Summary

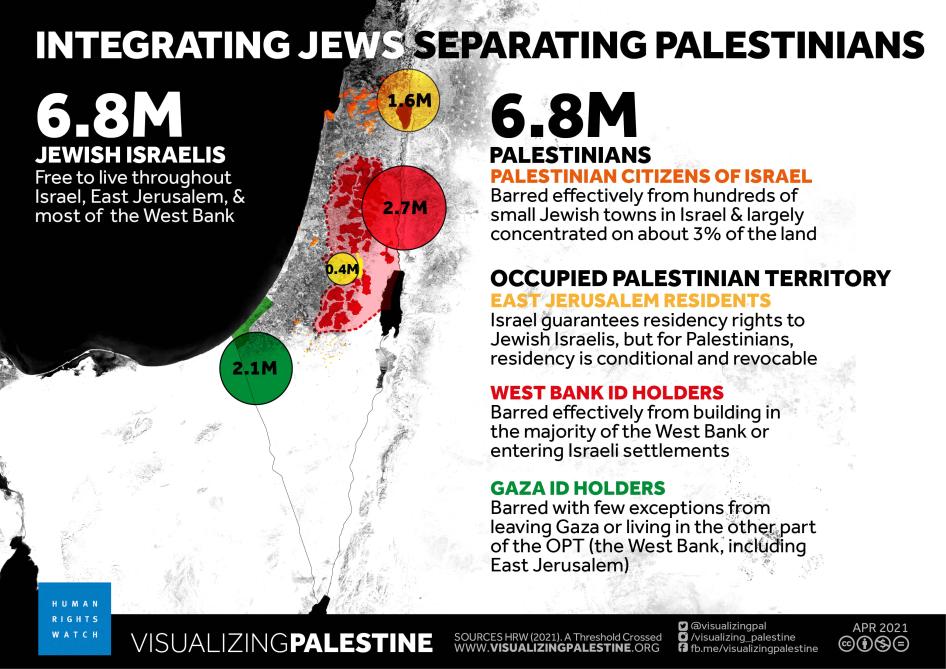

About 6.8 million Jewish Israelis and 6.8 million Palestinians live today between the Mediterranean Sea and Jordan River, an area encompassing Israel and the Occupied Palestinian Territory (OPT), the latter made up of the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and the Gaza Strip. Throughout most of this area, Israel is the sole governing power; in the remainder, it exercises primary authority alongside limited Palestinian self-rule. Across these areas and in most aspects of life, Israeli authorities methodically privilege Jewish Israelis and discriminate against Palestinians. Laws, policies, and statements by leading Israeli officials make plain that the objective of maintaining Jewish Israeli control over demographics, political power, and land has long guided government policy. In pursuit of this goal, authorities have dispossessed, confined, forcibly separated, and subjugated Palestinians by virtue of their identity to varying degrees of intensity. In certain areas, as described in this report, these deprivations are so severe that they amount to the crimes against humanity of apartheid and persecution.

Several widely held assumptions, including that the occupation is temporary, that the “peace process” will soon bring an end to Israeli abuses, that Palestinians have meaningful control over their lives in the West Bank and Gaza, and that Israel is an egalitarian democracy inside its borders, have obscured the reality of Israel’s entrenched discriminatory rule over Palestinians. Israel has maintained military rule over some portion of the Palestinian population for all but six months of its 73-year history. It did so over the vast majority of Palestinians inside Israel from 1948 and until 1966. From 1967 until the present, it has militarily ruled over Palestinians in the OPT, excluding East Jerusalem. By contrast, it has since its founding governed all Jewish Israelis, including settlers in the OPT since the beginning of the occupation in 1967, under its more rights-respecting civil law.

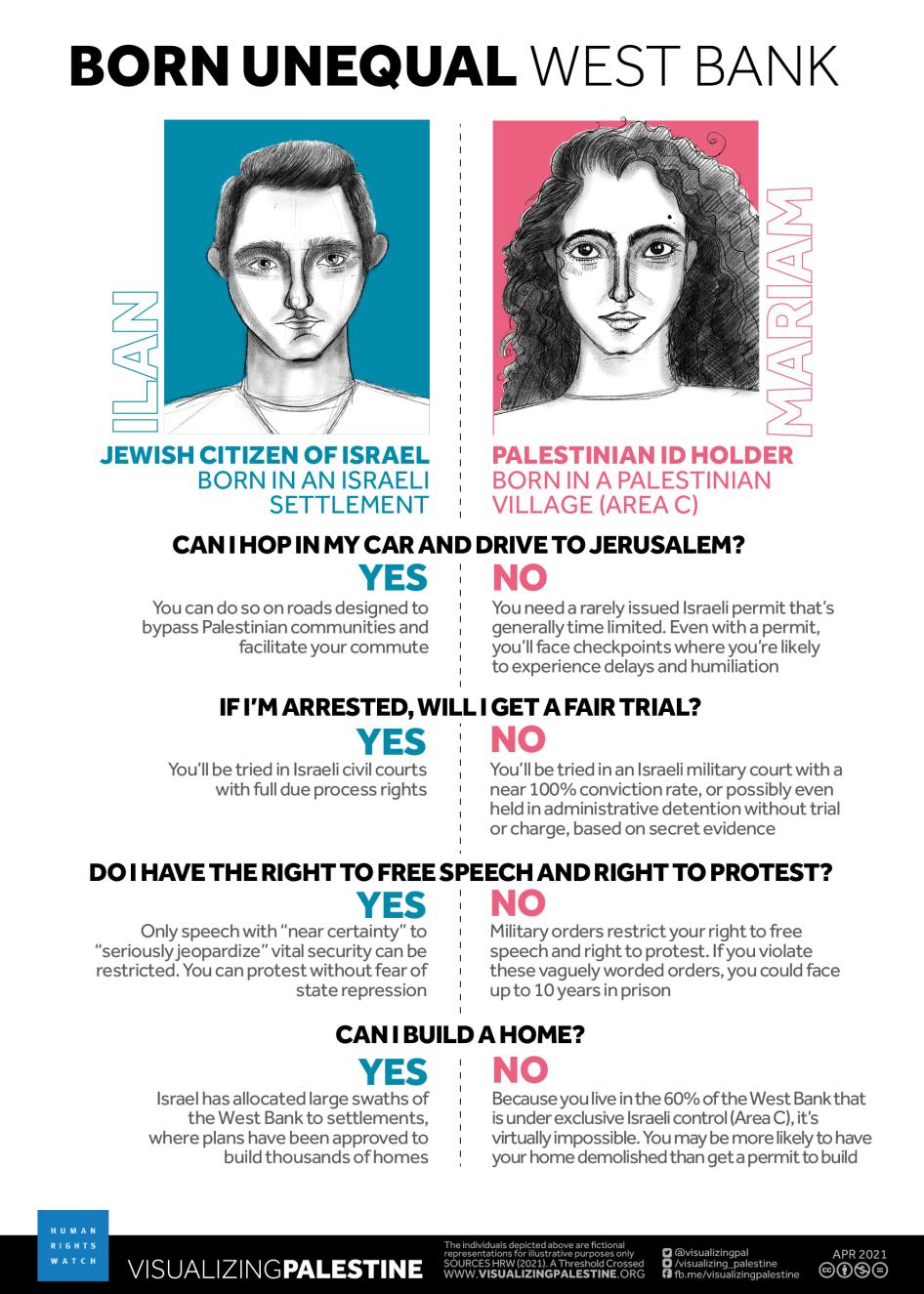

For the past 54 years, Israeli authorities have facilitated the transfer of Jewish Israelis to the OPT and granted them a superior status under the law as compared to Palestinians living in the same territory when it comes to civil rights, access to land, and freedom to move, build, and confer residency rights to close relatives. While Palestinians have a limited degree of self-rule in parts of the OPT, Israel retains primary control over borders, airspace, the movement of people and goods, security, and the registry of the entire population, which in turn dictates such matters as legal status and eligibility to receive identity cards.

A number of Israeli officials have stated clearly their intent to maintain this control in perpetuity and backed it up through their actions, including continued settlement expansion over the course of the decades-long “peace process.” Unilateral annexation of additional parts of the West Bank, which the government of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has vowed to carry out, would formalize the reality of systematic Israeli domination and oppression that has long prevailed without changing the reality that the entire West Bank is occupied territory under the international law of occupation, including East Jerusalem, which Israel unilaterally annexed in 1967.

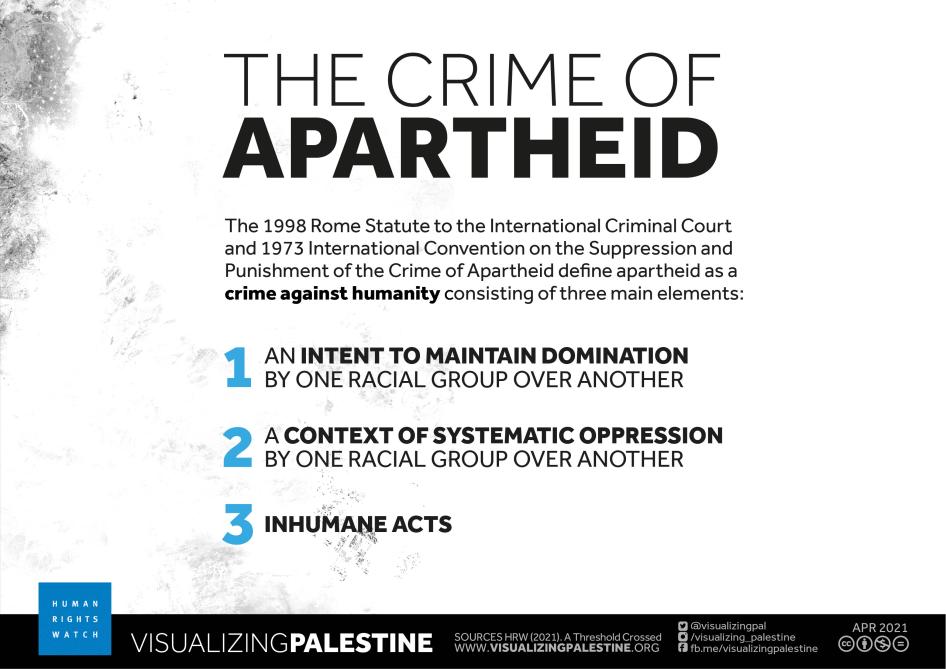

International criminal law has developed two crimes against humanity for situations of systematic discrimination and repression: apartheid and persecution. Crimes against humanity stand among the most odious crimes in international law.

The international community has over the years detached the term apartheid from its original South African context, developed a universal legal prohibition against its practice, and recognized it as a crime against humanity with definitions provided in the 1973 International Convention on the Suppression and Punishment of the Crime of Apartheid (“Apartheid Convention”) and the 1998 Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC).

The crime against humanity of persecution, also set out in the Rome Statute, the intentional and severe deprivation of fundamental rights on racial, ethnic, and other grounds, grew out of the post-World War II trials and constitutes one of the most serious international crimes, of the same gravity as apartheid.

The State of Palestine is a state party to both the Rome Statute and the Apartheid Convention. In February 2021, the ICC ruled that it has jurisdiction over serious international crimes committed in the entirety of the OPT, including East Jerusalem, which would include the crimes against humanity of apartheid or persecution committed in that territory. In March 2021, the ICC Office of Prosecutor announced the opening of a formal investigation into the situation in Palestine.

The term apartheid has increasingly been used in relation to Israel and the OPT, but usually in a descriptive or comparative, non-legal sense, and often to warn that the situation is heading in the wrong direction. In particular, Israeli, Palestinian, US, and European officials, prominent media commentators, and others have asserted that, if Israel’s policies and practices towards Palestinians continued along the same trajectory, the situation, at least in the West Bank, would become tantamount to apartheid.[1] Some have claimed that the current reality amounts to apartheid.[2] Few, however, have conducted a detailed legal analysis based on the international crimes of apartheid or persecution.[3]

In this report, Human Rights Watch examines the extent to which that threshold has already been crossed in certain of the areas where Israeli authorities exercise control.

Definitions of Apartheid and Persecution

The prohibition of institutionalized discrimination, especially on grounds of race or ethnicity, constitutes one of the fundamental elements of international law. Most states have agreed to treat the worst forms of such discrimination, that is, persecution and apartheid, as crimes against humanity, and have given the ICC the power to prosecute these crimes when national authorities are unable or unwilling to pursue them. Crimes against humanity consist of specific criminal acts committed as part of a widespread or systematic attack, or acts committed pursuant to a state or organizational policy, directed against a civilian population.

The Apartheid Convention defines the crime against humanity of apartheid as “inhuman acts committed for the purpose of establishing and maintaining domination by one racial group of persons over any other racial group of persons and systematically oppressing them.” The Rome Statute of the ICC adopts a similar definition: “inhumane acts… committed in the context of an institutionalized regime of systematic oppression and domination by one racial group over any other racial group or groups and committed with the intention of maintaining that regime.” The Rome Statute does not further define what constitutes an “institutionalized regime.”

The crime of apartheid under the Apartheid Convention and Rome Statute consists of three primary elements: an intent to maintain a system of domination by one racial group over another; systematic oppression by one racial group over another; and one or more inhumane acts, as defined, carried out on a widespread or systematic basis pursuant to those policies.

Among the inhumane acts identified in either the Convention or the Rome Statute are “forcible transfer,” “expropriation of landed property,” “creation of separate reserves and ghettos,” and denial of the “the right to leave and to return to their country, [and] the right to a nationality.”

The Rome Statute identifies the crime against humanity of persecution as “the intentional and severe deprivation of fundamental rights contrary to international law by reason of the identity of the group or collectivity,” including on racial, national, or ethnic grounds. Customary international law identifies the crime of persecution as consisting of two primary elements: (1) severe abuses of fundamental rights committed on a widespread or systematic basis, and (2) with discriminatory intent.

Few courts have heard cases involving the crime of persecution and none the crime of apartheid, resulting in a lack of case law around the meanings of key terms in their definitions. As described in the report, international criminal courts have over the last two decades evaluated group identity based on the context and construction by local actors, as opposed to earlier approaches focused on hereditary physical traits. In international human rights law, including the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD), race and racial discrimination have been broadly interpreted to include distinctions based on descent, and national or ethnic origin, among other categories.

Application to Israel’s Policies towards Palestinians

Two primary groups live today in Israel and the OPT: Jewish Israelis and Palestinians. One primary sovereign, the Israeli government, rules over them.

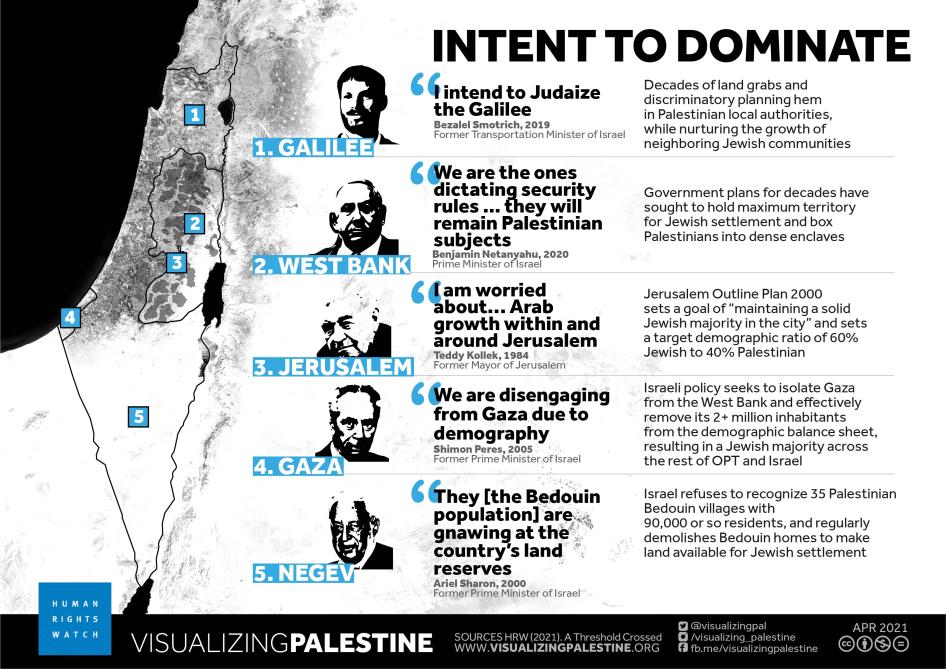

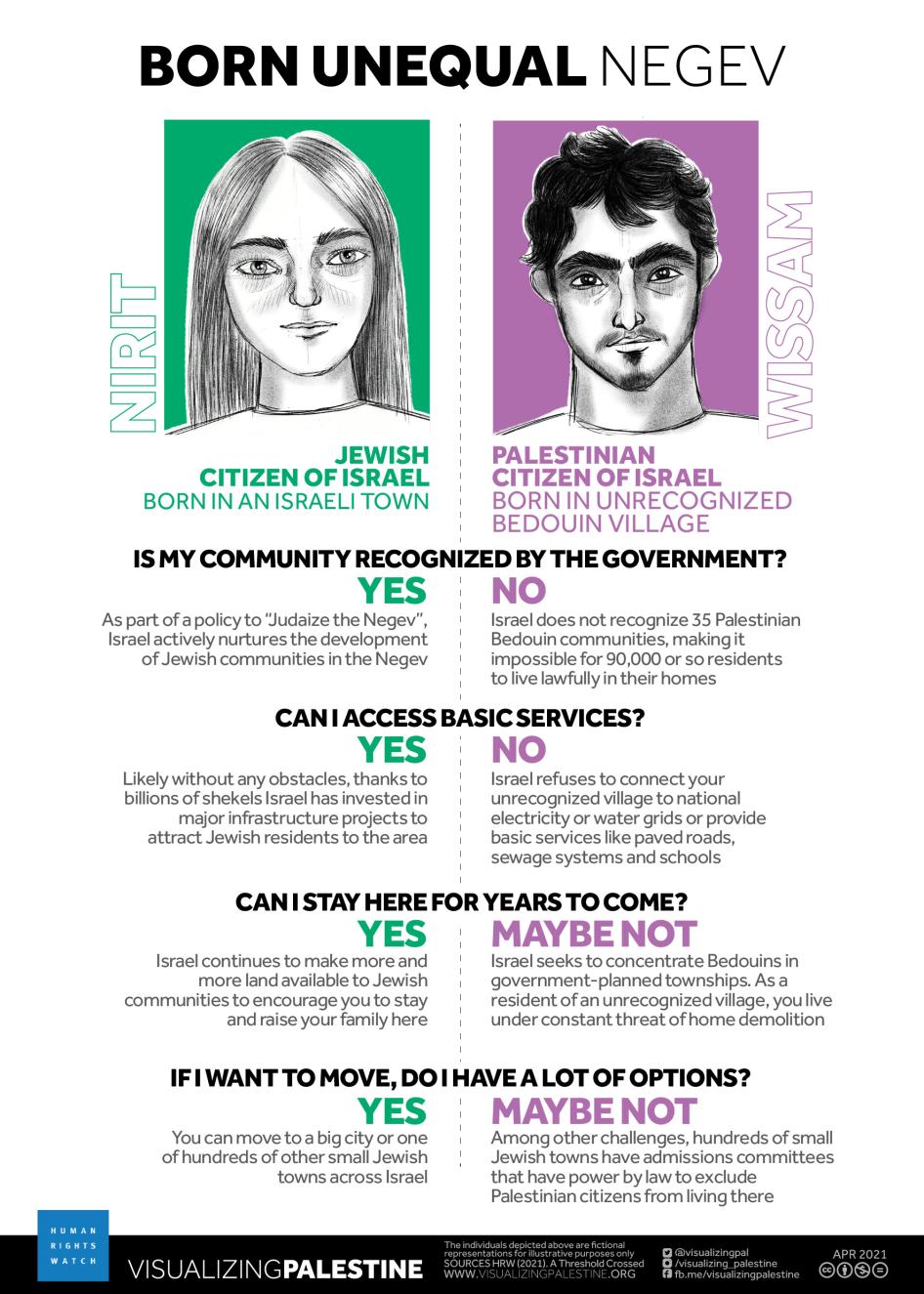

Intent to Maintain Domination

A stated aim of the Israeli government is to ensure that Jewish Israelis maintain domination across Israel and the OPT. The Knesset in 2018 passed a law with constitutional status affirming Israel as the “nation-state of the Jewish people,” declaring that within that territory, the right to self-determination “is unique to the Jewish people,” and establishing “Jewish settlement” as a national value. To sustain Jewish Israeli control, Israeli authorities have adopted policies aimed at mitigating what they have openly described as a demographic “threat” that Palestinians pose. Those policies include limiting the population and political power of Palestinians, granting the right to vote only to Palestinians who live within the borders of Israel as they existed from 1948 to June 1967, and limiting the ability of Palestinians to move to Israel from the OPT and from anywhere else to Israel or the OPT. Other steps are taken to ensure Jewish domination, including a state policy of “separation” of Palestinians between the West Bank and Gaza, which prevents the movement of people and goods within the OPT, and “Judaization” of areas with significant Palestinian populations, including Jerusalem as well as the Galilee and the Negev in Israel. This policy, which aims to maximize Jewish Israeli control over land, concentrates the majority of Palestinians who live outside Israel’s major, predominantly Jewish cities into dense, under-served enclaves and restricts their access to land and housing, while nurturing the growth of nearby Jewish communities.

Systematic Oppression and Institutional Discrimination

To implement the goal of domination, the Israeli government institutionally discriminates against Palestinians. The intensity of that discrimination varies according to different rules established by the Israeli government in Israel, on the one hand, and different parts of the OPT, on the other, where the most severe form takes place.

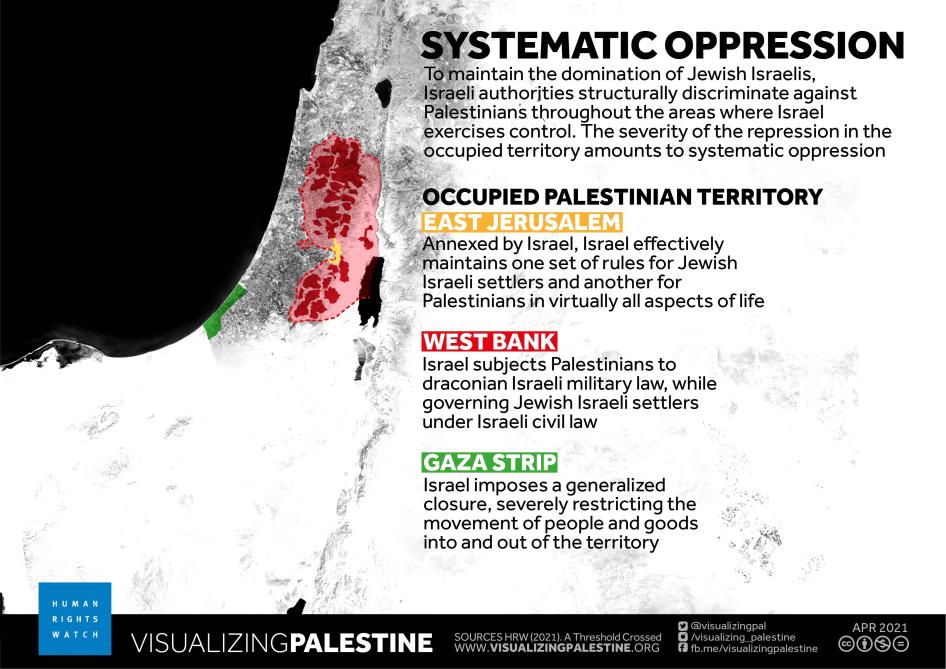

In the OPT, which Israel has recognized as a single territory encompassing the West Bank and Gaza, Israeli authorities treat Palestinians separately and unequally as compared to Jewish Israeli settlers. In the occupied West Bank, Israel subjects Palestinians to draconian military law and enforces segregation, largely prohibiting Palestinians from entering settlements. In the besieged Gaza Strip, Israel imposes a generalized closure, sharply restricting the movement of people and goods—policies that Gaza’s other neighbor, Egypt, often does little to alleviate. In annexed East Jerusalem, which Israel considers part of its sovereign territory but remains occupied territory under international law, Israel provides the vast majority of the hundreds of thousands of Palestinians living there with a legal status that weakens their residency rights by conditioning them on the individual’s connections to the city, among other factors. This level of discrimination amounts to systematic oppression.

In Israel, which the vast majority of nations consider being the area defined by its pre-1967 borders, the two tiered-citizenship structure and bifurcation of nationality and citizenship result in Palestinian citizens having a status inferior to Jewish citizens by law. While Palestinians in Israel, unlike those in the OPT, have the right to vote and stand for Israeli elections, these rights do not empower them to overcome the institutional discrimination they face from the same Israeli government, including widespread restrictions on accessing land confiscated from them, home demolitions, and effective prohibitions on family reunification.

The fragmentation of the Palestinian population, in part deliberately engineered through Israeli restrictions on movement and residency, furthers the goal of domination and helps obscure the reality of the same Israeli government repressing the same Palestinian population group, to varying degrees in different areas, for the benefit of the same Jewish Israeli dominant group.

Inhumane Acts and Other Abuses of Fundamental Rights

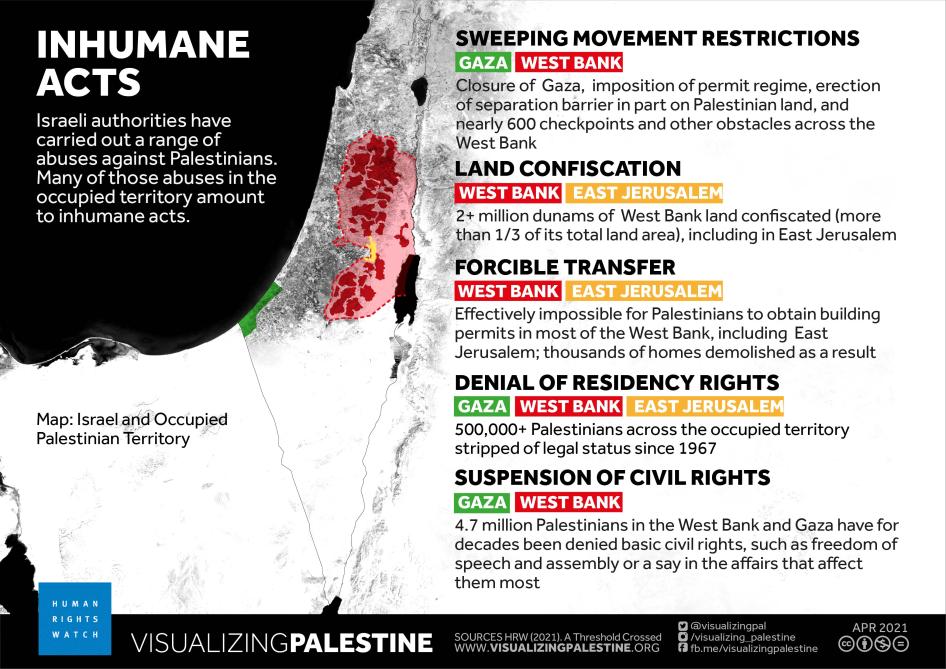

Pursuant to these policies, Israeli authorities have carried out a range of inhumane acts in the OPT. Those include sweeping restrictions on the movement of 4.7 million Palestinians there; the confiscation of much of their land; the imposition of harsh conditions, including categorical denial of building permits in large parts of the West Bank, which has led thousands of Palestinians to leave their homes under conditions that amount to forcible transfer; the denial of residency rights to hundreds of thousands of Palestinians and their relatives, largely for being abroad when the occupation began in 1967, or for long periods during the first few decades of the occupation, or as a result of the effective freeze on family reunification over the last two decades; and the suspension of basic civil rights, such as freedom of assembly and association, depriving Palestinians of the opportunity to have a voice in a wide range of affairs that most affect their daily lives and futures. Many of these abuses, including categorical denials of building permits, mass residency revocations or restrictions, and large-scale land confiscations, have no legitimate security justifications; others, such as the extent of restrictions on movement and civil rights, fail any reasonable balancing test between security concerns and the severity of the underlying rights abuse.

Since the founding of the state of Israel, the government also has systematically discriminated against and violated the rights of Palestinians inside the state’s pre-1967 borders, including by refusing to allow Palestinians access to the millions of dunams of land (1000 dunams equals 100 hectares, about 250 acres or 1 square kilometer) that were confiscated from them. In one region—the Negev—these policies make it virtually impossible for tens of thousands of Palestinians to live lawfully in the communities they have lived in for decades. In addition, Israeli authorities refuse to permit the more than 700,000 Palestinians who fled or were expelled in 1948, and their descendants, to return to Israel or the OPT, and impose blanket restrictions on legal residency, which block many Palestinian spouses and families from living together in Israel.

Report Findings

This report examines Israeli policies and practices towards Palestinians in the OPT and Israel and compares them to the treatment of Jewish Israelis living in the same territories. It is not an exhaustive evaluation of all types of international human rights and humanitarian law violations. Rather, it surveys consequential Israeli government practices and policies that violate the basic rights of Palestinians and whose purpose is to ensure the domination of Jewish Israelis, and assesses them against the definitions of the crimes against humanity of apartheid and persecution.

The report draws on years of research and documentation by Human Rights Watch and other rights organizations, including fieldwork conducted for this report. Human Rights Watch also reviewed Israeli laws, government planning documents, statements by officials, and land records. This evidentiary record was then analyzed under the legal standards for the crimes of apartheid and persecution. Human Rights Watch also wrote in July 2020 to Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, soliciting the government’s perspectives on the issues covered, but, as of publication, had not received a response.

The report does not set out to compare Israel with South Africa under apartheid or to determine whether Israel is an “apartheid state”—a concept that is not defined in international law. Rather, the report assesses whether specific acts and policies carried out by Israeli authorities today amount in particular areas to the crimes of apartheid and persecution as defined under international law.

Each of the report’s three main substantive chapters explores Israel’s rule over Palestinians: the dynamics of its rule and discrimination, looking in turn at Israel and the OPT, the particular rights abuses that it commits there, and some of the objectives that motivate these policies. It does so in terms of the primary elements of the crimes of apartheid and persecution, as outlined above. Human Rights Watch evaluates the dynamics of Israeli rule in each of these areas, keeping in mind the different legal frameworks that apply in the OPT and Israel, which are the two legally recognized territorial entities, each with a different status under international law. While noting significant factual differences among subregions in each of these two territories, the report does not make separate subregional determinations.

On the basis of its research, Human Rights Watch concludes that the Israeli government has demonstrated an intent to maintain the domination of Jewish Israelis over Palestinians across Israel and the OPT. In the OPT, including East Jerusalem, that intent has been coupled with systematic oppression of Palestinians and inhumane acts committed against them. When these three elements occur together, they amount to the crime of apartheid.

Israeli officials have also committed the crime against humanity of persecution. This finding is based on the discriminatory intent behind Israel’s treatment of Palestinians and the grave abuses carried out in the OPT that include the widespread confiscation of privately owned land, the effective prohibition on building or living in many areas, the mass denial of residency rights, and sweeping, decades-long restrictions on the freedom of movement and basic civil rights. Such policies and practices intentionally and severely deprive millions of Palestinians of key fundamental rights, including to residency, private property, and access to land, services, and resources, on a widespread and systematic basis by virtue of their identity as Palestinians.

Seeking Maximal Land with Minimal Palestinians

Israeli policy has sought to engineer and maximize the number of Jews, as well as the land available to them, in Israel and the portions of the OPT coveted by the Israeli government for Jewish settlement. At the same time, by restricting the residency rights of Palestinians, Israeli policy seeks to minimize the number of Palestinians and the land available to them in those areas. The level of repression is most severe in the OPT, although often less severe aspects of similar policies can be found within Israel.

In the West Bank, authorities have confiscated more than 2 million dunams of land from Palestinians, making up more than one-third of the West Bank, including tens of thousands of dunams that they acknowledge are privately owned by Palestinians. One common tactic they have used is to declare territory, including privately-owned Palestinian land, as “state land.” The Israeli group Peace Now estimates that the Israeli government has designated about 1.4 million dunams of land, or about a quarter of the West Bank, as state land. The group has also found that more than 30 percent of the land used for settlements is acknowledged by the Israeli government as having been privately owned by Palestinians. Of the more than 675,000 dunams of state land that Israeli authorities have allocated for use by third parties in the West Bank, they have earmarked more than 99 percent for use by Israeli civilians, according to government data. Land grabs for settlements and the infrastructure that primarily serves settlers effectively concentrate Palestinians in the West Bank, according to B’Tselem, into “165 non-contiguous ‘territorial islands.’”

Israeli authorities have also made it virtually impossible in practice for Palestinians in Area C, the roughly 60 percent of the West Bank that the Oslo Accords placed under full Israeli control, as well as those in East Jerusalem, to obtain building permits. In Area C, for example, authorities approved less than 1.5 percent of applications by Palestinians to build between 2016 and 2018—21 in total—a figure 100 times smaller than the number of demolition orders it issued in the same period, according to official data. Israeli authorities have razed thousands of Palestinian properties in these areas for lacking a permit, leaving thousands of families displaced. By contrast, according to Peace Now, Israeli authorities began construction on more than 23,696 housing units between 2009 and 2020 in Israeli settlements in Area C. Transfer of an occupying power’s civilian population to an occupied territory violates the Fourth Geneva Convention.

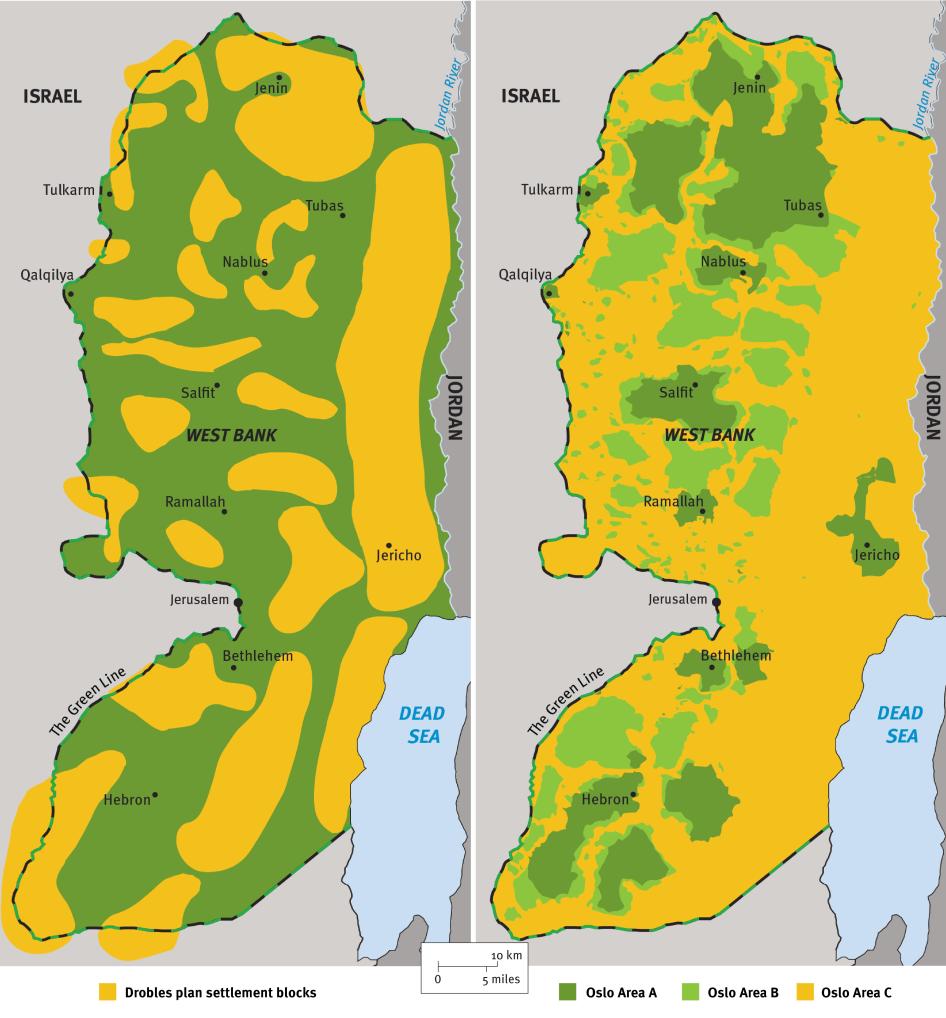

These policies grow out of longstanding Israeli government plans. For example, the 1980 Drobles Plan, which guided the government’s settlement policy in the West Bank at the time and built on prior plans, called for authorities to “settle the land between the [Arab] minority population centers and their surroundings,” noting that doing so would make it “hard for Palestinians to create territorial contiguity and political unity” and “remove any trace of doubt about our intention to control Judea and Samaria forever.”

In Jerusalem, the government’s plan for the municipality, including both the west and occupied east of the city, sets the goal of “maintaining a solid Jewish majority in the city” and a target demographic “ratio of 70% Jews and 30% Arabs”—later adjusted to a 60:40 ratio after authorities acknowledged that “this goal is not attainable” in light of “the demographic trend.”

The Israeli government has also carried out discriminatory seizures of land inside Israel. Authorities have seized through different mechanisms at least 4.5 million dunams of land from Palestinians, according to historians, constituting 65 to 75 percent of all land owned by Palestinians before 1948 and 40 to 60 percent of the land that belonged to Palestinians who remained after 1948 and became citizens of Israel. Authorities in the early years of the state declared land belonging to displaced Palestinians as “absentee property” or “closed military zones,” then took it over, converted it to state land, and built Jewish communities there. Authorities continue to block Palestinian citizen landowners from accessing land that was confiscated from them. A 2003 government-commissioned report found that “the expropriation activities were clearly and explicitly harnessed to the interests of the Jewish majority” and that state lands, which constitute 93 percent of all land in Israel, effectively serve the objective of “Jewish settlement.” Since 1948, the government has authorized the creation of more than 900 “Jewish localities” in Israel, but it has allowed only a handful of government-planned townships and villages for Palestinians, created largely to concentrate previously displaced Bedouin communities living in the Negev.

Land confiscations and other discriminatory land policies in Israel hem in Palestinian municipalities inside Israel, denying them opportunities for natural expansion enjoyed by Jewish municipalities. The vast majority of Palestinian citizens, who make up around 19 percent of the Israeli population, live in these municipalities, which have an estimated jurisdiction over less than 3 percent of all land in Israel. While Palestinians in Israel can move freely, and some live in “mixed cities,” such as Haifa, Tel Aviv-Jaffa, and Acre, Israeli law permits small towns to exclude prospective residents based on their asserted incompatibility with the town’s “social-cultural fabric.” According to a study by a professor at Technion-Israel Institute of Technology in Haifa, there are more than 900 small Jewish towns, including kibbutzim, across Israel that can restrict who lives there. None of them have any Palestinians living among them.

In the Negev in Israel, Israeli authorities have refused to legally recognize 35 Palestinian Bedouin communities, making it impossible for their 90,000 or so residents to live lawfully in the communities they have lived in for decades. Instead, authorities have sought to concentrate Bedouin communities in larger recognized townships in order, as expressed in governmental plans and statements by officials, to maximize the land available for Jewish communities. Israeli law considers all buildings in these unrecognized villages to be illegal, and authorities have refused to connect most to the national electricity or water grids or to provide even basic infrastructure such as paved roads or sewage systems. The communities do not appear on official maps, most have no educational facilities, and residents live under constant threat of having their homes demolished. Israeli authorities demolished more than 10,000 Bedouin homes in the Negev between 2013 and 2019, according to government data. They razed one unrecognized village that challenged the expropriation of its lands, al-Araqib, 185 times.

Authorities have implemented these policies pursuant to government plans since the early years of the state that called for restricting Bedouin communities in order to secure land suitable for settling Jews. Several months before becoming prime minister in December 2000, Ariel Sharon declared that Bedouins in the Negev “are gnawing at the country’s land reserves,” which he described as “a demographic phenomenon.” As prime minister, Sharon went on to pursue a multi-billion-dollar plan that transparently sought to boost the Jewish population in the Negev and Galilee regions of Israel, areas that have significant Palestinian populations. His deputy prime minister, Shimon Peres, later described the plan as a “battle for the future for the Jewish people.”

Sharon’s push to Judaize the Negev, as well as the Galilee, developed against the backdrop of the government’s decision to withdraw Jewish settlers from Gaza. After ending Jewish settlement there, Israel began to treat Gaza effectively as a territorial jurisdiction whose population it could consider as outside the demographic calculus of Jews and Palestinians who live in Israel and in the vast majority of the OPT—the West Bank including East Jerusalem—that Israel intends to retain. Israeli officials at the time acknowledged the demographic objectives behind the move. Amid the push to withdraw settlers from Gaza, Sharon said in an August 2005 address to Israelis, “Gaza cannot be held onto forever. Over one million Palestinians live there and they double their numbers with every generation.” Peres said the same month, “We are disengaging from Gaza because of demography.”

Despite withdrawing its settlers and ground troops, Israel has remained in critical ways the supreme power in Gaza, dominating through other means and hence maintaining its legal obligations as an occupying power, as the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) and the United Nations (UN), among others, have determined. Most significantly, Israel bans Palestinians living there (with only narrow exceptions) from leaving through the Erez Passenger Crossing it controls and instituted a formal “policy of separation” between Gaza and the West Bank, despite Israel having recognized within the framework of the Oslo Accords these two parts of the OPT as collectively forming a “single territorial unit.” The generalized travel ban, which has remained in place since 2007 and reduced travel out of Gaza to a fraction of what it was two decades ago, is not based on an individualized security assessment and fails any reasonable test of balancing security concerns against the right to freedom of movement for over two million people.

Authorities have also sharply restricted the entry and exit of goods to and from Gaza, which, alongside Egypt often shutting its border, effectively seals it off from the outside world. These restrictions have contributed to limiting access to basic services, devastating the economy, and making 80 percent of the population reliant on humanitarian aid. Families in Gaza in recent years have had to make do without centrally provided electricity for between 12 and 20 hours per day, depending on the period. Water is also critically scarce; the UN considers more than 96 percent of the water supply in Gaza “unfit for human consumption.”

Within the West Bank as well, Israeli authorities prohibit Palestinian ID holders from entering areas such as East Jerusalem, lands beyond the separation barrier, and areas controlled by settlements and the army, unless they secure difficult-to-obtain permits. They have also erected nearly 600 permanent obstacles, many between Palestinian communities, that disrupt daily life for Palestinians. In sharp contrast, Israeli authorities allow Jewish settlers in the West Bank to move freely within the majority of the West Bank under its exclusive control, as well as to and from Israel, on roads built to facilitate their commutes and integrate them into every facet of Israeli life.

Demographic considerations factor centrally in Israel’s separation policy between Gaza and the West Bank. In particular, in the rare cases when they allow movement between the two parts of the OPT, Israeli authorities permit it predominantly in the direction of Gaza, thereby facilitating population flow away from the area where Israel actively promotes Jewish settlement. The Israeli army’s official policy states that while a West Bank resident can apply “for permanent resettlement in the Gaza Strip for any purpose that is considered humanitarian (usually family reunification),” Gaza residents can settle in the West Bank only “in the rarest cases,” usually related to family reunification. In these cases, authorities are mandated to aim to resettle the couple in Gaza. Official data shows that Israel did not approve a single Gaza resident to resettle in the West Bank, outside of a handful who filed Supreme Court petitions between 2009 and March 2017, while permitting several dozen West Bank residents to relocate to Gaza on the condition that they sign a pledge not to return to the West Bank.

Beyond the closure policy, Israeli authorities have often used oppressive and indiscriminate means during hostilities and protests in Gaza. Since 2008, the Israeli army has launched three large-scale military offensives in Gaza in the context of hostilities with armed Palestinian groups. As described in the report, those offensives have included apparently deliberate attacks on civilians and civilian infrastructure and killed well over 2,000 civilians. In addition, Israeli forces have regularly fired on Palestinian demonstrators and others who have approached fences separating Gaza and Israel in circumstances when they did not pose an imminent threat to life, killing 214 demonstrators in 2018 and 2019 alone and maiming thousands. These practices stem from a decades-long pattern of using excessive and vastly disproportionate force to quell protests and disturbances, at great cost to civilians. Despite the frequency of such incidents over the years, Israeli authorities have failed to develop law enforcement tactics that comport with international human rights norms.

Discriminatory Restrictions on Residency and Nationality

Palestinians face discriminatory restrictions on their rights to residency and nationality to varying degrees in the OPT and Israel. Israeli authorities have used their control over the population registry in the West Bank and Gaza—the list of Palestinians they consider lawful residents for purposes of issuing legal status and identity cards—to deny residency to hundreds of thousands of Palestinians. Israeli authorities refused to register at least 270,000 Palestinians who were outside the West Bank and Gaza when the occupation began in 1967 and revoked the residency of nearly 250,000, mostly for being abroad for too long between 1967 and 1994. Since 2000, Israeli authorities have largely refused to process family reunification applications or requests for address changes by Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza. The freeze effectively bars Palestinians from acquiring legal status for spouses or relatives not already registered and makes illegal, according to the Israeli army, the presence in the West Bank of thousands of Gaza residents who arrived on temporary permits and now live there, since they effectively cannot change their address to one in the West Bank. These restrictions have the effect of limiting the Palestinian population in the West Bank.

Authorities regularly deny entry into the West Bank to non-registered Palestinians who had lived in the West Bank but left temporarily (to study, work, marry, or for other reasons) and to their non-registered spouses and other family members.

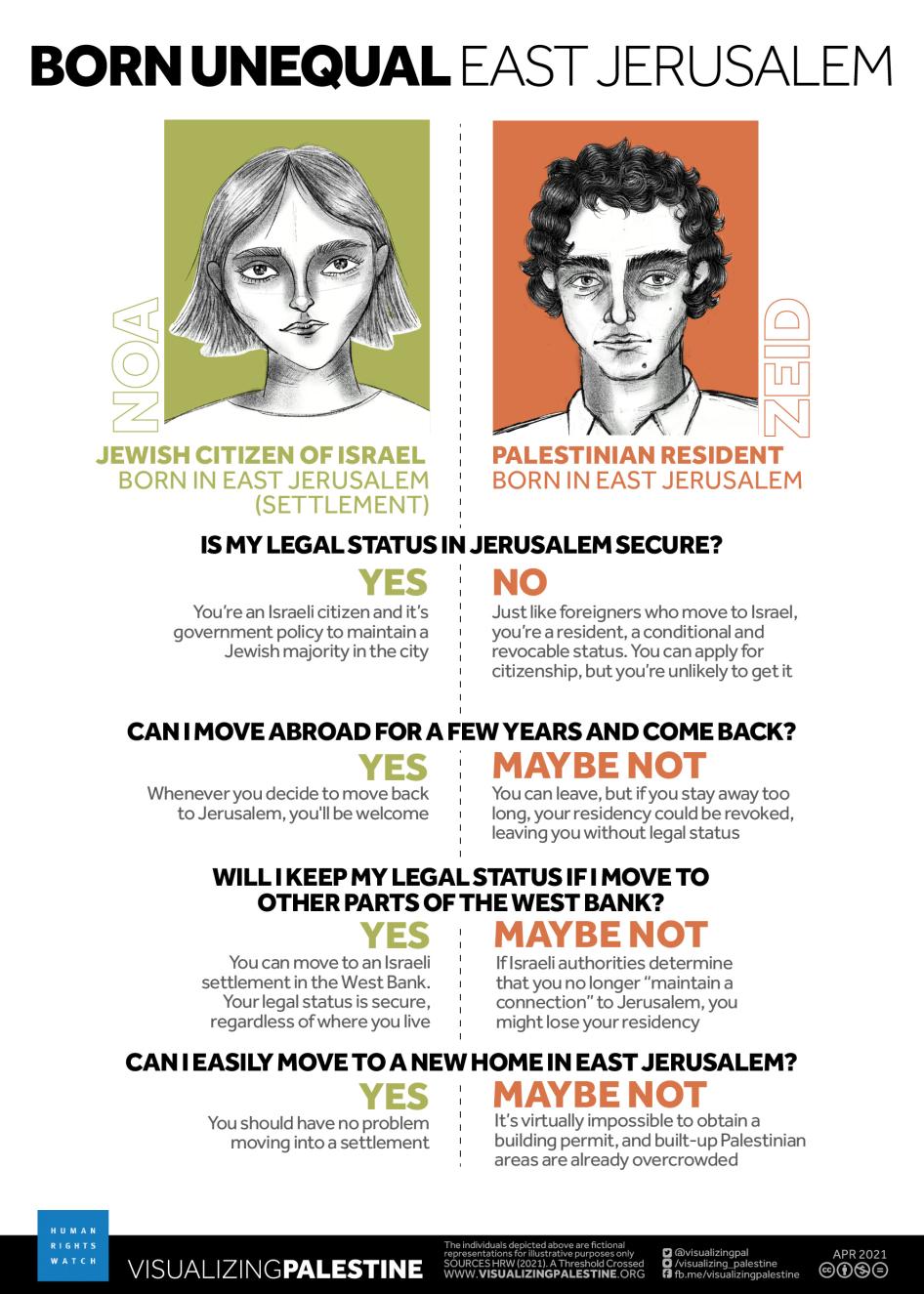

When Israel annexed East Jerusalem in 1967, it applied its 1952 Law of Entry to Palestinians who lived there and designated them as “permanent residents,” the same status afforded to a non-Jewish foreigner who moves to Israel. The Interior Ministry has revoked this status from at least 14,701 Palestinians since 1967, mostly for failing to prove a “center of life” in the city. A path to Israeli citizenship exists, but few apply and most who did in recent years were not granted citizenship. By contrast, Jewish Israelis in Jerusalem, including settlers in East Jerusalem, are citizens who do not have to prove connections to the city to maintain their status.

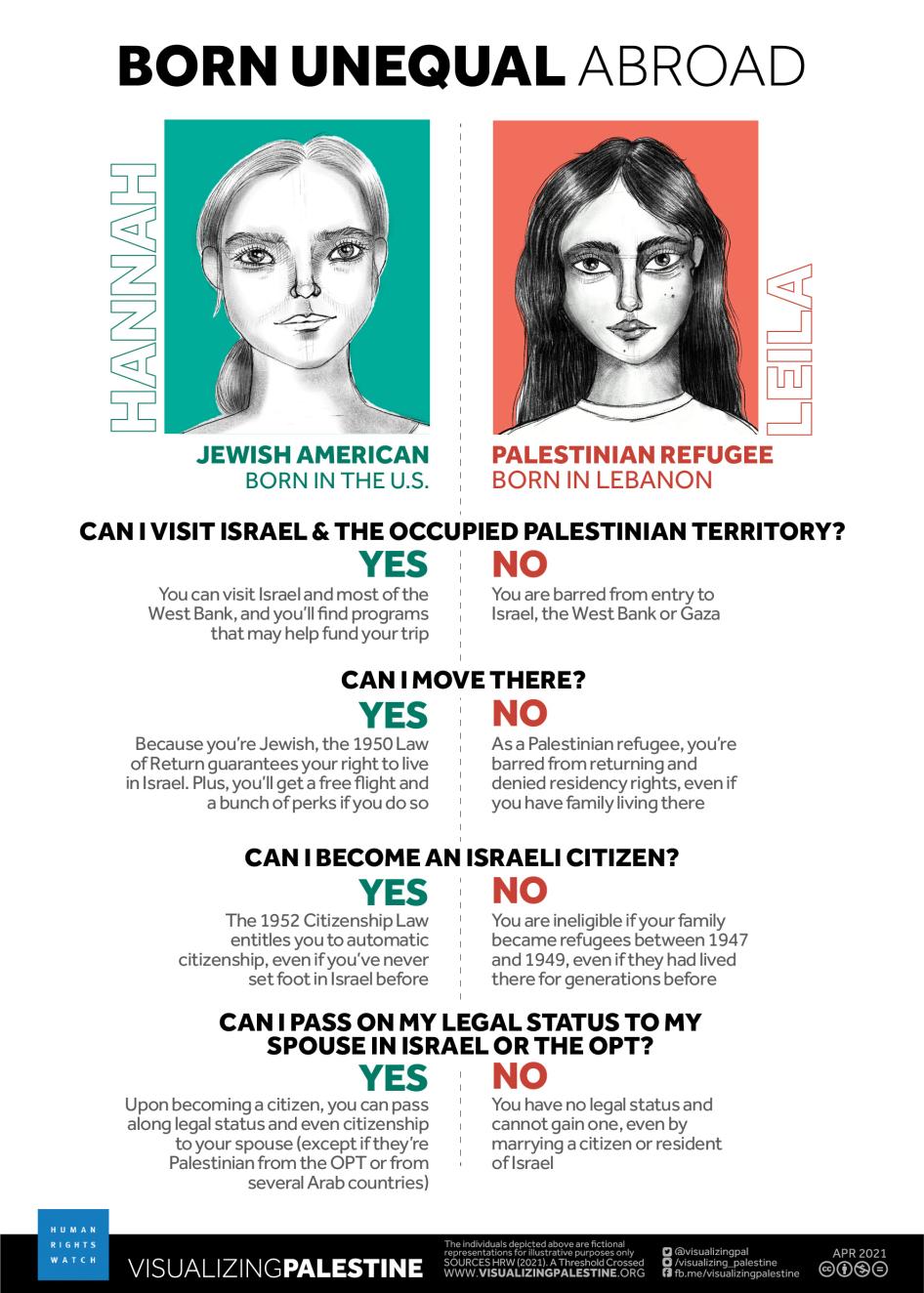

Inside Israel, Israel’s Proclamation of Independence affirms the “complete equality” of all residents, but a two-track citizenship structure contradicts that vow and effectively regards Jews and Palestinians separately and unequally. Israel’s 1952 Citizenship Law contains a separate track exclusively for Jews to obtain automatic citizenship. That law grows out of the 1950 Law of Return which guarantees Jewish citizens of other countries the right to settle in Israel. By contrast, the track for Palestinians conditions citizenship on proving residency before 1948 in the territory that became Israel, inclusion in the population registry as of 1952, and a continuous presence in Israel or legal entry in the period between 1948 and 1952. Authorities have used this language to deny residency rights to the more than 700,000 Palestinians who fled or were expelled in 1948 and their descendants, who today number more than 5.7 million. This law creates a reality where a Jewish citizen of any other country who has never been to Israel can move there and automatically gain citizenship, while a Palestinian expelled from his home and languishing for more than 70 years in a refugee camp in a nearby country, cannot.

The 1952 Citizenship Law also authorizes granting citizenship based on naturalization. However, in 2003, the Knesset passed the Citizenship and Entry into Israel Law (Temporary Order), which bars granting Israeli citizenship or long-term legal status to Palestinians from the West Bank and Gaza who marry Israeli citizens or residents. With few exceptions, this law, renewed every year since and upheld by the Israeli Supreme Court, denies both Jewish and Palestinian citizens and residents of Israel who choose to marry Palestinians the right to live with their partner in Israel. This restriction, based solely on the spouse’s identity as a Palestinian from the West Bank or Gaza, notably does not apply when Israelis marry non-Jewish spouses of most other foreign nationalities. They can receive immediate status and, after several years, apply for citizenship.

Commenting on a 2005 renewal of the law, the prime minister at the time, Ariel Sharon, said: “There’s no need to hide behind security arguments. There’s a need for the existence of a Jewish state.” Benjamin Netanyahu, who was then the finance minister, said during discussions at the time: “Instead of making it easier for Palestinians who want to get citizenship, we should make the process much more difficult, in order to guarantee Israel’s security and a Jewish majority in Israel.” In March 2019, this time as prime minister, Netanyahu declared, “Israel is not a state of all its citizens,” but rather “the nation-state of the Jewish people and only them.”

International human rights law gives broad latitude to governments in setting their immigration policies. There is nothing in international law to bar Israel from promoting Jewish immigration. Jewish Israelis, many of whom historically migrated to Mandatory Palestine or later to Israel to escape anti-Semitic persecution in different parts of the world, are entitled to protection of their safety and fundamental rights. However, that latitude does not give a state the prerogative to discriminate against people who already live in that country, including with respect to rights concerning family reunification, and against people who have a right to return to the country. Palestinians are also entitled to protection of their safety and fundamental rights.

Israeli Justifications of Policies and Practices

Israeli authorities justify many of the policies documented in this report as responses to Palestinian anti-Israeli violence. Many policies, though, like the denial of building permits in Area C, East Jerusalem, and the Negev in Israel, residency revocations for Jerusalemites, or expropriation of privately owned land and discriminatory allocation of state lands, have no legitimate security justification. Others, including the Citizenship and Entry into Israel Law and freeze of the OPT population registry, use security as a pretext to advance demographic objectives.

Israeli authorities do face legitimate security challenges in Israel and the OPT. However, restrictions that do not seek to balance human rights such as freedom of movement against legitimate security concerns by, for example, conducting individualized security assessments rather than barring the entire population of Gaza from leaving with only rare exceptions, go far beyond what international law permits. Even where security forms part of the motivation behind a particular policy, that does not give Israel a carte blanche to violate human rights en masse. Legitimate security concerns can be present among policies that amount to apartheid, just as they can be present in a policy that sanctions the use of excessive force or torture.

Officials sometimes claim that measures taken in the OPT are temporary and would be rescinded in the context of a peace agreement. From former Prime Minister Levi Eshkol, of the Labor Party, declaring in July 1967 that “I see only a quasi-independent region [for Palestinians], because the security and land are in Israeli hands,” to Netanyahu of the Likud in July 2019 stating that “Israeli military and security forces will continue to rule the entire territory, up to the Jordan [River],” a range of officials have made clear their intent to maintain overriding control over the West Bank in perpetuity, regardless of what arrangements are in place to govern Palestinians. Their actions and policies further dispel the notion that Israeli authorities consider the occupation temporary, including the continuing of land confiscation, the building of the separation barrier in a way that accommodated anticipated growth of settlements, the seamless integration of the settlements’ sewage system, communication networks, electrical grids, water infrastructure and a matrix of roads with Israel proper, as well as a growing body of laws applicable to West Bank Israeli settlers but not Palestinians. The possibility that a future Israeli leader might forge a deal with Palestinians that dismantles the discriminatory system and ends systematic repression does not negate the intent of current officials to maintain the current system, nor the current reality of apartheid and persecution.

Recommendations

The Israeli government should dismantle all forms of systematic domination and oppression that privilege Jewish Israelis and systematically repress Palestinians, and end the persecution of Palestinians. In particular, authorities should end discriminatory policies and practices with regards to citizenship and residency rights, civil rights, freedom of movement, allocation of land and resources, access to water, electricity, and other services, and granting of building permits.

The findings that the crimes of apartheid and persecution are being committed do not deny the reality of Israeli occupation or erase Israel’s obligations under the law of occupation, any more than would a finding that other crimes against humanity or war crimes have been carried out. As such, Israeli authorities should cease building settlements and dismantle existing ones and otherwise provide Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza with full respect of their human rights, using as a benchmark the rights that it grants Israeli citizens, as well as the protections that international humanitarian law grants them.

The Palestinian Authority (PA) should end forms of security coordination with the Israeli army that contribute to facilitating the crimes against humanity of apartheid and persecution.

The finding of crimes against humanity should prompt the international community to reevaluate its approach to Israel and Palestine. The US, which for decades has largely failed to press the Israeli government to end its systematic repression of Palestinians, has in some instances in recent years signaled its support for serious abuses such as the building of settlements in the occupied West Bank. Many European and other states have built close ties with Israel, while supporting the “peace process,” building the capacity of the PA, and distancing themselves from and sometimes criticizing specific abusive Israeli practices in the OPT. This approach, which overlooks the deeply entrenched nature of Israeli discrimination and repression of Palestinians there, minimizes serious human rights abuses by treating them as temporary symptoms of the occupation that the “peace process” will soon cure. It has enabled states to resist the sort of accountability that a situation of this gravity warrants, allowing apartheid to metastasize and consolidate. After 54 years, states should stop assessing the situation through the prism of what might happen should the languishing peace process one day be revived and focus instead on the longstanding reality on the ground that shows no signs of abating.

Crimes against humanity can serve as the basis for individual criminal liability in international fora, as well as in domestic courts outside of Israel and the OPT under the principle of universal jurisdiction.

In light of the decades-long failure by Israeli authorities to rein in serious abuses, the International Criminal Court’s Office of the Prosecutor should investigate and prosecute individuals credibly implicated in the crimes against humanity of apartheid or persecution. The ICC has jurisdiction over, and the prosecutor has opened an investigation into, serious crimes committed in the OPT. In addition, all governments should investigate and prosecute those credibly implicated in these crimes, under the principle of universal jurisdiction and in accordance with national laws.

Beyond criminality, Human Rights Watch calls on states to establish through the UN an international commission of inquiry to investigate systematic discrimination and repression based on group identity in the OPT and Israel. The inquiry should be mandated to establish and analyze the facts; identify those responsible for serious crimes, including apartheid and persecution, with a view to ensuring that the perpetrators are held accountable; as well as collect and preserve evidence related to abuses for future use by credible judicial institutions.

States should also establish through the UN a position of UN global envoy for the crimes of persecution and apartheid with a mandate to mobilize international action to end persecution and apartheid worldwide.

States should issue statements expressing concern about Israel’s practice of apartheid and persecution. They should vet agreements, cooperation schemes, and all forms of trade and dealing with Israel to screen for those directly contributing to the commission of the crimes of apartheid and persecution against Palestinians, mitigate the human rights impacts, and, where not possible, end the activities and funding found to facilitate these serious crimes.

The implications of the findings of this report for businesses are complex and beyond the scope of this report. At a minimum, businesses should cease activities that directly contribute to the commission of the crimes of apartheid and persecution. Companies should assess whether their goods or services contribute to the commission of the crimes of apartheid and persecution, such as equipment used in the unlawful demolition of Palestinian homes, and cease providing goods and services that will likely be used for such purposes, in accordance with the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights.

States should impose individual sanctions, including travel bans and asset freezes, against officials and individuals responsible for the continued commission of these serious crimes and condition arms sales and military and security assistance to Israel on Israeli authorities taking concrete and verifiable steps towards ending their commission of the crimes of apartheid and persecution.

The international community has for too long explained away and turned a blind eye to the increasingly transparent reality on the ground. Every day a person is born in Gaza into an open-air prison, in the West Bank without civil rights, in Israel with an inferior status by law, and in neighboring countries effectively condemned to lifelong refugee status, like their parents and grandparents before them, solely because they are Palestinian and not Jewish. A future rooted in the freedom, equality, and dignity of all people living in Israel and the OPT will remain elusive so long as Israel’s abusive practices against Palestinians persist.

Methodology

This report focuses on Israel’s treatment of Palestinians in the Occupied Palestinian Territory (OPT) and in Israel. It is not a comprehensive examination of all repressive policies, practices, and other facets of institutional discrimination. It also does not account for all human rights abuses in these areas, including rights abuses committed by Palestinian authorities or armed groups, which Human Rights Watch has covered extensively elsewhere.[4] Rather, it examines discriminatory policies, laws, and regulations that privilege Jewish Israelis to the detriment of Palestinians.

While the report evaluates whether specific Israeli policies and practices amount to the crimes against humanity of apartheid and persecution, it does not delve into the potential criminal liability of particular Israeli officials.

This report is based primarily on years of documentation carried out by Human Rights Watch, as well as by Israeli, Palestinian, and international human rights groups. Human Rights Watch also reviewed Israeli laws, government planning documents, statements by officials, land records, and legal standards governing the crimes of apartheid and persecution. The report includes several case studies, based on 40 interviews with affected persons, current and former officials, lawyers, and NGO representatives, as well as on-site visits, all conducted by Human Rights Watch in 2019 and 2020. Some interviews took place at locations in the OPT and Israel, but, in part due to movement restrictions imposed during the COVID-19 pandemic, many were conducted by phone.

Human Rights Watch conducted most of the interviews that are included in this report individually, in Arabic or English. We conducted them with the consent of those being interviewed and told each of the interviewees how Human Rights Watch would use the information provided.

Human Rights Watch is withholding names of some interviewees for their security, giving them instead pseudonyms, which are noted at first mention between quotation marks.

Human Rights Watch also wrote to Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu on July 20, 2020, soliciting the government’s perspectives generally on the issues covered. A copy of the letter is included in the appendix of this report. The Prime Minister’s Office confirmed receipt by phone on August 6 and by email on August 12, but, as of publication, had not responded.

I. Background

More than 700,000 Palestinians fled or were expelled from their homes and more than 400 Palestinian villages were destroyed in events around the establishment of the Israeli state in 1948.[5] Between 1949 and 1966, Israeli authorities placed most of the Palestinians who remained within the borders of the new state under military rule, confining them to dozens of enclaves, requiring them to obtain permits to leave their enclaves, and severely restricting their rights.[6]

In June 1967, Israel seized control of the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, from Jordan and the Gaza Strip from Egypt, which make up the Occupied Palestinian Territory (OPT), as well as the Golan Heights from Syria, and the Sinai Peninsula from Egypt, following an armed conflict known as the Six-Day War.

Israeli authorities have since retained control over the OPT. In the occupied West Bank, the Israeli army has militarily ruled over Palestinians living there, except in East Jerusalem, which Israel unilaterally annexed in 1967. Annexation does not change East Jerusalem’s status as occupied territory under international law. Throughout the West Bank, Israel has facilitated the building of Israeli-only settlements. The Fourth Geneva Convention, which applies to military occupations, prohibits the transfer of an occupying power’s civilian population to an occupied territory.[7] In the occupied Gaza Strip, Israel withdrew its ground troops in 2005, but continues to exert substantial control through other means.

Israel also unilaterally annexed the Golan Heights in 1981, though it also remains an occupied territory under international law. Israel ended its occupation of the Sinai Peninsula as a result of the 1978 Camp David Accords with Egypt.

In 1993 and 1995, the Israeli government and the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) signed the Oslo Accords, which created the Palestinian Authority (PA) to manage some Palestinian affairs in parts of the OPT for a transitional period, not exceeding five years, until the parties forged a permanent status agreement.[8] The Oslo Accords, supplemented by later agreements, divided the West Bank largely into three distinct regions: Area A, where the PA would manage full security and civil affairs, Area B, where the PA would manage civil affairs and Israel would have security control, and Area C, under the exclusive control of Israel. Area A largely incorporates the major Palestinian city centers, Area B the majority of towns and many villages, and Area C the remaining 60 percent of the West Bank.[9] The Oslo Accords, though, did not end the occupation in any part of the OPT.

The parties did not reach a final status agreement by 2000 and have not in the two decades since, despite off and on negotiations primarily mediated by the US. The West Bank remains primarily divided between Areas A, B, and C, with Israel retaining overall principal control and the PA managing some affairs in Areas A and B. In Gaza, Hamas has effectively governed since seizing control in June 2007 following months of clashes between the Palestinian political parties Fatah and Hamas and more than a year of political uncertainty after Hamas won a plurality of seats in PA elections.[10] In January 2020, the Trump Administration presented its “Peace to Prosperity” plan, which envisions permanent Israeli domination over the entire territory and formal annexation of settlements, the Jordan Valley, and other parts of Area C.[11] It also calls for a Palestinian state, but sets conditions that make its realization nearly impossible.

The decades-long “peace process” has neither significantly improved the human rights situation on the ground nor altered the reality of overall Israeli control across Israel and the OPT. Instead, the peace process is regularly cited to oppose efforts for rights-based international action or accountability,[12] and as cover for Israel’s entrenched discriminatory rule over Palestinians in the OPT.[13]

In recent years, Israeli officials have vowed to unilaterally annex additional parts of the West Bank,[14] and the coalition agreement that led to the formation of an Israeli government in May 2020 established a process to bring annexation for governmental approval.[15] In August, Prime Minister Netanyahu said that Israel would delay the move following an agreement with the United Arab Emirates, but noted that “there is no change to my plan to extend sovereignty” over the West Bank.[16] Annexation would not change the reality of Israeli occupation or the protections due to Palestinians as an occupied population under international humanitarian law.

Although the mechanics and intensity of the abuses differ between the OPT and Israel, the same power, the government of the state of Israel, has primary control across both. That authority governs all Jewish Israelis in Israel and the OPT under a single body of laws (Israeli civil law) and, to ensure their domination, structurally discriminates against Palestinians and represses them to varying degrees across different areas on issues such as security of legal status and access to land and resources, as the report documents. Across Israel and the OPT, Israel grants Jewish Israelis privileges denied to Palestinians and deprives Palestinians of fundamental rights on account of their being Palestinian.

While the role of different Israeli state entities varies in different parts of the OPT—with the army, for example, primarily administering the West Bank and exerting control from outside the territory in Gaza, whereas the same civil authorities that govern in Israel also rule over East Jerusalem—they all operate under the direction of the Israeli government headed by the prime minister. Every Israeli government since 1967 has pursued or maintained abusive policies in the OPT. In the West Bank, at least ten government ministries directly fund projects to serve settlements, and a Settlement Affairs Ministry was formed in May 2020.[17] The Knesset has also passed laws and formed committees that apply exclusively there.[18] The Israeli Supreme Court serves as the court of last resort for Israeli actions in both Israel and the OPT and has ruled on major cases that have determined policies in both territories.[19] Quasi-state bodies, such as the World Zionist Organization (WZO) and the Jewish National Fund (JNF), have also supported activities in both the OPT and Israel.[20]

II. The Crimes Against Humanity of Apartheid and Persecution

The prohibition of crimes against humanity is among the most fundamental in international criminal law. The concept, which dates back more than one hundred years and became clearly part of international criminal law in the 1945 Charter of the International Military Tribunal that created the court that prosecuted members of the leadership of Nazi Germany in Nuremberg, refers to a small number of the most serious crimes under international law.[21]

The 1998 Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, which came into force in 2002, sets out 11 crimes that can amount to a crime against humanity when “committed as part of a widespread or systematic attack directed against any civilian population, with knowledge of the attack.”[22] The statute defines “attack” as a “course of action involving the multiple commission of acts… pursuant to or in furtherance of a State or organizational policy.” “Widespread” refers to the scale of the acts or number of victims,[23] whereas “systematic” indicates a “pattern or methodological plan.”[24] Crimes against humanity can be committed during peace or armed conflict.

The Explanatory Memorandum of the Rome Statute explains that crimes against humanity “are particularly odious offenses in that they constitute a serious attack on human dignity or grave humiliation or a degradation of one or more human beings. They are not isolated or sporadic events but are part either of a government policy (although the perpetrators need not identify themselves with this policy) or of a wide practice of atrocities tolerated or condoned by a government or a de facto authority.”[25]

Among the 11 distinct crimes against humanity are the crimes of apartheid and persecution. There is no hierarchy among crimes against humanity; they are of the same gravity and lead to the same consequences under the Rome Statute.

The State of Palestine acceded to the Rome Statute in 2015.[26] It filed a declaration that gives the International Criminal Court jurisdiction over crimes in the Rome Statute, including the crimes against humanity of apartheid and persecution that are alleged to have been committed in the OPT since June 13, 2014.[27]

Apartheid

General Prohibition

Apartheid, a term originally coined in relation to specific practices in South Africa, has developed over the past half-century into a universal legal term incorporated in international treaties, numerous UN resolutions, and the domestic law of many countries to refer to a particularly severe system of institutional discrimination and systematic oppression.[28] Apartheid is prohibited as a matter of customary international law.[29]

According to the International Law Commission (ILC), the prohibition against apartheid represents a peremptory norm of international law.[30] The ILC describes apartheid as “a serious breach on a widespread scale of an international obligation of essential importance for safeguarding the human being,” noting its prohibition in a range of legal instruments within states and “general agreement among Governments as to the peremptory character” of the prohibition.[31] The International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD), which has 182 states parties,[32] including Israel and Palestine, declares that “States Parties particularly condemn racial segregation and apartheid and undertake to prevent, prohibit and eradicate all practices of this nature in territories under their jurisdiction.”[33]

International Criminal Law

Beyond its mere prohibition, apartheid has also been recognized as a crime against humanity for more than 50 years. The 1968 Convention on the Non-Applicability of Statutory Limitations to War Crimes declared that crimes against humanity included “inhuman acts resulting from the policy of apartheid.”[34]

In 1973, the UN General Assembly adopted a specific convention on apartheid, the Convention on the Suppression and Punishment of the Crime of Apartheid (“Apartheid Convention”), declaring it to constitute a crime against humanity.[35] The Apartheid Convention, which came into force in 1976 and has 109 states parties, including the state of Palestine but not Israel, states:

The term “the crime of apartheid”, which shall include similar policies and practices of racial segregation and discrimination as practiced in southern Africa, shall apply to the following inhuman acts committed for the purpose of establishing and maintaining domination by one racial group of persons over any other racial group of persons and systematically oppressing them…[36]

The Apartheid Convention then identifies a number of “inhuman acts” that, when committed for the purpose of domination and systematic oppression, make up the crime of apartheid, including:

(b) Deliberate imposition on a racial group or groups of living conditions calculated to cause its or their physical destruction in whole or in part;

(c) Any legislative measures and other measures calculated to prevent a racial group or groups from participation in the political, social, economic and cultural life of the country and the deliberate creation of conditions preventing the full development of such a group or groups, in particular by denying to members of a racial group or groups basic human rights and freedoms, including the right to work, the right to form recognised trade unions, the right to education, the right to leave and to return to their country, the right to a nationality, the right to freedom of movement and residence, the right to freedom of opinion and expression, and the right to freedom of peaceful assembly and association;

(d) Any measures including legislative measures, designed to divide the population along racial lines by the creation of separate reserves and ghettos for the members of a racial group or groups, the prohibition of mixed marriages among members of various racial groups, the expropriation of landed property belonging to a racial group or groups or to members thereof.[37]

The 1977 Additional Protocol I to the Geneva Conventions, with 174 states parties, identifies “practices of apartheid and other inhuman and degrading practices involving outrages upon personal dignity, based on racial discrimination” as a grave breach of the treaty.[38]

The Rome Statute of 1998, which has 123 states parties, identifies apartheid as a crime against humanity, defining it as:

Inhumane acts of a character similar to those referred to in paragraph 1, committed in the context of an institutionalized regime of systematic oppression and domination by one racial group over any other racial group or groups and committed with the intention of maintaining that regime.[39]

In setting out what constitutes inhumane acts, the statute lists a series of crimes against humanity, including “deportation or forcible transfer,” “persecution,” and “other inhumane acts of a similar character intentionally causing great suffering, or serious injury to body or to mental or physical health.”[40] To amount to apartheid, these acts must take place in the context of an institutionalized regime of systematic domination and oppression and committed with the intention of maintaining that regime.[41]

The International Law Commission also included the crime of apartheid in its draft proposed treaty on Crimes Against Humanity, incorporating the Rome Statute definition of the crime.[42]

Definition of Key Terms

No court has to date heard a case involving the crime of apartheid and therefore interpreted the meaning of the following terms as set out in the Apartheid Convention and Rome Statute definitions of the crime of apartheid:

Racial Group: Both the Apartheid Convention and Rome Statute use the term “racial group,” but neither defines it.[43] The development of the Apartheid Convention against the backdrop of events in southern Africa in the 1970s, as referenced in the text of the Convention, as well as the non-inclusion of other categories beyond race, and the rejection of proposals by some states to expand the treaty’s scope, could lead to a narrower interpretation focused on divisions based on skin color.[44] While discussion of the meaning of “racial group” during the drafting of the Rome Statute appears to have been minimal,[45] its inclusion in the definition of apartheid, after the end of apartheid in South Africa and when international human rights law had clearly defined racial discrimination to include differences of ethnicity, descent, and national origin, indicates that “racial group” within the Rome Statute reflects, and would likely be interpreted by courts to reflect, a broader conception of race.

The International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD), which was adopted in 1965 and came into legal force in 1969, defines “racial discrimination” as “any distinction, exclusion, restriction or preference based on race, colour, descent or national or ethnic origin which has the purpose or effect of nullifying or impairing the recognition, enjoyment or exercise, on an equal footing, of human rights and fundamental freedoms in the political, economic, social, cultural or any other field of public life.”[46] The Committee on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (CERD), the UN body charged with monitoring the implementation of the ICERD, has consistently found that members of racial and ethnic groups, as well as groups defined based on descent or their national origin, face racial discrimination.[47] Rather than treat race as constituting only genetic traits, Human Rights Watch uses this broader definition.

No international criminal case has ruled on the definition of “racial group” in the context of the crime against humanity of apartheid. But international criminal courts, in the context of more recent genocide cases, have addressed the meaning of “national, ethnical, racial or religious group” in the definition of that crime in part by evaluating group identity based on context and the construction of local actors, in particular the perpetrators, as opposed to earlier approaches that focused on hereditary physical traits. The International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) held that the assessment of whether a particular group may be considered as protected from the crime of genocide “will proceed on a case-by-case basis, taking into account both the evidence proffered and the political, social and cultural context.”[48] The International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) also found that determinations should be “made on a case-by-case basis, consulting both objective and subjective criteria.” The court, in particular, held that national, ethnic, racial or religious groups should be identified “by using as a criterion the stigmatisation of the group, notably by the perpetrators of the crime, on the basis of its perceived national, ethnical, racial or religious characteristics.”[49] The ICTY held in a 1999 case that “to attempt to define a national, ethnical or racial group today using objective and scientifically irreproachable criteria would be a perilous exercise.”[50]

An understanding of “racial group” in line with ICERD’s conception of “racial discrimination” and international criminal courts’ “subjective approach” to determining racial and other groups mirrors the evolution in how the social sciences understand race and gives coherence to the meaning of race across international law.[51]

Israeli law has also interpreted race broadly, not limiting it to skin color. The Israeli Penal Code defines racism, in the context of the crime of “incitement to racism,” as “persecution, humiliation, degradation, a display of enmity, hostility or violence, or causing violence against a public or parts of the population, all because of their color, racial affiliation or national ethnic origin.”[52] Under Article 7A of Israel’s Basic Law: The Knesset—1958, which bars candidates from running for office if they engage in “incitement,”[53] Israel’s Supreme Court has barred candidates, such as from the Jewish Power (Otzma Yehudit) party, from running for office based on vitriolic comments made about Palestinians.[54]

While it is beyond the scope of this report to analyze the group identities of Jewish Israelis or Palestinians, it is clear that in the local context, Jewish Israelis and Palestinians are regarded as separate identity groups that fall within the broad understanding of “racial group” under international human rights law. The 1950 Law of Return, which guarantees Jews the right to immigrate to Israel and gain citizenship, defines “Jew” to include “a person who was born of a Jewish mother,” embracing a descent-based, as opposed to a purely religious, classification.[55] Many in Israel characterize the virulently anti-Palestinian positions of the Jewish Power party, and before that the Kach Party, as “racist.”[56] Prominent Israelis also labeled as “racist” or “race-baiting” a warning that Netanyahu issued to his supporters on election day 2015 that “Arab voters are coming out in droves to the polls.”[57]

Meanwhile, on account of their identity, Palestinians face discrimination and repression, as this report makes clear. Palestinians have deep cultural, political, economic, social, and family ties across Israel, the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and the Gaza Strip. For much of the modern era, Palestinians moved freely across these areas, which constituted mandatory Palestine, under British administration, in the post-World War I era. The Palestine Liberation Organization Charter defines Palestinians as “those Arab nationals who, until 1947, normally resided in Palestine,” emphasizing that the identity is “transmitted from parents to children.”[58] Even within Israel where both Jews and Palestinians are citizens, authorities classify Jews and Palestinians as belonging to different “nationalities.”[59]

CERD found in its latest review of Israel’s record under ICERD in December 2019 that Palestinians in Israel and the OPT constitute a minority group deserving of protection against “all policies and practices of racial segregation and apartheid” in comparison to Jewish communities.[60]

Institutionalized Regime: This term, incorporated into the Rome Statute but not the Apartheid Convention, appears to have originated in a proposal from the US delegation during the drafting to limit the application of the crime of apartheid to states and exclude non-state groups.[61] Alongside the term “systematic,” which appears in both the Apartheid Convention and Rome Statute, the term “regime” underscores the existence of formal organization and structure, and more than isolated discriminatory policies or acts.[62] The system can cover entire states or more limited geographic areas, depending on the allocation of power, unity of authority, or differing oppressive laws, policies, and institutions, among other factors.

Domination: This term, which lacks a clear definition in law, appears in context to refer to an intent by one group to maintain heightened control over another, which can involve control over key levers of political power, land, and resources. The reference is found in both the Rome Statute and Apartheid Convention.

The focus on domination, as opposed to formal sovereignty, also indicates that the crime of apartheid can be carried out by authorities outside its own territory and with respect to non-citizens.[63] A finding that authorities of one state have committed the crime of apartheid in an external territory would no more undermine the formal sovereignty the other state enjoys or detract from the factual reality of occupation than would a finding that other crimes against humanity or war crimes had been carried out there.[64]

Systematic Oppression: This term, also without a clear definition in law, appears to refer to the methods used to carry out an intent to maintain domination. The reference in the Apartheid Convention to “policies and practices of racial discrimination as practiced in southern Africa” indicates that oppression must reach a high degree of intensity to meet the requisite threshold for the crime .[65]

Persecution

The crime of persecution traces back to the 1945 International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg. The tribunal’s charter recognizes “persecutions on political, racial or religious grounds” as crimes against humanity.[66]

The Rome Statute also identifies persecution as a crime against humanity, defining it as “the intentional and severe deprivation of fundamental rights contrary to international law by reason of the identity of the group or collectivity.”[67] The statute broadened the scope of the crime to encompass “any identifiable group or collectivity on political, racial, national, ethnic, cultural, religious, gender as defined in paragraph 3, or other grounds that are universally recognized as impressible under international law.”[68] The statute limits the crime to applying only “in connection with” other crimes identified under it.[69] The customary international law definition of persecution, though, includes no such limitation.[70]

International criminal lawyer Antonio Cassese, who served as a judge in the leading ICTY case that examined persecution within international criminal law (Prosecutor v. Kupreskic), identified the crime against humanity of persecution as a crime under customary international law.[71] He defined persecution under customary international law as referring to acts that a) result in egregious or grave violations of fundamental human rights, b) are part of a widespread or systematic practice, and c) are committed with discriminatory intent.[72]

Neither the Rome Statute nor customary international law clearly set the threshold of what constitutes a violation that is sufficiently “severe” or “egregious.” Human Rights Watch recognizes that many human rights violations cause serious harm. However, for the determination of whether the crime against humanity of persecution has been committed, Human Rights Watch requires the most serious forms of violations before the requirements of “severe” or “egregious” can be met.

Legal Consequences of Finding Crimes Against Humanity

The commission of crimes against humanity can serve as the basis for individual criminal liability not only in the domestic courts of the perpetrator country but also in international courts and tribunals, as well as in domestic courts outside the country in question under the principle of universal jurisdiction. Individual criminal liability extends beyond those who carry out the acts to those who order, assist, facilitate, aid, and abet the offense. Under the principle of command responsibility, military, and civilian officials up to the top of the chain of command can be held criminally responsible for crimes committed by their subordinates when they knew or should have known that such crimes were being committed but failed to take reasonable measures to prevent the crimes or punish those responsible.

In December 2019, ICC Prosecutor Fatou Bensouda concluded a nearly five-year preliminary inquiry into the Palestine situation and determined that “all the statutory criteria” to proceed with a formal investigation of alleged serious crimes by Israelis and Palestinians had been met. The prosecutor found a “reasonable basis” to believe that war crimes had been committed by Israeli and Palestinian authorities but did not reference any crimes against humanity.[73] Although the prosecutor did not require formal judicial authorization to move forward with a formal investigation, she nonetheless sought a ruling from the court’s judges on the ICC’s territorial jurisdiction before proceeding.[74]

In February 2021, the court ruled that it had jurisdiction over crimes committed in the OPT, including East Jerusalem, confirming Palestine’s status as a state party to the Rome Statute able to confer that jurisdiction. [75] This jurisdiction would include the ability to prosecute the crimes against humanity of apartheid and persecution. In March 2021, the Office of the Prosecutor announced the opening of a formal investigation into the situation in Palestine.[76]

Israel signed the Rome Statute in 2000, but did not ratify it and said in August 2002 that it did not intend to do so.[77] However, the ICC has jurisdiction to investigate and prosecute any person, including those of Israeli nationality, where there is evidence that they are criminally responsible for the commission of the crimes against humanity of persecution or apartheid within any state that has ratified the Rome Statute, where the relevant criteria are met. That includes Palestine, allowing for the prosecution of crimes that Israeli nationals commit in the OPT.

The Apartheid Convention also calls on states parties to prosecute those who commit the crime and over whom they have jurisdiction, as well as to take other measures aimed at “prevention, suppression and punishment” of the crime of apartheid.[78]

Israeli law criminalizes crimes against humanity, including persecution but not apartheid, only in the context of crimes committed in Nazi Germany.[79] Palestinian law does not criminalize crimes against humanity.

III. Intent to Maintain Domination

Israeli government policy has long sought to engineer and maintain a Jewish majority in Israel and maximize Jewish Israeli control over land in Israel and the OPT. Laws, planning documents, and statements by officials demonstrate that the pursuit of domination by Jewish Israelis over Palestinians, in particular over demographics and land, guides government policy, and actions to this day.

This chapter will show that this objective amounts to an intent to maintain domination by one group over another. When inhumane acts are carried out in the context of systematic oppression pursuant to that intent to maintain domination, the crime against humanity of apartheid is committed.

Discriminatory intent, when it gives rise to severe abuses of fundamental rights, also makes up the crime against humanity of persecution.

To analyze the motivations behind Israeli policies towards Palestinians today, which developed over many years with much of the architecture established in the early years of the state and the occupation, this chapter considers materials that in some cases date back decades. This does not implicate every official cited in seeking to dominate Palestinians. In fact, some Israeli officials and parties advocated positions that, if implemented, could have avoided such policies.

Israeli authorities justify some of these policies in the name of security, but, as this chapter shows, they often use security as a justification to advance demographic objectives. In other cases, officials advocate for policies to safeguard Israel’s identity as a Jewish state. Israel can, like any other state, seek to promote a particular identity, but that does not include a license to violate fundamental rights. Not all policies designed to promote Judaization constitute rights abuses. Particular policies can, though, provide evidence of a discriminatory intent or purpose to maintain domination by Jewish Israelis.