When Kosovo declared independence in February 2008, there was optimism that after almost a decade of drift, greater self-government and a newly energized international presence led by the EU might finally move it in the right direction.

Two years on, there is not much to celebrate. Despite its new authority, the government in Pristina tends either to gloss over Kosovo's human rights failings or to blame international agencies for the problems. The rule of law remains weak, despite some efforts by the EU police and justice mission. And the overall picture for Kosovo's already vulnerable Roma, Ashkali and Egyptian minorities seems to be getting worse, not better.

After a slow start (complicated by wrangling with member states, Serbia and the UN alike) the EU police and justice mission (EULEX) has made some positive steps, including setting up a mechanism to review any allegations of human rights abuse against it. EULEX has also sent some encouraging signals on accountability for war crimes, an issue on which Kosovo lags years behind other parts of the Balkans. It opened an investigation, for example, into the fate of 400 missing people, mostly Serbs, who were allegedly transferred in 1999 to detention facilities in Albania by the rebel Kosovo Liberation Army.

But the rule of law remains weak. The government in Pristina continues to dismiss the alleged 1999 transfers rather than investigating them. There has been little progress in bringing to justice those most responsible for anti-minority riots in 2004, a litmus test for the justice system. And the lack of a war crimes strategy has hampered efforts to identify the highest-priority cases among the hundreds of files the EU inherited from the UN.

Lack of clarity about Kosovo's status has hindered progress in the justice system. The issue of witness relocation is a case in point. It is widely acknowledged that fears of reprisals make witnesses reluctant to testify. In crimes involving attacks on minorities, political violence or organized crime in particular, often the only way to guarantee witness security is to relocate witnesses and their families outside the region.

Given the EU's objectives in Kosovo, relocating witnesses would seem like an obvious area for joint action, especially since individual member states are reluctant to volunteer. Yet the lack of consensus among member states about Kosovo's status has frustrated a common approach, undermining efforts to deliver justice for the most serious crimes.

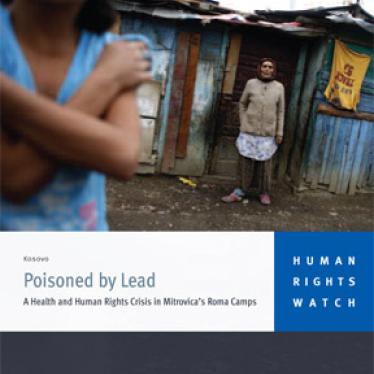

Given that Roma, Ashkali and Egyptians were consistently ignored during the status process, it is perhaps no surprise that Kosovo's self rule has brought them few benefits. Ten years after the destruction of the Roma quarter in Mitrovica, its former inhabitants remained displaced in camps in north Mitrovica exposed to ongoing and harmful lead contamination. Recent moves by the European Commission and US to find a durable solution to this symbol of failure to respect the rights of Roma in Kosovo are a hopeful sign and will be watched closely.

But most signs about treatment of Roma in Kosovo point to a deteriorating situation. A worrying series of attacks on Roma last summer drew a lacklustre response from the authorities and police. Despite a comprehensive government plan, little has actually been done to tackle the persistent discrimination and deprivation experienced by Roma. Many remain displaced inside and outside of Kosovo.

Their situation has not been helped by growing numbers of forced returns from Western Europe. In the absence of assistance, these returns place a further burden on Kosovo's already overstretched Roma communities. Little wonder then that the Council of Europe's Human Rights Commissioner renewed his call last week for a moratorium on returns.

It is not too late for Kosovo. With support from the European Union, real progress on rights and the rule of law is possible. But it will require a greater commitment from Brussels and Pristina to pursue the most serious crimes, greater expectations of the authorities from the EU on rights and justice, and a commitment to carry out the strategy to ameliorate the plight of Roma.

Benjamin Ward, deputy director of the Europe and Central Asia Division at Human Rights Watch, oversees research on the Western Balkans.