Walid Khalili’s nightmare began on the morning of November 10, 2023. The 36-year-old father of three, a Palestinian Medical Relief Society paramedic and ambulance driver, had been dispatched to the Tel al-Hawa neighborhood of Gaza City to rescue four wounded men. When his ambulance reached the Barcelona Garden, twenty meters from the Labor Ministry building, on Mughrabi Street, he saw four men surrounded by Israeli forces.

“I saw the four men being executed in cold blood,” Khalili said. “I saw it with my own eyes, I was three meters away. When they were shot, I hid under the ambulance, and next to it there was a building, so then I ran inside the building. The Israeli forces raided the building and started yelling at me to raise my hands.” Soldiers kicked and beat him with their rifle butts, breaking his ribs.

Human Rights Watch could not independently verify Khalili’s account of the killings. But his subsequent ordeal – including deportation from Gaza to detention facilities in Israel, torture, and denial of medical care – are consistent with the abuses in Israeli detention described by seven other healthcare workers we interviewed. His account is also consistent with reports by other rights groups, the United Nations human rights office, and journalists.

The soldiers forced Khalili to strip naked in public, zip-tied his hands behind his back, blindfolded him, took him to another location. “They kept telling me, ‘Say you’re Hamas,’” he said. He recalled the bitter November cold. Soldiers then placed him in an open-back military vehicle, hit him, and drove him to an open area, where he was forced to lie face-down on sandy ground. Soldiers repeatedly shoved his face into the sand with their boots and threatened to kill him, Khalili said.

One soldier pushed the muzzle of an assault rifle to his head, another doused him with gasoline, threatening to set him on fire, and others drove a military vehicle quickly toward him as if to run him over – a tactic that another former detainee separately described to us – apparently to terrify him into confessing to being a member of Hamas.

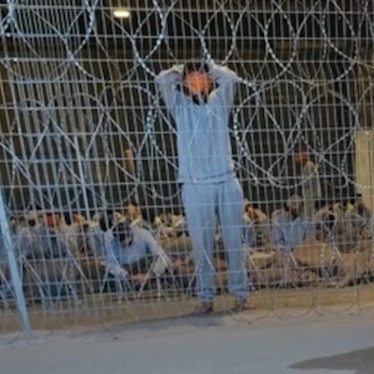

Israeli soldiers then transferred Khalili to Sde Teiman military base in southern Israel, northwest of the city of Beer Sheva, about 30 kilometers from Gaza. He said that at the detention facility, Israeli soldiers dragged him on the ground, removed the cuffs on his ankles, dressed him in adult diapers, and removed his blindfold. He saw he was in a large building “like a warehouse,” with chains hanging from the ceiling. Dozens of detainees, also in diapers, were suspended from the ceiling, with the chains attached to their square metal handcuffs.

He said that personnel at the facility then suspended him from a chain, so his feet were not touching the ground, dressed him in a garment and a headband that were attached to wires, and shocked him with electricity. He said:

The world was spinning around, and I fainted. They hit me with batons. I kept fainting and hallucinating. He kept asking me about the hostages, and moving Hamas hostages, and where I was on October 7. With every question I was electro-shocked to wake me up. He told me confess and we will stop torturing you.

Khalili said he was given electric shocks every second day in addition to being suspended in stress positions and having cold water thrown on him.

Khalili said that at three-day intervals, he was taken from the “warehouse” for interrogation. Before each interrogation, a soldier administered an unknown drug to him in pill form. “The pill made me feel weird, it was the first time I have felt like this, as if my inner mind was speaking what was in my heart, not me. I felt like I’m flying. I saw hallucinations.” An Israeli official whom Khalili said spoke fluent, unaccented Arabic interrogated him, focusing on the hostages taken to Gaza. The official “told me how many children I have, all their names, my address,” Khalili said, and threatened they would be killed if he did not confess.

Despite his broken ribs, Khalili said he received no medical treatment at Sde Teiman. Another detainee “had his leg amputated,” apparently as a result of prolonged shackling and exposure to cold. He said he saw a detainee in the “warehouse” experience what he believes was cardiac arrest; a soldier brought in an Israeli medical worker who confirmed the detainee was dead. Israeli forces brought the dead body of another detainee into the warehouse, Khalili said. Prayer was prohibited.

After 20 days, Israeli forces transferred Khalili, alone, in a wheelchair and unable to stand, from Sde Teiman to a detention facility he called “al-Naqab” prison. He was cuffed and blindfolded, and said soldiers threatened him with rape while he was being transported. Upon arrival at al-Naqab, officials at the facility “took my fingerprints and gave me a number” to identify him. After a few days, he was given clothes. Another detainee, tasked to act as a translator and go-between by Israeli guards, was allowed to bring him food. He was questioned three more times but not physically tortured.

The other detainees at al-Naqab were also sick and wounded, and a man who was visibly “bleeding from his bottom” was brought in and placed next to Khalili. The man told Khalili that before he was placed in detention, “three soldiers took turns raping him with an M16 [assault rifle]. No one else knew, but he told me as a paramedic. He was terrified. His mental health was awful, he started talking to himself.”

Khalili was given over-the-counter anti-inflammatory painkillers and antibiotics but no other medical help at al-Naqab, he said. Bright lights were never turned off at the facility, making it difficult to sleep. Detainees slept on thin mats on the ground, without pillows, cuffed and blindfolded. Breakfast was a piece of bread with cheese, tuna and tomato for lunch, and a piece of bread with jam for dinner, he said.

After more than 30 days at al-Naqab, Khalili said, he signed release papers at the prosecutors’ office and was given back his Palestinian ID document, but not his phone or cash (the equivalent of US$1,250) taken from him during his arrest in Gaza. Four days later, in late December 2023, he was released without charge at the Kerem Shalom/Karam Abu Salem crossing bordering the Gaza Strip and Egypt. He had weighed 80 kilograms when arrested, and now weighed 60, he said.

Back in Gaza, the Red Crescent Society provided Khalili with medical care and transferred him to Abu Youssef al-Najjar hospital in Rafah. The World Health Organization arranged for permission for him to be transferred for care to Egypt in May, but Israeli forces closed the Rafah border crossing on May 7.

When we were last in touch with him, Khalili was sheltering in the Mawasi area near Khan Yunis, and still awaiting possible transfer to Egypt for medical care, separated from his family who are in northern Gaza. “I cry every day without my family,” he said. “I’m alone in the south, I have no one. I swear I don’t need anything but to be with my family.” He has not yet met his youngest son, who was born in Gaza while he was in detention.

He still loses consciousness and feels “something in my head like microwaves, a loud sound,” and his hands cramp up, Khalili said. He finds it hard to sleep due to the pain from his broken ribs. When he sleeps, he has nightmares.