(Amsterdam) - Both the government of the Democratic Republic of Congo and the United Nations peacekeeping mission there should give greater emphasis to the protection of the nearly two million people displaced from their homes in the conflict-ridden eastern part of the country, Human Rights Watch said in a report released today. The UN Refugee Agency and international donors should ensure that assistance programs are not used to press them to go home before they are confident it is safe, Human Rights Watch said.

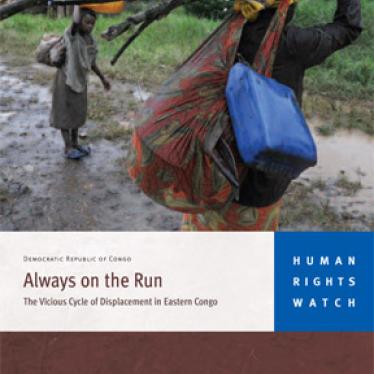

The 88-page report, "Always on the Run: The Vicious Cycle of Displacement in Eastern Congo," documents abuses against the displaced by all warring parties in all phases of displacement - during the attacks that uproot them; after they have been displaced and are living in the forests, with host families, or in camps; and after they or the authorities decide it is time for them to return home. The report is based on interviews with 146 people displaced from their homes in eastern Congo, as well as government officials, humanitarian workers, and journalists.

"Despite the government's stabilization and reconstruction efforts in eastern Congo, the population remains at risk from continuing violence," said Gerry Simpson, senior refugee researcher at Human Rights Watch and author of the report. "The internally displaced are among the most vulnerable people in the region, and they desperately need greater protection and assistance."

The report documents how myriad armed groups and the Congolese armed forces have displaced hundreds of thousands of people in North and South Kivu - eastern Congo's most volatile provinces - often multiple times and for many years. Combatants have forced civilians from their homes and lands, looted their properties, and punished them for suspected collaboration with enemy groups. These internally displaced persons (IDPs) have fled killings, rape, burning, pillaging, and forced labor.

According to UN estimates, the conflict has left at least 1.8 million civilians displaced -the fourth-largest internal displacement in the world - 1.4 million of them in North and South Kivu, bordering Rwanda. The situation remains fluid. While the UN estimates that 1 million internally displaced returned to their homes in 2009, at least 1.2 million people were forced to flee their homes during three successive military operations that began in January 2009. During the first three months of 2010, at least 115,000 people fled their homes due to continued military operations and danger in the Kivus.

The Vicious Cycle of Displacement

Abandoning possessions, homes, land, and livelihoods, large numbers of civilians first seek refuge in the forest near their villages in the hope of staying close to their fields and property. Many face further abuses there, including attacks by armed groups, rape, and robbery or are forced by the lack of shelter and hunger to seek refuge and help elsewhere.

At least 80 percent of eastern Congo's displaced find relative safety living with "host families," who themselves struggle to make ends meet. These displaced people face economic hardship, hunger, and disease, and the vast majority have little or no access to health care and education. With time, the host families become overburdened by the displaced, who are often then forced to move again.

Although many say they prefer to survive by cultivating land, their limited or non-existent access to fields means that many rely on humanitarian agencies. But for logistical or security reasons, these agencies are often unable to reach them in the places where they have taken refuge.

"Again and again, parents desperate to feed their children said that the absence of aid meant that they had no choice but to risk life and limb and return to places of grave danger," Simpson said. "They need aid both to fend off hunger and to avoid losing their lives at the hands of armed groups."

The Question of Return

Although military operations have continued throughout this year, Congolese government officials have repeatedly said that the security situation in eastern Congo has vastly improved and that it wants to see the displaced return home.

The report describes the obstacles displaced people face in returning to their homes: the general lack of security in villages away from main roads; abuses and threats by combatants on all sides of the conflict; accusations of collaborating with enemy groups; looting of harvests; extortion by ill-disciplined combatants; and disputes over land title, land occupation, and property destruction.

The report also documents how, at times, the authorities have let political considerations take priority over the needs of the displaced and have encouraged them to leave camps against their will. For example, in September 2009, Congolese authorities pressured 60,000 people in UN-run camps in and around Goma to return home.

Police and bandits raided and looted the camps as they were closing, attacking those who were slow to pack up and leave. A number of the displaced told Human Rights Watch they didn't even try to go home because they knew it was still unsafe, while others tried but were forced to disperse by armed groups. Neither the government nor UN agencies adequately monitored what happened to those 60,000 people.

"UN agencies and donors need to provide sufficient resources for emergency humanitarian assistance," Simpson said. "The displaced should be encouraged to return home only if it is safe and under voluntary and dignified conditions."

The Need for Protection

Congolese authorities have a poor track record in protecting displaced people and other civilians, with Congolese army units often abusing the population they are supposed to protect, Human Rights Watch said. Congolese authorities rely on almost 20,000 UN peacekeepers (the UN Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, MONUSCO) to help protect civilians under imminent threat of physical violence and assist displaced civilians who want to return home.

Human Rights Watch said that the UN mission has developed some innovative ways to enhance civilian protection, including a civilian protection strategy and Joint Protection Teams, who try to anticipate and respond to civilians' protection needs. These initiatives have had some positive impact, but the peacekeepers are spread across a vast and difficult terrain with overstretched resources, and their ability to protect civilians has also been limited. As a result, the challenge of protecting eastern Congo's civilians remains immense.

Protecting civilians, including people who are internally displaced, should remain the key consideration as the government develops post-conflict stabilization and reconstruction policies, Human Rights Watch said.

"The rebuilding of eastern Congo should not come at the expense of protection for its most vulnerable citizens," Simpson said. "The UN and donors should ensure that their rights to life and dignity remain central to any reconstruction efforts."