The British government’s indefinite detention of foreign terrorism suspects has undermined human rights protections in Britain and impeded the development of an effective counterterrorism strategy, Human Rights Watch said in a briefing paper released today.

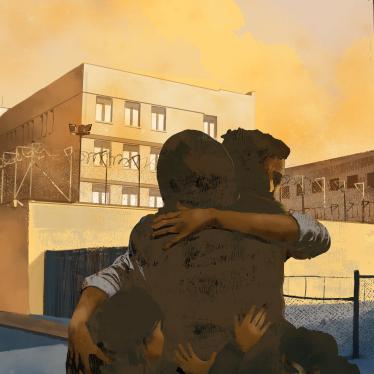

A dozen men are currently indefinitely detained without trial in maximum security facilities under the Anti-Terrorism Crime and Security Act, which the British Parliament passed in the wake of the September 11 attacks in the United States. Eight have been in detention since December 2001. None of the men have been charged with a crime. They have no expectation of release.

The briefing paper details how indefinite detention has seriously damaged the mental and physical health of the detainees. At the same time, it has harmed race and community relations and undermined the willingness of Muslims in the United Kingdom to cooperate with the police and security services. The policy has also impeded the development of a counterterrorism strategy that effectively addresses the full range of threats faced by the United Kingdom.

“Britain’s indefinite detention regime fails every test,” said Rachel Denber, acting executive director of Human Rights Watch’s Europe and Central Asia division. “It violates fundamental human rights, and it’s not clear it has made Britain a safer place.”

Indefinite detention without trial is a serious breach of international human rights law. In order to introduce the measure, the British government had to declare a state of emergency, which allowed it to derogate—or suspend—key human rights protections. The United Kingdom was the only country in Europe to suspend fundamental human rights obligations in the wake of September 11. The measures do not apply to British citizens who are suspected of terrorism.

In December, a group of senior British parliamentarians called for the urgent repeal of the indefinite detention regime. The regime has been criticized as discriminatory and unwarranted by the Parliament’s human rights committee, and by expert bodies in the United Nations and Council of Europe. A special nine-judge panel of the House of Lords is scheduled to hear an appeal on the lawfulness of indefinite detention in October.

The British government has signaled that it is considering deporting detainees to third countries by relying on “framework agreements.” In these agreements, more commonly known as “diplomatic assurances,” the government of the receiving country assures the government carrying out the deportation, such as the United Kingdom, that the detainees will not face torture or ill-treatment if returned.

“Diplomatic assurances have proved to be an ineffective safeguard in the past, and they do not shield Britain from its obligation not to expose people to such torture,” said Denber.