saw that police had not preserved the crime scenes, both organizations told Human Rights Watch. Brazilian law and international standards require the police to isolate and preserve the sites of deadly shootings for forensic analysis.

The Public Defender’s Office said that, to its knowledge, police detained six people during the raid. Three of them were among the 21 suspects the raid was intended to apprehend and another two had pending arresting warrants in other cases. Four of them were charged with possession of drugs at the time of their arrest, but the Public Defender’s Office said that the forensic expert who received the alleged drugs for analysis reported that the chain of custody was not maintained, as the drugs were not preserved in a sealed police bag with adequate identification.

Secrecy

Days after the killings, Brazilian media requested information from Rio’s civil police through the Access to Information Law. Several outlets requested the names of all the officers involved in the Jacarezinho raid; the communication civil police sent to the Rio Attorney General’s Office informing it of the raid; and the police report detailing what happened in the operation. The civil police command not only rejected the petitions but, after receiving the requests, classified the information for five years, contending that publication would endanger strategic police operations and criminal investigations.

The civil police command also denied a media request for the list of all operations in impoverished neighborhoods carried out since the June 5, 2020 Supreme Court ruling and the justification for considering them “absolutely exceptional cases.” The civil police command also contended that the information would put strategic operations at risk and classified it for five years.

Brazil’s Access to Information Law establishes that the authorities may not restrict access to information about violations of human rights. Access to information from public bodies is also protected under international human rights standards, as an aspect of freedom of expression that is essential to democratic accountability. In cases involving human rights abuses, access to information can be critical to ensuring accountability for abuses.

Without a detailed explanation as to why such extensive secrecy is both a necessary and proportionate restriction on the right to access to information, the decision to withhold important information about the Jacarezinho investigation and other operations for five years looks like an attempt to conceal information from public scrutiny, Human Rights Watch said. An independent authority should review the decision to classify the information.