(New York) – The Thai government’s decision to delay enforcement of key provisions of the new torture and enforced disappearance law should be immediately reversed, Human Rights Watch said today.

On February 14, 2023, the Thai government approved a decree to postpone enforcement of articles 22 to 25 of the Act on Prevention and Suppression of Torture and Enforced Disappearance from February 22 to October 1. The government claimed more time was needed to ready officials nationwide and procure equipment – such as cameras and voice recorders – required by the law to prevent abuses during arrest and interrogation.

“The Thai government keeps finding new reasons not to tackle the serious problems of torture and enforced disappearance in the country,” said Elaine Pearson, Asia director at Human Rights Watch. “All along the police and other security officials knew training and equipment would be needed to enforce the new law, but instead they could only come up with excuses.”

The relevant articles essentially stipulate measures to prevent practices that facilitate torture and enforced disappearance by requiring officials to continuously record audio and video throughout the arrest and detention process. Officials are required to report reasons for the arrest and detention, as well as the identity, whereabouts, and physical conditions of detainees. Thai courts are authorized to issue an order requiring officials to disclose information about detainees to their relatives or any other persons acting in their interest.

The Thai government’s decision will make it extraordinarily difficult to enforce the Act on Prevention and Suppression of Torture and Enforced Disappearance because officials are not yet required to provide information about detainees or record arrests and interrogations to prevent abuses from taking place.

These barriers will allow abusive officials to continue to engage in practices that facilitate enforced disappearances, such as the use of secret detention by anti-narcotics units, as well as the secret military detention of national security suspects and suspected insurgents in the southern border provinces.

International law defines enforced disappearance as the detention of a person by state officials or their agents and a refusal to acknowledge the detention or to reveal the person’s fate or whereabouts. Disappearances are especially painful for the victims’ families.

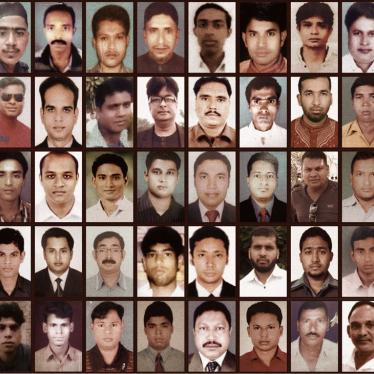

The United Nations Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances has recorded 76 cases of enforced disappearance in Thailand since 1980, including of the prominent Muslim lawyer Somchai Neelapaijit in March 2004. Human Rights Watch believes the actual number is higher as some families of victims and witnesses remain silent, fearing reprisals by the authorities if they speak out.

None of the disappearance cases have been resolved, and no one has been prosecuted. A key reason is that until passage of the Act on Prevention and Suppression of Torture and Enforced Disappearance, Thailand’s criminal code did not recognize enforced disappearance as a criminal offense. In 2012, Thailand signed but has yet to ratify the Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance. Thailand became party to the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment in 2007.

Torture and other ill-treatment in police custody have long been a problem in Thailand but successive governments have taken few steps to address it, Human Rights Watch said. After the dispersal of pro-democracy protests in Bangkok in October 2021, demonstrators were reportedly tortured in police custody. In August 2021, a group of police officers tortured a drug suspect to death in the Nakhon Sawan provincial police station. Human Rights Watch has also documented numerous cases related to counterinsurgency operations in Thailand’s southern border provinces in which police and military personnel tortured ethnic Malay Muslims.

“The UN and friendly governments should urge the Thai government to scrap the delay in the law and fully comply with its international legal obligation to make torture and enforced disappearance a criminal offense,” Pearson said. “For families waiting for answers for years about their missing loved ones, and those permanently scarred by their experiences of torture, every day with the law on hold is one day too many.”