Imran Khan’s Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf party won the highest number of seats in parliamentary elections in July, and Khan took office as prime minister in August. It was the second consecutive constitutional transfer of power from one civilian government to another in Pakistan. In the campaign, Khan pledged to make economic development and social justice a priority.

Attacks by Islamist militants resulted in fewer deaths in Pakistan in 2018 than in recent years. However, strikes primarily targeting law enforcement officials and religious minorities killed hundreds of people. The Taliban and other armed militants killed and injured hundreds of people in a failed effort to disrupt the elections.

The government continues to muzzle dissenting voices in nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and media on the pretext of national security. Militants and interest groups also threaten freedom of expression through threats and violence.

Women, religious minorities, and transgender people face violent attacks, discrimination, and government persecution, with authorities failing to provide adequate protection or hold perpetrators accountable.

Freedom of Expression and Attacks on Civil Society

A climate of fear continues to impede media coverage of abuses both by government security forces and militant groups. Journalists increasingly practiced self-censorship in 2018, after threats and attacks from militant groups. Media outlets came under pressure from authorities to avoid reporting on several issues, including criticism of government institutions and the judiciary. In several cases, government regulatory agencies blocked cable operators from broadcasting networks that had aired critical programs.

Gul Bukhari, a journalist in Lahore, was abducted in June by unknown assailants and released after a few hours. On the same night, Asad Kharal, a broadcast journalist, was assaulted and injured in Lahore.

Kadafi Zaman, a Norwegian journalist, was arrested by police in July while covering a political rally and was beaten up. Zaman was released after three days.

Human Rights Watch received several credible reports of intimidation, harassment, and surveillance of various NGOs by government authorities in 2018. The government used its “Regulation of INGOs in Pakistan” policy to impede the registration and functioning of international humanitarian and human rights groups.

Freedom of Religion and Belief

At least 17 people remain on death row in Pakistan after being convicted under the draconian blasphemy law, and hundreds await trial. Most of those facing blasphemy allegations are members of religious minorities.

In October, Pakistan’s Supreme Court quashed the conviction and ordered the release of 47-year-old Aasia Bibi, a Christian woman from a village in Punjab province who had been on death row for eight years. Groups supporting the blasphemy law took to the streets to protest the decision of Aasia’s release, damaged public and private property, and threatened judges of the Supreme Court, government officials, and military leadership with violent reprisals.

Blasphemy allegations and related rhetoric from both private actors and officials increased in 2018. However, the government did not amend the law and instead encouraged discriminatory prosecutions and other abuses against vulnerable groups.

In February, Patras Masih, 18, and Sajid Masih, 24, were charged with blasphemy in Lahore. Sajid Masih alleged that the police torture he endured while being held led him to attempt suicide, by jumping out of the interrogation room window. He was badly injured but survived.

In May, then-Interior Minister Ahsan Iqbal was shot in an assassination attempt by an individual affiliated with an anti-blasphemy group at an election rally in Narowal district, Punjab.

In May, a mob led by anti-blasphemy clerics attacked and destroyed two historic Ahmadiyya religious buildings.

Members of the Ahmadiyya religious community continue to be a major target for prosecutions under blasphemy laws, as well as specific anti-Ahmadi laws across Pakistan. They face increasing social discrimination as militant groups and the Islamist political party Tehreek-e-Labbaik (TLP) accuse them of “posing as Muslims.” The Pakistan penal code continues to treat “posing as Muslims” by Ahamdis as a criminal offense. They were effectively excluded from participating in the 2018 parliamentary elections: to vote, Ahmadis are required to declare they are not Muslims, which many see as a renunciation of their faith.

In September, the new Imran Khan government appointed Atif Mian, a prominent academic belonging to the Ahmadiyya community, to join the government as economic adviser and then, almost immediately after, asked him to step down after the TLP and other Islamist groups objected to his appointment because of his religion. Atif Mian said he stepped down because of “adverse pressure regarding my appointment from the mullahs and their supporters.”

Women’s and Children’s Rights

Violence against women and girls—including rape, so-called honor killings, acid attacks, domestic violence, and forced marriage—remains a serious problem. Pakistani activists estimate that there are about 1,000 “honor” killings every year.

In June, the murder of 19-year-old Mahwish Arshad in Faisalabad district, Punjab, for refusing a marriage proposal gained national attention. According to media reports, at least 66 women were murdered in Faisalabad district in the first six months of 2018, the majority in the name of “honor.”

Justice Tahira Safdar was appointed as the chief justice of Balochistan High Court, becoming the first woman ever appointed chief justice of a high court in Pakistan.

Women from religious minority communities remain particularly vulnerable to abuse. A report by the Movement for Solidarity and Peace in Pakistan found that at least 1,000 girls belonging to Christian and Hindu communities are forced to marry Muslim men every year. The government has done little to stop such forced marriages.

Early marriage remains a serious problem, with 21 percent of girls in Pakistan marrying before the age of 18, and 3 percent marrying before age 15.

The Taliban and affiliated armed groups continued to attack schools and use children in suicide bombings in 2018. In August, militants attacked and burned down at least 12 schools in Diamer district of Pakistan’s Gilgit-Baltistan region. At least half were girls’ schools. Pakistan has not banned the use of schools for military purposes, or endorsed the Safe Schools Declaration as recommended by the United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights in 2017.

Over 5 million primary school-age children in Pakistan are out of school, most of them girls. Human Rights Watch research found girls miss school for reasons including, lack of schools, costs associated with studying, child marriage, harmful child labor, and gender discrimination.

Child sexual abuse remains disturbingly common in Pakistan with 141 cases reported in just Lahore, Punjab, in the first six months of 2018. At least 77 girls and 79 boys were raped or sexually assaulted in the first half of 2018, according to police reports, but none of the suspects had been convicted at time of writing and all had been released on bail.

In January, the rape and murder of 7-year-old Zainab Ansari in Kasur, Punjab, led to nationwide outrage and prompted the government to promise action. On June 12, the Supreme Court upheld the convictions of Imran Ali for the rape and murder of Zainab Ansari and at least eight other girls. Imran Ali was executed on October 17. On August 8, the body of a 5-year-old girl who was raped and murdered was found in Mardan district, Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa. The rape of a 6-year-old girl in Sukkur district, Sindh, was confirmed by a medical report on August 10.

According to the organization Sahil, an average of 11 cases of child sexual abuse are reported daily across Pakistan. Zainab Ansari was among the dozen children to be murdered in Kasur district, Punjab in 2018. In 2015, police identified a gang of child sex abusers in the same district.

Terrorism, Counterterrorism, and Law Enforcement Abuses

Suicide bombings, armed attacks, and killings by the Taliban, Al-Qaeda, and their affiliates targeted religious minorities, security personnel, and politicians, resulting in hundreds of deaths.

Taliban and other militant groups targeted candidates and their supporters in the lead-up to the July election. On July 13, in one of the most deadly suicide bombings in Pakistan’s history, at least 128 people were killed during an election rally held by the Balochistan Awami Party (BAP) in Mastung district, Balochistan. BAP politician Nawabzada Siraj Raisani was killed in the attack. A faction of the Taliban claimed responsibility, media reported. The same day, four people were killed and at least 32 injured, when the convoy of Akram Khan Durrani, a senior political leader of Muttahida Majlis-e-Amal (MMA), was targeted in a remote-controlled blast in Bannu district, Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa. Durrani survived.

On July 10, Haroon Bilour, a senior leader of the Awami National Party (ANP), was killed along with at least 20 others in a suicide bombing targeting his election meeting in Peshawar, Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa. The militant group Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) claimed responsibility for the attack.

On election day on July 25, 31 people were killed in a suicide attack targeting a polling station in Quetta. The militant group Islamic State (ISIS) claimed responsibility for the attack.

On November 23, gunmen attacked the Chinese consulate in Karachi, killing four people, including two police officers. The militant group Baloch Liberation Army claimed responsibility for the attack. On the same day, a suicide attack claimed by ISIS in Orakzai tribal district killed at least 33 people.

During counterterrorism operations, Pakistani security forces often are responsible for serious human rights violations including torture, enforced disappearances, detention without charge, and extrajudicial killings, according to Pakistan human rights defenders and defense lawyers. Counterterrorism laws also continue to be misused as an instrument of political coercion. Authorities do not allow independent monitoring of trials in military courts and many defendants are denied the right to a fair trial.

Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity

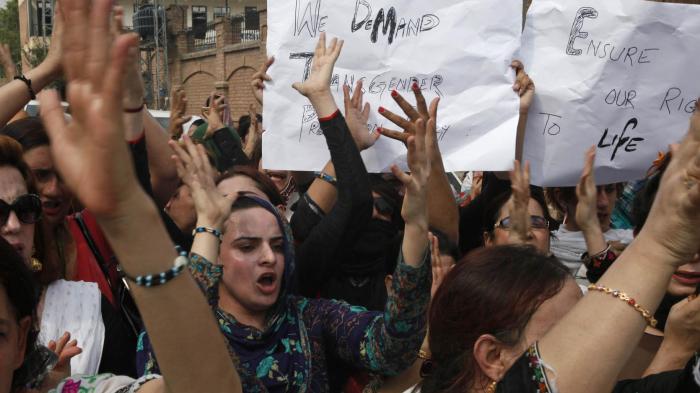

Violence against transgender and intersex women in Pakistan continues.

According to the local group Trans Action, 479 attacks against transgender women were reported in Khyber-Pakhunkhwa province in 2018. At least four transgender women were killed there in 2018, and at least 57 have been killed there since 2015. On May 4, the fatal shooting of Muni, a transgender woman in Mansehra district, Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa province, attracted national attention.

In a major development, Pakistan's parliament in May, passed a law guaranteeing basic rights for transgender citizens and outlawing discrimination by employers. The law grants individuals the right to self-identify as male, female, or a blend of genders, and to have that identity registered on all official documents, including National Identification Cards, passports, driver's licenses, and education certificates.

Pakistan’s penal code criminalizes same-sex sexual conduct, placing men who have sex with men and transgender women at risk of police abuse, and other violence and discrimination.

Death Penalty

Pakistan has more than 8,000 prisoners on death row, one of the world’s largest populations facing execution. Pakistani law mandates capital punishment for 28 offenses, including murder, rape, treason, certain acts of terrorism, and blasphemy. Those on death row are often from the most marginalized sections of society.

In April, the Pakistan Supreme Court suspended the execution of Imdad Ali and Kaniz Fatima, prisoners with psychosocial disabilities and ordered a bench of the Supreme Court to examine the issue. The court said that a person with psychosocial disabilities cannot be executed. Imdad Ali and Kaniz Fatima, however, remained on death row at time of writing.

Key International Actors

In March, the UN Human Rights Council (HRC) adopted the outcome of Pakistan’s third Universal Periodic Review (UPR), which was conducted in November 2017. The Pakistani government rejected a large number of key recommendations that states made to it during the UPR.

Since Pakistan was elected to the Human Rights Council in 2017, it has generally failed to take a strong stance on serious human rights situations. However, in September 2017, it led Organisation for Islamic Cooperation member states at the council in expressing concerns about the ethnic cleansing campaign against the Rohingya by the Myanmar military.

Pakistan’s volatile relationship with United States, the country’s largest development and military donor, deteriorated in 2018, amid signs of mistrust. In August, the US stopped payment of US$300 million in military reimbursements to Pakistan for not taking adequate action against the Haqqani network, a Taliban-affiliated group that is accused of planning and carrying out attacks on civilians, government officials, and NATO forces in Afghanistan.

In June, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) released the first-ever report by the United Nations on human rights in Kashmir. The report noted that human rights abuses in Pakistani Kashmir were of a “different caliber or magnitude” to those in Indian Kashmir and included misuse of anti-terrorism laws to target dissent, and restrictions on the rights to freedom of expression and opinion, peaceful assembly, and association.

In July, the EU deployed an election observation mission to Pakistan that later issued a report highlighting significant curtailment of freedom of expression, allegations of interference in the electoral process by the military-led establishment, and politicization of the judiciary.

Pakistan and China deepened extensive economic and political ties in 2018, and work continued on the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, a project consisting of construction of roads, railways, and energy pipelines.

Historically tense relations between Pakistan and India have shown no signs of improvement, with both countries accusing each other of facilitating unrest and militancy.