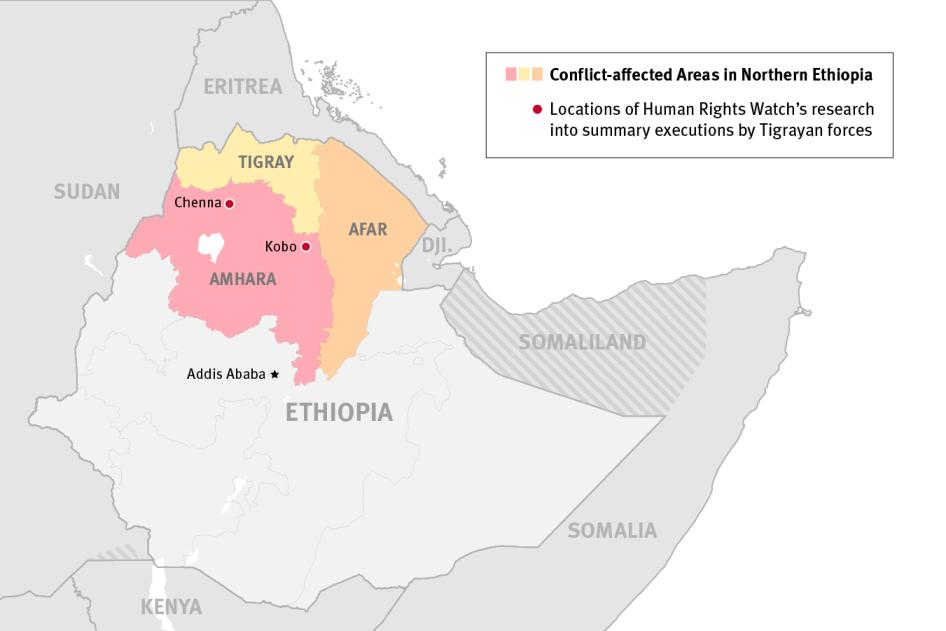

(Nairobi) – Tigrayan forces summarily executed dozens of civilians in two towns they controlled in Ethiopia’s northern Amhara region between August 31 and September 9, 2021, Human Rights Watch said today. These killings highlight the urgent need for the United Nations Human Rights Council to establish an international investigative mechanism into abuses by all warring parties in the expanded Tigray conflict.

On August 31, Tigrayan forces entered the village of Chenna and engaged in sporadic and at times heavy fighting with Ethiopian federal forces and allied Amhara militias. Chenna residents told Human Rights Watch that over the next five days Tigrayan forces summarily executed 26 civilians in 15 separate incidents, before withdrawing on September 4. In the town of Kobo on September 9, Tigrayan forces summarily executed a total of 23 people in four separate incidents, witnesses said. The killings were in apparent retaliation for attacks by farmers on advancing Tigrayan forces earlier that day.

“Tigrayan forces showed brutal disregard for human life and the laws of war by executing people in their custody,” said Lama Fakih, crisis and conflict director at Human Rights Watch. “These killings and other atrocities by all sides to the conflict underscore the need for an independent international inquiry into alleged war crimes in Ethiopia’s Tigray and Amhara regions.”

Since the start of the armed conflict in Ethiopia’s northern Tigray region in November 2020, Ethiopian military forces, alongside Eritrean armed forces, Amhara regional special forces, and Amhara militias, have fought against a Tigrayan armed group affiliated with the region’s former ruling party, the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF). Human Rights Watch and other rights organizations have documented war crimes and possible crimes against humanity in the Tigray region by all parties to the conflict. In July, fighting expanded to the neighboring Amhara region, leading to large-scale displacement, with 3.7 million people in the region in need of humanitarian assistance.

In September and October, Human Rights Watch remotely interviewed 36 people, including witnesses to killings, victims’ relatives and neighbors, religious figures, and doctors about fighting and abuses in and around Chenna Teklehaimanot village (Chenna) and the town of Kobo. Nineteen people described seeing Tigrayan fighters in Chenna and Kobo summarily execute a total of 49 people who they said were civilians, providing 44 names.

Human Rights Watch also obtained three lists of civilians who had allegedly been killed in Chenna between August 31 and September 4. Taken together, the lists contain 74 names, 30 of which witnesses and relatives of those killed also mentioned to Human Rights Watch. In addition to summary executions, civilians may also have been killed during the fighting from crossfire or heavy weapons. Human Rights Watch was not able to determine how many were killed in this way.

A 70-year-old man said that two Tigrayan fighters killed his son, 23, and nephew, 24, in his home in Chenna’s Agosh-Mado neighborhood on September 2: “At about midday two Tigrayan fighters came to my compound … they asked [for] our identity cards and accused us of being members of the local defense forces. Then they tied my son and nephew’s hands behind their backs and took them out through the gate of my compound and shot them dead there. Then they turned to me, and I begged them not to kill me and they left.”

Witnesses also said that Tigrayan forces put civilians at grave risk by holding them in residential compounds and shooting from those compounds at Ethiopian troops positioned on nearby hills, drawing return fire. Such actions may amount to “human shielding,” a war crime.

Tigrayan forces seized control of Kobo in North Wollo district in mid-July. According to residents of Kobo and nearby villages, on the morning of September 9, Tigrayan forces from Kobo conducted operations in neighboring villages. As these forces searched for weapons in at least two villages, farmers there attacked the Tigrayan forces and fighting ensued. When Tigrayan forces returned to Kobo shortly after midday, they attacked farmers working in the fields between the villages and Kobo.

Four residents described the summary execution of 23 people, including farmers returning to Kobo, in four incidents in the town.

A resident of Kobo’s Segno Gebia neighborhood said that at about 2 p.m. on September 9 he watched from the window of his home as Tigrayan forces executed four men. “At one point I saw about 50 Tigrayan fighters,” he said. “About five of them went into a room where you can chew qat [a popular mild stimulant] and brought out four men who were my neighbors and just shot them. I don’t know why they chose them.”

On December 4, Human Rights Watch sent TPLF authorities a summary of findings requesting comment but received no response.

The UN Human Rights Council should urgently establish an independent international mechanism to investigate abuses in the Tigray conflict, which has since expanded into the neighboring Amhara and Afar regions. The investigation should include alleged summary executions and other serious violations of the laws of war by Tigrayan forces, identify those responsible at all levels, and preserve evidence for future accountability, Human Rights Watch said.

The UN Security Council should add Ethiopia to its formal agenda and urgently take concrete measures against the warring parties to deter further abuses, including targeted sanctions and a global arms embargo.

“Tigrayan forces’ apparent war crimes in Chenna and Kobo spotlight the urgent need for all warring parties in Ethiopia to prioritize the protection of civilians,” Fakih said. “The UN Security Council needs to pressure the parties to make this happen through sanctions and an arms embargo.”

Expanding Conflict in the Amhara Region

Since the armed conflict began in Ethiopia’s Tigray region in November 2020, human rights groups and the media have documented serious laws-of-war violations by the Ethiopian military and their allied forces. Tigrayan militias have also been responsible for attacks against Eritrean refugees. Following the withdrawal of Ethiopian federal forces from most of Tigray in June, the government has imposed an effective siege on the region, blocking essential humanitarian aid and services.

By July, Tigrayan forces had moved into neighboring Afar and Amhara regions, displacing hundreds of thousands of civilians, some multiple times, and triggering widespread humanitarian needs. Tigrayan forces have also committed sexual violence against women and girls in the Amhara region. On November 4, Ethiopian federal authorities declared a state of emergency granting security forces sweeping powers, and called on the population to mobilize and join the fight against Tigrayan forces.

Tigray Forces Occupy Chenna, August 31 – September 4, 2021

Chenna is a small rural village in Dabat woreda (district), North Gondar zone in the Amhara region. Ethiopian soldiers stationed in the village left suddenly on August 30 and were replaced by a new contingent of Ethiopian forces that afternoon, residents said.

At about 4 a.m. on August 31, Tigrayan forces entered Chenna. They fought the Ethiopian military troops at close quarters for two days before the Ethiopian forces retreated from the village. On September 4, Ethiopian military forces, Amhara militias, and Amhara regional special forces retook the village.

Residents said that Tigrayan forces occupied residential compounds while in the village. Two witnesses said that these forces fired on Ethiopian forces positioned in nearby hills when no civilians were in the compounds. However, another described a situation in which Tigrayan forces forced civilians to remain in a compound, possibly using them as human shields. Two others said Tigrayan forces deployed in compounds with civilians remaining in them, putting the civilians at risk when Ethiopian forces returned fire.

Both sides used heavy weapons, including artillery, mortars, and machine guns. A man from the nearby village of Wakken, who had just completed 15 days of military training by Ethiopian soldiers when Tigrayan forces seized Chenna, said that on the morning of August 31 he joined the soldiers fighting in nearby mountains, where they exchanged fire with Tigrayan forces in Chenna. Another said that on September 2 and 3, Ethiopian forces’ use of heavy weapons, including mortars, against Tigrayan forces in Chenna was particularly intense.

Genet said that Tigrayan forces occupied her family’s large compound, firing DShK mounted machine guns at Ethiopian forces on the mountainside. She said that on September 3, Ethiopian forces fired at the compound using unspecified heavy weapons that killed some Tigrayan fighters and damaged the animal shed, killing some cows and donkeys. At one point, Tigrayan soldiers speaking Amharic and Tigrinya came to her house, she said, saying they were redeploying to her compound because Ethiopian forces had fired on their troops in the church.

Several residents said they saw Tigrayan forces occupy the villages’ main church and one said they occupied a school. Five residents said that Tigrayan forces pressured families to slaughter their cattle and cook for them in their compounds without paying. Two residents also said that Tigrayan forces made them carry supplies.

Civilians were caught in the fighting. Some Chenna villagers fought alongside government soldiers, which under the laws of war would be directly participating in the hostilities. Others carried food for the government troops or tended to the wounded, which would not subject them to attack.

Summary Execution of Civilians in Chenna

Chenna residents interviewed provided the names of 39 civilians they said Tigrayan forces summarily executed while occupying the village, although they only saw 26 of them being killed. In addition, Human Rights Watch obtained three lists of 57, 48, and 37 names, drawn up by a local official and two priests who had each overseen the funerals of about 30 people after the fighting had ended. They said the civilians on the lists were killed between August 31 and September 4, although they did not know how each person had been killed. Some names appeared on two or all three of the lists and, removing duplicates, the total number of names comes to 74. In addition, 9 names from the Human Rights Watch interviews do not appear on any of the three lists.

A doctor working at the University Hospital in Gondar city, said that injured civilians were first taken from Chenna to the nearby Dabat Hospital on September 4 and 5, and then referred to Gondar from September 6 onward. He estimated that 35 of the people referred from Dabat were civilians from Chenna, including 3 women and 3 children. Between September 6 and 11, the hospital also received more than 1,000 injured Ethiopian soldiers and civilians who had been injured while fighting in Chenna and nearby areas or otherwise assisting Ethiopian forces.

Local officials reported that between 120 and 200 civilians had been killed during the fighting, but Human Rights Watch was unable to corroborate those additional cases.

Human Rights Watch interviewed 15 people, who described 15 incidents in which Tigrayan forces summarily executed 26 civilians in Chenna between August 31 and September 4, including 22 men, 1 woman, and 3 children. Human Rights Watch corroborated 3 of these cases in which a total of 4 people were killed. In the other 12 incidents, Human Rights Watch was only able to speak with one witness.

On August 31, groups of Tigrayan fighters, hours after occupying Chenna, entered a residential compound, confiscated the food in the house, and took away a farmer and his brother. The farmer’s wife, Martha, said:

They kicked and slapped my husband and brother-in-law. They ate our food and then they left and other Tigrayan forces came for some time and left, and a third group came. They stayed until midday.

They took my husband and brother-in-law with them in the direction of Chinchaye sub-village and kicked and slapped them. I followed them and they beat me, telling me to stay behind, but I ignored them.

They spoke in Tigrinya, which I don’t understand, but also in Amharic and I heard them ask my husband and brother-in-law whether they were militia members. They said no, they were farmers. When we reached the edge of Chenchaye, they told my husband to put down a bag of bullets they had told him to carry and to turn his face away. Then one of them shot him in the back of the head. I fainted.

The fighters released the brother-in-law, but Martha added how she has not been seen or heard from him since.

Hilina said that her husband and brother-in-law were killed in apparent retaliation for her father-in-law’s participation in fighting against Tigrayan forces in Chenna. Hilina explained:

At about 2 p.m. on September 1, I was with one of my husband’s relatives close to my home in Dia sub-village. Tigrayan fighters approached and shot over her head, shouting that she should tell them whether any of her relatives had fought against them in Chenna. She told them that my brother-in-law’s father, a local militia member, had joined local farmers fighting against them. They beat her until she showed them his house.

The next day at about 11 a.m., I saw about 10 of them go to his house, very close to ours, and they found his [adult] son. They brought him out of the house and took him to the edge of a field one minute away. I heard them speaking to him in Tigrinya and Amharic and they accused him of giving information to his father about where Tigrayan fighters were in Chenna. Then one of them shot him in his abdomen, killing him.

On September 3 at about midday, my husband returned from a different area and found out that his brother had been killed. He started crying. Soon after that, Tigrayan forces came to our house, said he was the son of a militia member and took him to the Laka River about three minutes from our house, above Saint George’s church. I followed them and saw them shoot him in the abdomen, killing him.

Another woman, Eyerusalem, said that just before Tigrayan forces left Chenna on September 4, they killed her 60-year-old father and her 67-year-old grandfather’s brother:

It was about 10 a.m. on Saturday [September 4] and I was at my father’s house with him, together with my great uncle who lives right next to us in Digansa sub-village. Suddenly, Tigrayan fighters who were being pushed out of the village by Ethiopian soldiers came into our compound. They were angry that they were losing the battle. They stayed for about an hour. Just before they left, they took my father and great uncle outside the front of the compound. Two of them tied my father’s hands behind his back and then shot him. Four of them then shot my great uncle.

Two other Chenna residents said Tigrayan fighters killed two residents, whose names they provided, in two separate incidents for refusing to slaughter livestock for the fighters.

A local priest said that Tigrayan forces shot and killed his 22-year-old neighbor:

I was in my home compound with my neighbor. The Tigrayan forces kept coming in and out of my compound and told us to prepare food for them. On September 2, they beat my neighbor to force him to slaughter my goats. The next day, other fighters told him to steal other peoples’ goats and bring them to my compound and slaughter them. When he refused, they took him outside my compound and tied him to a tree and shot him in the head.

Summary Executions of Civilians in and around Kobo, September 9

The town of Kobo, in the North Wollo district of the Amhara region, has an estimated population of about 60,000. Human Rights Watch interviewed 13 displaced residents of Kobo about fighting there and in nearby villages to the east and south on September 9 and 10. They had fled to the town of Dessie, about 165 kilometers from Kobo, shortly after September 10, where they joined thousands of others who had already fled Kobo when Tigrayan forces controlled the town in mid-July. Human Rights Watch was unable to reach people by phone who were still in Kobo or the surrounding areas because the phone network had been down since then.

Four people interviewed said they had spoken with people from villages south of Kobo who had described what had happened. These people said that on September 9 between about 9 a.m. and 1 p.m., Tigrayan forces entered their villages and searched for weapons. In at least two villages, Gedemeyu and Zobel, farmers responded by attacking the Tigrayan forces, they said.

Two residents said that as Tigrayan forces retreated along the main road from the villages toward Kobo, they killed farmers in the fields. A farmer from Kobo said he heard gunshots as he worked on his land between Kobo and Gedemeyu village on September 9:

I saw Tigrayan fighters driving along the road from Kobo to Gedemeyu at about 9 a.m. At about 11 a.m., I heard gunshots and about two hours later I heard gunshots getting louder. I fled back to Kobo with many of the other farmers there, but some of the farmers stayed in their fields.

He said the next day he spoke to some of those farmers in Kobo:

They told me that as the Tigrayan forces returned on the road to Kobo, they shot at the farmers in the fields. On the next day, September 11, I went back to my land and helped recover three bodies of farmers who were lying in the fields. One of them was my cousin. We buried them that day in Saint Michaels church in Kobo. I also saw nine other bodies during their burial in Saint George’s church in Kobo that day, who people said had been killed on the farms between Kobo and Gedemeyu, too.

Tigrayan forces returned from the nearby villages to Kobo around 2 p.m. on September 9 and searched houses for weapons in various parts of Kobo, including the Buna Bank in Ketana 5, and Segno Kebeya neighborhood, two residents said.

That same day, Tigrayan forces executed 23 civilians in three neighborhoods in the city, four residents said. Local residents in Kobo told journalists they had seen dozens of corpses in the streets. Five people said they saw bodies lying in the streets that afternoon but did not know their identities.

Ahmed, a minibus driver from Kobo said:

The morning of September 9, I drove my minibus from Kobo to Weldiya village nearby and drove back to Kobo between 1 and 2 p.m., passing through the usual Tigrayan checkpoint near Kobo.

When we entered the town, we heard gunfire. We tried to reach my house, but I got stuck due to the fighting. I parked my minibus in the Segno Gabia neighborhood and went with my assistant to a local shop until about 5 p.m. The fighting died down a bit, so we tried to walk to my house.

Near my house, we saw many dead bodies on the ground including a woman. A baby was also crying on the body of another dead woman. Then we reached a major junction in the area. Tigrayan forces stopped us there. Some of them were teenagers.

I saw six people whose hands had been tied behind their backs and who were standing in a line. They were wearing civilian clothes and they didn’t have any guns.

Then one of the fighters ordered other fighters to shoot me and my assistant, but one of the fighters recognized me from a checkpoint outside Kobo I had driven through earlier that day. He said they shouldn’t shoot me because I was a driver, not a fighter. I speak Tigrinya and told them all that my assistant was also a driver, not a fighter, but one of the fighters said I was lying.

At that moment, one of the six people with their hands tied behind their back ran away and my assistant ran away too. One of the fighters then shot my assistant in the back and killed him, while the other man escaped. They shot him in the back. Then one of the fighters ordered the teenage fighters to shoot the other five men with their hands tied and they did, one by one. Then they let me go.

Another resident said that on September 9 he watched from his house in the Piassa neighborhood of Kobo as Tigrayan fighters executed 12 farmers from his neighborhood, whose names he listed, at about 4 p.m. after they had returned from their farms near Gedamayu village.

Applicable Laws of War

International humanitarian law, or the laws of war, is applicable to all parties to the armed conflict in Ethiopia’s Amhara, Afar, and Tigray regions. Under Common Article 3 to the four Geneva Conventions of 1949, captured combatants and civilians must “in all circumstances be treated humanely.” They are protected against “violence to life and person, in particular murder of all kinds, mutilation, cruel treatment and torture.”

Under the laws of war, warring parties may target only military objectives. Deliberate attacks on civilians and civilian objects, indiscriminate attacks, and attacks that can be expected to cause disproportionate civilian harm are prohibited. Military forces can only attack civilians who are at the time directly participating in hostilities, such as by firing weapons.

Warring parties must take all feasible precautions to protect civilians under their control from the effects of attacks. This means removing civilians, to the extent feasible, from the vicinity of their forces. Deliberately deploying behind civilians to deter attacks is considered “human shielding,” a war crime.

A warring party’s seizure of private property must be justified by military necessity, and compensation must be provided. Pillage, forcibly taking private property for personal use, is prohibited and can constitute a war crime. Parties to a conflict must protect property, including churches and schools, that is of great importance to the country’s cultural heritage.

People who commit serious violations of the laws of war with criminal intent – that is, intentionally or recklessly – may be prosecuted for war crimes. Individuals may also be held criminally liable for assisting in, facilitating, aiding, or abetting a war crime.

Recommendations

Tigrayan Defense Forces and all other parties to Ethiopia’s conflict in Tigray should respect international humanitarian law and immediately cease unlawful attacks against civilians. They should treat everyone in custody humanely and prohibit or prevent summary executions and other abuses. Those responsible for abuses should be appropriately punished.

The Ethiopian government should endorse the Safe Schools Declaration, an international political commitment – currently supported by 108 countries – to take concrete measures to better protect students, teachers, schools, and universities from attack during conflict, including by refraining from using schools for military purposes.

The UN Human Rights Council should hold a special session on Ethiopia and establish without undue delay an independent international mechanism to publicly report on conflict-related abuses, preserve evidence, and pave the way for credible accountability.

The UN Security Council should add Ethiopia to its formal agenda and impose targeted sanctions and a global arms embargo.