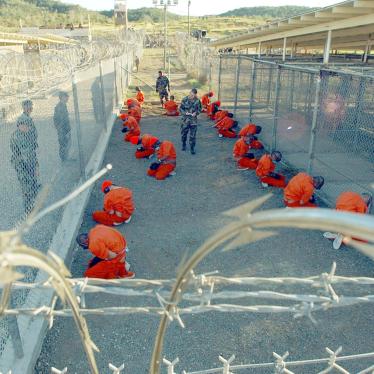

The U.S. military prison at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, may seem a world away from Florida, but it’s only 700 miles from Orlando. Growing up here myself, I never thought twice about what Guantanamo’s high financial and moral cost meant for me as a Floridian.

But after nearly a year of digging into human-rights issues, I can’t get Guantanamo out of my mind. My federal tax bill brings the issue to the forefront of my wallet too: the U.S. spends more than $540 million per year to detain fewer than 40 prisoners at Guantanamo. The true cost is surely higher since it includes classified costs.

Yet neither Congress nor the White House are focused on Guantanamo’s high price tag.

Senior Defense and State Department officials recently appeared before Congress to discuss their 2023 budget requests. Funding for Guantanamo’s prison did not come up once.

The White House has been similarly silent on Guantanamo’s cost. President Joe Biden’s 2023 budget overview also makes no mention of Guantanamo.

Should we assume that this half a billion per year is now just an assumed cost for U.S. taxpayers?

The best way to reduce Guantanamo’s cost is to close it, which President Biden has committed to doing. Yet, the president has yet to recreate an Obama-era senior State Department position to oversee Guantanamo’s closure. Actual transfers of the remaining prisoners are coming in dribs and drabs, although the Biden administration has provisionally cleared 15 detainees, bringing to 20 the number of men awaiting transfer elsewhere.

Even if the administration does succeed in transferring these 20 men, the facility’s costs could still increase. New construction at Guantanamo Bay to build a second courtroom carries a $4 million price tag. Meanwhile, aging prisoners require additional resources because of increasingly complicated medical needs — which are often compounded by abuse they suffered while detained.

In addition to its price tag, the Guantanamo prison serves as a rallying cry for armed groups like the Islamic State (ISIS) and al-Qaeda. As national security professionals note, Islamist armed groups use the treatment of Guantanamo detainees as propaganda. It’s hard to forget how ISIS dressed Western and other hostages in Guantanamo-style orange jumpsuits before executing them, in a clear message to the United States and its allies.

Guantanamo also carries a hefty moral cost for the United States. In October 2021, a U.S. military jury described one detainee’s treatment as “a stain on the moral fiber of America” in a handwritten clemency petition. The detainee, Majid Khan, remains imprisoned at Guantanamo despite completing his sentence because the U.S. has not found a safe country that will accept him.

Other than Khan, only one man still at Guantanamo has been convicted of a crime. Of the 35 other prisoners, 10 are awaiting trial for war crimes, including all five defendants charged with links to the September 11, 2001, attacks. The remaining five, known by some as “forever prisoners,” are indefinitely detained without charge.

Fundamentally flawed military commissions at Guantanamo Bay have not just violated the rights of the detainees, but they have deprived victims and their families of justice. As Human Rights Watch pointed out as far back as 2004: “bringing people to justice requires fair trials.” But fair trials are far from the reality at Guantanamo due to extensive delays stemming from due process violations, torture of defendants, and other issues.

Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, the alleged mastermind of the Sept. 11 attacks, is perhaps the highest-profile case. More than 20 years after the attacks, his case remains in the pretrial phase while thousands of surviving victims and loved ones await legal reckoning. During these two decades, U.S. federal courts have prosecuted nearly 1,000 cases involving alleged domestic and international terrorism.

It is not too late for President Biden to make good on his commitment to end detention at Guantanamo Bay. The administration should immediately proceed with transfers of detainees who have been cleared to go to third countries. They should prosecute the rest in fair proceedings before federal courts and end the detention of people not charged with a crime.

As long as the Guantanamo Bay detention facility remains open, the United States will continue to pay the price.

Leah Hebron, an Orlando native, is an associate in the Washington office of Human Rights Watch on U.S. foreign policy and national security issues.