(Port of Spain, Trinidad) – Over 90 nationals of Trinidad and Tobago, including at least 56 children, are unlawfully detained in life-threatening conditions as Islamic State (ISIS) suspects and family members in northeast Syria, Human Rights Watch said today. The government of Trinidad and Tobago has taken almost no action to help them return, even as countries including the United States and Barbados repatriate their own nationals.

Conditions in the camps and prisons holding Trinidadians and other ISIS-linked suspects and family members are increasingly dire. Turkish airstrikes in November 2022 hit a security post at one camp, killing eight guards, and came perilously close to striking one of the prisons. Health care, clean water, shelter, and education and recreation for children are grossly inadequate. Mothers interviewed by Human Rights Watch said they hide their children in their tents to protect them from sexual predators, abusive camp guards, and ISIS recruiters and fighters. Children have drowned in sewage pits, died in tent fires, and been hit and killed by water trucks, and hundreds have died from treatable illnesses.

“Trinidad and Tobago is turning its back on its nationals unlawfully held in horrific conditions in northeast Syria,” said Letta Tayler, associate crisis and conflict director at Human Rights Watch. “The government should bring home its citizens, help those who are victims of ISIS rebuild their lives, and fairly prosecute any adults linked to serious crimes.”

Human Rights Watch interviewed six Trinidadians held in the camps and prisons in 2022 and 2019, and seven family members, an attorney, and three advocates representing the detainees from December to February 2023. In addition, Human Rights Watch reviewed court documents related to cases filed by the families seeking to compel the government to bring home their loved ones. The names of those detained are withheld to protect their privacy.

Approximately 90 to 100 Trinidad and Tobago nationals are detained in northeast Syria by US-backed, Kurdish-led regional forces, according to family members and advocates. They include an estimated 21 women, at least one of them a grandmother, and at least 56 children in Roj and al-Hol, two locked camps for families with alleged ISIS links. Forty-four of the children in the camps are age 12 or younger and 15 are under age 6, family members said. At least 33 children were born in Syria including one child, born in al-Hol, who is only 3. In addition, at least 13 Trinidadian males, including at least one teenage boy, are held in other detention centers. At least six of the older boys and men – the teenager, 17, and five men ages 18 to 20 – were taken to Syria by family members when they were children.

All six Trinidadians whom Human Rights Watch interviewed in locked camps and other detention centers in northeast Syria said that more than anything, they wanted to go home.

“My father lied to me – he told me that we were going to Disneyland,” said a detained 17-year-old Trinidadian boy taken by his father to Syria in 2014. “It’s not my fault, it’s my father’s fault. I wish I never came here in Syria. I just want to come back home, you know.”

A 19-year-old Trinidadian youth said: “My dad told me I was going to go to a hotel in Egypt and swim in a pool. I was 11 years old. I only knew the names of countries like Trinidad and America.” He was among about 30 foreign youths – older teens and young men – detained 23 hours a day in a cell in Alaya prison that was just big enough to fit all their mattresses on the floor. The youths had only one toilet and shower and the stench permeated the cell, he said.

Three Trinidadians who came to Syria as adults said they wrongly thought they were going to a Muslim utopia, only to learn once they arrived that ISIS would not let them leave.

“This is a nightmare I cannot wake up from,” said a detained Trinidadian woman, adding that she was willing to serve prison time in Trinidad if she and her family were allowed home. “As Muslims we wanted to experience the Islamic State like Christians want to visit Jerusalem,” said the woman, one of nine members of the same family detained in northeast Syria. “It was so easy to get to Syria…. But then we found there was no way out.”

Most of the Trinidadians were rounded up in late 2018 or early 2019 by the US-backed Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) as they toppled the last remnant of ISIS’s self-declared “caliphate” in northeast Syria. They are among nearly 42,000 other foreigners from about 60 countries and more than 23,000 Syrians held as ISIS suspects and family members in northeast Syria.

In addition, four women from Trinidad and Tobago are imprisoned in Iraq with their seven children, family members said. The women were convicted of ISIS links in neighboring Iraq, where Human Rights Watch has found serious, widespread flaws in prosecutions of terrorism suspects, including of foreign women.

None of the detained foreigners has been able to challenge the necessity and legality of their detention, making their detention arbitrary and unlawful. Their detention conditions are cruel and degrading, and in many cases inhuman, and may amount to torture. Governments that knowingly and significantly contribute to the detainees’ abusive confinement may be complicit in their unlawful detention.

At least 36 countries have repatriated some or many of their nationals from northeast Syria. Repatriations have increased since October 2022 with at least 10 countries, including Barbados, bringing back some or many of their nationals. Many repatriated children are successfully reintegrating in their home countries, Human Rights Watch research has found.

Yet authorities in Trinidad and Tobago have not taken steps to bring home their nationals detained in northeast Syria for investigation and, if warranted, prosecution, citing security concerns. It is only known to have allowed the returns of eight nationals – a woman with two children, another woman and two teenage girls, and two young boys – and none since 2019. Most made it out of Syria without the government’s help.

Human Rights Watch wrote to the minister of national security on December 21, 2022, requesting details on Trinidad and Tobago’s policies and practices regarding the repatriation of its nationals from northeast Syria, but despite repeated requests, had not received the requested information as of February 15, 2023. On February 15, 2023, Attorney General Reginald Armour wrote to Human Rights Watch that his office “has been working assiduously with all stakeholders,” including other government ministries, on a policy framework for repatriations, but gave no timeline. A separate February 15, 2023 communication from the Ministry of Foreign and CARICOM affairs also indicated that it was “actively engaged” on the issue.

The government of Trinidad and Tobago should urgently ensure that all its nationals detained in northeast Syria and Iraq can come home, giving priority to children and their mothers, and to particularly vulnerable detainees. The government should also provide individualized rehabilitation and reintegration support for returnees, ensuring that the best interests of the child guide all decisions regarding returned children. Once home, adults implicated in serious ISIS-related crimes can be prosecuted in line with international due process standards. Donors, United Nations entities, and other countries with close ties to Trinidad and Tobago should support this process.

“Most of the Trinidadians detained in northeast Syria are children who never chose to live under ISIS,” said Jo Becker, children’s rights advocacy director at Human Rights Watch. “These children should have the chance to go home, go to school, and enjoy their childhood instead of suffering because of their parents’ decisions.”

For detailed findings, please see below.

Methodology

Human Rights Watch has interviewed more than 100 detainees, including the six Trinidadians in trips to northeast Syria and remotely since 2019, as well as dozens of administrators and staff in detention facilities; aid workers; regional, foreign, UN, and European Union officials; and relatives and lawyers in detainees’ countries of nationality.

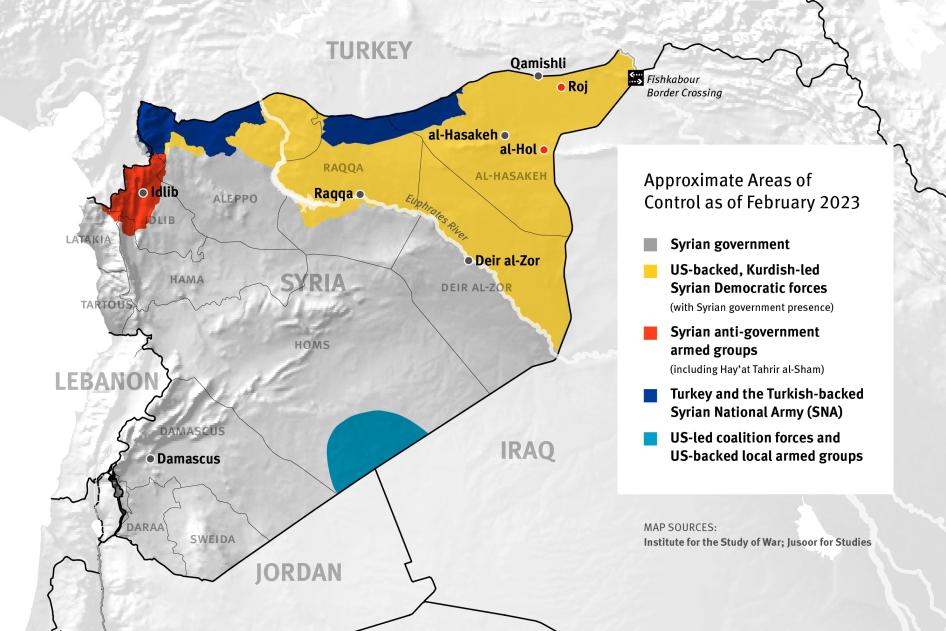

Map

At least 130 nationals of Trinidad and Tobago, an archipelagic nation of about 1.5 million people, traveled to ISIS-controlled territory between 2013 and 2016, according to Trinidad and Tobago’s Ministry of National Security. That is more people per capita than from any other Western country. Most came from three tight-knit communities in Trinidad and went to Syria and Iraq as families, taking their children. Some Trinidadian women also gave birth to children in Syria, and at least one Trinidadian infant died from illness. At least 30 Trinidadian men were killed in northeast Syria, based on interviews with family members and published reports.

Inadequate Food, Water, Health Care, Shelter

Detainees and family members said that the Trinidadian women and children living in tents inside the locked camps lack adequate food, clean water, and health care. A Trinidadian woman with three children told a family member through recorded voice messages that her tent was torn and regularly flooded. Another Trinidadian woman with five children told a family member in December that at times, they received very little food and that her children were frequently sick.

Several Trinidadian women have injuries untreated since 2019, and some of the children have come down with acute or recurrent diarrhea, fevers, and other illnesses without receiving appropriate medication or care, family members said. The Trinidadian woman who is one of nine family members held in northeast Syria said her detained mother, who is in her late 50s, cannot walk. A member of another family said their daughter had lost the use of her arm in a 2019 bomb attack in Syria.

In the prisons and other detention centers holding Trinidadian men and at least one Trinidadian boy, health care, counseling, and other essentials are even scarcer than in the locked camps for women and their children. Hundreds of detainees in at least one prison holding foreign detainees have tuberculosis, severe skin infections, and festering wounds, sources including aid workers said.

At Alaya, the prison for men, the 19-year-old Trinidadian was among about 30 foreign teenage boys and young men held in a separate youth “rehabilitation” cell barely large enough for them to sleep on mattresses on the floor. He said the youths were allowed only one hour a day outdoors, in a courtyard that was too small for them all to play sports at once. For the most part, fresh produce consisted of the occasional “tiny” orange or apple, he said.

Conditions are somewhat better for boys held in Houry, a locked, heavily guarded, so-called rehabilitation center with dormitories and a courtyard. The boys are allowed to play football and have access to keyboards and guitars at certain hours. But in visits in May 2022 and 2019, Human Rights Watch observed them mostly sitting with vacant stares or walking restlessly around the courtyard, and many said that they mostly had nothing to do.

Regional authorities have also held foreign women and children in women’s prisons for days, weeks, or months, often during camp transfers. The Trinidadian woman who is one of nine family members held in northeast Syria said guards placed her and four of her children in a prison for a month in 2021 while moving them from al-Hol to Roj, where the authorities have moved women and children they consider more moderate. Authorities initially refused to give her diapers for her youngest child, then 2 years old, saying the child was too old for them, she said.

Family members said that several Trinidadian women and children in the locked camps suffer from depression and post-traumatic stress disorder, and some have other mental health conditions, such as schizophrenia. One family member said that the Trinidadian children feel increasingly abandoned as they observe detainees from other countries leave to return to their countries. “The kids become depressed, and ask, ‘When is it our turn to go home?’” she said. She said that her eldest niece, now 16, may be suffering from depression and no longer sends voice messages or leaves the family’s tent.

All three Trinidadian youths detained separately from their families described being traumatized by the horrific events they had endured while their fathers or stepfathers forced them to live under ISIS. They spoke of close relatives being killed in fighting, and of living in constant fear of being executed by ISIS on the one hand or killed in US-led coalition airstrikes on the other.

One boy said that ISIS imprisoned and beat him eight times. In separate interviews, he and his stepbrother said that their 6-year-old sibling died when he shot himself in the head in the family’s home in ISIS-held territory in 2015 while playing with a loaded gun.

The Trinidadian youth in Alaya prison said in May that he needed medical care but that most of all, he was profoundly distraught:

I’m okay physically, but mentally, not at all. I don’t have no [any] connection with my family here. My mother, she is in Trinidad. There are no books. Before we used to make hearts and stuff like [necklaces from] beads but it’s the same activity, over and over. My bones, they break easily. I don’t know why. About two months ago I fell and my hand broke. The prison doctor gave me painkillers. My hand healed but in the wrong place. I used to wear glasses. My glasses broke and they never brought me replacements.

Violence and Death

Violence in the camps is common. At least 42 people, including children, were killed during 2022 in al-Hol, the larger camp, several of them by ISIS loyalists. Hundreds more have died from untreated illness or malnutrition.

One Trinidadian whose daughter-in-law and three grandchildren are detained in Roj camp said, “It’s really scary for a woman trying to keep her children away from the violence. It’s a desperate situation.” Another Trinidadian said his daughter-in-law was afraid for her 10-year-old daughter, citing sexual assaults in the camps. In November, two Egyptian sisters, both under 15, were found dead in an al-Hol sewage canal after being raped and stabbed.

More than 500 people, including an unknown number of detained men and boys, died during a prison battle between ISIS and the US-backed Syrian Democratic Forces in January 2022.

Some young Trinidadian children in the locked camps attend informal kindergartens once or twice a week, but most of the children have little or no access to education. One family member said her daughter-in-law was a primary school teacher before traveling to Syria and is teaching her two children herself. Other children who were of school age when first detained have missed out on nearly four years of education. The grandfather of three Trinidadian children, ages 5 to 10, said, “The children are just languishing there, with no school.”

Education is scarce or nonexistent in detention centers holding foreign boys and men as well. The 17-year-old Trinidadian boy held in the Houry Center said he wants to become a doctor or teacher but can barely read and write English, the official language of his home country. He said he has received almost no education since his father took him with four siblings and a stepbrother to live under ISIS in 2014, when he was about 7. When Human Rights Watch visited the Houry Center in 2022, students said they had some classes in math and Arabic, but the library shelves were almost bare.

In the cell for foreign boys and young in men in Alaya, the 19-year-old Trinidadian said he and the other youths had no books at all. A humanitarian aid group began some classes for the youths at Alaya in May 2022, but they are basic, an aid worker with knowledge of the program said.

According to family members, at least six Trinidadian youths – an adolescent boy and five young men whom regional authorities initially detained as children – are held in all-male prisons and other detention centers where they rarely see their family members detained in the region, if at all. At least three of these Trinidadian boys were forcibly separated from their mothers at gunpoint by the regional Syrian Democratic Forces during the fall of ISIS.

The Trinidadian woman who is among nine members of the same family held in northeast Syria said her two sons, then 14 and 15 years old, were taken with their father by regional security forces when the family fled an embattled, ISIS-held area in January 2019.

“I haven’t seen my sons in nearly four years,” said the woman, who is detained just a few hours’ drive away, in May. “Do you know what that does to a mother? Nothing you eat tastes the same without them.” For months, the woman said, the authorities would not tell her where her sons were. Two years passed before regional security agents, called Asayish, gave her a photo of them. Since her sons were taken, she said, she has only received three letters. “They said they are okay,” she said. “But how do I know?”

The woman said she had taken out loans from other women held in Roj to send money for clothes and shoes for her sons, while also taking cleaning and cooking jobs in the camp to support her four daughters and her infirmed mother. “I am literally begging [for work and money] like a dog,” she said.

Another Trinidadian teen, now 19, said his mother cloaked him in an abaya when they left ISIS-held territory in 2019. But the security forces discovered the disguise and separated him from his mother, he said from the Houry Center in 2019.

Three other detained Trinidadian boys or young men held separately from family members are the children or stepchildren of fathers who according to family members died in Syria. They include the 17-year-old boy held in the Houry Center, who in May said he had only spoken twice to his mother in Trinidad in the preceding two years.

When boys approach or reach adolescence in the locked camps, they, too, are commonly taken at gunpoint by security forces and placed in Houry and other detention centers without their mothers and siblings, family members and aid workers told Human Rights Watch. In many cases, guards take the children without informing the mother or letting her know the child’s whereabouts for weeks or months, if at all, they said.

A Trinidadian family member said her sister, detained in Roj camp, was gravely concerned that guards would take her son from her. “Trinidadian women are coming and telling my sister they [local security forces] will take him. Usually when boys are taken, the mothers don’t know where they are.”

Government Inaction

Top UN officials, US military officials, and security experts have repeatedly called for the repatriation of foreign ISIS suspects and their family members from northeast Syria as soon as possible. They say that leaving them in the locked camps and prisons carries greater risks – including escape and vulnerability to ISIS recruitment – than bringing them home. The Kurdish-led regional authority, called the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria, has also called for their repatriation and for international aid to improve detention conditions, saying that detaining them is a “burden.”

Family members of the detained Trinidadians have repeatedly implored their government to help them bring home their loved ones detained in northeast Syria as well.

In 2018, Trinidad and Tobago’s national security minister established a Repatriation and Reintegration Committee (also called “The Nightingale Committee”) to develop a policy, legislative framework, and operational plans for the repatriation and reintegration of people returning to Trinidad and Tobago from conflict areas. An official from the National Security Ministry stated in a 2020 court affidavit that a policy and draft legislation were “at an advanced stage.” Media also reported in January 2023 that the government was drafting a “Returnee Bill.” However, neither the draft legislation nor a draft policy has been made public.

In his February 15, 2023 letter to Human Rights Watch, Attorney General Reginald Armour stated the government has been working on a “holistic” policy framework:

[T]he office of the Attorney General … has been working assiduously with all stakeholders, including the Ministry of National Security in tandem with other Ministries of government to build out a draft policy framework to address the complex issues of persons requiring specialist attention and care, to safely reintegrat[e] them into society having returned from geographical areas marred by war and extreme violence whilst safeguarding national security interests, the balancing of rights and the taking of all requisite steps to ensure that persons constitutional rights are preserved and respected.

In a separate letter to Human Rights Watch, an official for the Ministry of Foreign and CARICOM Affairs stated that the government was “actively engaged in the consideration of the repatriation and reintegration” of its citizens from war zones in Syria and Iraq.

Trinidadian authorities have cited various reasons for not repatriating thus far, including challenges in verifying the identification and nationality of those requesting repatriation, ascertaining whether those requesting repatriation, including children, have engaged in violence, including with ISIS, and determining whether children born in Syria are in fact the children of Trinidad and Tobago citizens.

However, other countries have worked with aid groups and local authorities in northeast Syria to verify identities of nationals through DNA samples. Domestic intelligence agents and the judiciary can investigate, monitor, and prosecute their nationals if appropriate once they are home, Human Rights Watch said.

The authorities also stated in September 2020 that those seeking return had not applied for exemptions to Trinidad and Tobago’s Covid-19 border restrictions. But lacking consular assistance, detainees would have had no way to apply in advance for such exemptions. The government could have quarantined them upon arrival. And the government lifted the Covid-19 restrictions in July 2022.

Family members of Trinidad and Tobago nationals have filed at least three court cases to compel assistance from the government, including emergency travel documents and a formal agreement allowing their return. A high court judge ruled in April 2021 that repatriation-related matters fell within the purview of the government, not the courts. The court also found that the state was under no duty to engage in “international intervention in support of a citizen.” By contrast, courts in Canada and Germany, as well as UN rights committees, have found that governments have obligations to take reasonable steps to help their nationals arbitrarily detained in Syria, though the Canada case is currently on appeal.

In January 2021, a group of UN independent experts sent official letters to the governments of Trinidad and Tobago and 56 other countries, urging them to repatriate their nationals without delay and expressing serious concerns at the deteriorating security and humanitarian conditions in al-Hol and Roj. As of February 15, 2023, 32 governments had replied to the letters, but not Trinidad and Tobago.

A Trinidadian with a daughter and several grandchildren in Roj camp said, “We are really disappointed in our government.… Trying to save these children should be a priority.” Another family member who first contacted the government in 2019 and provided officials with birth certificates and photos of her family members, said, “It’s just a runaround. It’s very frustrating.”

Repatriations by Other Countries

Since 2019, at least 36 countries have repatriated or allowed home more than 6,600 of their nationals, including more than 4,600 to neighboring Iraq, according to figures from the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria, the region’s governing body, as well as aid groups and other sources. Some countries, including Denmark, Finland, Germany, Kazakhstan, Kosovo, Russia, Sweden, Tajikistan, Ukraine, the US, and Uzbekistan, have now repatriated many or most of their nationals who are women and children. Few countries have brought back any men.

Since October 2022, at least 10 countries have brought some or additional nationals home: 17 to Australia, 3 to Barbados, 4 to Canada, 102 to France, 12 to Germany, 1,245 to neighboring Iraq, 40 to the Netherlands, 38 to Russia, 15 to Spain, and 2 to the UK.

Many repatriated children are successfully reintegrating in their home countries. Human Rights Watch research on approximately 100 children brought home to seven European or Central Asian countries found that most children are attending school, with some at the top of their class. Most enjoy a wide range of activities with their peers, including football, skating, cycling, dancing, crafts, and music, and appear to be adjusting well. Human Rights Watch found that some children exhibited emotional or behavioral issues related to trauma they experienced while living under ISIS or in the detention camps, or struggled to catch up in school, and benefited from learning assistance and psychosocial support.

The US, which leads the 85-member Global Coalition Against ISIS and has military bases in northeast Syria, has helped several countries extract their nationals for repatriation, including with airlifts. The US has close ties to Trinidad and Tobago and has publicly stated its willingness to assist other countries in repatriating their nationals. The US has brought home 39 of its nationals for rehabilitation, reintegration, and prosecution.

Domestic Tools to Prosecute ISIS Crimes

Trinidad and Tobago has supported accountability for the gravest crimes of concern to the international community and was one of the first countries to join the International Criminal Court, which investigates and prosecutes these crimes; namely, genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity, and the crime of aggression. Trinidad and Tobago’s International Criminal Court Act of 2006 empowers domestic courts to prosecute genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity, including in many cases when they are committed abroad.

The country’s Anti-Terrorism Act of 2005 gives domestic courts jurisdiction over terrorism-related offenses, including those committed abroad.

Under international law, everyone has the rights to life; to a nationality and to enter one’s country; to be free from torture and other ill-treatment, including in detention; to fair trials; and to freedom from arbitrary deprivation of liberty. Governments have obligations to take all reasonable measures to protect the rights of their nationals, including abroad when they face life-threatening risks or torture. In all actions concerning children, the best interests of the child should be a primary consideration.

Enforced disappearances, which include the refusal by authorities to provide information on what became of a person they detained or where they were being held, are also strictly prohibited. If part of a widespread or systematic attack against civilian population, enforced disappearances are crimes against humanity. Detention based solely on family ties is a form of collective punishment, which during an armed conflict is a war crime.

The UN Human Rights Committee has repeatedly found that arbitrary, as well as indefinite or protracted detention, combined with dire conditions and a failure to provide procedural rights to detainees, constitutes torture or other cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment, by “cumulatively inflicting serious, irreversible psychological harm.”

Binding UN Security Council resolutions, including Resolution 2396 of 2017, call on all UN member states to prosecute those who have committed ISIS-related crimes, an impossibility at present in northeast Syria, which has no local courts for foreign ISIS suspects. These resolutions emphasize the importance of assisting women and children associated with groups like ISIS who may themselves be victims of terrorism, including through rehabilitation and reintegration.

In separate rulings in February and October 2022, the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child found that France and Finland violated the rights to life and to freedom from inhuman treatment of children they had not repatriated from northeast Syria.

In September 2022, the European Court of Human Rights found that France violated the rights of women and children seeking repatriation by failing to adequately and fairly examine their requests for repatriation. In January 2023, the Committee Against Torture found that France had violated the Convention Against Torture by refusing to repatriate women and children from northeast Syria. Even if the French State “is not at the origin of the violations suffered” by the women and children in the camps, “it remains under an obligation” to protect them against serious human rights violations “by taking all necessary and possible measures,” the committee said.

Similarly, in a joint 2020 legal opinion, two UN independent experts – the special rapporteur on the promotion and protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms while countering terrorism and the special rapporteur on extra-judicial, summary or arbitrary executions – found that in the cases of foreign ISIS suspects and family members arbitrarily detained in northeast Syria, “[s]tates have a positive obligation to take necessary and reasonable steps to intervene in favor of their nationals abroad, should there be reasonable grounds to believe that they face treatment in flagrant violation of international human rights law.”

The special rapporteur on countering terrorism has also repeatedly stated that the urgent return and repatriation of suspected foreign fighters and their families from conflict zones is “the only international law-compliant response” to their arbitrary, indefinite detention.