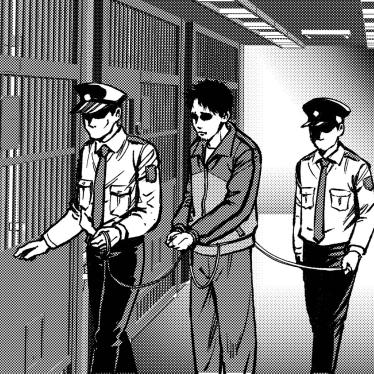

(Bangkok) – The 2024 acquittal on retrial of a decades-old death sentence shows that Japan’s criminal justice system remains in need of major reform, Human Rights Watch said today in its World Report 2025. Japan’s criminal justice system is marred by “hostage justice,” which typically involves prolonged pretrial detention coupled with interrogations without the presence of legal counsel, resulting in confessions obtained through manipulation and intimidation. Iwao Hakamata, 88, was arrested in 1966 and coerced to falsely confess to murdering a family of four.

For the 546-page world report, in its 35th edition, Human Rights Watch reviewed human rights practices in more than 100 countries. In much of the world, Executive Director Tirana Hassan writes in her introductory essay, governments cracked down and wrongfully arrested and imprisoned political opponents, activists, and journalists. Armed groups and government forces unlawfully killed civilians, drove many from their homes, and blocked access to humanitarian aid. In many of the more than 70 national elections in 2024, authoritarian leaders gained ground with their discriminatory rhetoric and policies.

“The exoneration of Iwao Hakamata after decades on death row because of a forced confession and a dysfunctional retrial system is a stark reminder that Japan needs to urgently reform its criminal justice system,” said Kanae Doi, Japan director at Human Rights Watch. “The Japanese government should end so-called hostage justice, and capital punishment.”

The following were other key developments in Japan during 2024:

- Japan’s asylum and refugee determination system remains strongly oriented against granting refugee status. In 2023, the Justice Ministry received 13,823 applications for refugee status, but recognized only 303 people as refugees. In June, the amended Immigration Control and Refugee Recognition Act, which lets Japan deport asylum seekers who apply for refugee status more than twice, went into effect.

- In February, in the wake of Human Rights Watch research, the Japanese government acknowledged that guards were violating a directive effectively banning penal institutions from using restraints on imprisoned pregnant women inside delivery rooms. In March, the Justice Ministry broadened the 2014 directive in line with international standards.

- In June, the Diet abolished the foreign technical intern training program and established a new training and employment system for foreign workers. While it will eventually allow migrant workers to change employers, critics say the conditions remain vague.

- In July, Japan’s Supreme Court ruled that the now-defunct Eugenic Protection Act was unconstitutional and ordered the government to compensate people sterilized under the law, most with genetic disorders About 25,000 people were sterilized between 1948 and 1996.

For decades, Japanese civil society groups have urged the establishment of an independent human rights institution, and various United Nations human rights mechanisms have echoed their calls. The Japanese government should address its weak systems for the protection of human rights by setting up a national human rights institution.